27 Sep A Man Among Mountains

Orland Bartholomew’s three-month solo ski traverse of the Sierra Nevada was an improbable, groundbreaking feat that was nearly lost to history—today, it still inspires new generations of adventurous Sierra Nevada skiers

Orland Bartholomew

When Orland Bartholomew pushed off his rake-handle ski poles and began shuffling his hickory skis north toward the jagged peaks beyond Cottonwood Pass, the magnitude of the journey ahead must have been overwhelming.

He was alone on Christmas Day in 1928, heading into an unforgiving maze of 14,000-foot mountains in midwinter. He expected to be skiing for the next three months, traversing a giant-sized piece of the Sierra Nevada so daunting that even climbing legend Norman Clyde—perhaps the most rugged mountain man the range has ever seen—declined the invitation to join.

“Where would I sleep? What would I eat? What would I do when it stormed? If I broke a ski? Were taken ill? Went snow-blind? Were overtaken by an avalanche?” wrote Bartholomew in his journal upon setting out.

Of course, he had meticulously considered all of these things. He had durable custom skis, an ingenious tent, a down robe and a double-bit axe. He had placed 11 separate food caches along his route in a months-long pack trip into the High Sierra. He was ready. But even with all the preparation, Bartholomew’s plan was so audacious that all the planning in the world could not erase the danger.

He had charted a course that traversed the serrated spine of the Sierra Nevada from south of Mount Whitney to Yosemite Valley. At well over 200 miles, the scale of the ski traverse was visionary. And as if that wasn’t enough, Bartholomew planned to summit a few snow-clad 14,000-foot peaks along the way, including Whitney, which had never been climbed in winter.

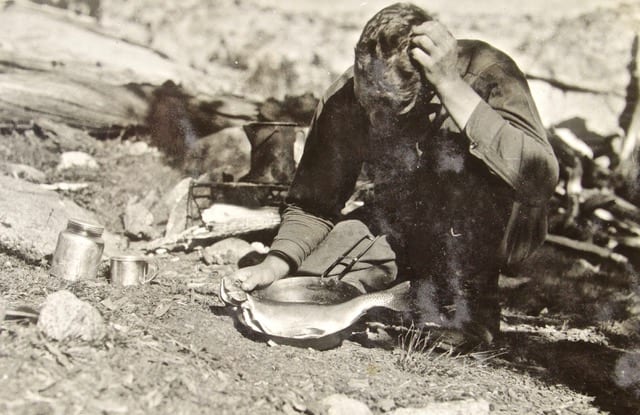

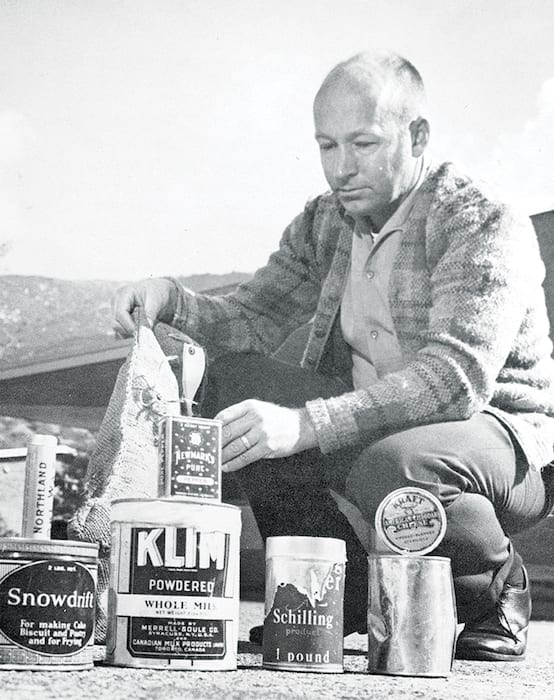

Bartholomew with a pan full of trout

Bartholomew was modest, humble and quiet. But his accomplishment was so awe-inspiring that it would eventually gain recognition as a landmark achievement in Sierra skiing history. Today, it still stands as the ultimate Sierra skiing test piece, and has become a legendary part of the lore of the mountain range passed down from rugged skier to rugged skier, inspiring new generations of adventurers for nearly a century.

“It’s the tops. It’s the premiere ski traverse,” says Tahoe-based adventurer Tom Carter, a pioneering Sierra Nevada skier in his own right. “No one had done it. When P-Nut [McCoy] and Doug [Robinson] did it, it was 40 years later.”

