25 Jun As the Old Crow Flies

Tahoe’s own World War II triple ace fighter pilot Bud Anderson ruled the enemy skies above Germany in his P-51 Mustang

Bud Anderson sits on the wing of his trusty P-51D during World War II, courtesy photo

Like many boys his age, a young Bud Anderson would run through his yard with a toy airplane held high over his head, dreaming of flying around the clouds with his own set of wings one day.

From that childhood dream, he would grow to become one of the most fearsome combat fighter pilots of World War II, shooting down more than 16 enemy planes in his P-51 Mustang, “Old Crow,” in the hostile skies above Germany.

Anderson flew two combat tours and 116 missions in World War II, logged countless combat hours and never once was hit by enemy fire or turned back from a mission. He went on to command a squadron of F-86 jet fighters in post-war Korea and, at age 48, flew combat strikes in an F-105 Thunderchief during the Vietnam War in 1970.

“In an airplane, the guy was a mongoose,” General Chuck Yeager writes in the foreword of Anderson’s autobiography. “It’s hard to believe, if the only Bud Anderson you ever knew was the one on the ground. Calm, gentlemanly. A grandfather. Funny. An all-around nice guy. But once you get him in an airplane, he’s vicious. Shot down 17 airplanes. Best fighter pilot I’ve ever seen.”

The recipient of 26 distinguished awards during his 30-year military career, Anderson was inducted into the National Aviation Hall of Fame in 2008.

Today, Anderson, who remains sprightly and sharp at 98 years old, enjoys living in Auburn and visiting his second home on Lake Tahoe’s North Shore, where he has spent many family holidays since the 1950s. For the past seven years he has captivated crowds as the featured speaker at the Truckee Tahoe Air Show, sharing in remarkable detail his many spellbinding stories of combat. He returns to the air show by popular demand as grand marshal this fall.

Still sharp at 98 years old, Bud Anderson continues to share his spellbinding stories of combat at air shows across the country, including the Truckee Tahoe Air Show, courtesy photo

Born to Fly

The third of four children, Anderson was born in Oakland on January 13, 1922. He was raised on a fruit farm in the Sierra foothills near Newcastle, where his family grew apples, cherries, nectarines, peaches, plums, pomegranates and pears. In the 1920s and early ’30s, the Anderson family would pack their car and drive to Lake Tahoe to camp in tents near Meeks Bay.

“It was like an expedition,” Anderson recalls. “The roads were primitive in those days, but I remember the breathtaking views. To this day, I still love Lake Tahoe.”

Years later, while stationed in Tonopah, Nevada, as a young fighter pilot, Anderson had the opportunity to lead a flight of P-39s over the wide-open blue expanse of Lake Tahoe. It was an experience he’ll never forget.

“It was one of those calm summer days when there wasn’t a ripple on the surface. It was glass,” says Anderson. “So, we got down to about 50 feet over the center of the lake. The blue was so intense it was like a mirror, and it reflected on us turning our aircraft into a deep blue, like the lake itself. There is no place so beautiful, so serene, as Lake Tahoe. It’s one of the most beautiful spots on earth.”

Anderson’s interest in airplanes dates back to when he was 5 years old and Charles Lindbergh had safely crossed the Atlantic Ocean in the Spirit of St. Louis. Something about that accomplishment stuck with him his entire life.

But that was not the only aviation event that shaped Anderson as a child.

When he was 7, he and his best friend, Jack Stacker, crawled through the wreckage of a Boeing Model 80 biplane that crashed less than 3 miles from Anderson’s home the previous night (all on board survived).

“After these two events, all I talked about and dreamed about were airplanes, airplanes and airplanes,” says Anderson, who received his private pilot’s license at age 19 in a Piper Cub.

A year later, in 1942, he earned his military pilot wings in an AT-6 Texan.

“This was no Piper Cub. This was flying,” Anderson says of the AT-6 Texan, an advanced trainer plane used to prep U.S. military pilots. “This was wheeling and soaring and diving fast enough to raise the hair on the back of your neck. This was fun. There was more grace and power than an eagle dared dream of, right there at my fingertips. This was how I’d envisioned it, how I’d thought being a pilot would be—only better.”

