30 Nov Strange Tales From the Toiyabe

A backcountry snowboarding adventure in the Arc Dome Wilderness inspires a reflection on some unusual history in a remote Nevada mountain range

The washboard-infested road demands attention, but I can’t help but stare in the rearview mirror. The eastern horizon is on fire with the last rays of sunlight. Crimson clouds hang above a dramatic mountain crest glowing in bubblegum pink light.

The sight is particularly satisfying as Arc Dome, the 11,780-foot-tall high point of Nevada’s Toiyabe Range, sits dead center of view out the back window. My wife Allison and I have just climbed Arc Dome and ridden our snowboards off the summit. Now driving home to North Lake Tahoe, we are still basking in the thrill of the day’s adventures.

We drove the 200 miles from Lake Tahoe to the Arc Dome trailhead the day before, and from the minute we left the journey felt improbable. Our previous questions about how to access the peak have now been answered, but newly hatched butterflies of curiosity now flit between our ears. Wonders about what road to take to the trailhead, or which drainage to climb to the summit ridge, have been replaced with even more intriguing questions about what we saw on our backcountry snowboarding tour.

Looking out to the Big Smoky Valley, Allison Lightcap drops into the seldom-ridden east face of Arc Dome in Nevada’s Toiyabe Range, photo by Seth Lightcap

Venturing into the Toiyabe

Rising over 5,000 feet above the sagebrush, near smack dab in the center of the state, the 120-mile-long Toiyabe Range is Nevada’s second longest mountain range. America’s “Loneliest Highway,” U.S. Route 50, crosses the northern end of the range at the historic mining town of Austin, and the town of Tonopah is 30 miles south of the Toiyabe. The crest of the range rarely drops below 10,000 feet for nearly 90 miles, allowing the Toiyabe to collect a substantial snowpack most winters.

But while the lingering spring snowpack has drawn us to the Toiyabe this day in April 2021, what piques our interest on our tour has nothing to do with snowboard descents. As we drive along the windy gravel road, stealing a few last glimpses of Arc Dome in the mirrors, we are deep in conversation about the unusual signs of human activity observed throughout the day.

Our hike began at the Columbine Campground on the west side of the range. The campground is the primary trailhead for the Arc Dome Wilderness, a protected area spanning nearly 120,000 acres at the southern end of the range. Soon after leaving the campground, we toured into one of the biggest aspen groves we’d ever seen. Seemingly every tree was covered in drawings and Spanish phrases carved into the bark. The next oddity were the remnants of stone walls on Arc Dome’s summit that did not look like typical hiker wind shelters. Then, on the way out, we came across some odd rusty metal that we assume was from a mining operation. Or was it?

All these observations swirl in our heads as we begin the drive home, where some Googling in the following months reveals answers that are both interesting and unsettling. As it turns out, the history of the Toiyabe Range holds a few thought-provoking and lamentable tales.

Carving Away the Time

From our travels in the Sierra, we have seen many aspens with words and images carved into their trunks, including several groves in the Tahoe area. The carvings, known as arborglyphs, represent the work of Basque sheepherders.

Arborglyphs on an aspen deep in the Toiyabe Range, photo by Seth Lightcap

The Basque people, native to what is present-day Northern Spain and Southern France, started immigrating to the American West in 1850 during the California Gold Rush. Many of them had worked on farms, and thus became known for their expertise in ranching and handling livestock. These immigrant sheepherders, who spoke no English, ventured into mountain ranges with only basic survival gear, a horse and a herding dog and were tasked with moving thousands of sheep across the land by themselves during the summers. It was lonely work and many of the herders took to carving on aspens to pass time and mark their presence in an area.

What’s surprising in the aspen grove near Arc Dome is the sheer number of carvings and the range of dates. They include Spanish phrases and names dating from 1915 all the way to 1985. The Toiyabe Range clearly has a long history of Basque sheep herding activity.