Tim Messick, a Yosemite skier and guidebook author who retraced Orland’s steps in 1999 with three other skiers, says the fact that Bartholomew did the route alone on 1920s ski equipment is astounding even today.

“Anything could have happened to him. It is a wonder anyone ever heard from him again,” says Messick.

The rugged southern end of Bartholomew’s route immediately threw him into the highest mountains in the continental U.S. It was a trial by fire that could make or break his ambitious plan right at the outset.

Bartholomew packed and ready to set off on a winter trip in the Sierra in February 1928, a year before his epic journey that is chronicled in High Odyssey

A Stream-Gauging Skier

Bartholomew was no stranger to surviving alone in the mountains in winter. He had traversed vast sections of the mountain range on skis as a stream gauger for Southern California Edison’s Big Creek Hydroelectric Project. Located in the mountains about 60 miles northeast of Fresno, Big Creek is the site of the nation’s first large-scale integrated hydroelectric project, and the stream gaugers delivered important specifics on the condition of the winter snowpack—the eventual engine of the electricity-generating turbines when spring temperatures spiked.

Bartholomew came across these Wolverine tracks in the snow near Glen Pass

He had also spent winters trapping pine marten, living alone in a cabin deep in the winter woods. He’d even traveled to Alaska in an unsuccessful attempt at mining.

So by the time he set out to ski the High Sierra, he innately knew how to read terrain, sense incoming weather and hunker down in a storm. And then there was his legendary stamina.

“Some say he was a mountain greyhound and could cover the rough distances of the high country faster than a horse,” wrote Gene Rose, author of High Odyssey, the definitive account of Bartholomew’s journey.

Still, the unavoidable danger of the journey was something that no amount of physical stamina, preparation or skill could entirely prevent. One slip on icy terrain, a bout of severe illness, an overpowering winter storm—any of a number of accidents or fits of Mother Nature could have left him pinned down alone deep in the wilderness.

Already, things had gone wrong. His only financial backing for the expedition—$1,000 from the San Joaquin Travel and Tourist Association—had been retracted. His only partner, Ed Steen, had abandoned the trip. Norman Clyde had turned down his invitation to join.

Still, Bartholomew shouldered his 65-pound pack and climbed above Cottonwood Pass, pointed toward the highest peaks in the country (Alaska had not yet become a state). Determination, it seems, was Bartholomew’s greatest gift.

