28 Nov Mountain Dreamers

The journey of the Caldwells is an epic Tahoe tale 50 years in the making

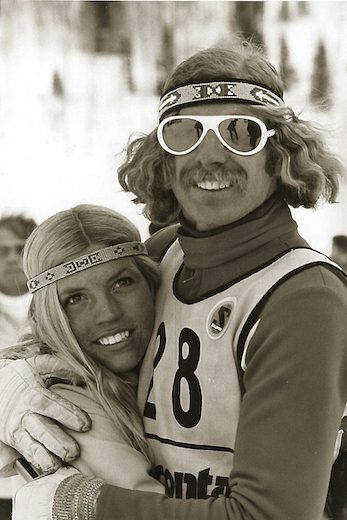

Sue and Troy Caldwell pictured at the Pecante Cup in Park City, Utah, in 1974, courtesy photo

Two teens took breaks from school two years apart, either side of 1970, and moved to the mountains. Each fell in love with skiing, then with Tahoe, then—when they met two winters later—each other.

Sue Gautschi was a ski instructor at Alpine Meadows and Troy Caldwell was a “hot dog” skier phenom. Introduced by mutual friends, they married a year later and began an improbable journey, a tale of luck, fortitude and big, pie-in-the-sky dreams. Against tall odds, they’ve accomplished much to date in an unlikely story that is still unfolding.

In the 1980s, the couple was looking for a spot to build a small bed-and-breakfast and tried to purchase 5 acres near the Alpine parking lot. Instead, the owner made them a take-it-or-leave-it deal: Buy 460 acres for the completely improbable price of $350,000, including the summit of KT-22 and about 70 acres of what is now Palisades Tahoe resort, a temple of American steep skiing.

The Caldwells sold their two houses to get cash, closed the deal and built a rudimentary road, dragging a trailer onto the property a day before it snowed 3 feet. Over the next 30 years, self-funded and often single-handed, the Caldwells built a home and shop, fabricated and installed ski lift towers for a private chairlift and, most recently, partnered with Palisades Tahoe to connect Alpine Meadows to Olympic Valley, helping create the second largest ski resort in the country.

‘An Innovator Right From the Start’

Troy Caldwell has been a force of nature since the moment he moved to Tahoe.

“I was 19 years old and got the opportunity to not go to Vietnam by getting a good draft lottery number,” Caldwell recalls. “I said, ‘OK, I’m gonna take time off school and learn how to ski.’ I was allergic to everything growing up in the Bay Area. I lived with watery eyes and a runny nose. But when I moved up here, I was allergic to nothing.”

Caldwell performs a slow dog noodle last winter at age 73, photo by Chaco Mohler

He had only skied a handful of times previously but progressed speedily from a first carved turn to skiing from the top of Alpine Meadows. Two years later Caldwell was a professional on the “Hot Dog Skiing” circuit, the world’s first freestyle ski tour and the hottest thing on snow at the time.

“He was an unknown who had signature moves right from the beginning,” remembers Wayne Wong, the enduring star of that era. “That established him as an innovator right from the start.”

Caldwell was soon invited to join Wong on the K2 Demo Team, doing contests and exhibitions on indoor ramps and moving carpets around the country.

After the Caldwells married, the couple began caretaking for the Pritzker family home (founders of the Hyatt Corporation). Sue worked at Alpine in the winter and Tahoe Donner in the summer. When Caldwell retired from the hot dog tour in 1976, he put his energy into building and selling custom homes.

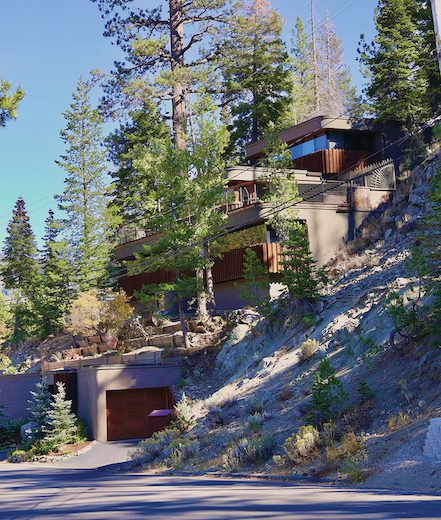

As he had on skis, Caldwell sought to innovate as a builder, in part by using more fire-resistant materials. He began welding and pouring what would become his signature home, Bunker House, in 1981: four stories of wood, concrete and dark glass built into a cliffside. Easily visible from Alpine Meadows Road, the stark structure was a modernist architectural statement.

The Bunker House built by Troy Caldwell in the 1980s, photo by Chaco Mohler

“Troy dances to a different drummer,” says Ann Hougham, who, with her former husband, Bill Beckett, built a timber “Tahoe style” home down the street around the same time. “Some neighbors weren’t fans of his architecture, but everyone loved Troy, so there wasn’t much grumbling. And it was fun to watch him work.”

