25 Jun Reinventing the Wheel

How a group of counterculture cyclists channeled the frenetic times of the 1970s to build the bikes that would open miles of terrain and unleash a brand-new sport that’s still on the rise

It wasn’t altruism that drove Max Jones to clear brush from the antiquated trail that once served as a flume from Lake Tahoe to Virginia City.

“It was purely selfish,” Jones says. “It was all just so I had a ride to do.”

In 1983, Jones, who was testing out his new off-road bike on the Tunnel Creek Trail near Incline Village, began the laborious process of clearing fallen trees and other debris from the scenic ridgeline route.

“There was about 3 miles of aluminum pipe that had to be reclaimed and recycled,” Jones recalls. “I’d say anywhere from 50 to 70 trees had fallen across the trail, so those had to be cut away.”

Landslide debris had also covered portions of the path, while the old flume bed had fallen away in places and needed to be re-established. But after months of work, Jones rebuilt what is considered one of the most spectacular mountain bike trails on earth. The Flume Trail Ride stretches about 13 miles from Spooner Summit to the outskirts of Incline Village, traversing the steep hillside some 1,500 feet above Tahoe’s East Shore.

“It’s one of the most beautiful in the world,” Jones says. “I’ve ridden some pretty nice trails, but nothing beats this.”

But while Jones was one of the pioneers of mountain biking at Lake Tahoe, the practice of riding bikes off-road was prevalent long before he cleared the first branch from the Incline flume.

Members of the 25th Infantry Regiment of the U.S. Army, known as the buffalo soldiers, pose with their off-road bikes on Mineral Terrace in Yellowstone National Park in 1896, photo by Haynes, F. Jay, courtesy Montana Historical Society Research Center Photograph Archives

The Forebears of Mountain Biking

In the 1890s, Lieutenant James A. Moss of the U.S. Army’s 25th Infantry Regiment was eager to prove to his superiors that bicycles offered a superior mode of transportation in mountainous terrain. He believed cycling was swifter than marching and cheaper than feeding horses.

The 25th Infantry was comprised of the famed buffalo soldiers, one of four regiments made up entirely of African American men after the Civil War. The infantry and cavalry regiments served mostly on the Western frontier during the Indian Wars.

Members of the 25th Infantry Regiment in formation, with Lieutenant James A. Moss riding alongside the two rows of soldiers, photo courtesy University of Montana, Missoula, Mansfield Library

The soldiers’ bikes were single-speed rigs that weighed approximately 60 pounds when fully loaded with gear. Despite these impediments, the regiment biked 1,900 miles from Missoula, Montana, to St. Louis, Missouri, navigating unpaved paths in just 40 days. They averaged over 50 miles a day, which may sound unimpressive to seasoned bikers used to 100-mile days, but considering the technology and quality of roads, covering such a distance was quite a feat.

In addition to not requiring food or water, the bikes were also relatively quiet, making sneak attacks more viable than on horseback.

While Moss proved his hypothesis, the advent of the internal combustion engine rendered the experiment largely irrelevant to an army looking to modernize its forces.

Off-road bicycles also played a role in the Klondike Gold Rush in the 1890s. Miners hoping to hit paydirt in the harsh northern wilds were forced to navigate a series of snowbound mountain passes or wind their way up frozen rivers, and many chose to ride bicycles through the rugged terrain in search of gold.

The theory was that bikes could follow the tracks made by dogsleds, were faster than dogs or horses, and didn’t require food or water. However, the men who biked on frozen rivers in temperatures well below freezing left accounts that did not attest to any degree of comfort.

“I believe it was 23 of February and the thermometer down to 48 below zero,” wrote renowned gold-seeker Edward Jesson. “The rubber tires on my wheel were frozen hard and stiff as a gas pipe. The oil in the bearings was frozen and I could scarcely ride it. My nose was freezing and I had to hold the handlebars with both hands, not being able to ride yet with one hand and rub my nose with the other.”

Jesson famously rode more than 1,000 miles from Dawson City to Nome during the Klondike Gold Rush, covering much of the route on frozen rivers.

Mountain biking pioneer Joe Breeze competes in the Repack race on Mount Tamalpais on his custom-built Breezer #1, circa 1977, photo by Larry Cragg, copyright Rolling Dinosaur Archive

“They were hauling themselves on Klondike Bikes to get to the frozen Yukon,” says Joe Breeze.