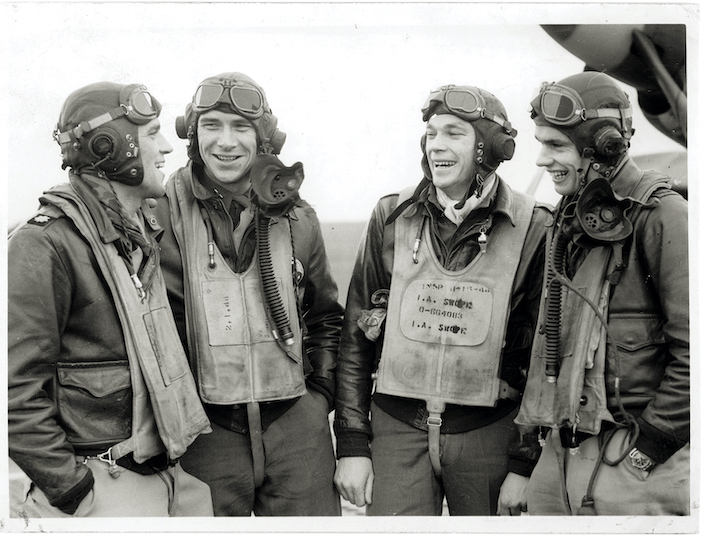

Four members of the 357th fighter group’s “Yoxford Boys,” from left, Richard “Pete” Peterson, Leonard K. “Kit” Carson, Johnny England and Bud Anderson, courtesy photo

The Real Top Guns

Anderson’s first duty assignment was in the San Francisco Bay Area, where he joined a fighter pilot replacement training group flying P-39 Airacobras.

He anticipated that he would be attached to a combat unit in North Africa or the South Pacific, where P-39s were being employed. Instead, he learned that he would be among the first members of a new fighter group, the 357th, and he would be one of their flight leaders.

Three months later Anderson’s group boarded the ocean liner Queen Elizabeth and sailed to Great Britain. To the pilots’ delight, they discovered they would be flying P-51Bs, the first Mustangs with the powerful Rolls-Royce Merlin engines.

“It was our first time seeing the P-51s. You could say it was love at first sight,” says Anderson. “The P-51s were much more powerful and nimble than anything any of us had ever flown.”

With long-range bomber escorts in high demand as the U.S. launched a massive offensive, the 357th joined the Eighth Air Force, conducting its first mission in February 1944.

From left, Yoxford Boys Richard “Pete” Peterson, Leonard “Kit” Carson, Johnny England and Bud Anderson collectively recorded nearly 70 victories during the Eighth Air Force offensive in 1944, courtesy photo

The 357th was no ordinary group of pilots. They were all 10 feet tall with swagger like John Wayne and talked tough like Humphrey Bogart. Or at least that’s what they believed. They were known as the “Yoxford Boys,” after the village near their base on England’s east coast.

Aside from Anderson, who would earn 16 ¼ aerial victories, this skillful group featured three other triple aces: Leonard “Kit” Carson (18 ½ victories), Johnny England (17 ½) and Richard “Pete” Peterson (15 ½). They were confident, self-reliant, aggressive and proud of it.

“Only the fittest and most competitive survived the training, and then the deadly winnowing imposed by our last and best teacher, the German Air Force,” says Anderson.

The 357th would score 595 aerial victories, placing them in the top five of all U.S. Army Air Forces groups in World War II. Notably, the 357th accomplished its staggering number of victories in only 14 months of combat.

“We were fighter pilots, flying the damnedest, fastest, most lethal airplanes anyone ever dreamed up, the forward line in defense of the entire free world… with egos that would make Mussolini look humble,” says Anderson.

Despite its success—the group shot down five enemy planes for each one it lost—the 357th also suffered heavy losses. Half of Anderson’s original squadron of pilots were killed or captured. Jack Stacker, Anderson’s childhood friend, was killed in combat flying a P-38 on his fifth mission over Germany in November 1943. He and his widow, Ellie Cosby, had spent only one week together after their wedding before Stacker left for war.

Life or Death: The Thrill of a Dogfight

One of Anderson’s most intense combat encounters took place on May 27, 1944. He was escorting heavy bombers on a raid deep into Southern Germany when his flight of four P-51 Mustangs was attacked by four ME 109s. Four-on-four.

Anderson broke the Germans’ attack and then turned the tables on them. Over the next 20 minutes he and his pilots shot down two of the four enemy aircraft. Of the remaining two, one ran away and the other turned to fight. Anderson engaged with the remaining German fighter pilot.