With Bunker House completed, Caldwell was inspired by the newly established Stein Eriksen Lodge in Deer Valley, Utah, hoping to create something similar here.

“I still had a little notoriety at that point as a skier, and I thought it would be fun to ski with the guests,” he says. “Susie was up for it; we were going to make beds and everything to make it work.”

He identified 5 acres next to Alpine’s parking lot as a perfect location—land owned by Southern Pacific Land Company since construction of the Transcontinental Railroad in the 1860s. In spring 1989, Caldwell called Southern Pacific’s San Francisco office and made an appointment.

“We ended up in front of two giant, 14-foot-high chrome doors,” he says. “I had my best corduroy jacket on, and I thought, ‘Man, I am out of my league.’ The doors opened and a guy came out in a three-piece suit and suspenders. He took us into the office, and we started chatting.”

Serendipity in the Sierra

That chat would last six months.

After Southern Pacific discovered it could not subdivide the property, and instead had to sell the entire 460-acre holding, the company shopped the land to Palisades Tahoe behind the Caldwells’ back. But instead of speaking directly with Alex Cushing, the semi-absentee owner of the ski resort at the time, the railroad’s call went to an accountant. The resort employee declined the offer, saying buying the land didn’t make sense because their rent was so low. Cushing wouldn’t learn about the discussion until many months later, when the first rent invoice arrived from the Caldwells.

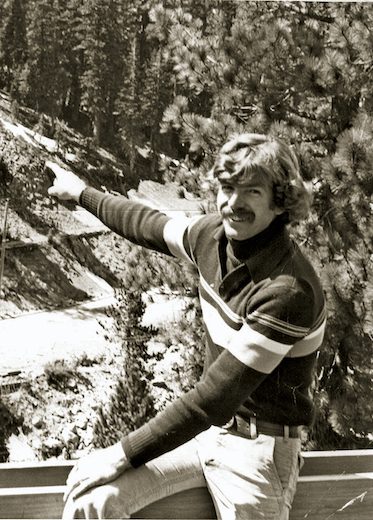

A young Troy Caldwell points to the progress of the first dirt road built on his White Wolf property, courtesy photo

The railroad determined that the quick cash served their needs. So that fall, the Caldwells were back behind the tall doors and inked the purchase for less than $800 an acre.

Their sudden windfall made them lord and lady of a small kingdom, but then they had to cash flow it. For the next six years they lived in a trailer in the snowbelt. Summers, Caldwell worked on the property and built their future home. Sue sold her car and biked 30 miles round-trip to her job in Tahoe Donner.

At night in their trailer, they’d talk about what to do with their land.

“The bed-and-breakfast was our dream,” Caldwell says. “All of a sudden we had a whole mountain. So, we started opening the dream up wider.”

The ski resorts weren’t interested in connecting. Instead, Alpine Meadows owner Nick Badami encouraged Caldwell to build lodging.

“We first envisioned a small mountain village with a ski-in-ski-out hotel and restaurants,” says Caldwell. “But people in this neighborhood (Bear Creek) thought we should keep it more residential than commercial. So, we switched to a smaller, high-end private community.”

They named the project White Wolf after a beloved pet.

With their new dream coming into focus, a stiff headwind suddenly blew down from KT-22. It was time to renegotiate the lease, and Cushing wanted to end it.

The parties spent two years hammering out a deal that would redraw Caldwell’s property lines in exchange for the ski resort transporting and installing its Headwall chairlift on White Wolf land. Caldwell says a preliminary agreement was in place before the ski area backed out. Cushing the lawyer emerged, and 14 years of litigation followed.

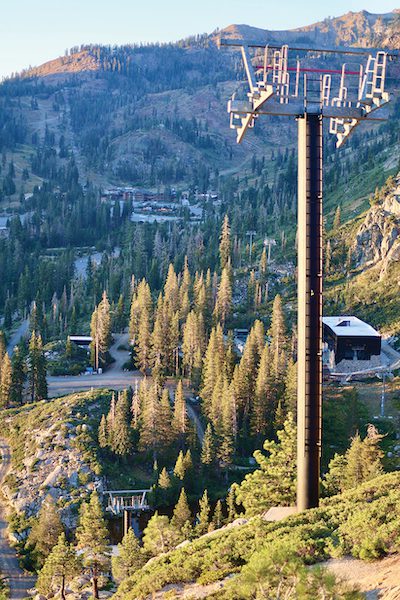

The White Wolf base area with chairlift terminal pad in foreground and Alpine Meadow base area in background, photo by Chaco Mohler

“I respected Alex,” Caldwell says. “This was an important property to his kingdom, and he was going to use all his skills. But I had my rights, so I fought hard. We weren’t sure we’d survive (the legal fees), but we prevailed.”