Breeze, curator at the Mountain Bike Hall of Fame in Marin County, is widely credited with building the first purpose-built mountain bike in 1978. He grew up in Mill Valley and inherited a love for cycling from his father, an automotive machinist who cycle-commuted to work in Sausalito in the 1950s, and kept in shape for sportscar racing by riding his European lightweight bicycle. But Breeze, a legendary cyclist and pioneer of the sport, is also a historian.

He notes that cars have their roots in bicycles. The Dodge brothers, for example, founders of the Dodge brand of American automobiles, started as bicycle manufacturers in the late 1890s before making their own line of cars in 1914. “Chevrolet was a bicycle frame builder in France before coming to America to build cars,” he adds.

Breeze says the popularization of the balloon tire by the Schwinn bicycle company in the 1930s paved the way for off-road mountain bikes of the future.

“You had kids riding those Schwinns out to their local fishing holes or bombing down the Ozarks in the 1930s and 1940s,” Breeze says, pointing out that off-road biking was certainly happening before the 1970s.

Nevertheless, it was Breeze and his fellow cyclists who transformed off-road bicycle riding from the intermittent form of transportation of a few assorted enthusiasts to a full-fledged sport and dominant outdoor industry.

“You can’t downplay the impact that riding in Marin County in the late 1970s had,” says Breeze. “It was the crucible of mountain biking.”

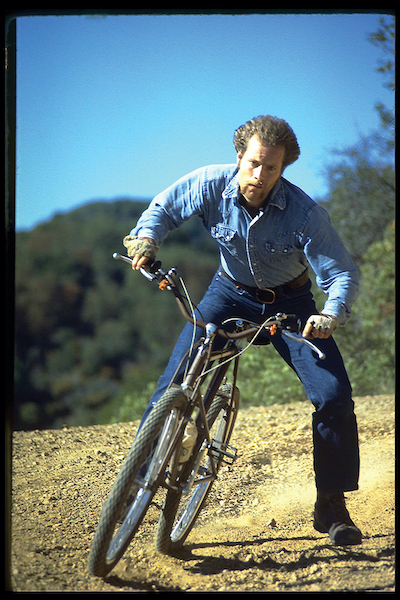

Joe Breeze of the Larkspur Canyon Gang tears around a corner aboard Otis Guy’s state-of-the-art, fully modified 1942 Schwinn Excelsior, photo by Larry Cragg, copyright Rolling Dinosaur Archive

Mount Tamalpais and the Larkspur Canyon Gang

While off-road cycling existed as early as the nineteenth century, the cradle of mountain biking, as it is now known, is Mount Tamalpais, the often fog-shrouded mountain in Marin County that looms over the San Francisco Bay Area.

In the early 1970s, a motley rabble of teenagers from Larkspur took Schwinn newsboy bikes from the 1940s and stripped them down, fitted them with thick, knobby bicycle tires and began riding down the fire roads of “Mount Tam.”

This group is known as the Larkspur Canyon Gang, and most were more about thrill-seeking and partying than they were pure cyclists. Marin County was sometimes called Haight-Ashbury North, and the counterculture acolytes were just as profuse in the scenic communities that dot the area as they were in San Francisco.

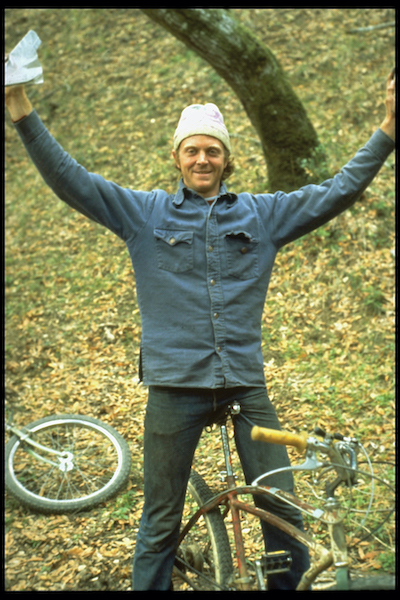

Gary Fisher celebrates a Repack victory in 1977 on his 1941 Schwinn, photo by Wende or Larry Cragg, copyright Rolling Dinosaur Archive

In 1972, Breeze, Gary Fisher, Charlie Kelly, Alan Bonds, Otis Guy and a host of others formed the Velo Club Tamalpais. Initially, the club focused on road racing on skinny-tire bikes with drop handlebars—and had nothing to do with off-road biking.

