22 Feb Igloos, Ice Palaces and Quinzhees: The Improbable World of Snow Structures

From elaborate hotels to rudimentary survival shelters, dwellings made of ice and snow continue to serve a purpose around the world

Reason number 767 why Tahoe kids are super lucky: We live in a world-class region for building snow forts.

If you grew up in a snowy climate, you probably have fond memories of playing in a snow fort. Maybe you dug a sketchy cave in a plow pile, or perhaps you made a snow castle with an armory of pre-made snowballs at the ready. Either way, days spent in a make-believe city of snow were cherished.

For how fun it is to hang out in a snow fort, and for how many adults love snow too, you might think there would be more options for adults to spend time in adult-sized snow structures. But, alas, this is not the case.

Very few structures on earth are built with snow despite its amazing structural capabilities and insulative properties. The ephemeral nature of snow has a lot to do with that, obviously, and the cold factor, but in the right conditions, and if prepared with the right accouterments, time spent in a snow dwelling can be just as spectacular for an adult as it is for a kid.

All hope for adults is not lost, however. There have been occasions in the past, and there are opportunities in the present, where adults can comfortably surround themselves with walls of frozen water. From ice palaces to ice hotels, and backyard igloos to backcountry snow caves, the potential is out there for adults to spend quality time living in the snow.

So for all those who yearn to return to their snow fort days, let’s explore a few ways humanity has embraced ice and snow structures both historically and in modern times.

The Original Snow Dwelling

The most well-known style of snow structure in the world is without a doubt the igloo. An igloo is a dome-shaped structure made of stacked snow blocks that was invented centuries ago by nomadic Inuit tribes in the Arctic regions of what is now northeast Canada and Greenland.

Traditionally, Inuit families used igloos as semi-permanent housing in the winter months, as well as temporary shelters for hunting trips. Multiple families would build medium-sized igloos close together to make an igloo village that they would occupy for a few months before moving on. Hunters would build small igloos to stay in for a couple of nights while out hunting away from the village.

In a photo from 1924, an Inuit man holds a snow block and snow knife in front of an igloo he’s building for his family, photo by Frank E. Kleinschmidt

To heat the igloos, the Inuit would burn seal fat and wood, and later oil lamps and kerosene stoves. Snow is such an amazing insulator that outside temperatures could be as low as minus-50 degrees Fahrenheit, while inside temperatures warmed by body heat alone ranged from 19 to 50 degrees.

As the Inuit encountered Europeans in the late-1800s, they adopted modern wood frame construction for permanent housing, but the igloo remained a valuable shelter for Inuit hunters through the nineteenth century. Building an igloo was an important skill passed down from father to son as every hunter relied on igloos to survive in the unforgiving Arctic climate.

Joe Karetak is an Inuit who grew up on the shore of the Hudson Bay in the Nunavut territory of Northern Canada. Karetak’s father taught him how to build an igloo in the 1970s on hunting trips when he was a young child.

“Every time we went out hunting, my father and his hunting partner would build an igloo in the evening for us to stay in for the night,” says Karetak. “They made igloos so often that they could build one in a half-hour. One person would cut the blocks while the other put the igloo together.”

Though the concentric block design of igloos looks simple, they are deceivingly challenging to build. Erecting one in a half-hour takes not only well-practiced technique, but also perfect snow, says Karetak.

“You are looking for hard, wind-packed snow that fell in one storm and is all one density,” says Karetak. “Any layers in the snow will make the snow blocks weaker.”

The Inuit traditionally cut out snow blocks using a knife with a foot-long blade and an equally long curved handle. The long handle allowed them to use two hands to make precise cuts. The shape of the first row of blocks is especially important, says Karetak.

“The first row of blocks must be cut so the bottom of the block sits flat and the top of the block has a slight inward angle. If you place the first row of blocks at 90 degrees to the snow surface, you probably won’t be able to finish the top of the igloo.”

Beyond finding the right snow, location is also key to an igloo’s warmth, explains Karetak.

“The permafrost is constantly generating cold, so if you build an igloo on land, it’s very hard to keep any heat inside. The best location to build an igloo is on a frozen lake. The snow on the lake is an insulation layer and the ice underneath always stays the same temperature.”

Most Inuit hunters now use insulated tents on hunting expeditions, but knowing how to build an igloo is still a skill every Inuit hunter needs to have, says Karetak.

“We live in one of the harshest environments around, and in a lifetime of hunting, sooner or later you are going to run into hardship and be forced to build an igloo as an emergency shelter,” he says. “Even if you build one that just covers you, you can survive the night if you get out of the wind and elements.”

