02 Jul Ancient Waters

A professor’s research puts Tahoe on the podium of oldest lakes in the world

Rocks are not widely recognized for their storytelling abilities, but the account of Lake Tahoe’s formation is written in stone if one knows where to look.

A slanted stretch of rock formations at Commons Beach in Tahoe City, the white chalky remnants of ancient single-celled algae at Skylandia Beach west of Dollar Point and the former volcanic vent now known as Eagle Rock on the West Shore are small pieces of a puzzle that recently helped clarify Lake Tahoe’s standing among the earth’s oldest lakes—and generated worldwide attention in the process.

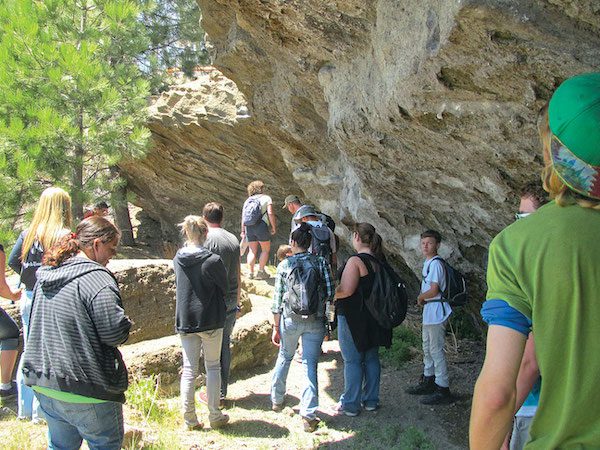

Dr. Winnie Kortemeier educates students about the geology of the 2.3-million-year-old tuff cone at Commons Beach, courtesy photo

The geological features factored into research by Western Nevada College geosciences professor Winnie Kortemeier for her 2012 PhD dissertation on the volcanology and geochemistry of volcanic rocks in the northwest part of the Tahoe Basin. Her research determined Lake Tahoe’s age to be at least 2.3 million years old. More than a decade later, the dissertation attracted renewed attention in fall 2024, when a literature study by Kortemeier found that Lake Tahoe is the third oldest permanent freshwater lake in the world, and the oldest in North America.

An article written by Western Nevada College on the new findings was picked up by numerous outlets, including England’s Daily Mail. The college’s media monitoring service estimates the article reached 126 million people in 2024 alone.

“I was famous for two weeks, and you missed it,” Kortemeier says, recounting how she jokingly relayed the media blitz to friends.

Master of Geology

Kortemeier says she was thrilled that her research received so much attention, but it’s not dissimilar to the work she’s undertaken at Western Nevada College for the past 36 years. Getting people with little exposure to the earth sciences excited about the natural world is a key piece of her job’s allure.

“I’m always trying to share stories of the geology or the geography,” Kortemeier says. “Rocks, mountains, lakes—they all have stories to tell, and it’s the stories that help students connect to science.”

On field trips, Dr. Kortemeier enjoys asking the students to critique the information plaque at Commons Beach before revealing that she wrote it, courtesy photo

Kortemeier has thrived in her role, in part, by taking science education out of the classroom and into the field, passing on lessons from mentors like U.S. Geological Survey volcanologist Jim Moore and retired University of Nevada, Reno geology professor Rich Schweickert to new batches of students each semester.

Having Lake Tahoe—where geology takes on a scale that’s harder to ignore than rocks in boxes—as an easily accessible field study area is a blessing for a geoscience professor, Kortemeier says. The regular visitor to Tahoe can never quite turn off the geologist part of her brain, even when she’s off the clock.

“I’m always seeing something new about the rocks. It’s terrible,” Kortemeier says with a laugh.

Kortemeier’s inspiration for her dissertation came during a 2005 field trip led by Schweickert that included a visit to Skylandia Beach. On the trip, she learned there was a dearth of information on the volcanic rocks on Lake Tahoe’s northwest shore. Recognizing the presence of palagonite, a mineral formed when basaltic lava flows interact with water, she knew she had knowledge that could answer questions about Lake Tahoe and the volcanic rocks that had interacted with it. She volunteered to undertake the research.

