28 Nov Chronicles of an Acclaimed Cameraman

How a Southern California surfer turned Tahoe ski bum became a pioneer of outdoor sports photography—then quit the profession to start a new life on the other side of the world

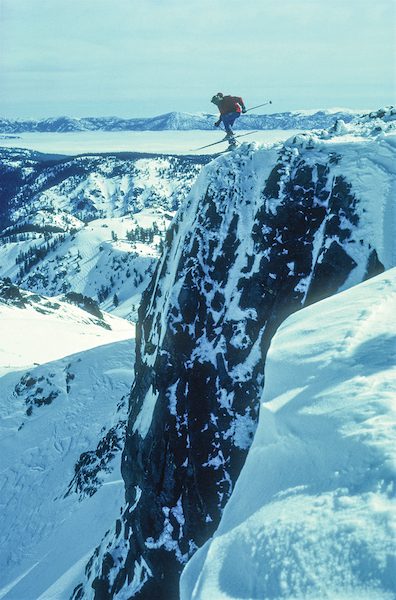

Scot Schmidt steps off the Palisades and into Tahoe lore

Larry Prosor isn’t one to glamorize the past or vilify the future, tempting as it may be for someone who built a career on the cresting wave of extreme sports photography in what was arguably the golden era of Tahoe, only to watch it flounder in the post-9/11 morass of digital cameras, market insolvency and oversaturation.

These days, the waves Prosor rides are the ones just beyond the home he remodeled in the Western Bay of Plenty, in his adopted New Zealand. He likes them clean and small, ideal for a longboard, and he makes the short commute from his house as often as he can.

“I’m all about the glide and having fun,” he says on a rainy late morning from his home overlooking the sheltered bay below.

Though he recently bought a digital camera and resumed taking pictures after a yearslong break from the craft, his preferred cameras now are the public access ones aimed at his two favorite surf breaks, the names of which he withholds out of respect for the local community.

Which is not to say he has abandoned his former trade. Prosor keeps a storage unit for the 200,000 film images he saved from that golden era in Tahoe and the greater Sierra Nevada, and he is in the process of digitizing them. Many images he has not seen in years. Some, including the final rolls he shot before moving to New Zealand in 2004, he has never seen. He plans to share the best of these images on his website as they become available.

Of the fraught cultural debate in some circles between film and digital photography, he is circumspect and diplomatic: “They both have pluses and minuses,” he says. “I’m an old-school dinosaur, but I’m pretty schooled up on what’s new. I’ve embraced digital photography.”

Prosor stepped away from the profession near the turn of the century, but he still thinks in light and frames: the passage of clouds over pastureland, late afternoon sun diffused through the forest canopy, a paintbrush dusk reflected on the backs of breaking waves. When he started shooting again with his digital camera, the learning curve, such as it was, was merely technical. The art of the image never left him.

Today, at 68, taking pictures is mostly a hobby, though he did get his commercial license to lead custom photo tours around the island—it’s hard to turn down the tourist dollar. But Prosor isn’t really in it for the money anymore. “Chasing the dollar with photography is different from just shooting for pleasure,” he says. In his semi-retirement, shooting for pleasure, on a digital camera, on the seashores and hillsides of New Zealand, is about as good as it gets.

Mahia Peninsula on the North Island of New Zealand at sunset

He will, on occasion, aim his lens toward the towering peaks near his home. The mountains don’t call to him like they used to, though, and he is content to enjoy them through his viewfinder.

Waking before sunrise, trekking all morning through fresh snow and snapping future cover photos is an activity from a past life, one that now lives mostly in film negatives in a storage unit, local retrospectives (like the one recently held at the River Ranch Lodge) and magazine lore.

“I don’t ski much anymore or get in the snow unless someone pays me,” Prosor says.

But in his younger days, when both he and the “extreme sports” scene in Tahoe were developing in tandem, few were better at hauling a camera up the side of a mountain to capture that one timeless frame that would inspire children to ski, photographers to leave the city and entire outdoor industries to reorient their marketing campaigns.

As a kid, Prosor never saw any of this coming. It was just the wave he got on.

