30 Nov Robb Gaffney: ‘The Wild Ride is Normal’

Tahoe ski icon, author, community pillar and psychiatrist Robb Gaffney reflects on his new book project, life after extreme sports, the power of community and fighting cancer

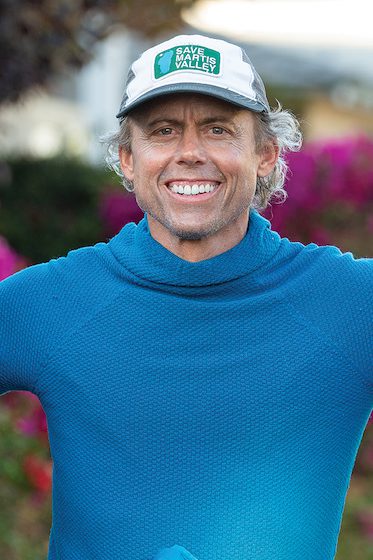

Robb Gaffney in June 2022, the day after learning his cancer was still present, meaning he will need lifelong monthly infusions, photo by Steve Gaffney

Robb Gaffney is outdoors.

As you read this, there is no way he is sitting inside.

If you know Robb personally, you most likely encountered him in an outdoor setting. You may have crossed poles with him on the side of a mountain, or perhaps you walked along a wooded path with him as you discussed life. Maybe you first saw him toying with gravity onscreen in one of half a dozen ski movies that capture his fluid (and some would argue underrated) grace. In flicks like 1999—made by Robb’s brother, Scott—he glides over hillocks and humps like hot oil poured onto the slope, kicking up massive clouds of steam.

If you don’t know Robb personally, you’ve surely at least seen footage of his skiing prowess, or a talk he gave as part of his movement to increase the lifespans of extreme athletes, or an interview in opposition to big development plans for Olympic Valley.

OK, sure, there’s a chance he’s indoors.

He may be seeing a patient at his psychiatric practice or getting one of the monthly lymphocyte infusions he will likely need for the rest of his life to keep his acute myeloid leukemia in check. Or he may be editing a passage in his book about life with cancer that he hopes to publish in late 2023.

“When I first was diagnosed with cancer [in 2019], I didn’t know how to share the news,” he says.

Should he put out updates on social media? Keep it more intimate?

He settled on letting people know the basics of what was happening via caringbridge.org. Soon, however, he began moving beyond the basics to pen more emotional posts. He began to test himself to see how transparent he could go, and people responded positively. Ultimately, he got some specific feedback from friends and family following his journey: Write a book.

“At that time, the last thing I wanted to do was write a book,” he says, noting that he was often reeling from cocktails of toxic chemicals intended to fight the cancer or high doses of steroids. “I was miserable.”

Even when he did feel motivated, he labored to simply get out a paragraph or two. But as his treatment progressed, he began to feel something of an obligation to share what he’d been learning. So he wrote when his mind felt clear enough. Sometimes the results were good. Sometimes he looked back and wondered what he was thinking at the time: “It didn’t make sense!” To be fair, he occasionally pounded out words while under the influence of 120 milligrams of prednisone.

When it comes to wrestling his thoughts into a readable form, Robb does have experience on his side. In 2003, he self-published Squallywood, which details Palisades Tahoe’s steepest and gnarliest lines and features a bonkers guest-written chapter by the late Shane McConkey, who laid out the rules for an ongoing game that dishes out points for outlandish and frequently self-deprecating stunts. (If you haven’t read the book, good luck, as used copies currently sell for $575 to $1,002 on Amazon.)

So yes, Robb, now 52, does spend time indoors—to write, to edit, to work, to fight.

But if you really wanted to play the odds, you’d put your dollars on there being nothing over his head but bright blue sky and maybe a few snow-frosted Jeffrey pine boughs.

Robb still skis, but instead of freefalling from cliffs in view of cheering spectators on chairlifts, he can now most likely be found in the Tahoe backcountry or Eastern Sierra. Backcountry skiing is an activity he estimates makes up about 70 percent of his recreational activity these days. He hasn’t skied a resort in about four years. He also frequently hikes with his children—Noah, 22, and Kate, 20—but he heads out with friends, too. Or he could hop into a kayak or a raft bound for whitewater. And he just took up climbing this past summer.