Breeze, Fisher and the others were put off by the straitlaced aspect of most of the established road-racing clubs, however, so they formed something less square in the Velo Club Tamalpais.

“We were hanging out with Ken Kesey and the Merry Pranksters and the Grateful Dead,” says Fisher (although Breeze says he personally had no association with Kesey and did not partake in drugs). “Charlie Kelly was a roadie for the Sons of Champlin.”

But they were also serious cyclists.

Breeze and Fisher, in particular, ranked among the top 15 in the country at various points in the 1970s and both harbored dreams of competing in the 1980 Summer Olympics in Moscow (which the United States ended up boycotting).

So, while they were still committed to winning races, they didn’t feel the need to follow any brassbound regime to do so.

“It was the ’70s and I met Marc Vendetti, who had just graduated from Redwood High School in Larkspur, and he was riding with these guys called the Larkspur Canyon Gang,” says Breeze. “We both found that we had an interest in the sophisticated machines of bicycling’s 1890s Golden Age. We were soon on the lookout for such bikes, hoping to share cycling’s vast history with others.”

But things soon got derailed. On a bike-finding foray, Breeze and Vendetti struck out on Golden Age bikes, and Vendetti suggested Breeze buy a 1941 balloon-tire bike they saw. When Breeze replied, “What am I going to do with that sled?” Vendetti suggested he might ride it down Tamalpais.

“I hitchhiked up Panoramic Highway and rode down the old Tamalpais scenic railway grade. By the time I reached the bottom I was hooked,” says Breeze.

Joe Breeze’s customized 1937 Schwinn Excelsior, circa 1977, photo by Wende Cragg, copyright Rolling Dinosaur Archive

Breeze rode his Schwinn ballooner to a Velo Club Tamalpais meeting, and others soon followed suit.

At the time, balloon-tire bikes manufactured by Schwinn, Colson and Shelby in the 1940s were still to be found in some Bay Area bicycling shops and junkyards. The boys initially used the newfangled bikes, which they called “klunkers” or “ballooners,” for fun in the offseason to their serious road-racing pursuits, but soon their competitive nature migrated to their recreational endeavors as well.

“We were a bunch of competitive guys,” says Breeze, “and we had to prove who was fastest.”

They’d strip the superfluous parts off the bikes while retaining the 1-inch-pitch drive trains. Using trial and error while careening down the pathways of Mount Tam, they discovered the utility of 1940s Morrow coaster brakes and Schwinn cantilever front brakes that allowed cyclists more power and reliability with their braking systems. As competition heated up, they’d use performance parts of the day from road bikes and motorcycles.

The first recorded mountain bike race was held on Mount Tamalpais in 1976 and was called Repack. They called it that because racers had to repack their coaster-brake hubs with grease after much of it burned off as the bikes tore down 1,300 vertical feet in about 2 miles.

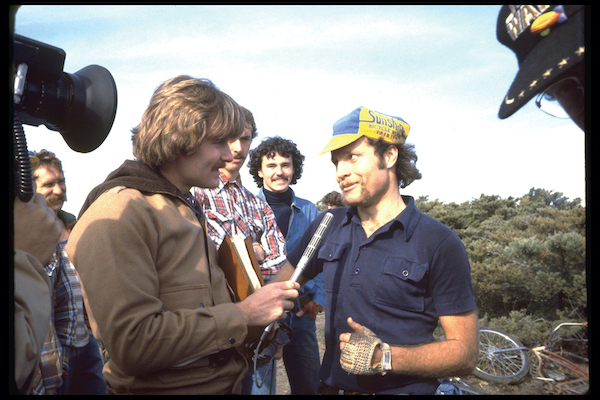

Steve Fox from San Francisco’s KPIX Evening Magazine interviews Joe Breeze about Repack and the new sport in 1979 as Les Degan, Otis Guy and Tom Ritchey look on, photo by Wende Cragg, copyright Rolling Dinosaur Archive

“By the time racers reached the bottom, they’d be followed by a contrail of smoke as all the grease vaporized,” Breeze says.

