27 Jun California’s Lurking Lava

In a state shaped by its explosive past, the eight active volcanoes from Mount Shasta to Salton Buttes pose distant yet significant threats to their local communities, infrastructure and resources

A view of the Lassen Peak eruption from Red Bluff on May 22, 1915, photo by R.E. Stinson, Benjamin F. Loomis Historical Photograph Collection

California is no stranger to natural disasters. Between earthquakes, mudslides, floods and wildfires, the Golden State had been handed the short end of the stick by Mother Nature countless times.

But tremors, tsunamis and wind-whipped flames aren’t the only “acts of God” that make insurance agencies squirm. There is another ominous natural force that some Californians may come face to face with in their lifetime—one that doesn’t get much attention, but whose threat is very real: a volcanic eruption.

The chance of a catastrophic eruption happening may seem remote, but that’s only because the threat is out of sight, out of mind for most people. The reality is that the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) has eight volcanic areas in California on its watch list, including three volcanoes rated as “very high” threats (the highest risk category), and three rated as “high” threats.

These elevated threat ratings correlate to a 16 percent chance that there is a small to moderate volcanic eruption somewhere in California in the next 30 years, according to a 2019 USGS report. In comparison, the 30-year odds of a magnitude 6.7 or greater earthquake along the San Andreas Fault in the Bay Area is thought to be about 22 percent. Given the relatively similar odds, it could be argued that the threat of an eruption in California should receive more recognition, especially considering the damage volcanoes have wreaked on other U.S. states.

The scale of property destruction that occurred during the 2018 Kīlauea volcanic eruption on the island of Hawaii was surreal. Fountains of lava (molten rock above ground) spewed from cracks in paved roads and swallowed entire subdivisions. Some 700 homes were reduced to ash in a matter of days. Could a similar scenario play out in California one day? Very unlikely, but it’s not out of the question.

The state’s topography was shaped by volcanic activity over hundreds of millions of years. The granite bedrock of the Sierra Nevada was created by volcanoes eons ago, and more recent volcanic activity helped form Lake Tahoe and dozens of other notable terrain features that we live and recreate upon today. So if an active volcano like Mount Shasta blew its top, and an unstoppable lava flow mowed over the surrounding towns like in Hawaii, it would not be geologically unprecedented.

But of all the things to worry about in life, getting incinerated by lava should not be one of them. Volcanoes don’t spontaneously erupt like an earthquake. Eruptions give warning signs and modern monitoring systems will alert all those in hazard areas long before any lava starts flowing. The only eruption prep needed is a basic awareness of the state’s active volcanic areas and, if curious, an understanding of how historic volcanic activity shaped parts of California.

Lassen Peak erupts on June 14, 1914. The three-year eruption began in May 1914, peaked in May 1915 and continued until June 1917, photo by B.F. Loomis, Benjamin F. Loomis Historical Photograph Collection

Monitoring the Magma

There are over 500 active above-ground volcanoes in the world today. To be considered active, a volcano must have erupted in the last 10,000 years, and magma (molten rock below ground) must still reside underneath the volcano in what’s called a magma chamber. An active volcano that is not currently erupting is considered a dormant volcano, and a volcano that no longer has any magma in its magma chamber is considered extinct.

The eight “watch list” volcanic areas in California are distributed somewhat evenly throughout the state. They include Medicine Lake Volcano, Mount Shasta and Lassen Volcanic Center in Northern California; Clear Lake Volcanic Field just north of the Bay Area; Long Valley Volcanic Region on the east side of the Sierra near Mammoth Lakes; and Coso Volcanic Field, Ubehebe Craters and Salton Buttes in Southern California.

All but one of these volcanoes is considered active, and all eight have erupted in the last 10,000 years—the scientific benchmark for a “young” volcano.

The youngest volcano in California is Lassen Peak, which famously erupted from 1915–1917. This eruption episode was highlighted by an explosion in 1915 that shot ash 30,000 feet high and spewed a devastating river of hot ash, gas and rock called a pyroclastic flow 4 miles down the northeast slope of the mountain.

Over 200,000 people live in the volcanic hazard zones surrounding these eight watch-list volcanic areas. The USGS assigns a threat rating for each volcano based on a combination of the perceived destructive force of the volcano, the exposure of communities, infrastructure and resources to the volcanic hazards, and the probability of an eruption occurring. The volcanos with the highest threat ratings are both the most likely to erupt and the most hazardous to people, property and transportation lines.