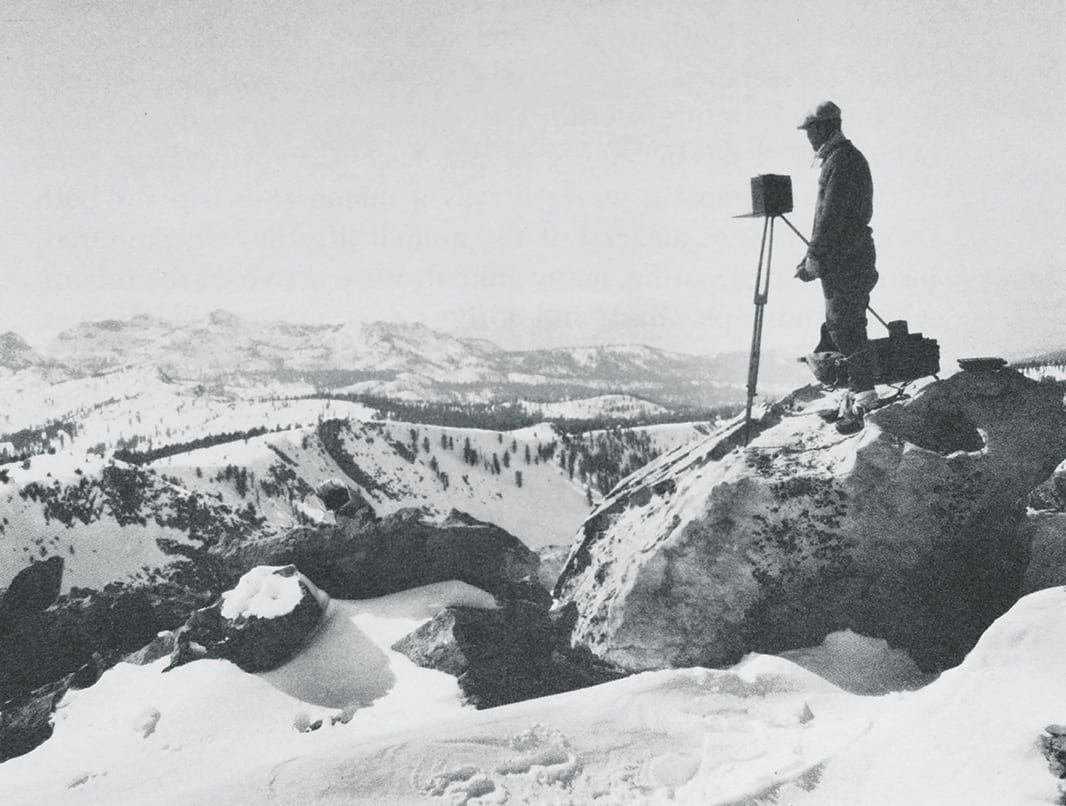

Bartholomew took this photo capturing the ridges of Mount Hale, with the Great Western Divide beyond, from near the summit of Whitney on January 10, 1929

Whitney in Winter

Bartholomew was literally pioneering the entire idea of Sierra ski traverses as he went. The range was in the middle of a golden age of mountaineering, but that had not spilled over into the snow-covered seasons. Seven years earlier, Francis Farquhar and Ansel Hall had put up the first ascent of 14,012-foot Middle Palisade. Two years before Bartholomew set out, Clyde had scaled the intimidating granite of Mount Russell—one of the last unclimbed 14,000-foot peaks in the range.

But as far as anyone knew, no one had climbed the landmark peaks in the winter. And the idea of long ski traverses was relegated to anomalous mountain feats like Snowshoe Thompson’s legendary mail carrier routes over the Sierra near Tahoe.

In fact, the entire idea of skis had limited acceptance in the Sierra Nevada when Bartholomew embarked on his three-month-long odyssey. Snowshoes were the tools of choice in that era. Bartholomew had to even custom order his own preferred hickory skis from a manufacturer in Minnesota. They were much shorter and substantially wider than regular skis of the era. To cement how unusual this skiing thing was, Bartholomew used rake handles for poles.

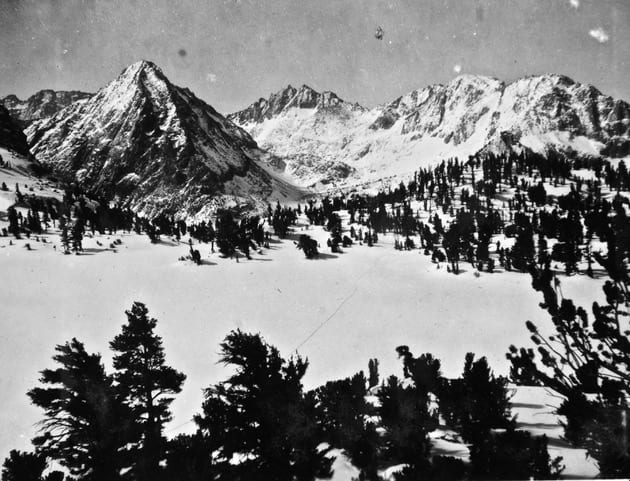

Mount Whitney from the summit of Mount Langley on January 4, 1929

Because this was virtually uncharted territory, Bartholomew inquired about previous winter ascents of Sierra Nevada peaks with the Sierra Club and even asked Clyde himself if he had summited Whitney in the winter. Clyde disavowed any winter ascent and the Sierra Club came up with no recorded winter ascent.

On his first attempt at Whitney, Orland was turned back by ice in a steep chute that shut off his upward progress. Then, in an almost casual ascent, he topped out on 14,026-foot Mount Langley.

“Went to cache for food and finished up by climbing Langley,” Bartholomew wrote in his journal. “And tho the impromptu ascent found me at the summit sans maps, thermometer, ice creepers and half the photographic equipment, it was my first winter ascent of a mountain above an altitude of 14,000 ft. and I returned to camp jubilant.”

Oddly enough, he saw a rabbit meandering the summit block of Langley. On top of the stark Sierra peak, he assembled his camera and took a series of stunning photographs.

Back at camp, Whitney sill loomed in his mind. After a careful study of maps, he decided on a route from the Mount Muir side of Whitney. After a “tight scramble around a pinnacled ridge” and a “few moments of floundering across a chute,” a single word punctuates Bartholomew’s journal—“dismay.”

