25 Sep Decades-Old Mountain Mystery Put to Rest

More than 50 years after legendary Tahoe ski racer Gardner Smith disappeared, his daughter would learn of his connection to a grizzly discovery high on Colorado’s Independence Pass

Only while skiing Sun Valley Resort’s Bald Mountain was Jeanne Smith Gaida able to feel the spirit of a man who had cast a long shadow on her life.

Around 2007, Gaida took a trip to the famed Idaho resort to meet with skiing raconteur Dick Dorworth and learn more about Gardner Smith, the father who had abandoned her and her mother decades prior.

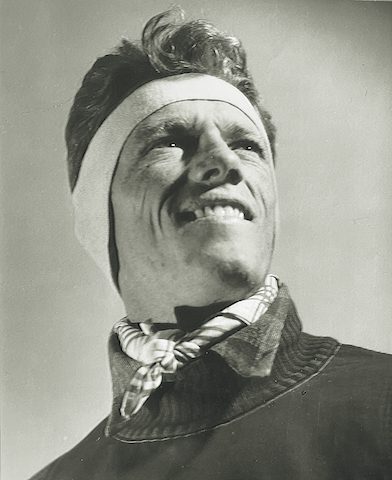

Smith was known as one of the top skiing talents in the Tahoe area in the 1950s, photo courtesy Jeanne Gaida

Smith was among the best ski racers in the Tahoe area in the 1950s and enlisted a style reminiscent of Norwegian ski legend Stein Eriksen. He displayed a persistent push to perfect his craft and had a mind sharp enough to prototype a now commonplace ski goggle design. Despite these abilities, he was never able to achieve lasting success and would struggle until ultimately meeting a tragic end.

But with Dorworth by her side telling the tales of Smith’s exploits among the world’s best skiers at Sun Valley’s 1956 Harriman Cup, Gaida could see her father—and his singular focus on skiing—with a new clarity. She could picture the knife-edged skills refined through hours of practice. She could glimpse the determination on her father’s face. She could trace his lines in the snow.

“It was like being there,” Gaida says of her time with Dorworth recounting Smith’s pursuit of excellence during the ski race, where Smith placed third.

It was the first time someone provided the details of her father’s passion for skiing with such enthusiasm and the first time she felt the excitement in her father’s life, Gaida says.

“It filled my cup. It filled my soul,” she says. “It gave me what I needed.”

After disappearing from Gaida’s and her mother’s lives shortly after Gaida’s birth in 1962, Smith eventually disappeared entirely, his whereabouts becoming a decades-long mystery that was only recently resolved with the help of forensic genealogy. And even with this recent discovery, much about this enigmatic figure from Tahoe’s skiing history, and his untimely demise, will likely never be known.

‘A Pioneer, an Explorer, a Man Ahead of His Time’

A longtime ski racer and former speed skiing world record holder who grew up on Tahoe’s South Shore, Dorworth was a friend of Smith’s and says he long admired him for his individuality and dedication. While Smith was often funny, clever and easygoing—“Whatever is right, friend,” he was known to say—Dorworth also notes a strain of anger at the world running through his personality.

Gardner Smith, photo courtesy Jeanne Gaida

“He was his own man, and he had a lot of conflict because he lived by his own standards,” Dorworth says.

A free spirit whose individuality, passion and ability to make people smile attracted friends, Smith also exhibited exacting ideals and a willingness to take stands—traits that didn’t always find universal acclaim, Dorworth wrote in a December 1983 article in Ski Magazine.

“Gardner’s resolution to explore and experiment with his own individuality gave him great personal strength, a trait treasured by his friends but maddening to his critics,” Dorworth wrote. “He was a maverick, a blessed and at the same time cursed man whose mind was drawn to the cutting edge; he was a pioneer, an explorer, a man ahead of (and therefore out of) his time, a natural foe of the status quo.”

This push to the fringes manifested in relatively simple adventures like riding his unicycle down the steps at Sugar Bowl Resort on Donner Summit to more daring exploits like fleeing Guatemala during the 1954 revolution after landing a plane there with friend and fellow Lake Tahoe wild man Dick Buek.

“In many ways they were soul mates, too,” Dorworth says of Smith and Buek. “They both were great skiers that in many ways never achieved their potential. Gardner just because of who he was and Dick because of his motorcycle wreck.”

Smith’s skiing and his influence on others probably never received the credit they deserved, but his passion for the sport was clearly central to his being.

“He was curious about what it meant to be a ‘human being’ and skiing was his avenue of discovery,” Dorworth wrote of Smith.

Life Without Gardner

Smith’s uncommon focus toward a life on snow took a very human toll on those around him. He met a British woman named Jennifer Dawn Andrews in Argentina in 1961, and the couple had Jeanne the following year. But Smith was never a part of his daughter’s life, abandoning his family shortly after Jeanne’s birth.

Smith pictured in 1952, photo courtesy Jeanne Gaida

Her mom, who grew up in Uruguay, struggled as a single parent in the 1960s and never really caught a break, Gaida says. Those around her hesitated to talk much about Smith, and a box of ski mementos only told a small part of the story.

“Growing up without a dad was sad,” Gaida says. “It was also just such an unusual story because he just kind of walked away.”