The California Volcano Observatory (CalVO) is the federal agency in charge of monitoring in-state volcanic activity and making sure no one gets caught by surprise if the lava starts flowing. CalVO is one of five U.S. volcano observatories operated by the USGS. Located in Menlo Park, the agency consists of a team of scientists who research each volcanic area’s historic “personality” with an aim to understand how the volcano might react if it were to ever get testy again.

Lassen Peak’s Devastated Area was created by a pyroclastic flow in May 1915, photo by Michael Clynne, U.S. Geological Survey

Dr. Jessica Ball is CalVO’s volcano hazard assessment and communication specialist. Ball is here to assure California residents that an eruption will never sneak up on CalVO.

“That’s the one advantage of volcanoes as far as natural disasters go: They tend to warn us about what they might do,” says Ball. “There are examples of where volcanoes have erupted very quickly by geologic standards, but those types of eruptions are extremely rare, and that’s not the kind of volcanoes we have in California.”

To stay abreast of even minuscule changes to the land in a volcanic area, CalVO has installed sophisticated monitoring equipment at all the active volcanoes in the state. These instruments can sense earthquakes, changes in topography and increasing gas emissions.

“Volcanic events are always preceded by swarms of earthquakes,” says Ball. “So our first line of defense is a seismometer that detects if the ground is shaking because magma is moving through it. When magma rises to the surface of the earth it breaks rock in its path, and it’s those little snaps of rock that we can sense with the seismometer.”

The second type of sensor employed by CalVO is an incredibly precise GPS system that can detect if the ground in a volcanic area is changing shape within a few centimeters or even millimeters.

“The reason we watch how the ground changes shape is because magma moving into a volcano has to displace what is already there,” says Ball. “The ground under a volcano is not hollow and magma chambers are not big open areas that refill like a pipe. A magma chamber is more like a bunch of cracks or thin spaces, so when magma moves into a volcano it forces the ground to deform.”

CalVO also monitors gas discharge at volcano sites. Many dormant volcanoes constantly release gas and steam, but when a volcano is getting ready to erupt, gas discharge levels increase dramatically. The steaming ground and gurgling pools in the Bumpass Hell area of Lassen Volcanic National Park and the sulfur smell near the summit of Mount Shasta are both examples of dormant volcanoes releasing gasses emanating from magma percolating deep below the ground.

Mount Shasta consists of four overlapping volcanic cones, including Shastina, a distinct satellite cone west of the main summit. Shasta’s last known eruption was around 1250 A.D., iStock photo / Skyhobo

The Rowdy Ring of Fire

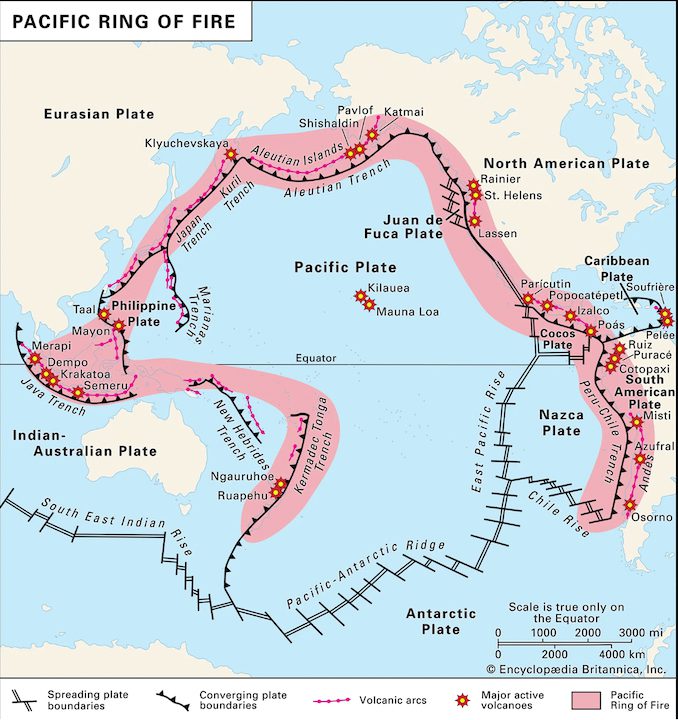

Northern California’s three volcanoes are geologically unique compared to the five volcanoes located farther south. Medicine Lake Volcano, Mount Shasta and Lassen Volcanic Center are part of the Cascade Volcanic Arc, a grouping of about 20 major volcanoes found between Vancouver Island, British Columbia, and Northern California that are part of the Pacific Ring of Fire.

