01 Dec Ancient Ice’s Last Stand

Glaciers have shaped the Golden State like no other natural force, but their days are dwindling

Turquoise blue, soft gray, iridescent silver, pearl white…

There’s something sublimely magical about the rich hues found in the ice layers of a glacier. It’s as if glaciers glow with the light of all the centuries they have seen, like time capsules of alpine sunshine and starlight trapped in frozen form.

The Whitney Glacier and Mount Shasta, as seen from Shastina in 1870, photo by Carleton E. Watkins, photo courtesy USGS

The wildly patterned facade of a glacier is a transfixing sight. Not only for the magnificent colors, but for the subtle feeling that you are in the presence of an ancient being. Glacial ice dates back hundreds, if not thousands, of years, yet the ice gives off the vibe that it’s still alive. And it is. Glaciers move and creak, moan and groan, just like a weary hiker. They are the original mountain travelers, slowly carving their own path as they flow downslope.

California may be better known for its sandy beaches than its ancient ice, but the Golden State is home to over 100 such stunning glaciers. It should come as no surprise, as much of California’s landscape was shaped by glaciers. This region has been home to these colorful and epically powerful geographical elders off and on for millions of years.

California’s glaciers are tucked away in the highest reaches of the Sierra and Mount Shasta. They cling to steep mountain faces and are spectacular destinations for the adventurous explorer. They are also important environmental messengers. Glaciers are sensitive indicators of climatic change, both historically and in modern times. When the earth is cool, glaciers grow, and when the earth is warm, glaciers recede.

The glaciers in California, and everywhere in the world, are rapidly melting. This is unmistakable evidence that global warming is real and has already begun to permanently transform the earth’s ecosystems. Scientists widely believe that no matter how much humanity cleans up its act in the next 50 years, the damage is already done. Many glaciers will not survive another 50 years, especially in California where our glaciers are already relatively small.

We will likely be the last generation to experience glaciers in California. As disturbing as this sounds, it should also be motivating. Now is the time to learn about these incredible geological phenomena and to see them before they are gone.

Allison Lightcap drops into a dream run down Mount Shasta’s Whitney Glacier, photo by Seth Lightcap

Living in an Ice Age

The first step in understanding the importance of glaciers in California is to understand what glaciers are and how they form.

By definition, glaciers are bodies of snow and ice that do not melt during the summer and that are thick enough to slowly move downhill with gravity under their own weight. Water flowing underneath glaciers reduces friction, allowing them to slide over rough rock and carve out the land as they move. If a snow or ice patch lasts through the summer but is not thick enough to move, it is not a true glacier. Stagnant perennial snow patches are known as ice bodies.

The state’s last remaining glaciers are located in the High Sierra and Mount Shasta, while the formerly glaciated Trinity Alps and Lassen Peak hold several perennial ice bodies, map courtesy USGS

Glaciers are born from “ice ages”—time periods during which a slight change in the earth’s orbit relative to the sun encourages cold temperatures and ice growth. Ice ages are marked by the formation of massive, continental-sized glaciers called ice sheets that grow out from the polar regions and cover huge regions of the planet’s surface. There have been at least five ice ages in the earth’s history. An ice age ends when the earth warms enough to melt all the ice sheets on the planet. When the ice is gone, earth enters what is known as a greenhouse period.

Within each ice age there are also intermittent climatic pulses that influence the glaciers present on earth. Cool periods within an ice age, when glaciers are at their height, are known as “glacial” periods. Warm spans within an ice age, when most but not all the glaciers and continental ice sheets melt, are known as “interglacial” periods.

The last ice age, known as the Pleistocene Glaciation, began about 2.6 million years ago. There were several glacial and interglacial periods within the Pleistocene during which the ice sheets alternated between growing and melting back. The last glacial period within the Pleistocene, when ice sheets were at their maximum, occurred only 25,000 years ago. The Sierra Nevada, Mount Shasta, Lassen Peak and the Trinity Alps were covered in large areas of interconnected glaciers known as ice fields during this last glacial phase. These massive glaciers carved the alpine regions into the landscapes we see today, leaving jagged cliffs and massive canyons like Yosemite Valley in their wake.