Mountains of Opportunity

When you grow up surfing in late 1960s and early ’70s Southern California, you don’t think about what’s next: You’ve already made it. But when Prosor graduated high school in Palos Verdes in 1974, he had a crisis of identity. His friends were going to Chico State, but he didn’t know what a degree would do for him any more than staying and surfing his life away, earning money working odd jobs.

“I was in limbo after high school,” he says. “I didn’t know exactly what I wanted.”

From left: Ron Bell, Larry Prosor, Chris Smardivich and Bob Bisesto at the base of KT 22. “I’ve got Scott boots, which leaves me guessing it’s 1979 or ’80,” says Prosor

Prosor’s grandfather was a lighting director for ABC, his father, divorced and living in LA, was a stagehand, and his mother had appeared in movies as an infant, including Gone With the Wind. But the first bug to bite him in sunny Southern California was not in Hollywood, but in the San Bernardino Mountains, where, at 8 years old, his aunt first strapped him into leather rental boots, long skis and a rope tow in what he recalls as blizzard conditions. He was hooked.

So, when friends at Chico State told him of a job opening as caretaker for the school’s ski club, he called the president himself, landed an interview and drove the 12 hours in his Volkswagen Bug to accept the position in person. Shortly after, he was living in Chico State’s ski club cabin on the West Shore of Lake Tahoe, skiing 110 days a year and watching, bemused, as the smog of his old life lifted.

He got into yoga. He learned about processed foods. He met like-minded people—athletes, artists, activists. He upgraded his grandfather’s hand-me-down 35-millimeter camera for a used Canon F1, complete with a range of lenses. He started shooting.

“I felt like I had a good knack for it without trying too hard,” he says. But he wanted to try harder. Using money he earned as a drywall taper in the Tahoe construction boom, Prosor added a 16mm camera to his arsenal, with the idea of making films.

“My goal was to give my version of Warren Miller,” he says, citing the iconic ski filmmaker. “But it was sucking up so much of my hard-earned money that I started making phone calls.”

Glen Plake takes to the air during a photo shoot in the Eastern Sierra in the early 1990s. The image would become a feature ad for No Fear

One of the calls landed Prosor a meeting with a private donor willing to loan him a million dollars based entirely on the strength of his slideshow.

“That was a lot of money dangling in front of me,” Prosor says. “But it was a huge commitment, so I ended up backing out. From there, I decided to remain committed to photography.”

Renewed in his passion to focus on still images, Prosor doubled down. Summers in the late 1970s at what is now Palisades Tahoe ski resort were spent scouting ridges and peaks that would, in a few short months, become the perfect tableau down which his buddies-turned-models would launch themselves, long hair streaming behind, primary-color jumpsuits and matching goggles reflecting the snowy steeps.

Those early years were unstructured, uncompetitive and unprofessional, which is not to say Tahoe’s trailblazing action-sport photographers—including the likes of a young Hank deVre, among other talented shooters—didn’t put in their work. It’s just that nobody imagined there would become a capitalist demand for the flights and fancies of a roving pack of 20-somethings playing in the snow.

The main outlet for Prosor and his photographer friends was a semi-regular slideshow at a friend’s house, where a great shot was a great shot, no matter who took it. Hang with your buddies, catch a fresh dose of inspiration, then hit the slopes and do it all again.

‘A Match Made in Heaven’

As the quality of the pictures improved, so, too, did the skiing, in a feedback loop of heightening perfection and audacity, the apotheosis of which was the arrival of a downhill racer from Montana named Scot Schmidt.

Schmidt wasn’t crazy, as some would claim, nor was he a daredevil, a label he resists. He was just a better skier than pretty much everyone.

Scot Schmidt sporting North Face Steep Tech on the back side of Mount Baldy in Southern California

“I had just arrived in Sq**w Valley (now Palisades Tahoe), and I got a job working as a ski tech,” Schmidt says. “My manager liked the way I skied, and he told Larry, ‘You gotta take some pictures of this kid from Montana. He’s really going for it.”

Prosor gravitated to Schmidt right away, photographing him first for fun, and then because, beneath his small-town ski bum presentation, a star was waiting to emerge.

“He was pretty ragtag in his sweatpants and sweatshirt,” Prosor recalls of Schmidt’s early days on the mountain. “I dressed him up a little for photos.”