The Ring of Fire is a 25,000-mile-long horseshoe-shaped path that traces the rim of the Pacific Ocean. The Ring of Fire is home to 75 percent of the world’s volcanoes and the four largest volcanic eruptions in the last 10,000 years. The intersection of several tectonic plates along this path creates prime conditions for volcanic activity. When tectonic plates collide, one plate typically slides under the other in a process called subduction. Subduction causes rock to melt and turn into magma. The magma then slowly pushes to the earth’s surface, and when the pressure of the magma builds up enough in one area, a volcanic eruption occurs.

Three of California’s volcanoes—Mount Shasta, Lassen Peak and Medicine Lake Volcano—are part of the Pacific Ring of Fire, image courtesy Encyclopedia Britannica, Inc.

While all three of California’s Ring of Fire volcanoes have erupted in the last 3,000 years, none of them currently show any signs of erupting soon. This is good news, as an eruption’s threat to communities, utility infrastructure and transportation lines in Northern California is among the highest in the state. For this reason, the USGS assigns “very high” threat ratings to Shasta and Lassen, and a “high” threat rating to Medicine Lake Volcano.

“There is quite a bit that stands to be damaged if Mount Shasta erupts,” says Ball. “There are several towns very close to it and the I-5 transportation corridor is right there.”

Over 100,000 people live in the potential hazard zone surrounding Mount Shasta. Only 10,000 live in Lassen’s hazard zone, but that’s not the only concern if Lassen were to erupt, says Ball.

“Lassen is less of a threat than Shasta in terms of people not being near it, but one of the hazards we worry about with Lassen and Shasta is that they are smack dab in the middle of several major air traffic routes,” she says. “An eruption could be a major disruption to transportation on the West Coast, which would have cascading impacts nationwide.”

Shasta and Lassen are also near California’s largest water reservoirs—one of which, Shasta Lake, accounts for over 15 percent of the state’s water supply. If either Shasta or Lassen were to erupt, and cover these reservoirs in ash, the water supply for much of the state would be contaminated.

Adding to the potential peril of an eruption, ash and high-voltage power lines don’t mix. If volcanic ash covers electrical or telecommunications lines, it can cause significant damage and widespread outages. Nearly 2,000 miles of electrical transmission lines supplying power from Washington, Oregon and Canada to millions of homes in California run through the hazard zones of Shasta, Lassen and Medicine Lake Volcano.

Despite the significant threat, CalVO feels the likelihood of any of these three volcanoes erupting in the next 30 years is quite low. In its 2019 hazard assessment report, CalVO estimates the chance of eruption to be 0.5 percent for Lassen, 1 percent for the Medicine Lake Volcano and 3.5 percent for Shasta. And although Mount Shasta has slightly higher odds, Ball is not concerned.

“Right at this moment I would not say that Shasta is going to be the next volcano to erupt in California,” says Ball. “We know that Shasta is a young and still active volcano, but we don’t currently see any indications that there is any magma near the surface or moving into its plumbing system.”

Paoha Island, the biggest of Mono Lake’s three islands, was formed by volcanic uplift only 250 years ago. Rising magma pushed up the land 200 feet but did not break the earth’s surface, photo by Seth Lightcap

Hazards in Long Valley

On May 18, 1980, the deadliest volcanic event in U.S. history occurred when Mount St. Helens erupted in Washington. Fifty-seven people were killed, 200 homes were destroyed and over 200 miles of highway was obliterated in the violent eruption.

Barely a week later, on May 25, a series of magnitude 6 earthquakes rocked the Long Valley Volcanic Region, a well-documented volcanic area on the east side of the Sierra near Mammoth Mountain and the town of Mammoth Lakes. Still reeling from the Mount St. Helens blast, the USGS immediately began assessing if the Long Valley was also about to erupt.

What they found was that a dome-like swelling in the center of the region had risen a foot in the last year. Coupled with the earthquakes, the ground deformation was an obvious sign that new magma was rising into the area. Fortunately, no eruptions or further strong earthquakes occurred after the initial swarm. The shakes and uplift were only a tease of the region’s potential for volcanic unrest. Not that it was ever questioned.

Hundreds of eruptions over the last 4 million years created the many volcanic terrain features found in the Long Valley region. A massive eruption 800,000 years ago formed the Long Valley Caldera (a 10-by-20-mile collapsed basin in the center of the zone), while Mammoth Mountain ski resort is a cluster of overlapping lava domes formed by eruptions 50,000–100,000 years ago. The most recent eruptions in the region occurred north of Mammoth near Mono Lake, where a series of eruptions approximately 700 years ago formed the Inyo and Mono Craters, and a substantial magma uplift only 300 years ago formed Paoha Island in the middle of Mono Lake.