The deal with the resort was dead, but the vision for a private ski lift didn’t die with it.

In 1999, Caldwell secured a permit to install a chairlift up the south side of KT-22. Finding no deals on used lifts, he decided (of course) to fabricate his own. With the help of a lift expert, Caldwell welded together 17 towers in his parking lot. Contractor friends donated time and labor.

By summer 2004 the towers and their foundations were complete. That October, around 20 volunteers over multiple days helped guide the huge towers, dangling below a helicopter, onto their foundation bolts.

Come winter, the sudden presence of the shiny towers marching up the out-of-bounds slope surprised skiers. Soon many more knew Caldwell’s name, if not his story.

“That was the game changer,” he says. “Up to that point. the community saw us as just tinkering around.”

Although construction would stall, Caldwell’s lift towers—monuments to optimism—would help keep alive a 50-year-old ski industry dream of connecting Alpine Meadows to Olympic Valley.

Dreams Renewed

In 2011, the neighboring resorts finally came under one ownership, KSL Capital Partners (now Alterra Mountain Company), and connecting the two was suddenly feasible. KSL’s leaders came a-courting the Caldwells, flying them to the Alps to check out collaborative lift operation and construction examples.

“We went through a lot of negotiations as to how the connect could take place,” Caldwell says.

Sue and Troy Caldwell in front of their gondola station, photo by Chaco Mohler

He lobbied for multiple chairlifts, but the resort wanted a single gondola. Several routes were explored, including one along the Caldwells’ western property line with a station above Alpine’s Bernie’s Bowl. That route faced immediate opposition, due in part to its visibility from adjacent Granite Chief Wilderness. Instead, a gondola station was designed lower on Caldwell’s property, constructed to match his concrete, glass and stone architecture and with mechanisms to allow him and White Wolf residents to load and unload in the future.

The gondola opened in December 2022 to majority rave reviews, although some local passholders are not won over (see sidebar on page 104).

Caldwell filed for White Wolf’s subdivision permit nine years ago, to include 38 lots and a lodge with dining, bowling alley and 10 apartments, plus employee housing. In winter, there would be a hockey rink and a second chairlift heading toward Alpine, accessing a 2-mile intermediate run, as well as expert cliff lines. In summer: tennis courts and horse stables. Caldwell plans to use fireproof materials to build the lodge.

“We live in a box canyon,” he says, “and in the case of a fire emergency, we’ll be able to shelter in place the entire Bear Creek community in the lodge, over 200 people plus a number of vehicles. We’ve studied the big fires like Paradise, and we think we can create a fireproof community.”

The Caldwells have many friends cheering them on, although some remain clear-eyed about the challenges ahead.

“White Wolf has the potential to be one of the most exclusive private four-season enclaves,” says Franz Weber, the multi-time world speed skiing champion, who now runs a sports consulting company. “But having been deceived (in the past), Troy and Sue are apprehensive to trust a partner that has the expertise and needed capital to bring it to the finish line. I hope they prove me wrong and complete it on their own. I love their spirit and positive and kind attitude.”

In 2021, the environmental group Sierra Watch came out in opposition to the White Wolf subdivision. If it comes before the Placer County Board of Supervisors, there will surely be others in opposition to a wealthy enclave.

Caldwell in front of a cabin built as a prop for film shoots on his property, photo by Chaco Mohler

For now, the Caldwells find themselves busy with something they never expected for White Wolf: a niche as a closed-set location for photo and movie shoots. The couple has hosted over 200 commercial and film shoots to date, from the MacGyver TV show to Blu-ray launch ads to a recent Kevin Costner project that used the rugged property as a Yosemite-like backdrop for a series on national parks.

“It started with interest for European commercials,” says Caldwell. “But it’s grown to where 75 percent of all car manufacturers have shot commercials here.”

Caldwell does what it takes to keep everything humming, whether hiking with location scouts or operating heavy equipment. The couple, who celebrated their 50th anniversary this fall, stay fit with daily walks up the mountain, “just enjoying still having it to ourselves,” says Sue.

“Susie has been pretty cool to support me to get through all this stuff,” says Caldwell, who’s now 74. “We’ve always looked at it as enjoying the journey as much as the destination. Seeing things being built is as much fun for me as getting to the finish line.

“But it will be exciting to finish, of course. We’re hoping to see a green light on the permit soon. Susie and I are watching our time clock click and realize we better pull it off quick.”

Adds Sue with a wide smile: “Troy plans to live to 200 to get this all done—because, of course, he has to do everything himself.”

Chaco Mohler is the former publisher of Tahoe Quarterly and the magazine’s first editor-in-chief.

Hot Dogging Heyday

The most fun ski craze to ever hit America was hot dog skiing in the 1970s, when posters of Wayne Wong leaned back in a wong-banger and Susie Chaffee getting air in skin-tight white pants adorned college dorm walls coast to coast.