This glacial period that did much of the work shaping the Sierra ended around 10,000 years ago. Scientists believe that all the glaciers in California completely disappeared at this time. Not all the ice sheets on earth melted though. Two of the biggest ice sheets from this last glacial period survive to this day—the Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets. Because these ice sheets still exist, we are technically still living in an ice age.

The glacial melt-off 10,000 years ago marks the beginning of our current scientific time period, known as the Holocene. The Holocene is an interglacial period, so, as the theory goes, glaciers should be retreating. But, to confuse the matter, the glaciers we have in California today were formed during this supposed warming period. Recent studies suggest that some glaciers started reforming in California around 3,500 years ago, but most of our current glaciers were born only 200–700 years ago during a relatively short climatic shift called the Little Ice Age.

The Little Ice Age was a time period between the fifteenth and nineteenth centuries when many regions on earth entered an anomalous cooling period. Several theories exist about possible causes for the Little Ice Age, including altered ocean currents, weakening solar radiation and volcanic eruptions that released plumes of sunlight-blocking ash into the atmosphere. California’s glaciers grew significantly during this 500-year time window of cold winters and cool summers. The Little Ice Age ended around 1850 and the glaciers immediately responded by starting to recede leading into the twentieth century.

The Middle Palisade Glacier in Kings Canyon National Park pictured in August, photo by Seth Lightcap

Taking Inventory

Glaciologist and geographer Hassan Basagic is one of the foremost authorities on which glaciers still exist in California from the Little Ice Age. In 2011, Basagic, along with Dr. Andrew Fountain of Portland State University, published a landmark thesis that documents the inventory of glaciers remaining in the Sierra Nevada and their rate of change in the twentieth century.

“While knowledge of glacier shrinkage in the Sierra was common, there was little quantitative information on the magnitude or rate of reduction,” says Basagic. “The goal of my thesis was to define the number of glaciers in the Sierra and figure out how fast they were truly shrinking. The results were definitely eye-opening.”

Using topographical maps and satellite images, Basagic and Fountain estimate that there are over 1,700 perennial snow and ice bodies in California. A vast majority of these ice bodies are not true glaciers because they do not move. They estimate that there are approximately 118 glaciers in the Sierra and seven glaciers on Mount Shasta that are still moving. Lassen Peak and the Trinity Alps no longer hold any true glaciers, though they are home to several perennial ice bodies.

Of the 118 glaciers Basagic and Fountain identified, the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) has named and recognized 20, including 13 in the Sierra and each of the seven on Mount Shasta. Skiers and snowboarders will recognize many of the named glaciers as some of the premiere backcountry descents in the state, including the Palisade, Conness, Dana and Darwin glaciers in the Sierra, and the Whitney, Hotlum, Bolam and Wintun glaciers on Shasta.

Almost all of the USGS-named glaciers are found in protected north- or northeast-facing mountain cirques above 10,000 feet in elevation. Hence, all but one of the named glaciers are classified as “cirque glaciers,” meaning the glacier sits in a small spoon-shaped depression at the head of a valley. The Whitney Glacier on Mount Shasta is California’s longest glacier. Stretching over 3 kilometers, the Whitney is classified as a “valley glacier” because it occupies both the cirque and the valley below. The biggest glacier in the Sierra is the Palisade Glacier in Kings Canyon National Park, which is 1.3 kilometers long.

Yosemite’s Dana Glacier in 1883, photo by I.C. Russell, and again in 2013, photo by Hassan Basagic

Following Photo Footprints

Basagic’s and Fountain’s work documenting California’s glaciers follows up on over a century of previous research by many esteemed geologists. The concept of glaciers altering mountain landscapes had been known for centuries in Europe, but “living” glaciers that were proven to move were first discovered on Mount Shasta and in the Sierra by naturalists Clarence King and John Muir in the 1870s. Muir conducted motion experiments on the Maclure Glacier in Yosemite by placing stakes in the ice and tracking their movement over the course of a couple of months. He calculated that the glacier was moving at a rate of an inch per day.

Some of the most important early glacial research in California began in 1883 on an expedition led by I.C Russell of the USGS. Russell took photographs and drew maps of all the glaciers he could access in the Sierra, plus many of the glaciers on Mount Shasta. These early photos and maps laid the foundation for a glacial research technique known as repeat photography. By taking a photo from the same spot 10, 50 or 100 years apart, scientists can estimate how much surface area a glacier has lost in the time period between photos.