The Horseshoe Lake tree kill zone on the south side of Mammoth Mountain was caused by high concentrations of CO2 gas released into the soil from an active magma chamber underneath the ski resort, photo by Seth Lightcap

After the unrest in 1980, the USGS installed an extensive monitoring system in the Long Valley that now consists of over 20 seismometers, 16 GPS sensors and several gas emissions detectors. For the last 25 years, Stuart Wilkinson, a physical science technician employed by CalVO, has maintained the instruments.

“The main changes I’ve seen in the last 25 years of monitoring the Long Valley are the increased carbon dioxide gas emissions in the Horseshoe Lake area behind Mammoth Mountain,” says Wilkinson. “We’ve also had some swarms of earthquakes, but nothing too concerning or alarming. The ground uplift across the Long Valley Caldera in the last couple decades has also been relatively nominal.”

No signs point to an eruption happening soon in the Long Valley, but if one did occur, it would pose a serious threat to the 60,000 people who live in the region, as well as the 1,200 planes a day that fly over it. Eruptions of the Inyo and Mono Craters in the last 600 years covered the Mammoth Lakes area in several inches of ash and released fiery pyroclastic flows that extended more than 5 miles.

Based on these historic eruptions, CalVo assigns a threat rating of “very high” for the Long Valley Caldera, “high” for Mono Craters and “moderate” for Mammoth Mountain. CalVO and local government and law enforcement agencies have also prepared a comprehensive emergency plan in the event of an eruption.

“We’ve done tabletop exercises based on the most likely scenario we would see in the Long Valley,” says Ball. “An eruption would begin with earthquakes for weeks or maybe even months, then we’d slowly start to see more gas, and eventually a fissure would open up with a few small explosions, but mainly just a lava flow. By that point we would have notified all the public officials about the possibilities of what might happen, and they would have enough information to make decisions about public safety and any potential evacuations.”

In the last 5,000 years, the Long Valley region has experienced an eruption every 250 to 700 years. This correlates to about a 2.5 percent chance of an eruption in the next 10 years and about a 22.5 percent chance in the next 100 years. Wilkinson is reluctant to guess where or when the next eruption in the region will occur, but he suggests it will likely echo the most recent eruptions in the area.

“It’s very hard to say where the next eruption might be, but if we use the past as a key to the future, what we might expect is that there would be a small eruption in the Mono Craters, but not anything large or catastrophic,” he says.

Mount Konocti, a volcano that last erupted 11,000 years ago, rises above the south shore of Clear Lake, iStock photo / James Cross

Don’t Count Out Clear Lake

Though Bay Area residents may rightfully worry more about earthquakes than a volcanic eruption, there is an active volcanic area in their midst. The Clear Lake Volcanic Field is located only 90 miles north of San Francisco and includes both its namesake lake and the town of Clear Lake.

CalVO assigns the Clear Lake Volcanic Field a “high” threat rating because magma is present under the area and the region is home to nearly 20,000 people. Clear Lake is known for its steam vents, hot springs and geothermal power plants, which are all telling signs of lingering bodies of magma. As for the last eruption that occurred at Clear Lake, it’s anyone’s guess.

“We don’t currently have a great handle on when the last eruptions in Clear Lake occurred or how long they lasted,” says Ball. “So Clear Lake is threatening because the craters are all in populated areas, and we are still learning their eruption history.”

There is potential cultural evidence of Clear Lake’s last eruption as Native American tribes have inhabited the region for nearly 14,000 years. Local tribal mythology includes stories of fights between giants and deities, fire on the mountaintops and rocks coming from the air, suggesting that the native inhabitants witnessed eruptions.

Without a solid grasp on Clear Lake’s volcanic history, CalVO has not offered any odds on the chance of a future eruption—only an acknowledgment that volcanic unrest in the region remains possible.

The Salton Buttes are lava domes formed around 2,000 years ago that still contain liquid magma underneath, photo courtesy U.S. Geological Survey

CalVO has the same perspective on the Salton Buttes, a volcanic area on the southeast shore of the Salton Sea about 90 miles southeast of Palm Springs. CalVO assigns the Salton Buttes a “high” threat rating, but the agency does not know enough about the region’s volcanic history to confidently predict the likelihood of another eruption.