Smith’s parents, Paul and Bernita, introduced their family to skiing. Paul was credited with creating Boreal ski resort along Interstate 80 on Donner Summit. Gaida grew up between the San Francisco Bay Area and Modesto, with Paul and Bernita providing much to the baby girl who was left behind by their son. They were “everything” to her, Gaida says.

“My grandparents were always there. They were amazing,” she says.

Still, questions about her father persisted, and Gaida long wondered if one day he would show up.

“For me, it was just very hard. My whole life I never knew him,” Gaida says.

Now a Realtor in Austin, Texas, Gaida says that over time her story became an interesting one to discuss at parties—the ending of which she would need to rewrite earlier this year.

Whereabouts Unknown

By 1968, Gardner Smith’s ski racing career was gone, and he had taken to living on the road, according to Dorworth, who last saw him that year when he crashed on Dorworth’s couch. Smith had developed a “fascination with psychic phenomena and the latent powers of the mind,” had grown out of shape and had some of his friends questioning his mental state.

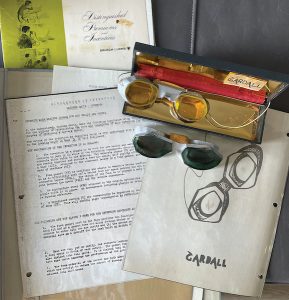

Double-lens ski goggles invented by Smith, photo courtesy Jeanne Gaida

“During the week he slept on my couch we had some fine conversations,” Dorworth wrote in the Ski Magazine article. “The clear intelligence and honest intensity I knew and admired as a boy were active and evident. Some folks thought Gardner had slipped over the line of sanity. Not me. He looked terrible, but there was nothing wrong with his mind that a healed heart, some rest and a little attentive encouragement wouldn’t cure.”

At the time, Smith was working on ski equipment designs, including ideas for ski grips and the now ubiquitous double lens ski goggles. He struggled to ask for help from friends, and what help Dorworth could provide ultimately wasn’t enough.

Family and friends subsequently lost contact with Smith and wondered for years about his whereabouts. Meanwhile, in Colorado, residents puzzled over the identity of a body found in the mountains near Aspen. Only recently would the seemingly separate mysteries be connected.

A Grizzly Discovery

On June 19, 1970, two men discovered the remains of a man about 2 miles from the 12,095-foot summit of Colorado’s Independence Pass. The decomposed body, which authorities concluded had been there since the previous winter, was partially covered with rocks and appeared to have been damaged by a snowplow. Strangely, an unworn sock was pulled over the left shoe, while the unidentified body was clothed in only a sweatshirt, khaki pants and multiple-layered socks. A razor and $7 were found in the pocket.

The body, which became known as the “Independence Pass John Doe,” was interred in Evergreen Cemetery in Leadville, Colorado, where it remained unidentified for more than 50 years. A caretaker of the cemetery took an interest in the grave and contacted the Colorado Bureau of Investigation, which led to the disinterment of the body for fingerprinting and DNA testing in 2013, according to the Leadville Herald Democrat.

But it wasn’t until recently, with advancements in genetic genealogy, that investigators were able to identify the body as that of Gardner Smith.

Gaida received the news in phone calls from a cousin and a forensic genealogy analyst from the Colorado Bureau of Investigation. Processing the emotions from the revelation took several months, Gaida says. It was made more difficult by the circumstances surrounding the discovery of Smith’s body pointing to such a bleak ending. To find out her father had been dead much of the time she was wondering if he would just show up also wasn’t easy to learn.

“To be found dead on the side of the road—pretty dark, so sad, so lonely, unfortunate,” Gaida says.

People have suggested several theories regarding the cause of Smith’s death—everything from foul play to being struck by an avalanche—but Gaida is resigned to never knowing the details leading up to his demise.

“There’s no knowing what happened,” she says.

Despite Smith’s death before his 40th birthday, Dorworth says he was able to take some comfort in the fact that the passionate skier was found near Aspen.

“I was very relieved because … it meant that he had never left his roots—which were the mountains and skiing—even when he was destitute,” Dorworth says.

Gardner Smith Remembered

Gardner Smith in his Army uniform in 1952, photo courtesy Jeanne Gaida

Many details of Smith’s life, both on the slopes and otherwise, may be lost to history, but Gaida says mental health awareness can still be part of the story. She reflected on the discussion around the importance of mental health in recent years and lamented that her father was never able to get the help he seemed to need toward the end of his life.

“He was a pretty dynamic individual for this brief period of time, and things got cut short,” Gaida says.

Smith may also never be included among the heavyweights of American skiing, but his influence is felt through those he inspired, Dorworth says. Those people include Chuck Ferries, the first American to win the famed Hahnenkamm ski race in Kitzbuhel, Austria.

“(Smith) was a big influence on Chuck, and Chuck became one of America’s great skiers,” Dorworth says.

At least part of Gardner Smith will always stay in the Sierra Nevada. Gaida plans to bring some of her father’s ashes back to the mountains to reunite him with his parents and the area they all loved so much.

“He was as individual as they could come,” Gaida says, “and Gardner was always focused on being the best at his craft of skiing.”

Adam Jensen is a freelance writer who shares a love of skiing and a hometown of Modesto with Gardner Smith.

No Comments