27 Sep The Rise, Fall and Rise of Tahoe’s Salmon

Celebrated for their colorful display during fall spawning season, kokanee continue to thrive in Lake Tahoe despite a history—and potential future—of ups and downs

Bears dine on spawning kokanee salmon in Taylor Creek on Tahoe’s South Shore, photo by Scott Sady

In their final days of life, Tahoe’s kokanee salmon put on a show. Flame red and hook-jawed, they thrash up Taylor Creek with an inescapable biological urge to spawn in the gravelly channel of the South Lake Tahoe stream where they were born. Between them and their final acts of procreation, a gauntlet of danger threatens. Insatiable bears, opportunistic coyotes, hovering osprey and hungry eagles all wait for a chance at an easy, and filling, fall meal.

The kokanee that complete the life cycle—from recently hatched fry in Taylor Creek to years in the depths of Tahoe, and back again to spawn at their birthplace—are destined to spend the last of their energy protecting their eggs, and die in a spectacular, genetically pre-programmed spectacle.

While this scene sounds like it belongs in the wilds of Alaska or the wilderness of Canada—not minutes from the casinos on Tahoe’s South Shore—there is good reason for this out-of-context salmon run.

A World War II-era fishery mishap brought this close relative of the sockeye salmon to the Jewel of the Sierra. Nearly a century later, eager anglers still ply the waters of Tahoe each summer, hooking the tasty, feisty, highly prized game fish that school dozens of feet below the surface.

These fish that were never supposed to be here have become an emblem of Lake Tahoe in the fall, finding their way into the hearts of everyone from schoolchildren to grizzled fishing guides. But their future is a question mark.

The salmon’s primary food source—a native plankton called daphnia—has dwindled dramatically over the decades since kokanee were introduced to Tahoe. And plantings of young kokanee in Taylor Creek, which regularly topped the list of kokanee plantings across the state for years, has not occurred since 2020.

Watching Kokanee salmon in the Taylor Creek Visitor Center stream profile chamber, photo by Scott Sady

Another challenge for Tahoe’s salmon is climate. Fall-spawning salmon adapted to life in a world where autumn streams still ran strong with ample water. Only an anomaly of dam-controlled water flowing from Fallen Leaf Lake to Lake Tahoe in the fall makes Taylor Creek a prime spawning stream. Otherwise, fall stream flows in Tahoe are incredibly fickle. One year they may be parched by drought. Another year, freak fall storms may flush the streams with fast-moving water that scour kokanee eggs from the gravel and eliminate an entire generation of salmon.

“Statewide I think that kokanee will struggle as we have longer drought cycles,” says Brant Allen, staff researcher with the UC Davis Tahoe Environmental Research Center.

But a curious thing is happening as the kokanee face these challenges. Ever adaptable, the same salmon that split off from their sockeye ancestors when they became landlocked are finding new food sources and new ways to spawn.

“This spring we saw schools of kokanee feeding on the surface, which is pretty unusual, and the word from the fishing guides is they were feeding on terrestrial insects,” says Allen. “Typically, the kokanee would be feeding on zooplankton at 30 to 100 feet deep.”

The same adaptability goes for their end-of-life spawning spectacle. Once concentrated at Taylor Creek because of state plantings at that site, the kokanee now are spreading out in the fall, finding any suitable habitat to send off the next generation of Tahoe salmon.

“They will spawn in various habitat,” says Allen. “Their preference would be to return to their native stream, but if they can’t reach that place, they will spawn in shoreline gravel or other tributaries.”

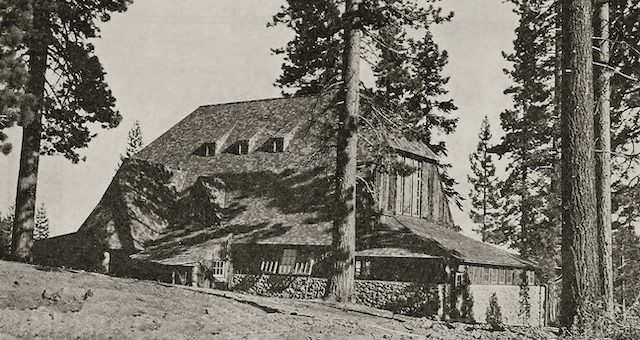

The Tahoe City fish hatchery designed by architect George McDougall, where in 1944 a tank overflowed and spilled kokanee fry into Lake Tahoe, courtesy photo