With the jacket off his own back.

“North Face had just come out with those really heavy-duty Gore-Tex pullover anoraks,” recalls Schmidt, who arrived by bus to the resort’s parking lot with so little money that he stashed his gear in some nearby bushes and slept in an abandoned building for a few days.

“They were the latest and greatest,” he adds. “I saved up for months to buy one. My mistake was I bought the blue one. Larry bought the red one. After working together a few times we realized blue doesn’t work, especially when you’re flying through the blue sky, so, I’d wear his red jacket for the day and he’d wear my blue jacket, and at the end of the day we switched back.”

The constraints of the budget shoot proved trivial for Prosor and Schmidt, whose work together with that bright red anorak resulted in photos worthy of seasoned professionals, not two broke buddies playing with light and speed on Tahoe cliffs. Photos that would help define an era of action sports photography in Tahoe and beyond. Photos that would end up on the desk of Powder Magazine in Dana Point, hand-delivered by Prosor after driving 12 hours with what he knew to be a photographic jackpot.

There in the office, before editors he revered, Prosor played it cool.

“I walked into Powder Magazine and they said, ‘What do you have?’”

Prosor opened his portfolio and flipped through his photos, each more dazzling than the last. “Their jaws dropped,” he says.

Scot Schmidt skis a picture-perfect line in Blue River, British Columbia, in what would become the cover of K2’s 1994-95 catalog

What he had would become an iconic nine-page photo feature with a centerfold—Schmidt in red seemingly falling off the face of the earth. Until then, even within the hallowed pages of Powder, nobody had seen its equal in print. Neither the technical and aerial brilliance of Schmidt, nor the vast wonderland that is the Tahoe backcountry. The symbiosis of the two—skier and slope—seemed less like the “man conquers mountain” narratives of old and more like the emergence of a new species.

“I still don’t know other resorts like Sq**w Valley,” Schmidt says. “It has very unique terrain—ridges, cornices, cliffs and runouts that other resorts don’t have. You can go big and fast. It was the perfect place to showcase that kind of skiing.”

And the photo feature was the perfect showcase. Powder wanted more. Warren Miller called and wanted more. Everyone wanted more.

“That was the big launch,” Prosor recalls.

“That changed everything for me,” says Schmidt. “Practically overnight. I was focused on my racing, but I just didn’t have the dollars or bandwidth to keep chasing it. All of a sudden, here was something new, and it was something I could do.

“Film and photography,” Schmidt adds with a tone of amazement. “I had no intentions of going that route; it just happened. Film and photography took racing out of the equation for me.”

In the coming years, Schmidt would go on to star in dozens of ski films, develop products with The North Face, get inducted in the U.S. Ski & Snowboard Hall of Fame and serve as ski ambassador for the Yellowstone Club, where he remains today, skiing more than 100 days a year.

He shares much of the credit for his remarkable career with Prosor.

“He was starting out as a ski photographer, and he was one of the first,” Schmidt says. “I had never met a professional ski photographer or even knew there was such a thing as a professional ski photographer. He carved that out.

“We were a match made in heaven,” Schmidt adds. “The right time and the right place.”

Carving Out a Career

That sense of timing never failed Prosor. The same wave that led him to the offices of Powder Magazine with a genre-defining portfolio of images took him next to Taos, New Mexico, where he developed relationships on the mountains that would change his life.

Scot Schmidt on Mount Shasta during a 1989 spec shoot with Rob and Eric DesLauriers and Jim and Bonnie Zellers

“I was bouncing around the western United States with my meager portfolio to ski for free and take photos,” Prosor says of the early 1980s. “A lot of doors were starting to open.”

In Taos, he discovered that mountain management was willing to hand him the figurative key to the kingdom: early access with the patrol team.

“I’d been based in Sq**w for five years, and it was hard to get management at the time to cooperate at any level,” Prosor recalls. “Taos was the first, and those guys were great.”

Not only did resort management allow him to join morning patrols, they also invited local ski instructors to serve as models.