“It was something new and creative that the kids were excited about, so it got lots of immediate attention,” says Caldwell, who joined the tour in 1972 at age 21.

Wayne Wong in classic form, courtesy photo by Chris Speedy

Midas Muffler and Chevrolet were the initial title sponsors of the inaugural hot dog skiing tour, and the big daddy of sports TV at the time, ABC Wide World of Sports, broadcast the contests.

Heavenly on Lake Tahoe’s South Shore hosted one of the first hot dog skiing competitions in 1971 and became a regular stop on the national tour. The resort was a bona fide mecca of freestyle skiing, owning to its steep Gunbarrel mogul run and its aerial heritage, dating to Olympic champion Stein Ericksen’s daily flips off the top of Gunbarrel in the 1950s. In the hot dog era, Heavenly ski patrolman Chris Thorne burst on the scene and became world mogul champion.

Heavenly was also a fortuitous launch pad for the unknown Caldwell, who had only two years of skiing under his 28-inch belt when he entered.

“I had learned how to do some tricks and entered the competition at Heavenly Valley and took 11th place,” he says. “That was enough to get me invited to National Finals in Sun Valley.”

In those early contests, competitors did all three disciplines on one continuous run, starting with moguls, then a big jump mid-run and ending with ballet moves. Therefore, Caldwell the ballet specialist couldn’t be a one-trick pony.

Caldwell’s competitive highlights included a second-place finish in ballet at the 1974 World Championships, just one point behind John Clendenin, a South Lake Tahoe resident at the time. During those years, Clendenin and another world champion skier, “Wild Bill” O’Leary, ran a summer training center in Meyers, eventually moving it to Zephyr Cove, where they built a huge jump into Lake Tahoe.

Wong, a longtime Reno resident, is one of the era’s most enduring stars. But he says of Caldwell, “Troy is definitely one of the people who put freestyle skiing on the map. He’s one of the true gentlemen of our sport.”

Merging Snow Tribes

People like being part of a tribe, a “community” in modern parlance. This includes season passholders who form loose groups around individual ski areas, or even specific chairlifts. They might spend 80 or more days a winter at one resort and are deeply connected to the mountain, if sometimes less so than the company that operates it.

Recently, citizen snow tribes loyal to Homewood and Palisades Tahoe have spoken out against each ski area’s plans. Connecting Olympic Valley to Alpine Meadows was a decades-long ski industry dream, first promoted by Alpine founder John Reily, but it wasn’t a dream shared by everyone.

One person with mixed feelings, ironically, was the owner of the land between the two ski areas. Caldwell had learned to ski at Alpine and his wife worked there for decades. Of the resort formerly known by the initials SV, Caldwell says, “They had their way of dealing with the world and we had ours, and everybody was kinda happy with the way things were.”

The two resorts developed different cultures in part because of differences in terrain—SV the hard-charging home of ski champions and super experts, Alpine with a more relaxed backcountry vibe, created in part by its open-boundary policy.

When the Caldwells found themselves owners of the land in between, some lobbied them to help link the resorts. Ski movie legend Warren Miller paid the couple a visit, telling Caldwell, “‘We need to connect these two mountains.’ And Warren was a pretty good salesman,” Caldwell says.

When KSL Capital Partners, now Alterra Mountain Company, took ownership of the resorts in 2011, talks soon began with the Caldwells about connecting the two. Both snow tribes caught wind of it.

“We heard rumors that there was great concern,” Caldwell says. “Nobody came up to us and said, ‘This stinks.’ But it was apparently the talk at dinner parties.

“I understand. This was changing our mountains, the way we grew up and what we knew. But I found (KSL’s) attitude was, ‘How can we make the skiing experience more friendly for everyone?”

With the gondola starting its third season of operation, many on both sides are pleasantly surprised.

“I’m a fan of the new gondola,” says two-time Olympic gold medalist Jonny Moseley. “None of the changes have rubbed me the wrong way. And I haven’t noticed it overcrowding any runs on KT.”

The Caldwells have heard from previous skeptics who now praise the gondola and the freedom to roam through four valleys of ski terrain between the Sherwood Express and Granite Chief chairlifts. Others enjoy just taking the gondola from Alpine to Olympic Valley for lunch.

Yet, holdouts exist. Among the most passionate and imaginative of these are the Alpine Meadows skiers who sport a variety of “Alpine Rebel Alliance” stickers on their skis and cars, referencing the out-gunned heroes of the Star Wars movies.

Caldwell is philosophical: “We think the gondola’s done great things for the larger community. But we know there are die-hards who don’t feel that way.”

“On the other hand,” says Sue Caldwell, “we know of some locals who said they’d never ride the gondola. But then we’ll be out for a walk and we see their faces in the gondola cabin windows as it passes by.”

No Comments