Basagic and Fountain used repeat photography along with satellite imagery and field mapping in their 2011 study. They have since returned to the glaciers they studied and taken new photos to update their findings to 2014.

“Repeat photography has the unique ability to compress time,” says Basagic. “It’s fascinating to observe remote landscape changes over a century, how massive ice can vanish, all in an instant of geologic time.”

Basagic and Fountain have now organized all their glacier photos from the Sierra and other ranges in the Western United States in an online database called the Glacier RePhoto Project. The photo database seeks to organize the existing glacier repeat photographic record by location and acquire new repeat photographs. They have collected over 1,300 repeat photos from 270 locations, and their collection grows each year.

Conness Glacier in 1957, photo by Bill Dumire, and in 2013, photo by Hassan Basagic

Harsh Reality in the Sierra

By analyzing photos and field data, Basagic and Fountain were able to determine the approximate loss of glacial surface area and rate of change for a set of seven glaciers spread out over a 200-mile swath of the High Sierra. The selected glaciers were the Conness, Darwin, East Lyell, West Lyell, Goddard, Lilliput and Picket.

The results of their research determined that the selected glaciers lost an average of 70 percent of their surface area between 1903 and 2014. The losses ranged from 48 percent to a whopping 83 percent. The East Lobe of the Lyell Glacier in Yosemite shrank the most.

“The loss of the glaciers in the Sierra Nevada is troubling, not only for the environmental consequences on alpine flora and fauna, but for the fading human experience of visiting glaciers,” says Basagic. “Their presence on the landscape encourages adventure and nourishes the soul. Glaciers also act as outdoor classrooms, where you can observe the processes that literally moved mountains and sculpted the places we love to play.”

The two researchers also calculated the rate of glacial change in the Sierra over time. Their results indicate that Sierra glaciers began rapidly retreating in the 1920s and consistently shrank through the 1970s. Big winters in the early 1980s paused glacial retreat in the Sierra for a few years, but the rally was short-lived. All seven study glaciers not only resumed retreating in the late-80s, but the shrinkage rates drastically increased. Data suggests that about half of the total glacial loss in the Sierra has occurred since the 1970s.

Once covered in large areas of interconnected glaciers, the Trinity Alps no longer hold any true glaciers, photo by Sylas Wright

Catastrophe in the Trinity Alps

No mountain region in California has suffered from glacial loss in the last decade more than the Trinity Alps. Located in Siskiyou and Trinity counties near the town of Weaverville, the Trinity Alps are a subrange of the Klamath Mountains and top out at a much lower elevation than the Sierra. The tallest peaks in the Trinity Alps are only 9,000 feet. The towering north-facing walls on the crest of the range are ideal locations for glacier formation, however, as the topographical shading protects collected snow and ice from the intense summer sun.

In the late 1880s, at the end of the Little Ice Age, at least five glaciers and dozens of perennial ice bodies existed in the Trinity Alps. These glaciers were the lowest and western-most glaciers in California, located 1,700 feet below any glacier in the Sierra. Three of these glaciers stopped moving around the mid-twentieth century and became perennial ice bodies, while two, the Salmon and Grizzly glaciers, held on into the twenty-first century.

Basagic and Fountain, along with researchers from the California Department of Fish and Wildlife, have monitored the Salmon and Grizzly glaciers for the past couple of decades. In a 2020 study, they report that an extended drought between 2012 to 2016 resulted in the catastrophic retreat of both glaciers. The Salmon Glacier completely disappeared in 2015 and the Grizzly Glacier had lost 97 percent of its surface area and stopped moving.

The massive loss of glacial ice in the Trinity Alps in the past decade has not been echoed on neighboring Mount Shasta. While Shasta is less than 100 miles away from the Trinity Alps and sits at the same latitude, the peak is significantly higher in elevation, which has tempered some of the effects of climate change on the mountain until recently.

Mount Shasta in the southern Cascades boasts the only south-facing glaciers in California, photo by Seth Lightcap

Mount Shasta’s Climate Roller Coaster

Topping out at 14,179 feet and boasting the largest volume of any mountain in the Cascades, Mount Shasta is one of the largest stratovolcanoes in the world. All that surface area offers ample real estate for the biggest and most active glaciers in California. Among the mountain’s seven glaciers, a few of them boast some impressive attributes.