Book a Night in an Igloo

While the Inuit traditionally built igloos for their critical functionality, modern-day entrepreneurs in other snowy regions of the world have parlayed the improbability of sleeping in the snow into a profitable novelty. Igloo and ice hotels, where most if not all lodging structures are constructed out of snow and ice, now beckon the adventurous traveler.

The first ice hotel in the world opened in 1990 in the village of Jukkasjärvi, Sweden. Built out of massive ice blocks cut from a frozen river, the Icehotel Jukkasjärvi is still open from December to April and features a bar, restaurant, church and several dozen guest rooms, all decorated with snow sculptures.

Iglu-Dorf Kuhtai is a hotel made out of snow in the Stubai Alps of Austria, photo courtesy www.iglu-dorf.com

Beyond Sweden, there are now well-established ice hotels in Canada, Norway, Finland, Japan and Romania, plus a seasonal hotel chain in the European Alps that operates igloo villages at six ski resorts.

This European ski resort–based igloo hotel business is called Iglu-Dorf. The business was founded in 1996 by Adrian Günter, a Swiss ski instructor who built an igloo on the side of a resort where he was working at the time.

“My colleagues would ask me why I smiled so much when I came to work in the morning,” says Günter. “I would point to my fresh ski tracks coming down the mountain from the igloo I had slept in the night before. They were like, ‘Wow! I want to do that!’ So I started letting friends borrow my sleeping bags and stay in my igloo. The more people heard about it, the more they wanted to try it, which made me realize an igloo hotel could be a good business at a ski resort.”

The first season Iglu-Dorf opened, Günter built three Igloos at one location that could accommodate 15 people a night. Their igloo villages now host a combined 8,500 guests each winter at six locations in Austria, Germany and Switzerland, including Zermatt, Davos, Kuhtai and Gstaad.

For the first six years of operations, Günter and his crew built their igloos using the classic Inuit block construction method. But lacking the perfect snow that the Inuit enjoy, building that many igloos was a massive amount of work. This got Günter thinking about other potential igloo construction methods.

“I was trying to fall asleep in an igloo that I had spent all day building, and I started thinking about how I could build igloos faster,” says Günter. “That’s when the idea popped into my head to try and use a balloon. I reasoned that I could pile snow on the balloon to form the outside structure of the igloo, then deflate the balloon to instantly create the inside space.”

All the rooms at Iglu-Dorf hotels are decorated with intricate snow carvings, photo courtesy www.iglu-dorf.com

After testing the concept with standard-size balloons, Günter had a balloon builder make him a balloon in the shape of a full-size igloo. The balloon method turned out to be a genius idea, as Günter can now build his snow structures much faster and in any shape.

Instead of waiting for natural snowfall, Iglu-Dorf uses snow guns to cover the balloon in a layer of man-made snow. Once the balloon is covered, they dig out the igloo entrance at the balloon’s valve, then deflate the balloon, leaving behind a perfectly shaped room inside.

The temperature inside Iglu-Dorf’s sleeping rooms and restaurants hovers between 28 and 35 degrees Fahrenheit as long as there is good air circulation through the rooms. If the doors are closed, the temperature will climb to above 40 degrees. But even with the doors open, Günter says guests often remark about the cozy temps.

“When it’s 0 degrees outside, and you come inside, you will think, ‘Wow! This is quite warm!’ But the warmth is deceiving,” says Günter. “We recommend guests wear their ski apparel inside the restaurant or the sleeping rooms because the temperature may only be 28 degrees. Wearing jeans and sneakers at that temperature is not fun for too long.”

Sleeping warm is not a worry as they provide guests with minus-40-degree sleeping bags to snuggle into for the night. With the room temperature hovering around 32 degrees, these polar expedition–worthy sleeping bags are overkill, but they guarantee no guests will wake up shivering.

“We don’t want our guests to go home and tell their friends that they were freezing. We want them to say they were sweating in their sleep,” says Günter. “There are also people that have bad circulation, so the super warm bags make sure they stay comfortable at night as well.”

A night spent at an Iglu-Dorf hotel includes dinner and breakfast at a restaurant built with snow, photo courtesy www.iglu-dorf.com

All six Iglu-Dorf locations offer both standard rooms and suites. The standard rooms have shared bathrooms and Jacuzzis, while the suites come with private bathrooms and Jacuzzis. All the rooms are decorated with elaborate snow sculptures.

“At our Zermatt village we have two suites that include a private Jacuzzi with a view of the Matterhorn. These suites are very popular with social media influencers. They all want to sit in the tub and take pictures with the Matterhorn,” says Günter.

A night in the Matterhorn suite costs $1,000 per couple, but less distinguished rooms can be had for a much lower cost. The room price also includes dinner and breakfast at an attached restaurant made from snow. Between the stunning locations, the thrill of sleeping in the snow, and the convenience of waking up on top of the mountain ready to ski, a night spent in an Iglu-Dorf village presents a unique value, says Günter.