The first race was a mass-start event, but Fisher and Charlie Kelly soon instituted the use of chronometers in a time-trial format, starting riders at two-minute intervals. That way they wouldn’t be bumping their best friend off a cliff.

While Alan Bonds won the first race, Fisher and Breeze went on to have the most overall success.

“I beat Joe in every single race that mattered,” Fisher says.

But Breeze points out that he won the most Repack races, with 10 victories. Also, when Breeze and Fisher raced head-to-head, they were essentially even, each winning three races and always finishing within one second of one another. Over the 24 Repack races from 1976 to 1984, Fisher recorded the fastest time at a scorching 4 minutes and 22 seconds.

“I didn’t want to crash, but I got used to losing traction,” Fisher says.

The Repack races, which were typically punctuated with keg parties, drew increased attention to the sport.

Wende Cragg rides her 1978 Breezer on granite rocks above Loon Lake near Desolation Wilderness. She and her then-husband took many of mountain biking’s early photos, photo by Larry Cragg, copyright Rolling Dinosaur Archive

The Female Pioneer

Many of the greatest mountain bikers of all time have been women. But one woman, Wende Cragg, is often overlooked in terms of the contributions she made to the advent of mountain biking in Marin County in the 1970s.

“I was totally oblivious I was making any type of contributions,” she says. “There was a whole bunch of guys and I think they wanted a feminine touch to kind of lighten things up. They were a bunch of really competitive guys, but they were also really gentlemanly to me. They mentored me, coached me and encouraged me at every step.”

Cragg proved right at the outset of the sport that she had no problem hanging with the hard-charging boys. She participated in some of the Repack races and posted respectable times, including finishing just one minute shy of Fisher’s record time. Yet, Cragg wasn’t a professional cyclist by any means. She was interested in the sport almost solely for the spirit of adventure.

“I was named after Wendy Darling in Peter Pan and I always had the sense of wanting to fly,” Cragg says. “Well, getting on a bike captures that sense of flying.”

Cycling came in a pivotal moment in Cragg’s life, as she was struggling through a divorce, wrangling with the death of her brother and dealing with other personal issues.

“I once cycled 76 days in a row,” she says. “I’d go out by myself for a day of exploring.”

There were no trail restrictions in the 1970s, and hiking wasn’t as popular, meaning Cragg and her compatriots had the run of the place. And they enjoyed it to the fullest, sometimes solo but sometimes in formation.

“A lot of times, as a group, we would just spend the entire day outside,” she says. “We’d bring a lunch, a frisbee and plenty of weed.”

Joe Breeze poses with Breezer #1 at the bottom of Repack in 1977 after winning the race on the bike’s maiden voyage. The bike, which weighed 38 pounds, was the first purpose-built, chrome-moly mountain bike frame built up with all-new components, photo by Larry or Wende Cragg, copyright Rolling Dinosaur Archive

Building a Better Mountain Bike

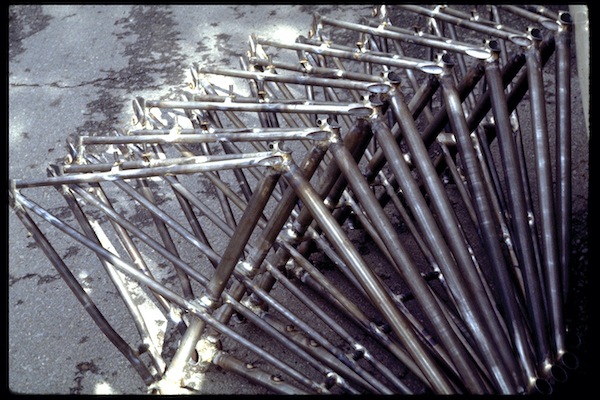

Breeze came to realize that, while the Schwinn bicycles from the 1940s were certainly better than road bikes for bombing down a mountainside, they were not ideal. So in 1977, at Kelly’s insistence, he took a crack at building his own, becoming the first person to build an all-new, purpose-built mountain bike. Breeze, who was a bicycle frame builder, used straight chromium/molybdenum steel aircraft air-frame tubing, making the frames lighter and stronger—and thus better able to withstand the bone-rattling descents on Mount Tam. They were klunkers no more.