The Whitney Glacier, located on the north side of the mountain, is the longest glacier in the state. The Hotlum Glacier, located on the east side, is the thickest and biggest by volume. And the Mud Creek, Konwatikon and Watkins glaciers are the only glaciers in California with a southeasterly slope direction. Beyond the seven named glaciers, some scientists propose that there are three additional glaciers on Mount Shasta, but it’s controversial whether these three small ice bodies move continually enough to receive the classification.

What’s also unique about the glaciers on Mount Shasta is their response to climate change over the past 50 years.

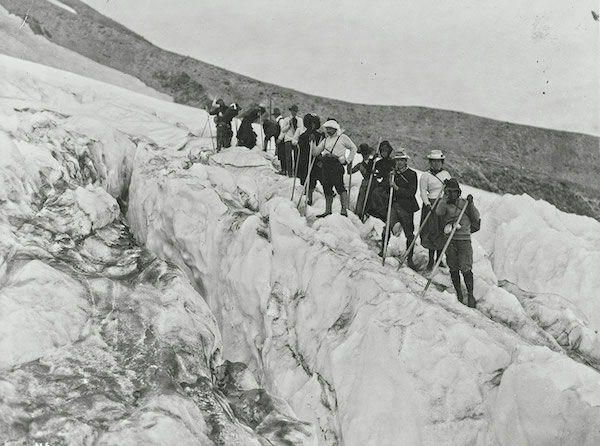

Mountaineers explore the bountiful Whitney Glacier ice on Mount Shasta in 1901, photo courtesy Library of Congress

In 2008, Mount Shasta made global news when a study was published by researchers at U.C. Santa Cruz stating that the glaciers there had grown almost continuously from 1950 to 2003. The study found that Mount Shasta had received increased levels of precipitation since 1950, which resulted in the high-elevation glaciers receiving more snowfall. The additional snowfall had been enough to overcome the rise in average annual temperature due to global warming. This caused the glaciers to grow more each winter than they shrank each summer. The study reports that the Whitney Glacier had advanced 850 meters, or approximately 30 percent of its length, and that the Hotlum and Wintun glaciers had nearly doubled in size since 1951.

This phenomenon of glacier growth due to increased precipitation had also been identified in mountain ranges in New Zealand, Norway, Sweden and Pakistan in the 1990s. But such news in all those ranges, and on Mount Shasta, was fleeting. More snowfall had temporarily offset warming temperatures, but rising temperatures have now won out and the glaciers in all of these regions are now shrinking. Studies suggest it takes a 20-percent increase in snowfall to overcome a 1-degree temperature increase.

Dr. Mauri Pelto, a glaciologist and professor of environmental science at Nichols College, has studied glaciers in the Cascades for the past 35 years. In a 2014 satellite image analysis, Pelto found that the Whitney Glacier had already retreated 700 meters since 2005, nearly erasing the growth over the previous 50 years.

“Overall precipitation has not decreased in the Cascades, but snowpack and glacier mass have,” says Pelto. “More precipitation is not a climate scenario that will work for Pacific Northwest glaciers. We have also already seen that increases in winter season temperatures are causing the snow-to-precipitation ratio to decline, indicating more winter rain, and therefore more glacial melt.”

Pelto also notes that, while Mount Shasta’s glaciers have been affected by rising temperatures, the losses have been less severe than Cascade glaciers in Oregon and Washington. Recent studies estimate that the Cascades have lost 48 percent of their glacier surface area since 1900.

“Shasta’s glaciers have a higher mean altitude and are smaller than many other glaciers in the Cascades. This has led to an overall less dramatic loss in the last couple decades,” says Pelto.

Mount Shasta’s glaciers are also faring better than many other mountain ranges in the Western United States. According to a paper published in 2020 by Basagic and Fountain, glacier surface area in the Colorado Rockies diminished 40 percent from 1909 to 2004, the Wind River Range in Wyoming dropped 47 percent from 1900 to 2006, and the Olympic Peninsula in Washington registered a 34-percent decline from 1980 to 2009. In a broader study, Fountain estimates a 39-percent decrease in glacier surface area throughout all glaciated regions of the Western United States between 1955 and 1990.