“When you step outside your igloo in the evening, you see so many stars it’s scary. You feel like you’re in the middle of the Milky Way,” says Günter. “In our busy lives, it is very easy to forget that you are connected to the universe. Seeing stars like this and sleeping in the snow on top of a mountain helps remind you that you are a part of something bigger.”

Turning an Icicle Into an Ice Palace

An igloo village or ice hotel located at Palisades Tahoe’s High Camp or Heavenly’s Tamarack Lodge might be feasible in December and January, but inevitable warm spells and rainstorms would likely melt away any opportunity to operate such a lodging venture at Lake Tahoe for an entire winter. The closest thing the Tahoe region has ever seen to a public snow structure were the legendary ice palaces built in Truckee in 1895 and from 1913–1915 for the town’s annual winter carnivals.

Truckee’s ice palaces were the brainchild of Charles Fayette McGlashan, a local community leader, author and lawyer who sought to revive Truckee’s depressed economy at the turn of the nineteenth century by establishing the town as a winter sports and recreation destination. At that time, logging and mining opportunities in the region were drying up, and tourists only came to Truckee and Tahoe in the summer months, leaving locals hurting for income in the winter.

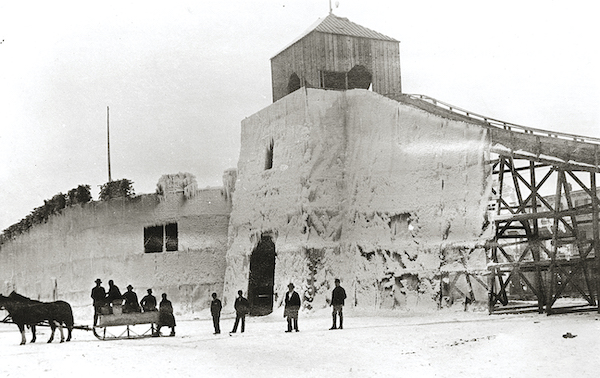

The first Truckee ice palace was built in 1895 and featured an ice rink and a toboggan slide, photo provided by Truckee-Donner Historical Society

McGlashan’s vision was to create a winter carnival in Truckee that would attract tourists from the Bay Area to come visit mid-winter. Inspired by the Montreal winter carnival that featured a castle-like ice palace, McGlashan wanted the centerpiece attraction of Truckee’s winter carnival to be a sprawling ice palace that housed an ice-skating rink, live music, concessions and a toboggan run.

McGlashan’s first move in convincing fellow Truckee businessmen that they could host a winter carnival centered around an ice palace was to build a 60-foot-tall icicle structure at his house overlooking downtown in the winter of 1894. Starting with a cone-shaped wood frame wrapped in chicken wire, McGlashan sprayed water on the wire frame every night until the structure was coated in a thick layer of ice. With a powerful light beaming down on the icicle from a nearby flagpole, the glimmering tower of ice caught the attention of anyone passing through Truckee at night.

The eye-catching icicle sunk the hook for McGlashan, as the town agreed to host a winter carnival and build an ice palace the next winter. This first ice palace was built in the heart of downtown using the same wood-and-wire-framed construction methods as McGlashan’s icicle. Upon completion, the palace was 700 feet long and 200 feet wide with walls 50 feet high. Inside the palace walls was an oval ice-skating rink, while a 75-foot tower with a toboggan run dropped from the top.

The palace was a huge hit, as tourists from all over California and Nevada came to Truckee that winter to check out the unique structure and frolic in the snow. Though the ice palace was not rebuilt in subsequent winters, it established Truckee as the first winter carnival destination in the West.

Truckee’s ice palace was resurrected in the winter of 1913–14, when the Truckee Chamber of Commerce made plans to host their biggest winter carnival ever, a month-long party they dubbed “Fiesta Of The Snows.” Festival plans included the construction of a permanent ice palace in the meadow at the west end of South River Street below the current Cottonwood restaurant. The gigantic palace was built with wood and expanded metal that was sprayed with water to form the glimmering ice walls. The palace complex included an ice-skating rink, a dance hall and mile-long toboggan runs that dropped down the adjacent slope to the front of the palace. Colored lights illuminated the palace’s exterior and hundreds of fresh roses were brought in to decorate the interior for its grand-opening celebration in late-December.

The ice palace and winter carnival were a massive success for Truckee and drew a record number of tourists to town that winter. With a permanent structure, the ice palace was rebuilt the following winter and used to host an even bigger winter carnival in 1915, but it did not last long. In June of 1915, the wooden framework of the ice palace caught fire, and while the winter carnival continued to thrive, the ice palace was never rebuilt due to safety concerns.