From Fishery Mishap to Fall Tradition

Tahoe City’s shingle- and bark-clad fish hatchery is a Tahoe landmark. Designed by architect George McDougall in 1919, it is where Nobel Prize–winning author John Steinbeck once famously worked. In 1944 a tank at the hatchery overflowed and spilled kokanee fry into Lake Tahoe. When the fish showed the ability to live and reproduce in the lake, the state began planting the salmon annually. Between 1940 and 1960 alone, 11.1 million kokanee fry were introduced to the lake, according to research conducted by renowned limnologist Charles Goldman, among others.

Plantings continued for decades, and the kokanee flourished even as the species’ complicated relationship with Tahoe’s native and non-native food web become more apparent. One of the keys to their survival was an anomaly—a dam-controlled stream on Tahoe’s South Shore that virtually guarantees flows even in the driest falls. Allen calls Taylor Creek’s water flows a “reverse hydrograph”—meaning the dam’s open gates in the late summer and fall result in water levels typically only seen in the spring in a region like Tahoe.

“By having a dam, they actually produce flows in the fall, so that supports fall-spawning fish, which tend to be non-native in the Sierra,” says Allen.

It’s here where kokanee, which are invisible to lake-goers for most of the year as they swim well below the surface, finally put on a show for an adoring public.

Spawning kokanee in a creek just north of Truckee, photo by Scott Thompson

Caught Between Native and Non-Native

The origin story of the kokanee salmon dates back 15,000 years, when a large ice cap melted across the Pacific Northwest. Sockeye salmon were the ocean-going members of this previously identical salmon family, living in river systems that connected to the sea. Sockeyes spawn in rivers, grow in fresh water and then spend years in the ocean before returning to their river to spawn. Kokanee are the landlocked version of the sockeye, spawning in rivers and gravelly lake shorelines and spending their lives in fresh water. Because of limits to food and habitat, kokanee grow significantly smaller than sockeye, but in other ways are nearly indistinguishable.

Kokanee are native to the Pacific Northwest, Canada and Alaska, but have been introduced widely across the United States as a game fish, including in California, Nevada, Oregon, Utah, Montana, Wyoming, Colorado and beyond.

Aside from Lake Tahoe, kokanee have also been introduced to other iconic alpine lakes. They were introduced to Crater Lake in Oregon and remain there to this day. Prior to 1888, it is believed that Crater Lake held no fish whatsoever. But William Gladstone Steel, who championed Crater Lake’s inclusion into the national park system, began introducing fish to its famously clear waters in 1888. Steel had a promotional and preservationist side to his personality. He was known as both the “father of Crater Lake” and “a one-man chamber of commerce” for ideas such as an elevator that would take visitors down to the lake’s surface, and for hosting climber conventions that ended with fireworks being shot from Wizard Island.

While it is believed that silver salmon were being planted in Crater Lake, kokanee must have been mixed in with the silver salmon fingerlings, as today only kokanee and rainbow trout inhabit North America’s deepest alpine lake.

Lake Tahoe has a similar history. Like the salmon in Crater Lake, Tahoe’s kokanee feast on the native plankton. Crater Lake’s kokanee have been observed feeding at the surface, a behavior that Tahoe’s kokanee are only recently adopting. And like Crater Lake, kokanee are only one of the non-native species to thrive in Lake Tahoe. They are positioned in the middle of an altered food web. Above them the mackinaw (also called lake trout) prey on kokanee in large numbers, using their toothy mouths to consume fish by the thousands. Meanwhile, kokanee consume daphnia, a native plankton that resembles a water flea. Daphnia populations crashed in Lake Tahoe in the 1960s and ’70s after the introduction of mysis shrimp, which were intended to serve as a food source for fish like kokanee.

However, the introduced shrimp dove deep into the lake during daylight hours, far below the reach of kokanee. In a twist of non-native species luck, mysis shrimp ended up being voracious predators of the native daphnia, the kokanee’s primary food source, while feeding the deeper-diving mackinaw—a double whammy that has led to the kokanee’s population fluctuations in Tahoe over time.