“I’m in this steep climb, pulling the stick into my navel, making it steeper and steeper… at nearly 28,000 feet and I’m looking back down, over my shoulder, at this classic gray ME 109 with black crosses pulling up behind me, the pilot trying to get his nose up just a little bit more and bring me into his sights, right on my tail,” says Anderson.

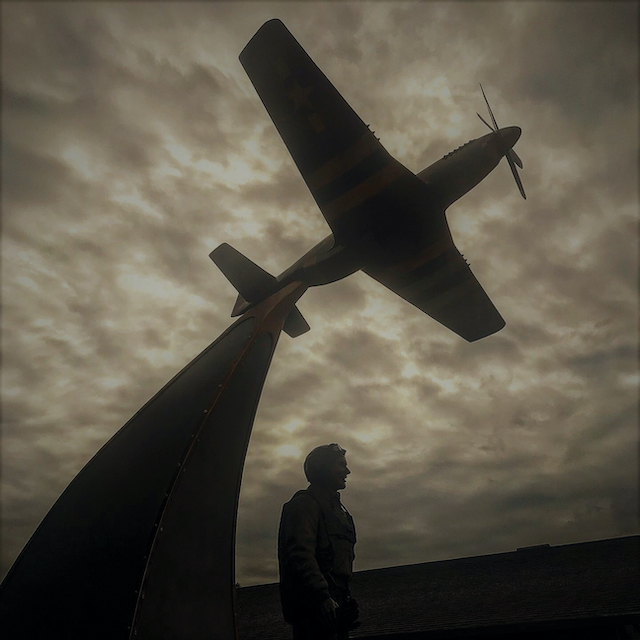

A bronze statue of Bud Anderson and his P-51 Mustang, “Old Crow,” on display at the Auburn Municipal Airport, photo by Michael Kennedy

“He was someone trying to kill me with a gun designed to bring down a bomber—one that fires shells as long as your hand, shells that explode and tear big holes in metal. It’s the single most frightening thing I’ve ever experienced in my life, then and now.”

Anderson knew his Mustang could outperform the ME 109, especially in a vertical assault. He just needed to outpace his opponent while dodging the massive firepower coming from behind. The ME 109 began to stall, forcing the pilot to turn and dive. This gave Anderson the upper hand as he dropped in on his rival’s tail. Now, Anderson was chasing the enemy, following him into a climbing left turn.

During the final minutes of this high-altitude fight, Anderson unleashed his firepower into his opponent’s plane, scoring multiple hits. The severely damaged ME 109 went into a nosedive, straight down with a mile of black smoke from 27,000 feet into the ground, followed by a tremendous explosion.

Anderson had outmaneuvered a capable adversary. As a result, he lived, and his enemy died. For that, he credits the airplane he flew. “It was made in America,” he says. “I would live to see the day when people would try to tell me the United States can’t make cars like some other folks do. What a laugh.”

Like most aces, Anderson named his P-51. “Old Crow,” as Anderson tells his non-drinking friends, was named “after the most intelligent bird in the sky.” But to everyone else, he admits the name comes from “that good old Kentucky straight bourbon—the cheapest thing back then.”

On another occasion, Anderson tangled with a German Focke-Wulf 190 that was threatening the bombers his squadron was protecting.

“I dove after him and he kept going down, steeper and steeper, faster and faster, tempting all the known laws of physics, trying to shake me,” says Anderson. “We were pressing the redline, approaching 500 miles per hour. Neither the Focke-Wulf nor the Mustang were designed for anything much beyond that. Any faster and the wings could tear off.

“But I was determined. I would go wherever he went, do whatever he did. I wanted a victory.”

Anderson ultimately backed off due to rules of aerial engagement.

In another hard-fought battle, again with an ME 109, Anderson and the German pilot flew offset intersecting paths as they repeatedly passed each other in close-range circling combat, neither pilot able to fire.

As Anderson described to Aviation History magazine in a 2012 interview: “I decide to pull my sights through the German until I can’t see him, then fire, hose him and hope against all odds that he flies through the bullet stream.

“I pull up and around and fire off a quick stream of tracer as he disappears under me. I ease off the stick and he flies into my view. Hot damn! He’s spilling coolant back into his slipstream. I got him! And while I’m whooping like I’d just scored the touchdown that won the Rose Bowl, he throws the canopy off and bails out. His 109 goes straight in.”