From Snow Pile to Snow Cave

International ice hotels and one-off structures erected for events are the most grandiose examples of snow structures, but the most common snow shelters in the world are much more humble abodes built by winter camping enthusiasts, backcountry skiers and youth groups.

A quick search on YouTube pulls up dozens of videos from snow shelter builders around the world showcasing their creations. Many take on the challenge of constructing an igloo using the traditional Inuit block construction method, while others opt to build a more rudimentary snow shelter called a “quinzhee” that does not require the perfect snow or building precision of a classical igloo design.

Allison Lightcap prepares to step outside before settling in for a night spent in a quinzhee

Quinzhee is a word of Athabaskan origin, and though it’s unclear which if any native Athabaskan communities traditionally built snow shelters with this technique, the definition of a quinzhee is well established. A quinzhee is an above-ground snow cave that has been hollowed out from a large pile of snow.

Molly Hagbrand, an instructor for the National Outdoor Leadership School (NOLS), has spent more nights sleeping in a quinzhee than most. Hagbrand leads winter backcountry skiing courses for high school and college students and teaches how to build quinzhees on these wilderness courses.

“Quinzhees are inspired by igloos, but they are much faster to build than a traditional block-constructed igloo for most people and snow conditions,” says Hagbrand. “All you need is a flat location and a foot or more of snow on the ground.”

Hagbrand and her students start the quinzhee-building process by piling up snow in a large mound. To make sure the quinzhee will be structurally sound upon excavation, they pack down the snow as they make the pile.

“It’s critical to work-harden the snow pile by walking around on it and pounding it with your shovel,” says Hagbrand. “This compacts the snow and allows you to dig into the pile without the walls or roof collapsing.”

For a quinzhee that will comfortably sleep three to four people, Hagbrand and her students stack up a snow pile that is around 10 feet in diameter and 6 feet tall. Once the pile is made, they let it sit for an hour to allow the snow crystals to bond together. While they wait for the pile to harden, they insert 18- to 24-inch-long sticks into the pile at several locations. The sticks allow them to gauge the wall thickness as they dig out from the inside.

Excavating the interior space begins by tunneling into the center of the pile at the desired entrance location. As one or two students hollow out the interior, other students remove the collecting snow from the entrance tunnel. The interior is completed when they have created a 6- to 8-foot-diameter space with 18-inch-thick walls that has enough head room to comfortably sit up or even kneel. To make sure there’s adequate ventilation in the quinzhee, they poke a small hole through the roof.

If the snow is properly compacted before excavation, the roof of the quinzhee will support being walked on the next day. But on the off chance that there is a flaw in one of the walls, Hagbrand recommends sleeping with a shovel inside the quinzhee so that you can dig yourself out in case of a collapse.

During a typical NOLS 14-day winter course, Hagbrand and her students build a cluster of quinzhees in two different locations and stay in them for four to five days.

“Making a quinzhee takes a little more effort than setting up a tent, but the extra work is worth the reward,” says Hagbrand. “It’s a super fun day of playing in the snow, and sleeping in one is an amazing experience. Quinzhees are incredibly quiet, cozy and comfortable.”

Piling snow on top of a drift is a quick way to create a snow pile deep enough to make a snow shelter, photos by Seth Lightcap

When the Snow Hits the Fan

To build a quinzhee on flat ground will take a minimum of two to three hours even with practice. In an emergency scenario, when getting out of the elements needs to happen as quickly as possible, building a quinzhee may take too much time.

In situations like this, the quickest way to build an emergency snow shelter is to find a deep snowdrift that holds the potential to dig a snow cave without having to pile up snow and wait for it to harden. Snow drifts of this size are typically found on the lee side of boulders, rock outcroppings or sometimes large trees.

After locating an ideal snowdrift, start digging the entrance tunnel to the snow cave at the lowest spot possible. The goal is to make the entrance of the cave lower than the interior space, such that your rising body heat gets trapped in the cave instead of escaping out the door. The next step is to hollow out the interior space by digging up from the end of the entrance tunnel. The priority is to get out of the elements, so the interior space doesn’t necessarily need to be that big.

If an emergency happens in an area without any snowdrifts, or the snow on the ground is very light and powdery, a quinzhee becomes the best option for an emergency shelter despite the time it takes to build one. With an hour or more to harden up, a pile of light snow will become dense enough to dig into and create a protected space.

But here’s hoping your first night sleeping in a snow structure is not the result of an emergency. Because just like those frozen fingers and toes that drove you back inside as a child, snow structures are a thrill to stay in when equipped to thrive, but not so fun when you’re just trying to survive.

Seth Lightcap is an Olympic Valley–based writer, photographer and avid explorer of Sierra rock, snow and trail. See more of his stories at www.sethlightcap.com.

No Comments