“The north side, not only before me, but far below and for a considerable distance above, was too sheer to chance.”

But instead of retracing his steps, Bartholomew began pushing up the chutes on Mount Muir, hoping to work his way around the sheer rock wall.

The chute was not much easier going.

“The slope soon increased to precipitous proportions… handholds became icy and difficult.”

When he put his skis back on to work his way through a snowy section, Bartholomew dislodged a huge chunk of snow, which careened down the mountain out of sight.

Always the optimist, Bartholomew noted that this “uncovered some rocks to which I anchored until the disturbance was over.”

Bartholomew finally topped out at the Whitney Pass Trail, northwest of Mount Muir, and skied to the summit, where “the late hour forbade the reward such an ascent deserves.”

Still, he had time to set up the camera and take several self-timed photos, sign the summit register and take the temperature (26 degrees) before “the equipment was packed and a dog-trot begun down the mountain.”

That dog trot soon turned into a toboggan ride, as he lashed his skis together and rode them down the slope like a sled.

He had reached his highest point along the traverse. Now, all that was left was nearly three more months of battling snowstorms, skiing up and the down the rugged passes of the range, headed relentlessly north.

Bartholomew spent three days in this cabin near the south fork of the Kings River

Camera as Companion

Bartholomew’s journals are a detailed, day-by-day accounting of the trip. But the most stunning record of his trip is an unusually sophisticated array of hundreds of black-and-white photos he took along the way.

As early as 1925, Bartholomew had corresponded with Ansel Adams, the pioneering landscape photographer closely associated with Yosemite and the High Sierra. The questions he asked Adams presaged what would be a highly ambitious and unique photography quest, to capture hundreds of photos of the Sierra Nevada from such inhospitable places as the summits of Whitney and Langley in winter.

Bartholomew took this photo of East and West Videttes and Deerhorn Mountain from Bullfrog Lake by moonlight with 15-minute time exposure

The photography came with enormous complications. The camera equipment of the late 1920s was unwieldy and heavy. Shutter and camera mechanisms froze in the wind-whipped winter weather.

“Winter photography above timber-line encountered many unsuspected difficulties,” wrote Bartholomew in his journal. “No tripod can face the wind; even with guy-lines there would be a ruinous vibration … Snow blows into the shutter mechanism, tho it is too dry to stick to the lens… Fingers uncovered for fine adjustments are soon numbed… Each exposure is a triumph.”

Self-timer-triggered photos show Bartholomew on the summit of Whitney and skiing across ice-covered lakes deep in the Range of Light. Panoramic shots from Langley show an endless sea of peaks cloaked in snow, and many photos show Bartholomew as a solitary figure in this majestic winter landscape.

Bartholomew was meticulous about every aspect of his photography. He numbered each shot, stowed film carefully in caches along the way, and even made a point of mailing off his film to a carefully selected and trusted film developer partway through his expedition.

Orland’s son, Phil Bartholomew, says that photography was the true reason for his trip.

“He made the trip to take pictures,” says Phil, a retired fish biologist who lives in Oakhurst in the Sierra Nevada foothills just north of Big Creek.

With his mind so focused on the photography, the physical endeavor of skiing the High Sierra was almost an afterthought, says Phil.

“There was no question in his mind that he could successfully make the trip, because he had been living outdoors like that for years,” he says.

The photos are both stunning and pioneering. No one had previously photographed these deep, wild sections of the High Sierra in the winter.

To Yosemite

While Whitney, Langley and then Mount Tyndall represented the sky-scraping portion of the route, Bartholomew’s hardest mountaineering test ended up being Harrison Pass, an obscure and remote 12,700-foot pass that stands above the headwaters of the Kern River—a wild and austere country of wind-swept talus and barren lakes. Upon reaching the pass, Bartholomew found an icy cornice that, in his succinct and spare words, “gave considerable trouble.”

He ended up taking out his double-bit axe and placing snow creepers (rudimentary crampons) on his feet. He then chopped 150 steps into the ice to make a descent.