In every way that matters, Robb Gaffney is outdoors: to wander, to heal, to grow, to live.

Robb Gaffney takes advantage of prime early-season conditions in the Mount Rose backcountry in November 2014, photo by Matt Bansak

Finding Tahoe

As a psychiatrist, Robb is no stranger to the concept of “nature vs. nurture”—as in whether your genetics or upbringing shape your behavior and persona. His devotion to the outdoors is obviously the product of both.

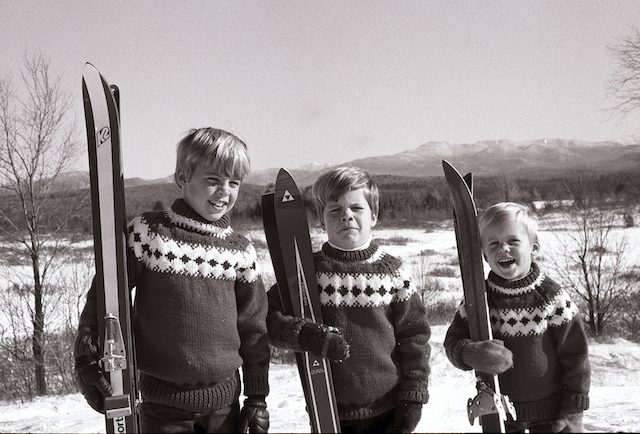

“Robb was always the best young skier on the mountain. He could do anything on skis,” says Scott Gaffney, longtime director of ski film company Matchstick Productions and Robb’s older brother—though he admits that the discrepancy in their maturity levels leads people to assume Robb is the elder.

The three Gaffney brothers, from left, Steve, Scott and Robb at Tupper Lake in the Adirondack Mountains of New York in 1976, photo by Jim Gaffney

Unfortunately, being the best doesn’t mean being impervious to injury. Scott remembers Robb banging his face into his pole after he landed a jump at Big Tupper, their home mountain where they grew up in the Adirondacks.

“He was probably 8 years old,” Scott says. “The pole broke his two front teeth off. The nerves were dangling out. He was dying skiing down [because] the cold air he was breathing in was getting the nerves.”

The Gaffneys didn’t let such injuries slow them down, and they didn’t always stick close to home, sometimes driving thousands of miles to camp on the opposite side of the country for a summer. Tahoe was a repeat destination, likely due to a combination of factors, including the facts that, well, it’s Tahoe, and that the locale played a role in Robb’s parents’ early relationship.

Robb and Scott first experienced a Tahoe winter in 1991, when Scott was shooting his first ski movie, Adrenaline Descents, and working as a lift op at Keystone, Colorado, while Robb attended the University of Colorado Boulder. After Robb graduated, the brothers moved to Tahoe for the 1993-94 season, working in race services at what is now Palisades Tahoe.

“Neither of us were too enthralled with the Colorado snowpack,” Scott says, adding that they knew Tahoe was the epicenter for winter sports—thanks in part to seeing the Warren Miller movie Ski Time in their early teens. Made during the big winter of 1983, the movie features a young Scot Schmidt in his breakout role “and all these people we started revering.”

Robb returned to Colorado for med school in 1995 before moving back to Tahoe—where Scott stayed all along—four years later. Together, they made at least half a dozen ski movies, gathering much of the footage at Olympic Valley’s storied ski resort, which Scott describes as an “arena where we knew great things happened.” Many of the flicks included their good friend McConkey, whom they convinced to follow them from Colorado.

“I was almost more of a ding and dong with Shane McConkey than I was with my brother,” Scott says, noting that he can’t quite remember exactly how many films they made. He can, however, remember the attention Robb’s skiing drew.

Robb Gaffney, left, with brother Scott during the filming of 1999, photo by Hank de Vré

“A lot of people over the years have remarked on his style,” Scott says. “Connery Lundin always remarks on Robb’s ‘quiet hands.’ He has these really calm hands in his skiing, meaning his arms aren’t all over the place. It’s just a little move of the wrist.”

While skiing style is no small thing, Scott says that, on a deeper level, “people respect him for pretty much everything he does. It’s kind of crazy the positive impacts he’s had on people on so many different levels.”