“I just followed directions, and everything worked out perfectly,” Prosor says. “That was the big ‘aha’ moment. I always followed the plan based on the morning meetings, tried not to piss anyone off, and that allowed me to be first up with the crew. By the time the public, and my competition, got on the lifts, I was done. I’d have eight or 10 rolls in the bag and just go off freeskiing.”

Prosor continued this system throughout his road trip of the Mountain West, perfecting it as he went, developing his reputation with ski patrol and mountain management, and continuing to build his burgeoning portfolio.

It was on this very road trip, in Sun Valley, Idaho, that Prosor ruined the shot of, and received career counseling from, legendary photographer of the American West David Stoecklein, who was in the middle of his own shoot on the slopes.

“You’re in my shot!” Prosor recalls a man yelling at him and his friend Dave Zischke, who were shooting on the same run.

As Stoecklein marched down to confront the pair, he recognized Prosor from his work with Powder, as well as an image for a Sports Illustrated calendar of a cowboy on a bronco—western themes that Stoecklein himself would later explore with great success. The mood on the mountain immediately shifted.

Temple Cunningham with a cliff drop on the east side of Mount Cook in New Zealand, circa 1996

“He invited me back to his office and told me how I could make a living doing this,” Prosor remembers. “He was very gracious and showed me his work.”

Work that included a lucrative publishing business of postcards and calendars, an activity he encouraged Prosor to consider. By the time Prosor and Zischke made it back to Tahoe, a stack of postcards from Stoecklein in the car and his parting words, ‘Tahoe has lousy postcards’ rattling in their brains, the two had agreed to launch a publishing line together.

Fine Line Productions marked the formal beginning of a career in images that would continue to grow and expand throughout the rest of the 1980s and ’90s.

“I was making a somewhat steady stream of income from my photography in the early ’80s but had to keep my second job as a drywall taper to keep the bills paid,” Prosor says. “In 1990, I quit drywall entirely and was able to pay the bills with just photography.”

Reflecting on that flourishing time in his career, Prosor credits his connections from outdoor retailer shows and his work with top brands like The North Face, K2, Patagonia, Warren Miller and Rip Curl. He also took advantage of new opportunities with booming outdoor sports such as mountain biking, kayaking, rock climbing and—of course—skiing.

“The ski industry at the time had a fair amount of money pumping through it with advertising and magazines,” Prosor says. “I rode that wave and started shooting a lot. In my peak years, I was spending about $25,000 on film and processing just to keep it going.”

‘A Time to Let Go’

By the late 1990s, Prosor’s wave was a little less glassy, a little more turbulent. Things were changing, and not for the better. The development of digital cameras, the saturation of photographers, the rise of stock photo agencies (the “race to the bottom,” as Prosor calls it) and, horribly, in what he views as the last straw, the fall of the World Trade Center towers in 2001.

Following the terrorist attacks, for the first time in years, perhaps decades, Prosor felt unsteady on his wave. He looked with fear at the horizon for what might be barreling down on him. He had no answers.

Raglan, New Zealand’s top surfing destination

Seemingly overnight, tourism dried up, resorts lost revenue, brands slashed budgets, stock photo agencies devalued images and cheap cameras undermined established photographers. Prosor wanted out.

“A lot of things started to change,” he says. “My industry was dying rapidly. I had kids, a mortgage, overhead, liability insurance, and all the bills that kept rolling in. The photo business that I knew prior was never going back. The whole market was changing, and I didn’t want to stay in it.”

Leaving the industry, for Prosor, meant leaving Tahoe, the place that had defined and launched him, and which he, in turn, had helped to define and launch. The work, the people, the mountains—it was all intertwined into one beautiful and complicated game he no longer had the energy to play.

His daughter was already accepted into Montana State, his son was starting high school and there was no better time to start over.

“I want to put roots down somewhere, just to see how it goes, and we can always come back to Truckee,” Prosor remembers thinking in the months after September 11. “People are pulling up roots and putting them down somewhere new every single day. We just have to change our mindset.”

The home the Prosors designed and built above Wainui Beach, Gisborne, New Zealand. The home was completely off the grid with wind generators, PV panels, solar H2O, catch water in tanks from the roofs, propane cooking and backup with woodstove heat

The obvious draw for his family, on a short list that included spots in Baja California Sur, was New Zealand. Prosor and his wife Cindy had visited the island nation as part of their honeymoon, and he had gone back twice for work. Each time he was reminded of how much he needed to be near the ocean, with mountains in proximity. They discussed it at length, came to an agreement and applied for residency.