Captain Scott Carey, left, and first mate Scott Hoffman of Tahoe Sport Fishing show off a state record kokanee salmon caught near South Lake Tahoe in 2013. The fish measured 24.75 inches and weighed 5 pounds, 2 ounces, courtesy photo

The correlation between the daphnia and kokanee was driven home with a record-setting catch roughly a decade ago. Mature kokanee generally measure 12 to 14 inches in length. But in July 2013, a fisherman hooked into a 24.75-inch monster that weighed in at 5 pounds, 2 ounces, beating Tahoe’s previous record, caught in 1973, by 5 ounces.

Zach Gordon, a fishing guide and boat captain with Tahoe Sport Fishing, was on the boat that day. He says the crew knew the fish was unusual the moment they saw it.

“That was a mutant for sure,” Gordon says of the kokanee, which remains a California and Nevada state record.

Gordon and others have theorized that the behemoth kokanee skipped a year or two in its spawning cycle, making it older than other fish being caught.

But researchers tie a sudden surge in the daphnia population between 2011 and 2014 to the larger kokanee sizes during that period. For reasons unknown, the mysis shrimp had died off in Emerald Bay, and the daphnia returned in the shrimp’s absence.

“We saw daphnia come back in Emerald Bay and South Lake Tahoe, and they persisted for several years,” says Allen. “The kokanee that were able to prey on daphnia were just huge. Fish that size hadn’t been seen in 40 years. The reasons for that were the introduction of the mysis shrimp had eliminated the daphnia, which was the best food source for kokanee.”

While the mysis shrimp population recovered after 2014, their numbers have once again mysteriously declined in the past year, according to the 2022 “State of the Lake Report.” As a result, researchers expect daphnia—and the kokanee that dine on them—to flourish over the next one to four years.

Happy young kokanee anglers aboard a Tahoe Sport Fishing boat, courtesy photo

The Kokanee Catch

Lake Tahoe—as well as other waters in the region such as Donner Lake and Boca and Stampede reservoirs—has a reputation for great kokanee fishing. Like sockeye salmon, kokanee are prized for their bright red meat and rich flavor, while the fishing itself is action-packed and stunningly beautiful.

“This summer has been phenomenal,” says Gordon. “It started out a little later than usual. We didn’t really start fishing them really until July. It’s been gangbusters ever since.”

Gordon’s been guiding on Tahoe since 2005, and he says the kokanee fishery is so popular that it is not unusual to have 30 to 50 boats out fishing at the peak of kokanee season, which typically runs from mid-June to mid-October.

The allure is fast action—his clients will collectively haul in as many as 40 fish in an hour on a good day—but also the challenge for unguided parties.

“Tahoe is daunting if you are just coming up for the weekend,” says Gordon.

Part of the challenge is understanding the habits of the salmon, and mimicking their patterns of movement. Gordon says early in the season the fish often school on the West Shore of the lake, but then begin migrating toward South Lake Tahoe later in the season. And then there are the daily movements of the kokanee.

“They’ll often go out deep during the night and then come back in toward shore during the day. You just have to know how to follow them,” says Gordon.

Gordon has his hands in kokanee fishing in more ways than one. Apart from guiding on the lake, he owns Tahoe Trolling Company, a fishing lure business that makes flashers used for downriggers. He even runs lake ecology trips where he teaches children about Lake Tahoe’s aquatic species, all while continually tracking the same trends Allen observes in his UC Davis research.

To understand why kokanee, despite being non-native, have become so loved by so many Tahoe residents and visitors, you only have to think about a typical day in Gordon’s life.

He’s out on one of the most beautiful lakes on earth, chasing salmon as they swim deep below his boat’s hull, watching clients hook into hungry schools of fish.

And then there is one final up-close encounter with kokanee glory. Gordon will often take a kokanee fresh from the cold, clear water of Lake Tahoe and filet the rich, red meat into immaculate chunks of alpine sushi and serve it to his guests as they look out over the lake.

“Bright red, sashimi-grade sushi right on the boat,” he says.

David Bunker is a Truckee-based writer and editor.

No Comments