“It was crazy because I was committing seven years of my life,” Kortemeier says.

Lake Tahoe Origins

As part of that commitment, Kortemeier mapped the volcanic rocks from Dollar Point to Eagle Rock and, with the assistance of the U.S. Geological Survey, was able to determine the ages of several samples using radiometric dating.

The resulting work detailed the timing of lava flows from small volcanoes in the area and their interactions with the pre-existing shallow lake water. While the lava flows didn’t create the Tahoe Basin or the lake itself—that can be attributed to earthquake faults running underneath the Basin continuously dropping the bottom of the lake as it filled with rain and snowmelt—they did create rock features reminiscent of those found in Hawaii.

Volcanic lapilli tuff at the Tahoe City quarry offers a glimpse into Tahoe’s ancient past, courtesy photo

“This study documents a spectacular set of hydrovolcanic features formed when Pleistocene volcanic rocks erupted and/or flowed into an ancestral lake called Proto-Tahoe [early shallow Lake Tahoe] and, in some cases, interacted with wet sediments,” according to Kortemeier’s dissertation. “Some of the lava flows crossed Proto-Tahoe shorelines and quenched beneath water.”

The paper documents three cycles of Truckee River Canyon damming via these lava flows—one at 2.3 million years ago, one between 2 and 2.1 million years ago and one at 920,000 years ago. Each of the episodes took place near Rampart, in the Truckee River Canyon between Tahoe City and River Ranch, and raised the lake level before the lava rocks would eventually erode and bring the lake level down with it.

“Tahoe was up to 186 (meters) above present lake level,” according to the dissertation. “Yet even with fluctuating lake levels, it appears that the outlet of Proto-Tahoe/Lake Tahoe has been near its present position in the Truckee River Canyon since 2.3 (million years ago).”

Embracing Old Age

Kortemeier always figured a researcher would come along and put the lake’s 2.3-million-year-old history into proper perspective with other lakes around the world. But ultimately, she would have to undertake that work herself.

During a sabbatical between 2023 and 2024, Kortemeier reviewed the available verified information on lakes around the world and determined Siberia’s Lake Baikal, at 5 to 10.3 million years old, and Africa’s Lake Tanganyika, at 8 to 10 million years old, are the only lakes that predate Tahoe.

All three lakes are in fault-controlled basins, where earthquakes continually lower their lakebeds and keep them from succumbing to the fates of many of their counterparts—filling with sediment and disappearing. (Such was the case with Sierra Valley north of Truckee, which was once a 180-square-mile, 1,500-foot-deep body of water known as Lake Beckwourth before it filled in with sediment over the millennia).

The characteristic portends a bright future for Lake Tahoe on a geological timescale.

“For the foreseeable millions of years into the future, Tahoe will keep getting deeper,” Kortemeier says.

As for her, the professor says she has no plans for a follow-up study but will continue to pursue her passion for connecting people with science. Kortemeier occasionally speaks to audiences outside of Western Nevada College—she led a lecture at the UC Davis Tahoe Science Center in Incline Village in June—bringing her love of geology to those interested in hearing the stories rocks have to tell.

“That was my big hoorah,” she says of her 2024 research. “I’ll keep teaching. I’ll keep telling stories.”

It’s hard to retire when you find yourself with more energy at the end of class than at the beginning, Kortemeier says. Being able to take students into the field and having Lake Tahoe as a classroom are also great ways to keep a professor going.

“If I couldn’t keep up with my students on field trips, maybe it would be time to pass it on to someone else,” Kortemeier says. “But not yet.”

Adam Jensen is a former Tahoe-based reporter who now lives in Modesto.

Cecilia Gregg

Posted at 14:44h, 22 JulyKudos on your research and findings, Winnie! There are so many amazing geological topics to study in the region and I’m so proud that you are supporting our community with your work! Keep it up!