Kirk Peterson, research coordinator with Friends of Nevada Wilderness, is a historian who has spent 30 years traveling the back roads of the Great Basin collecting experiences and stories about Nevada’s many mountain ranges. Peterson’s research on sheep herding in the Toiyabe turned up some astounding figures that reflect the massive gallery of carvings in the grove.

Peterson found reports of nearly 100,000 sheep being driven the entire length of the Toiyabe Range in the summer of 1907.

“Grazing followed right on the heels of the mining boom in the Great Basin,” says Peterson. “Mining camps created a huge demand for food, and many realized that they could make more money grazing animals and selling the meat than they could digging for silver or gold.”

The Basque sheep herding operations at the turn of the twentieth century took advantage of the lax oversight of public lands at the time. Herders would take as many sheep as they could handle into the mountains and graze them anywhere that held grass.

The federal government cracked down on unregulated grazing on public lands by designating mountain ranges like the Toiyabe as National Forest lands under the management of the U.S. Forest Service. The Forest Service then divided the land into grazing allotments and issued limited permits for each allotment that specify how many cattle or sheep are allowed to graze in a given area.

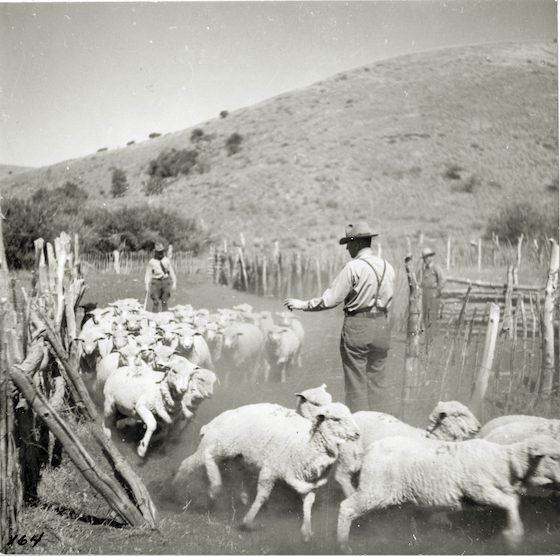

Sheep grazing in the Toiyabe Range started in the 1880s. Roughly 100,000 sheep roamed the range each summer by 1911, photo courtesy Nevada Historical Society

This Forest Service grazing permit program is still in place, and like many ranges in Nevada, every acre of the Toiyabe is included in a grazing allotment. But of the 20 total allotments in the Toiyabe, 15 are actively grazed, four are closed and one is vacant.

Lance Brown, district ranger of the Austin-Tonopah District of the Humboldt-Toiyabe National Forest, oversees the grazing program in the Toiyabe. In 2022, Brown issued grazing permits for a total of 2,848 cattle and 6,700 sheep spread over the 14 active allotments—a fraction compared to the number of livestock that used to roam free in the range.

Brown feels the current amount of grazing in the Toiyabe is sustainable and says numbers will continue to be adjusted to climatic conditions.

“We are adjusting annual grazing numbers based on our extended drought in the Great Basin. Most allotments have been reduced to account for the fact that less moisture means less plant growth,” says Brown, adding that there will be no new aspen carvings from Basque sheepherders in the Arc Dome wilderness.

“The four closed allotments in the Toiyabe Range are all within the Arc Dome Wilderness,” he says. “Per our forest plan, we won’t ever consider opening those allotments to grazing again.”

Don’t Drink the Water

The day we climb Arc Dome, the morning starts cold. We are bundled up when we leave the trailhead and the firm snow makes for fast travel from the lower forests into the alpine. As we climb onto the rocky ridgeline and into the direct sun, the temperature warms, motivating us to shed layers and guzzle water.

Our ascent route requires us to gain the crest of the range, then drop into a deep drainage on Arc Dome’s north side before climbing up the north face to the summit. We make our first turns of the day, riding a halfpipe-like gully that pours into a creek drainage that abruptly ends in a small waterfall.