His first Repack race on his newly constructed bike, appropriately named the “Breezer,” ended in victory.

Breezer frames with their conspicuous ‘twin laterals’ ready to be nickel-plated, photo by Wende Cragg, copyright Rolling Dinosaur Archive

“Right then and there, I was able to sell all the unspoken-for frames out of the first 10 I built,” Breeze says. “You could win on this thing.”

Fisher was not among his early customers, opting instead to build his own. He approached Tom Ritchey, widely regarded as one of the preeminent bike frame builders in the world, to build a streamlined mountain bike to rival the Breezer.

Ritchey came up with the clean and elegant design that provided the foundation for the modern mountain bike. Fisher then used that design to found a company with Charlie Kelly called MountainBikes in 1979.

“I was the one who invented the term ‘mountain bike,’” Fisher says, adding that he wanted to “go big” after realizing the market potential for these bikes.

Mike Sinyard, the founder and CEO of Specialized Bicycles, confirms in the 2006 documentary Klunkerz that the design for the first mass-produced mountain bike, called the “Stumpjumper,” was influenced by Ritchey. By the mid-1980s, every major bicycle manufacturer, many of which scoffed at the notion of a mountain bike previously, had at least one line of the off-road bicycles for sale.

The outdoor recreational activity, which grew to a $7.3 billion industry by 2018 and has taken off meteorically since the coronavirus pandemic, was created by a bunch of Northern California nonconformist hippies just looking to have a good time.

“I can remember being out on a trail with Otis Guy and we stopped at a point that looked out over the Bay Area and I said, ‘Boy, this sure is a whole lot of fun, but who else is going to want to do this?’” Breeze recalls.

The answer, apparently, is nearly everyone.

Longtime South Lake Tahoe resident Gary Bell, one of mountain biking’s pioneers and owner of Sierra Ski & Cycle Works, stands in his shop with a ‘klunker’ that he built in 1978. He sold similar custom builds around that time for $600, photo by Brian Walker

Tahoe Influence

As Fisher points out, “Tahoe is like an annex of Marin County.”

He remembers road racing in the area and considers Tahoe one of the most scenic places to ride a bike of any kind.

Breeze, whose family owned a place at Marla Bay on Tahoe southeast shore, agrees.

“I first rode a bike from Mill Valley to Tahoe when I was 14 and did so many times over the years, eventually doing the ride in one day,” Breeze says, adding that, by the 1980s, he was riding the Flume Trail and racing the Tahoe-Roubaix and TNT Classic out of Tahoe City.

But the development of mountain biking in Tahoe owes credit to Max Jones, who built the Flume Trail, and Gary Bell, who not only helped develop the epic descent called Mr. Toad’s Wild Ride, but also helped found the Tahoe Area Mountain Biking Association (TAMBA) in 1988.

Gary Bell’s 1988 Mountain Goat Whisky Town Racer built by Jeff Lindsay in Chico hangs on a stand in Bell’s South Lake Tahoe shop, photo by Brian Walker

“I was a road biker, but riding the roads made me scared of cars, and I got tired of trying to ride road bikes in the dirt,” says Bell, who opened Sierra Ski & Cycle Works in 1980 and still runs the shop to this day.

Bell says he was familiar with the development of mountain biking in Marin County.

“There’s a picture in the Marin Mountain Bike Museum of 20 of us lined up before a Repack race,” Bell says. “It was Gary Fisher, Charlie Kelly and Wende Cragg. I was in that picture too.”

Like his counterparts in Marin County, Bell took an old steel-frame bicycle and started making modifications, including gears so that he could ride the bike up the mountain as well as down.

But he needed a trail.

“Myself and a couple of friends built Mr. Toad’s Wild Ride,” Bell says. “There was an existing stock trail and a hiking trail and we just made a connection in between.”

The result is a technical singletrack ride for 5.2 miles of wildness beginning at the Tahoe Rim Trail and flowing down to the town of Myers.

“Every time I get to the bottom I think, ‘Mr. Toad never fails,’” Bell says.

The top section, in particular, is for advanced riders only, but the trail does afford ample opportunities for long loops that give riders an extended experience of the terrain in and around South Lake Tahoe.