Anderson continued his success, recording 12 ¼ victories during his first combat tour. He returned for a second tour two months later and added four more victories before the end of the year.

Just as he dreamed as a young child, Bud Anderson flies through the clouds in his World War II fighter plane, Old Crow, courtesy photo

Living on the Edge

Despite his skill and confidence, Anderson admits that the threat of not returning from a mission was ever-present in his mind.

“Fear of the unknown was the thing that worried us the most,” he says. “I had over 900 total hours of training prior to combat. But when training, no one is shooting at you. It’s a different thing altogether when you’ve got someone on your six firing weapons at you, trying to take you down.

“In combat, just flying over enemy territory is scary. If they blow you out of the sky and you manage to parachute safely to the ground below, your hell is just beginning. My attitude was simple: If I wasn’t going to make it, I was going to give the enemy everything I had.”

After surviving the Second World War, Anderson performed hazardous work as a test pilot. He commanded a fighter squadron in post-war Korea and a fighter wing on Okinawa and Vietnam. He retired in 1972 after 30 years of active duty in the United States Air Force.

Anderson, who has flown more than 100 types of aircraft in his career, admits that good fortune helped keep him alive during his many high-risk missions. But while luck certainly played a role, he says his keen situational awareness, exceptional colleagues and incredible eyesight helped too. Anderson had 20/15 vision in one eye and 20/10 in the other, allowing him to spot objects in the sky long before anyone else, a tremendous advantage without the advanced technology of today.

“My ability to identify aircraft gave me an edge,” he told Aviation History. “I was always good at it. We would train with a slide projector, flashing silhouette images, and I generally identified them all, bang-bang-bang. Part of that probably traces back to my fascination with planes as a kid, making models. But part must be physical. My eyes, I’ve always believed, communicate with my brain a bit more quickly than average. And I wanted to see them. I might have been a little more motivated than most.”

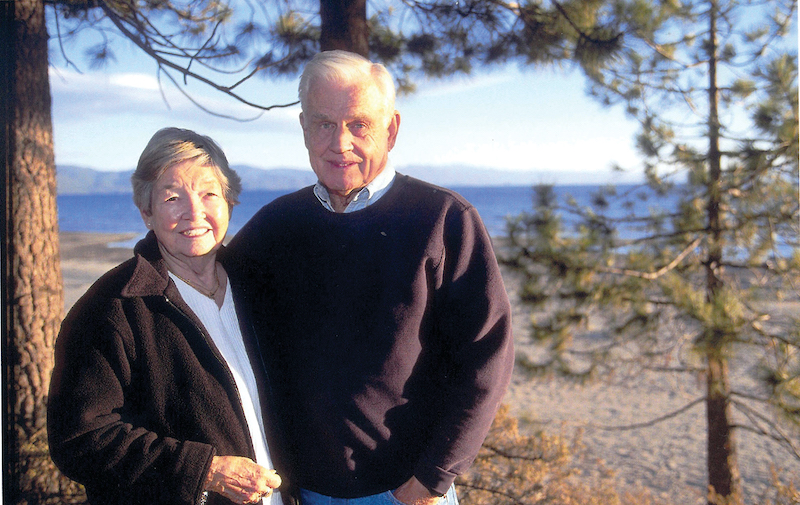

Bud Anderson and his late wife, Ellie, at Lake Tahoe, courtesy photo

Civilian Life

Between combat tours, Anderson reluctantly went to visit Ellie Cosby to offer his condolences after she lost her husband, and Anderson’s best friend, Jack Stacker.

The visit went better than expected, and before returning to combat the two agreed to exchange letters.

Anderson returned from the war on February 1, 1945, and was married less than a month later. He and Ellie had two children and remained happily married for 70 years, until his wife’s death in January 2015.

Ellie’s grandmother purchased two lakefront lots in Kings Beach in 1942, building a summer cabin on one of them. When her grandmother died, the land was transferred to the Andersons, who built a home on the property.

Anderson still enjoys spending time at his second home on Lake Tahoe with his two children (one of whom followed in his father’s footsteps and became a fighter pilot), as well as his four grandchildren and five great grandchildren.