As we switch our splitboards back to tour mode after the descent, we are tempted to fill our water bottles in the creek, but after a quick debate we decide against it. We did not bring a water filter, so better to conserve what clean water we have than roll the dice on getting sick.

Our rationale is based on the assumption that either grazing or mining operations have polluted the water sources in the range. What we later learn is that not only are there elevated levels of giardia, mercury and arsenic found in Toiyabe waterways, there are potentially even more dangerous water pollutants lurking.

From January 1951 to July 1962, during the height of the Cold War, the United States Atomic Energy Committee conducted 100 nuclear tests at a site in south-central Nevada known as the Nevada Proving Grounds. The site is only 65 miles north of Las Vegas and 120 miles south of the Toiyabe Range. The first nuclear test blew out storefront windows in Las Vegas, and it is well documented that every test conducted released significant radioactive material into the atmosphere.

How much nuclear fallout drifted downwind of the test site and contaminated the soil, water, animals and people of the Great Basin has been studied and questioned for the last 70 years. Study results have varied. Some tests found elevated radiation levels, some did not.

Bonnie Bobb, a cross-cultural psychologist and environmental consultant who specializes in Native American issues, conducted a study in 2008 that tested for radioactive isotopes in 36 soil samples collected from around the Toiyabe Range. The study was funded by a Department of Energy grant and completed on behalf of the Yomba Shoshone Tribe, who live on a reservation just west of the Toiyabe Range in the Reese River Valley.

The Yomba people have suspected that their homeland was contaminated by fallout from the tests as they have faced higher than average rates of cancer and miscarriages in their community.

“I took 36 soil samples from around the area, and I figured I would pick up radiation in at least one,” says Bobb. “I found radiation in all 36 tests, and the most contaminated samples were in the mountains.”

Bobb tested the soil samples for radioactive isotopes that are rarely naturally occurring, but are known byproducts of nuclear weapons testing, such as cesium-137, plutonium-239/240, strontium-90, americium-241 and tritium.

All these radioactive contaminants are attributed to increased cancer risk, and other communities downwind of the test site, such as St. George, Utah, have also seen elevated cancer rates linked to the testing.

“Nuclear radiation from the tests did not come down in just one location,” says Bobb. “It fell in varied locations based on the cloud cover and the winds, and you can’t pinpoint exactly where that was.”

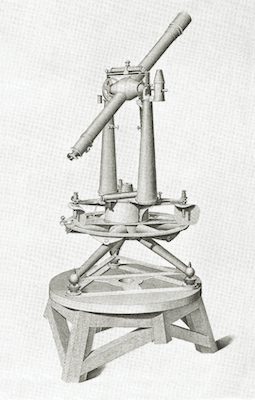

In the 1880s, Arc Dome was home to a U.S. Coast and Geodetic Survey station where they used a telescope-like device called a theodolite to survey the Great Basin, photo by Seth Lightcap

The Triangulation Station

The last few hundred feet of climbing to reach the summit of Arc Dome demands strapping our snowboards to our backpacks and hiking over discontinuous snow patches and loose rock. When we gain the summit ridge, we find the hiking trail used to climb Arc Dome in the summer. Following the trail a short way to the summit, we come across a couple of partially melted out, obviously man-made rock structures. The structures don’t look like your average stacked-rock wind walls built to catch a break from a cold breeze. They look like the remnants of laboriously crafted rock-walled shelters carved into the summit plateau.

Our attention quickly drifts from the rock structures as we soak in the epic view and begin preparing to ride one of the steep chutes that drops off the summit. Our plan is to descend into the basin on the east side of the peak, then climb back to the ridge at a lower saddle to begin retracing our route back to the trailhead.

The descent is a blast as the snow is perfectly sun-softened, and the views out into the Big Smoky Valley are phenomenal. The skyline is stacked in every direction with mountain range after mountain range.

An instrument known as a theodolite was used atop Arc Dome for surveying in the nineteenth century, courtesy photo

We are definitely not the first to remark on the stunning views from Arc Dome.