The Salton Buttes area is sparsely populated and few transportation or utility lines cross the volcano’s hazard area, but the region is very geothermically and seismically active, which contributes to the threat rating, says Ball.

“The fact that the Salton Buttes are in close proximity to several fault systems that are seismically active is one of the reasons that we consider this area a high threat,” she says. “It’s a possibility that an earthquake unrelated to volcanic activity could open up a pathway for magma to come to the surface.”

The Coso Volcanic Field and the Ubehebe Craters are the other two volcanic areas on CalVO’s watch list. Both are located in remote areas of Inyo County and are not close to any communities. CalVO assigns a “moderate” threat rating to both areas because although they pose less threat to populations, research indicates they both meet watch list criteria.

While it remains uncertain how long ago the Coso Volcanic Field last erupted, CalVO has determined that there is still magma below its surface. The opposite is true for the Ubehebe Craters, where CalVO’s research suggests the last eruption was only 2,000 years ago, but no evidence suggests that magma still resides under the area.

Volcanic activity on the northeast shore of Lake Tahoe around 2.3 million years ago dammed the Truckee River and formed the basalt columns of Twin Crags, photo by Seth Lightcap

Will Lake Tahoe Ever Blow?

Students of Lake Tahoe’s natural history know that volcanism played a role in shaping the Tahoe Basin. Lake Tahoe is not a crater lake that formed from the collapse of a volcano, however.

The lake was created about 3.7 million years ago by a tectonic process called block faulting. As the Sierra Nevada block rose to the west and the Carson Range block rose to the east, a trough formed between the blocks. The trough slowly filled with water from rain and snowmelt, initially creating a shallow lake. Then around 2 million years ago, volcanic activity near present-day Tahoe City sped up the filling process.

Several periods of small volcanic eruptions and subsequent lava flows dammed the Truckee River, which was and still is Lake Tahoe’s only outlet. The lava rock dams caused the lake to fill beyond its current elevation. Evidence of these volcanic eruptions can be seen in the Truckee River canyon just outside of Tahoe City. The basalt columns of the Twin Crags rock climbing area and the craggy Thunder Cliffs across from Alpine Meadows Road are two of these historic dam sites. At one point the level of Lake Tahoe was around 500 feet higher, before a million years of water erosion ate through the dams and drained the lake to its modern-day level.

Knowing volcanic activity helped create Lake Tahoe, is there any possibility of a future eruption in the Tahoe Basin? Not a chance, says Western Nevada College professor Dr. Winnie Kortemeier, who is an expert on volcanism in the Tahoe region.

“Thunder Cliffs is the youngest volcanic rock we have dated in the Tahoe Basin, and that rock is around 940,000 years old,” says Kortemeier. “The magma chamber that created those periods of eruptions is extinct, so we don’t have to worry about it.”

But that’s not to say magma has completely left the Tahoe area, Kortemeier notes.

“In the fall of 2003, a swarm of 1,600 micro earthquakes were felt in North Lake Tahoe,” says Kortemeier. “Researchers at UNR determined that these micro quakes were caused by magma moving along a fault line 25 to 30 kilometers below the ground. So there is still magma under Tahoe. It’s just really, really deep.”

The ancient volcanic areas that helped form Lake Tahoe are also considered long extinct by CalVO, which does not monitor the Tahoe region.

Fear Not, Californians

While a 16 percent chance that a volcanic eruption happens in California in the next 30 years is not insignificant odds, the robust monitoring systems in place at all the volcanic areas guarantee CalVO is going to provide plenty of time to get out of harm’s way should any unrest begin. Residents can also rest easy knowing that a volcanic eruption is a covered peril in most standard homeowners insurance policies.

For those who do live in a volcanic hazard zone, Ball suggests staying informed, but not stressing about it.

“Living in a volcanic hazard zone is very similar to living in a zone that’s very close to a major fault line, or in a zone that could have wildfires,” says Ball. “You might not ever experience a major earthquake in your lifetime, but you want to know what to do if there was one. Same goes for a volcanic eruption.

“You just don’t want to be there when it’s happening,” she adds. “In the event of any volcanic eruption, the USGS would work with all of our partner agencies to help make the best decisions to keep people safe. And that might not involve evacuations or shutting down cities. It might just involve closing a park or wilderness area, just like they do during wildfires. We want people to be aware of what the hazards might be, but not be afraid.”

Seth Lightcap is an Olympic Valley–based writer, photographer and avid explorer of Sierra rock, snow and trail. See more of his stories at www.sethlightcap.com.

No Comments