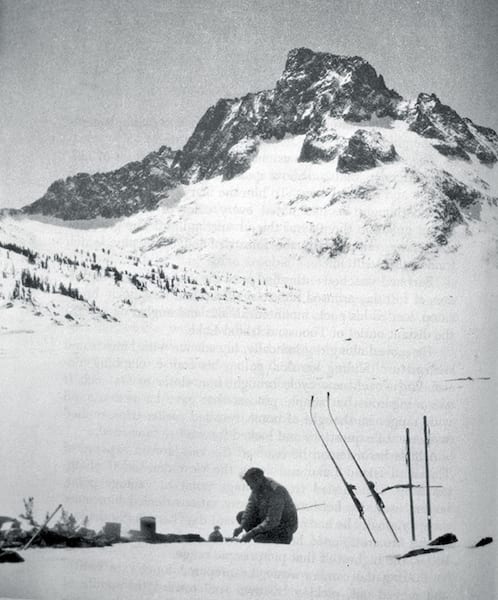

Bartholomew prepares a meal at Thousand Island Lake at the foot of Banner Peak

“The 300 foot descent took about 2 hours,” Bartholomew wrote. “With the heavy pack, and the skis swinging from my belt, the descent was really dangerous.”

Interspersed with these accounts of solo winter mountaineering danger are passages that give an insight into Bartholomew’s personality. Humor, wit and philosophical ruminations sprinkle the text.

“The long winter evenings would provide ample opportunity for study of the stars, and armed with a concise ‘Astronomy for Beginners’ I went forth among them. Alpha Centaura, I learned, twinkled only 25 billion miles away. Sweet companionship. I was not alone after all.”

In another section he solved a mystery: “For two months I had been puzzled by the odd flavor of some of the food—particularly the cereals. But at the Palisade cache the riddle was solved, the soap will hereafter be excluded from the big can. Mush de Wistaria. Hotcakes re Lilac. Phwew.”

“What is so interesting about it is how relaxed he was and what a sense of humor he had,” says Carter. “He was completely comfortable.”

Bartholomew faithfully noted each animal he saw or tracked, including a wolverine, porcupine and wolves.

The winter was turning out to be a lean one, and this was a mixed blessing. With fewer storms it was easier to break trail up the mountain range, but Bartholomew also encountered long sections of rotten and thin snow that had him punching through to brush and rocks below. He once dropped suddenly when a thin snow bridge collapsed.

After a short break in civilization at Independence, Bartholomew continued north toward Bishop. When he crossed Mather Pass, he found that the freeze-thaw of the warm winter had created sheets of ice along his route, some of which were crashing to the valley floor as the sun heated them. With ice tearing away from the slope all around him, Bartholomew retreated to the safe meadow below, in fear for his life.

“The danger was both real and imminent, and I am very tired this evening from the strain,” wrote Bartholomew.

Ahead, more unforeseen problems threatened the last leg of his trip. As he approached Mammoth, he found one of his food caches raided by hungry miners. He pushed northward to Yosemite in the warming spring weather with barely enough food and snow to finish the ski.

Phil Bartholomew displays cans of food that remained in one of his father’s food caches after 44 years. The cache was found in 1972 near Rae Lakes

An Enduring Inspiration

It’s hard to say how many people have repeated Bartholomew’s ski traverse in the 90 years since he completed it. But it is safe to say that the number is incredibly small.

Doug Robinson and P-Nut McCoy, son of Mammoth Mountain founder Dave McCoy, skied a similar route in 1970. Robinson recounts being pinned down by storms near Gabbot Pass and running out of food far from their next food cache.

“By the time we reached [the cache] we had been out of food for three days, subsisting on tea, vitamin B and weed,” Robinson wrote of the trip in an article in Backcountry Magazine.

Robinson, a veteran of ambitious rock climbing ascents and Himalayan expeditions, said “skiing the Sierra Crest with P-Nut was, step by gliding-northward step, nothing short of the finest expedition of my life.”

Carter, Allan Bard and Chris Cox channeled the spirit of Orland to establish the Redline Traverse, a Langley-to-Mammoth ski traverse that included a mind-boggling 50 mountain passes and 20 peaks while staying above 11,000 feet the majority of the route.

“We’d done a lot of ski traverses that were arduous,” says Carter. “The Redline was about redlining the fun meter.”

In preparing for the ski adventure, Carter says they would use Orland’s name as code for going all-in.

“We would say, ‘Are we going Orland?,’ meaning, ‘Let’s pack up and commit.”

In their 1984 Powder magazine article on the traverse, they pay homage to Bartholomew.

“This was not an original idea. In 1929, Orland Bartholomew soloed the first ski traverse of the High Sierra. Orland, equipped with a 25-pound down robe, rake handles for ski poles, and a desire for the high line, broke down the barriers,” the duo wrote in a seminal article on the adventure.