Inspired by one of the greatest American fighter pilots in history, Blake McReynolds, 10, cruises down the street in a mini replica of Bud Anderson’s P-51 Mustang during the 2019 Auburn Veteran’s Day Parade, courtesy photo

Talking about current events and the challenges facing the United States, Anderson draws parallels to the COVID-19 pandemic and World War II, when the whole nation was asked to support the war.

“Our brave young men swarmed to the recruiting stations. Nearly everyone else went to work in the defense industries. The general attitude among the American public then was, ‘Let’s do our part. Let’s get this war over with so we can get back to normal,” says Anderson.

“I believe we’re in a similar situation in that we all need to do our part. We should help our neighbors when possible, remain healthy and work together to get our country back to normal.”

Looking to the future, Anderson says it’s up to the younger generation to steer the nation in the right direction. He advises youth to set ambitious, worthy goals early in life and work hard to achieve them. But also, “Never give up or lose your sense of hope or humor… and don’t take yourself too seriously.”

“We need to get back to basics,” says Anderson. “We shouldn’t give trophies to everyone just for showing up. Awards should be given to those deserving. Children need to know that hard work pays off and awards are earned.”

Closing in on his 100th birthday, Anderson shows no signs of slowing down. When not imparting wisdom to youth, he can be found giving interviews with aviation buffs around the world and attending air shows, still fascinated by the art of flight.

From that kid on a farm who ran outside to look at airplanes flying overhead, Anderson pursued his passion to become a national hero. He is one of the finest fighter pilots who ever flew, a living legend who is proud to have served his country admirably.

And yes, Anderson still dreams about flying around the clouds in his own plane, the same as he did as a young boy.

To learn more about Colonel Clarence E. “Bud” Anderson or to purchase a copy of his book, To Fly and Fight, Memoirs of a Triple Ace, go to www.cebudanderson.com.

Michael Kennedy is a Squaw Valley-based pilot and photojournalist. He is honored to tell the story of a true American hero.

David Armstrong

Posted at 08:36h, 26 JuneGreat story about a great man – thank you!

Jeffrey W Clemens

Posted at 19:03h, 26 November“I thought he (Bud) was the greatest then, I still think he is the greatest now.” Bill Overstreet, 357th Fighter Group, 363rd Fighter Squadron (1921-2013).

David Armstrong

Posted at 00:19h, 28 NovemberYes, he IS.

Greg Gaunt

Posted at 07:21h, 08 DecemberWhen I see Col Anderson, I think of his friend (and mine) and assistant, Kelly Kreeger (RIP), who was instrumental in many of these celebrations of Bud’s achievements and for his unofficial “Super Fan” program which she championed for the young kids. Last night an old friend of his passed away-Chuck Yeager. Blue skies to both Chuck and Kelly and a Merry Christmas to Bud.

Barbara Heiam-Bjørnsen

Posted at 11:51h, 25 MarchI’m so proud of Col. Andersen for his courage and valor to be one of the most important reasons the US won over the evil German’s. I was born in 1951 and heard so many of their stories as I grew up. It made me proud of them and me proud to an American. Ha! In 1956 on my way to our neighborhood fort hidden on a grassy bank up from the Minnehaha Creek, I remember looking down at my PF Flyer athletic shoes with the American flag printed on the back thinking how grateful we were to be alive and living free thanks to those like Col. Bud Andersen that fought for our freedom! And thank you Micheal Kennedy for your photographs and wonderful story of one of our true war heros👍😉

Alex Mund

Posted at 06:12h, 19 MayI am proud to know that what I have enjoyed as a citizen of our great nation is because of men like Col. Anderson. He was humble, faithful and determined and willing to give “his best” in the defense of our country. May we never forget the sacrifice he made in defense of our country! Blue skies and a strong tailwind to you always, Col. Anderson. May the “Old Crow” always fly!

Phil Hunt

Posted at 08:46h, 20 MayFascinating story! Where do we get such men?

Phil Hunt

Posted at 08:51h, 20 MayAs a former Vietnam pilot (USMC), I really appreciated the comments about good eyesight!

Dr Ederich Viviers

Posted at 22:04h, 04 OctoberWhere can I get this picture please it is a photograph that I have seen with a metal cutting at the bottom of the framaed pictur plz?

Dr Ederich Viviers

Posted at 22:05h, 04 OctoberIt is this picture I am reffuring to

“Bud Anderson sits on the wing of his trusty P-51D during World War II, courtesy photo”