The rock structures were built in 1880 by a National Geodetic Survey crew, which was tasked by Congress to accurately measure the size and shape of the nation from coast to coast with corrections made to account for the curvature of the earth. To conduct the survey, mountains were chosen that lined up in a system of triangles along the 39th parallel. Employing principles of trigonometry, distances between the mountains were calculated by measurements from the summits using a signaling device called a theodolite. Resembling a telescope, the theodolite featured small, adjustable mirrors designed to catch sun rays and reflect them to observers in the distance. Altitude, latitude and longitude of signaling sites could be determined by taking thousands of measurements and averaging the results.

Arc Dome was chosen as one of the central triangulation points in the Great Basin as it offered an unrivaled view. Signaling from summit to summit on a clear day, the reflections could be seen up to 150 miles away. To facilitate the work, a triangulation station was built on Arc Dome’s summit to house the workers while they conducted the survey over several years. The rock structures atop the peak are the last vestiges of the station.

Not Your Average Rusty Relic

After our descent down Arc Dome’s east face, we make a traversing climb back to the ridge and then drop into a west-facing drainage that provides access to the high plateau above the trailhead. Climbing up the drainage after the descent, we come across what looks like a pressurized air tank and some kind of engine smashed into the bottom of the creek bed. They are unusual sights, but Nevada is full of rusty metal, so we don’t think much of it.

An engine high in the Toiyabe Range may be from a military plane crash in 1945, photo by Seth Lightcap

Upon gaining the plateau, we walk across a scree field that we hope is the final dry hiking stretch before a long descent down a snow-filled drainage back to the trailhead. The rocks in the scree field are quite uniform in size and shape, so we notice several more oddly shaped chunks of metal poking out from the sea of choss. But once again, we aren’t interested in the rusty relics of whatever it is. At that point, we are ready for the snacks and cold beverages waiting at the truck.

Had we known the likely origin of the metal on the plateau, and the air tank in the creek, we might have taken a second look. As we later learned, we had come across the debris field from a military plane crash in 1945.

The plane was a B-24 Liberator bomber from World War II. Upon returning from Europe, it was being transferred to the West Coast to potentially be used in the Pacific.

The B-24 was scheduled to land at Tonopah Army Air Base on August 3, 1945, but never made it. The plane is believed to have encountered an unexpected storm over the Toiyabe Range, lost visibility and then dropped elevation too quickly thinking it was approaching Tonopah. Tragically, it slammed into the 11,000-foot rocky plateau that we walked across, killing all three servicemen on board.

Maverick Moves

On our descent down the exit drainage, we finally have the real estate to open it up and rip huge turns on our snowboards. The bowl pours into a low-angle meadow, so we barrel into the flats at top speed, blasting past sagebrush patches and negotiating rogue boulders as if out-maneuvering enemy fighter jets in a dog fight like Maverick and Phoenix from Top Gun.

We safely navigate a few sections of thin snowpack and are soon coasting down the final stretch of trail to the truck. It’s been a quintessential day in the Nevada wilderness that we will not soon forget, especially when reminded of the beauty of the Toiyabe Range by Hollywood blockbusters.

The recently released Top Gun: Maverick includes a dramatic fighter jet training scene where Maverick, Tom Cruise’s character, flies through a twisty desert canyon at top speed and hits the bullseye on a practice target with a missile. The scene was filmed in Kingston Canyon in the Toiyabe Range just a few miles north of Arc Dome. For two days in July 2019, the Top Gun production crew posted up in the canyon and filmed U.S. Navy fighter planes piloted by real-life Mavericks with ultra-high-resolution IMAX 6K cameras.

Gotta love when life is like the movies. Too bad we can’t go Mach 10 on our snowboards like Maverick. That would be fun.

Seth Lightcap is an Olympic Valley–based writer, photographer and avid explorer of Sierra rock, snow and trail.

No Comments