Now, Scott and his family live four houses down from Robb and his family in Tahoe City—and their ongoing proximity sometimes causes confusion in the community.

“I get called Robb all the time, and I don’t think he ever gets called Scott. I don’t know what that’s all about,” Scott says with a laugh.

Still, the two have carved out their own identities. Robb traded his crazier skiing days for a career in medicine, graduating from his residency at UC Davis in 2003 before permanently moving to Tahoe’s North Shore. Scott has continued to make iconic ski films, including 2011’s G.N.A.R., based on the stunt-fueled chapter in Squallywood. Robb did join that production, leaning into his evolved role as elder statesman in the skiing community by cheekily donning magisterial garb, including a curled wig piled as high and white as a Tahoe powder day.

That movie served not just as an ode to “debauchery”—as Robb describes it—but also as an homage to McConkey, one of the most famous athletes to ever write his name on the blank white canvas of Olympic Valley. Likely in yellow.

McConkey was a beloved fixture on the slopes—even if his occasional nude runs irked resort officials as much as his freeskiing awed his fans around the world—until his death in March 2009 in an extreme sports accident that was tragically not an isolated incident among Tahoe athletes.

C.R. Johnson and Arne Backstrom both died while skiing in 2010. Kip Garre and Allison Kreutzen died in an avalanche in 2011. Timy Dutton died in a skydiving accident in 2014. Dave Rosenbarger was killed in an avalanche in 2015, and ski BASE jumper Erik Roner died the same year after crashing into a tree while skydiving.

Numbers in Safety

Prompted by the death of so many friends in the sporting world, Robb launched Sportgevity, a campaign devoted to improving athletes’ longevity in sports.

“In the 2000s, we lost a lot of friends,” Robb says. “Risk was going up exponentially at the time. I was raising two kids in an environment losing some of our biggest heroes. The last thing I wanted was to lose children to sports I love.”

In addition to local projects, lectures and educational seminars, Robb appeared on an NBC Rock Center with Brian Williams segment.

Renee Koijane, an oil painter whose shop, Muse, happens to be in front of the Gaffneys’ home, was with Robb at the golf tournament in Olympic Valley where Roner died while skydiving in as an opening stunt. She explains that Roner’s death was the nail in the coffin for her, “quite literally.”

“I’d never talked to Robb except casually in passing,” she says. “I called him the next day—not for psychiatric help, but for someone to process, and I saw with his Sportgevity [that] tangentially he might relate.”

The two put together some seminars for the North Tahoe community. One was called “Why the Huck?” focusing on psychological factors that could propel people to put themselves in precarious, life-threatening situations.

“Then he and I did TEDx Tahoe City after that,” Koijane says. “It was our way of trying to look out for our community and well-being of people given our unique paradigm in Tahoe for extreme sports activity and the deaths that happen around that.”

As the mother of two boys—now 14 and 17 years old—Koijane says parents of children in Tahoe have different concerns about child safety than parents elsewhere: “It’s a strange thing. It’s unique to these mountain towns.”

Robb, too, has a unique perspective, Koijane says, noting that his work with Sportgevity and other programs springs in part from his ability to see things that aren’t apparent to many other people. She describes it as an ability to connect dots that are a little farther apart than normal, to the point that a connection might not be obvious at all.

“I don’t know if we made a difference,” she says. “Maybe we did, temporarily.”

Robb sometimes ponders reviving the effort that he hoped would make a national difference, but admits the project got sidetracked when someone started trying to build a rollercoaster in his backyard.

Big Developments

Tom Mooers met Robb during what the executive director of Sierra Watch describes as a “tumultuous time in Tahoe” after a group then known as KSL Partners bought the ski resort then known as Squaw Valley and “threatened to transform Tahoe with development of a size, scale and scope that the region had never seen.”

Plans included tall buildings, an indoor water park and an amusement park–style ride.

“It was at the time Sierra Watch was embarking on this mission to—as we called it back then—‘Keep Squaw True,’ and Robb stepped up as a leader in that effort,” Mooers says. “And that’s when I first got to meet him.”

Mooers explains that his group was building a movement thousands of people strong based on a shared love of the mountains.

“Robb was already an important and prominent leader in the community,” Mooers says. “His willingness to step into a leadership role in this blossoming movement? It really took a lot of courage, because there was a lot of divisiveness and rancor.”