Although his time atop Mount Whitney was brief, Bartholomew managed to set up his camera and get a photo of himself signing the register

Like all great Sierra skiers, Carter knows his history. Bartholomew’s ski traverse may have been the pinnacle achievement in that period, but others of his era were pioneering what was possible in the Sierra Nevada.

Otto Steiner was putting down fast, light and long ski tours through the highest reaches of the range not long after Bartholomew. David Brower pushed deep into the Sierra in winter in the 1930s. And then there are the remarkable achievements accomplished in the Sierra Nevada without much fanfare.

“There is some really cool stuff that gets done in the dark,” says Carter.

Bartholomew may have even contributed to this legacy of humble yet Herculean mountain achievements. When he returned to civilization from the ski traverse, he did not go looking for recognition. In fact, he rarely ever mentioned his achievement.

“He just didn’t talk about it,” says Phil, his son. “And when you are a kid you don’t think to ask questions.”

Bartholomew had been hired by the U.S. Forest Service to man the guard station at Huntington Lake, high in the Sierra above Fresno, directly upslope from Big Creek. Phil’s first photo with his father is a shot of them skiing together when Phil was a toddler during a snowed-in winter day in the mountains.

“Before I could remember much of anything, he had me out in the mountains,” says Phil.

But the topic of that great Sierra adventure never came up, and only after discovering his father’s journal did Phil truly understand the trip.

“There is more in the diaries than I ever knew about him,” he says.

Bartholomew near the head of the Kern River, on the west slope of Mount Tyndall, in January 1929

Unlike Norman Clyde, who climbed long into his later years, or David Brower, Bartholomew never mounted another significant winter expedition. He married and raised kids, but still found ways to spend time alone in the mountains. He stopped taking landscape photos as well. But he did retain an intimate knowledge of flora and fauna of the mountains, and was sought after as an instructor because of his expertise in naturalism.

After a long career in the Forest Service, Bartholomew found himself first on the scene at the Source Point wildfire in 1949. He threw himself into fighting the blaze, but afterwards his health began to deteriorate, possibly from smoke inhalation during his firefighting duties, according to Gene Rose’s account in High Odyssey. By 1952 he had been discharged from the Forest Service with advanced emphysema, and he died in 1957.

Bartholomew’s achievement went virtually unnoticed for decades. Apart from an article he penned for the Sierra Club Bulletin, his ski traverse was known only by a few souls, until Rose, a journalist, used his copious journal entries to pen High Odyssey in 1987. Slowly, word spread, until Phil says he received inquiries about his father’s trips from as far away as Finland and Scotland.

In 1999, Tim Messick, Ostrander Ski Hut caretaker Howard Weamer, and Art and Fritz Baggett retraced Bartholomew’s steps on the 70th anniversary of the original ski tour. Armed with a copy of his journal, they skied for 28 days from Mount Langley to Yosemite.

“We followed his spirit across the Sierra Nevada,” says Messick. “We had these discussions, ‘Would he have gone this way or that way?”

The ski trip included many of the difficulties that Bartholomew faced. In fact, they encountered such cold and wind on Mount Whitney that Weamer’s middle finger on his left hand froze solid during the ski. Despite the frostbitten finger, he skied on.

Messick called the group a “modern day Bartholomew Fan Club,” and they did the expedition to raise awareness of the original ski traverse and request that Congress name a Sierra Nevada peak in Bartholomew’s honor.

“It was the highlight of my ski career,” says Messick.

But perhaps the most personal retracing of a portion of the route occurred in 1993. In that year, Orland Bartholomew’s son Mitch Bartholomew took his daughter Diana across much of the topography that her grandfather had pioneered.

“We traveled from Florence Lake through Blaney Meadows, up to Evolution Valley, then past Evolution Lake on the Muir Trail, over Muir Pass to the head of LeConte Canyon and back,” wrote Mitch. “It was a sentimental journey.”

They had with them the beautiful writings that Orland Bartholomew had penned decades ago as a lone traveler in this majestic wilderness.

“We would often stop in the high country and read what it was like for the grandfather she never knew to travel past that very spot alone in the winter more than 60 years ago,” wrote Mitch.

David Bunker is a Truckee-based writer and editor.

Ray Holm

Posted at 20:00h, 15 FebruaryCame across this great story I have heard before, in fact I grew up with Orland’s son Phillip in Big Creek, CA. Enjoyed hearing another version of the great trek across the Sierra’s. Ray