On a global level, the World Glacier Monitoring Service, an international organization that tracks glacier data, reports that the rate of worldwide ice loss has almost doubled in each decade since 1970, with eight out of 10 of the greatest loss years occurring after 2010.

Melting glacial ice near the terminus of the Whitney Glacier on Mount Shasta, photo by Seth Lightcap

Four-Season Playgrounds

Despite all the grim reports, there is still much to be celebrated about California’s glaciers. The best news is that all of the glaciers in the state are still stunning adventure destinations worthy of exploration in any season.

If you visit a glacier in the summer or fall, you can expect to see the volume of remaining ice that is actively moving down the mountain. This “living” body of the glacier is where the most beautiful ice colors and features are found. Depending on the glacier, the ice may be broken up in some areas by deep and dangerous cracks called crevasses. It’s important to stay away from crevasses, as these areas are typically where the ice is the most unstable. Crevasses may also extend much farther than is visible. Falling into a crevasse can be a fatal mistake considering how far any glaciers are from medical help.

There are several glaciers in the Sierra and on Mount Shasta that can be visited in a summer day hike. The Conness and Dana glaciers at the eastern edge of Yosemite are two of the easiest to reach. On Shasta, the base of the Hotlum and Wintun glaciers are just a couple-hour hike from the Brewer Creek trailhead. The Hotlum is an especially impressive sight, even from a distance, as the glacier is riddled with icefalls and crevasses similar to glaciers found in Alaska.

Come winter, exploring California’s glaciers is a more involved adventure that requires solid backcountry touring and avalanche rescue skills. Skiing on a glacier presents challenges and dangers beyond what is normally found touring on non-glaciated terrain. Not only is avalanche danger a concern, but you must also be extremely careful to avoid skiing into a crevasse. If traveling on a glacier that has a lot of crevasses, you should have glacier rescue equipment and training in glacier travel. Most glaciers in the Sierra and Shasta are not heavily crevassed, however, and there are many glacial runs to ski that do not require advanced glacier travel skills.

When Tioga Pass opens in the late spring, the Conness and Dana glaciers are classic backcountry ski tours that hold a ton of epic descent options. Just as in summer, both can be accessed in a day. If you are ready for an overnight adventure, or a huge day tour, the Palisade Glacier is one of the finest backcountry ski descents in the Sierra.

Every glacier on Mount Shasta is an amazing backcountry ski descent as well. The Upper Wintun and the side of the Hotlum Glacier are two of the safest and easiest tours. Expert skiers with glacial travel experience and knowledge of Mount Shasta’s topography will enjoy exploring the Whitney and Konwakiton glacial zones.

Brennan Lagasse carves a track into the Goethe Glacier, one of the smallest glaciers in the Sierra, photo by Seth Lightcap

The Time is Now

Perhaps even scarier than skiing into a crevasse, it’s quite possible that the earth may not start cooling again for another 100,000 years—if we’re lucky.

Climate scientists now believe that the amount of carbon dioxide humans have pumped into the atmosphere since the industrial revolution will cause the earth to skip any potential cooling period or ice age that would have otherwise been initiated by cyclical changes in the earth’s orbit. Over the past millions of years, a combination of low sun angle in the northern latitudes combined with low carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere has been earth’s signal to cool. But now, with carbon levels nearly double that of a century ago, any cooling effect of the earth’s cyclical orbit will be erased by the greenhouse effect of the increased carbon.

So, what does that mean for California’s glaciers? It means the glaciers we have now, the glaciers that have already lost 70 percent of their surface area, will be the last ones in California for well beyond the imaginable future of humanity.

This reality presents an opportunity for something special in our lifetime. Glaciers have been the single most powerful natural mechanism to shape many of our favorite places in California. We will be the last generation to be able to honor them with our efforts to go explore them. So, take a day this winter, or next summer, or the winter after, and hike up to a glacier. Your footprints or ski tracks may just be the last tracks those living ancient ice crystals ever see.

Seth Lightcap is a Squaw Valley–based writer, photographer and avid explorer of Sierra rock, snow and trail. See more of his stories at www.sethlightcap.com.

John of the Mtns

Posted at 08:59h, 06 OctoberI am surprised you didn’t mention anything about glaciers in our home region, How glaciers helped create Lake Tahoe, Emerald Bay and carve out most of the West Shore/Sierra Crest. They even named a glaciation event after Tahoe..