In other words, putting his face and name out there in such a prominent way essentially painted a target on it. Mooers says when Robb took that step, he created a safe space for others to do the same. As a result, thousands of Davids countered their targeted Goliath with a movement that ultimately became known as Tahoe-Truckee True. Scott and Robb collaborated again on another film: 2018’s The Movie to Keep Squaw True.

In July 2022, Sierra Watch secured a court order for Placer County to overturn or rescind all approvals it made in relation to the development in 2016. Mooers says even though their efforts have been successful thus far—“I was in Olympic Valley yesterday, and there’s no indoor water park”—they know it’s not over. He does, however, credit Robb with playing an indispensable role in proving, “We don’t have to accept it. We can demand better for our mountains.”

Now, while he obviously fields questions about the future of Tahoe, Mooers says a lot of people ask him about Robb, who stepped back from appearances in recent years.

“He’s definitely very famous in a certain part of our culture—and not without reason,” Mooers says. “He is a celebrity, and he has to some extent—as he’s been dealing with the challenge of staying alive—he has pulled back out of the limelight a little bit.”

Robb Gaffney above Tahoe’s East Shore in January 2015, photo by Matt Bansak

A Change Inside

In July 2019, Robb was diagnosed with a high-risk form of myelodysplastic disorder, a type of bone marrow cancer considered a precursor to leukemia.

Scott remembers his brother first noticing symptoms of something wrong, as well as calling when he learned that cancer was the culprit. Scott was with their parents back East, where there was much crying and passing the phone around, he says.

From October 2019 to February 2020, Robb stayed at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston for his first stem cell transplant. That February, he had a relapse, and the cancer progressed to an aggressive form of acute myeloid leukemia. In August 2020, he had his second stem cell transplant at UC Davis, which quieted things down for a while.

In June 2022, his doctors discovered a recurrence, which puts him on a path for lifelong monthly infusions to keep the cancer from growing more—a treatment that seems to be working so far.

“Cancer is a wild experience, and it brings us into wild places and our mind does some wild things,” Robb says of his journey and the realizations that prompted his current writing project. “Much of our ability to cope better comes from understanding it can be a wild ride, and that the wild ride is normal.”

Truckee resident, teacher and founding member of the Public Art Commission Jean Fournier says when she found out she had a rare blood cancer in October 2021, “Everybody in the community said, ‘Talk to this guy, Robb.’”

When people are diagnosed with more common or known cancers, she says, there’s more public familiarity with what treatment and recovery look like. While she describes the local center as amazing, especially for a rural area—offering yoga, psychiatric help, art and caregiver groups, all free of charge—she jokes that there’s a big group for prostate cancer, but not for her.

“Bone marrow and stem cell transplants? Most people don’t understand,” she says.

Facing an uncertain future and wondering where to find community, Fournier took her friends’ advice and sought out Robb.

“He was a guidepost for me,” she says, describing him as speaking the language of rare bone cancers in a way even her own family members couldn’t. “He was really one of the few people who knew what I was going to go through.”

How did they connect? Through long walks, of course. They bonded over their shared love of the mountains—something bigger than their cancer.

Fournier had a bone marrow transplant in April 2022 and has been recovering on medical leave since. She admits that her journey was relatively quick in some ways, but that doesn’t mean it was easy. When she couldn’t have visitors, Robb and his wife, Andrea, stood in the parking lot and waved at her.

“He’d been right there on that floor,” she says, adding that he told her she would be “doing the same for someone down the road many years from now.”

With Friends Like These

Todd Offenbacher describes himself as “quite retired” after working 23 years as a TV host for Outside Television. Now, he considers himself a “bipolar ski guide”—in that he leads expeditions to both the Arctic and Antarctic. He’s also a director of the Sierra Avalanche Center, creator and host of the Tahoe Adventure Film Festival, and an avid rock climber, skier, adventurer and traveler.

“I’m pretty strong,” he says. “[Robb] still can kick my ass, even with the cancer.”

Fresh off his first stem cell transplant, Robb Gaffney skis the Mount Rose backcountry in March 2020, photo by Matt Bansak

Offenbacher says he doesn’t remember exactly where they met—“probably some social thing on the North Shore, maybe a Matchstick movie premiere”—but he now numbers Robb among his favorite people in the world: “He’s kind, he’s athletic, he’s a great friend—and supportive. He just kind of checks all the boxes. He makes me want to be a better friend, a better person in the community.”