“We really try to go with the flow,” he says. “If signs point a certain way, we try to pay attention. We got approval for residency on my birthday, and that was a big sign.”

Prosor sold his share of Fine Line Productions to his partner, liquidated his assets in the United States, boxed up their possessions, including his 200,000 film images, and moved with a shipping container to a parcel of virgin land in Gisborne, New Zealand, on the east side of the north island. There, he poured his energy into building an off-the-grid house and restoring his soul from the fallout of the twenty-first century.

“We had enough financial cushion not to stress too much, which was a huge luxury,” Prosor says. “That first year in New Zealand was just a time to let go.”

Life of a Kiwi

In the years that followed, Prosor would develop and manage property, write a novel called Dream Walker, write a screenplay based on the novel and sign an option with one of the producers from The Lord of the Rings series, finally answering the familial call of Hollywood. He would fish and hike and surf. He would leave the home he built in Gisborne and move halfway across the island to the Western Bay of Plenty, where the waves are gentle and consistent.

Cindy Prosor on a ridgetop near her New Zealand home

He would pick up a digital camera—tentatively at first—and find a glimmer of warmth from a once-extinguished flame. He would take stock of his career, in passing moments and in deep pangs of nostalgia. He would watch as some of his early work came back into the social conscious, if not everywhere, at least in Northern California—and especially Tahoe.

“There’s a retro, multigenerational interest in my photography,” Prosor says. “That golden era of sports and photography in Tahoe: the double chairlift, narrow skis, no helmet, colorful clothes, fewer people on the slopes, rock and roll.”

It’s an era that inspires both longing for the past and anxiety for the future, in which the idea of climbing a mountain with a camera, a friend and a bright red anorak and coming back down with a life-changing portfolio of work can feel like an illusion of a lost age, a distant dream increasingly out of reach for those born too late.

“I was really fortunate to have caught that first wave,” says Schmidt. “I didn’t have to compete with anyone for my spot, so to speak. It’s tough to stand out now, because there’s so much talent.”

Cindy and Larry Prosor on the deck of their home, “Tuamotu,” above Wainui Beach, New Zealand

Talent in front of and behind the lens. Talent that proliferated, in part, because of the groundbreaking work of Schmidt and Prosor, two ski bums—kids, really—living their modest dreams in the mountains. All the while, they were unaware of the weight of history, the obsessive love of the craft bordering on fanatical that would forge friendships, launch careers, move magazines, push products and open the slopes to anyone who ever wanted to ski just like Scot Schmidt, or capture it just like Larry Prosor.

Equal parts forefather to and victim of the hordes of photographers in the mountains (amateurs and professionals alike), Prosor remains equanimous. He does, however, allow the occasional note of caution.

“I think people want to back off from digital experiences,” he muses. “We’re at a point of saturation that blows my mind. Electronic clutter that just floats around. If someone whips out their phone and says, ‘Let me show you some photos,’ I automatically cringe. I am disinterested in so much of what’s out there.”

Prosor pauses, gathers his thoughts. “You have to go with the flow,” he adds. “If the surf’s up, I’m going surfing. Thank God for waves.”

Of all the impacts wrought by Prosor and his cohort of fellow athletes and photographers, his most profound is his most personal: a narrow opening in the universe through which the surfer kid from Southern California serendipitously passed, sending him northward, grandfather’s 35-millimeter camera in hand, to the snowcapped peaks of Tahoe and a life that offered what he could never name as a child, but always wanted.

“That shift to Tahoe really solidified that I didn’t want to live a conventional existence,” he says.

Half a century later, staring through his rain-speckled windows over the Western Bay of Plenty—his life anything but conventional—Prosor looks back with gratitude and fondness for the wave that lifted him and carries him still. When the weather breaks, longboard in tow, he’ll head down to his local spot and ride a few good ones.

Michael Rohm is a freelance writer based in Portland, Oregon. After reporting on the life of Larry Prosor, his next byline just might be based in New Zealand.

No Comments