“They come from all over to ride that trail,” Bell says.

The difference today is that most of the riders are on full-suspension mountain bikes, which make it far easier to devour the rugged terrain at a swift clip. Bell and his compatriots didn’t have the luxury of suspension, while their braking mechanisms, unlike the hydraulic and disc versions available today, were suspect at best.

“It was pretty eye-rattling,” Bell says. “But it taught me to pick the right line through rougher terrain. These days you just point it and let the bike do the work.”

Bell doesn’t mean that in a get-off-my-lawn type of way. He is pretty philosophical about most controversies relating to mountain bikes—i.e., whether e-bikes should be prohibited from certain trails or whether bikes should be allowed in wilderness areas.

“It’s OK to have some places that bikes can’t go,” he says.

But Bell became a steady advocate for mountain bikers in the late 1980s, as conflicts between bikers, horse riders, hikers and other recreational users began to pick up.

“I think as riders started riding more of the hiking trails in the area, hikers started to demand no more mountain bikes,” Bell says.

Tahoe’s Upper Tyrolian Trail under construction, photo courtesy TAMBA

Recognizing a potential threat, TAMBA began working with the Forest Service and other land managers to designate certain trails for mountain bikers while agreeing to concede other trails in the Tahoe Basin.

“When we saw those conflicts in Marin, we wanted to get ahead of it and prevent things from getting really ugly here,” Bell says.

Ben Fish, the current president of TAMBA, says he and others resurrected the advocacy organization in 2011 after some trails were being rerouted to the dismay of area mountain bikers.

“There were legitimate fears of losing access to trails,” Fish says.

But things have evolved since then. Many Forest Service employees were avid mountain bikers themselves, so access was retained, and the focus of the organization shifted to increasing the number of trails in the Basin while cutting down on illegal trail-building.

“We’re really growing right now,” Fish says. “We have a three-person trail crew, a trail director and a full-time staff person.”

The organization helped develop the Corral Trail on the South Shore, among others, and is putting the finishing touches on the Upper Tyrolian Trail in Incline Village.

The recent projects cement Tahoe’s increasing status as a destination for mountain bikers.

“We have so many trails that are so totally world-class,” Bell says.

Jones, builder of the Flume Trail in the 1980s, echoes Bell’s sentiment.

The view of Sand Harbor from the Flume Trail, photo by Sylas Wright

“That trail is such a big draw,” Jones says of the Flume. “It gets people in the park.”

The Flume Trail, which traverses a spectacular lake-facing ridgeline above Sand Harbor, attracts about 70,000 riders per summer. While the trail is not as technically difficult as Mr. Toad’s and others in the Tahoe area, it is unquestionably the most scenic.

Jones, a Mountain Bike Hall of Fame inductee who raced professionally until 1996, organized several races on the Flume Trail beginning in 1984, garnering even more attention for the sport.

Today, Jones runs Flume Trail Bikes while his wife Patti McMullan runs the adjacent Tunnel Creek Cafe, providing shuttles to mountain bikers looking to start at Spooner Summit and ride one way back to Incline Village.

“I really just stumbled across it,” Jones says of the trail that has loomed over his personal and professional life. “I had just started mountain biking up and down Tunnel Creek and I wanted to find a loop.”

Jones, Bell, Breeze, Fisher and the rest of mountain biking’s pioneers all attest to the importance of Northern California to the sport’s advent. While some went on to launch successful companies, all agree that the biggest contribution was increasing the amount of fun people could have in the outdoors.

“I believe in the bike’s ability to bring a lot of happiness,” Fisher says. “Let’s just cover the earth with bikes.”

Santa Cruz-based writer Matthew Renda is a former Tahoe resident and an unexceptional mountain biker who thoroughly enjoys the sport nonetheless.

Charlie Kelly (@Repack_Rider)

Posted at 06:18h, 12 JulyFor a second hand account, this is very well researched. One minor point. Alan Bonds was not a founding member of Velo Club Tamalpais, and was never in fact a road racer or a member of the club.

Anyone who would like a much longer first hand account of these events can check out my book, “Fat Tire Flyer: Repack and the Birth of Mountain Biking.”

Billy Savage

Posted at 22:11h, 14 SeptemberOr you could watch the film, Klunkerz, mentioned and quoted in the article. 😉