He adds: “Robb’s kind of that guy who every day is trying to figure out how he’s going to make his day the best he can. The other thing? How he’s going to make either the community or the world better that day.”

Kirk Ditterich is a clinical psychologist who saw Robb in a ski movie where they called him “the doctor.” After learning that the title was legitimate, Ditterich decided to see if he could complete his postdoctoral hours with the legend.

“I was like, ‘That’s never going to happen. There’s no way I can live in Olympic Valley and do my post doc with the famous skier,’” Ditterich says.

Still, he called Robb out of the blue and got a response three months later: “Yeah, come on down.”

Ditterich admits he was expecting a “dude who’s gnarly and, you know, going for it all the time. … I was expecting Shane McConkey that was an MD. I love that he just busted that mold for me.

“I got here, and he’s this gentle and loving soul and was just perfect for what I needed for my postdoctoral work.”

Robb emphasized connecting with patients over writing notes—a strategy that helped Ditterich ultimately obtain his license and land a job as a psychiatrist at a local medical center.

“Ten years later, here he is a patient here,” Ditterich says, adding that he doesn’t work with Robb clinically.

Reflecting on Robb’s influence, Ditterich comments on everything from their times skiing together, to seeing the way Robb deals with his kids and is committed to his wife, to learning the importance of balancing his professional and recreational lives.

Robb Gaffney enjoys a special day of skiing with his daughter Kate on the East Shore of Tahoe in January 2021, photo by Matt Bansak

Tomorrow and Beyond

Kate Gaffney is outdoors.

The UC Berkeley sophomore does have to spend time inside working on her cognitive science degree and data science minor—preferably with the Lord of the Rings trilogy playing in the background—but she leaves four walls and a roof behind whenever she can. Frequently, that means heading out with her dad.

“Starting from when I was super young, the outdoors has always been our way of connecting,” she says. “He was really the one that introduced me to the outdoors, which is one of the biggest parts of my life now.”

Ultimately, Kate says she feels like she was able to grab onto that passion and find what she really likes to do when it comes to being outside. She attributes her outdoor enthusiasm to her dad’s encouragement, which she likens to a push forward “in the most beneficial way”—a sentiment echoed by virtually everyone interviewed for this story.

Robb has been there, Robb continues to be there with a gentle hand on the back, a word that inspires someone to take the next step, and the one after that, and the one after that, all toward a better future.

“One really cool characteristic about Robb is that he loves sharing what he loves to do with other people,” Scott says. “He wants them to have the same experiences that he has had. … He sandbags a lot people, gets them in over their heads. We actually have a word for it.”

“It’s getting ‘Robbed,’” Kate jokes. “He would be like, ‘Just to that next tree!’ … ‘Just to that next lookout!’ … He always wants to go to the next point. … I feel like my brother and I have followed in that lead a little bit—or at least tried to follow in his footsteps because he has this awesome way of being outside.”

Kate says they have several activity goals, including backcountry skiing in the Mammoth area.

“I really think that how my dad introduced me to the outdoors has been one of the most, if not the most, beneficial things in my life. The past few years, some of the most special and rich moments have been with my dad outside, especially after his treatment. … Once he got better, we’ve had a lot of teary moments sitting on top of mountains. I’m super grateful, more than words can express, to still be able to do things with my dad after everything he’s been through.”

That “everything” encompasses a lot—not just cancer, but the triumphs and pride of raising a family and the heartache of seeing friends fall and not get up. It’s carving a name for himself in a niche sport and stepping away to pursue a career. It’s working to build and inspire a community to be the best it can be, and then watching that community reflect the love and support back when needed most.

Ultimately, Robb’s approach to skiing and navigating the challenges of life blur together—but when you’re viewing it all through a curtain of softly falling snow, realizing you are exactly where you want to be, enjoying it with the people you want to be with, does it matter?

“In the end, if you do it right, you remain standing,” Robb says. “You can look back up and appreciate what you just came down.”

Ryan Miller is a writer who lives in the Sacramento area. Follow him on Twitter or Instagram, @jesteram.

No Comments