25 Jun The Bravest of All Mountaineers

Nearly decimated by the settlement of the West, bighorn sheep in California and Nevada face a complex fight to regain their historic stomping grounds

At ease above exposure, a Sierra Nevada bighorn ewe searches for her next grassy meal, photo by Steve Yeager

Humans love to consider themselves “king of the mountain.” But the claim is really just an ego trip.

The true king of the mountains in North America is without a doubt the bighorn sheep. Watch a bighorn climb a steep mountain slope, and you’ll see why. Bighorns waltz across narrow cliff ledges and prance up rock slabs like no other animal. Their deft footwork and fearless gait traveling through loose, rocky terrain is a true wonder of the natural world.

Wearing a crown of thick, curved horns and dressed in a regal coat of caramel brown wool, a bighorn is a stately sight to behold even when standing still. Human reverence to these magnificent ungulates began with the Native Americans who worshiped them as a sacred animal and hunted them as an important food source.

Early Western explorers were equally impressed by the bighorn’s talents. John Muir witnessed unbelievable bighorn climbing feats in his High Sierra travels and proclaimed them “the bravest of all the Sierra mountaineers.”

Reminiscing on watching a herd of bighorn seemingly levitate up a rock cliff, Muir wrote in his book The Mountains of California, “This was the most startling feat of mountaineering I had ever witnessed, and, considering only the mechanics of the thing, my astonishment could hardly have been greater had they displayed wings and taken to flight.”

While bighorns have likely never lived in the Tahoe Basin, they are native to the Sierra south of Sonora Pass and almost all the desert mountain ranges in Nevada and Southern California. Prior to the start of the California Gold Rush in 1848, nearly 50,000 bighorns were estimated to live in California and Nevada, plus another 150,000 throughout the rest of the Western United States, Western Canada and Northern Mexico.

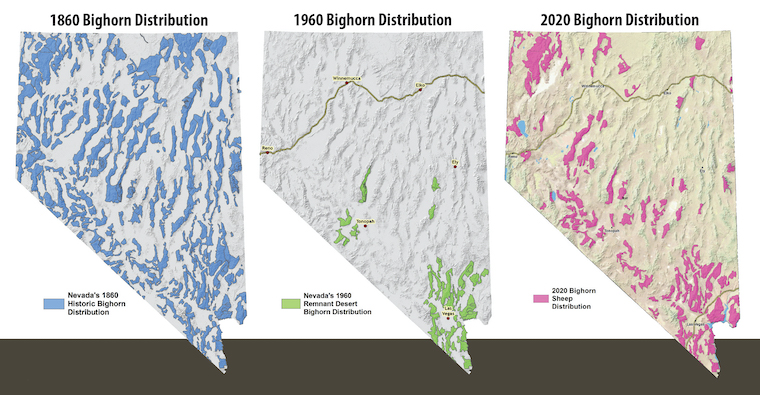

But flash forward a century, and it is clear why bighorns are a rare sight in California and Nevada today. By 1960, regional bighorn populations had been slashed from 50,000 to barely 5,000. Unregulated hunting, habitat destruction and, most predominantly, diseases contracted from domestic sheep had unceremoniously toppled the king of the mountain West.

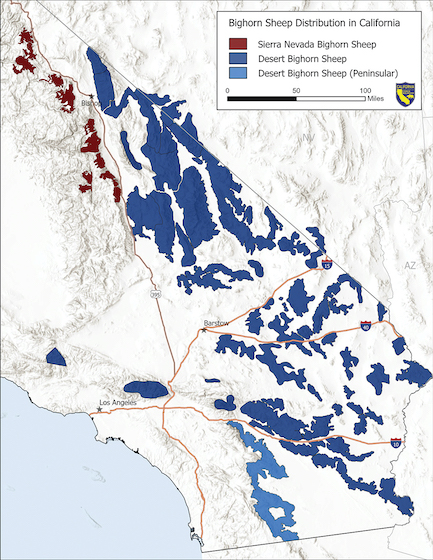

While the animals were completely extirpated from states like Oregon, Washington and Colorado, the only reason bighorns are still found in this region is thanks to heroic conservation efforts that were enacted in California and Nevada in the last 50 years. Because of these efforts, an estimated 15,000 bighorns now live in California and Nevada again, although they occupy significantly fewer mountain habitats than they once did.

A Sierra Nevada bighorn ram stands guard over a herd of ewes during the fall mating season, photo by Steve Yeager

From Siberia to the Sierra and Beyond

While both successful overall, the paths conservationists have taken to save the bighorn have been substantially different. The diverse strategies reflect the complex conservation challenge bighorns present as a threatened species.

Few know the history and future of local conservation work better than Dr. John Wehausen, a renowned bighorn researcher from Bishop, California, who has studied bighorn sheep in the Western U.S. for over 45 years.

Wehausen dedicated his life to bighorn conservation, first as a graduate student for the University of Michigan and then a researcher for the University of California’s White Mountain Research Station, and now as the president of the nonprofit Sierra Nevada Bighorn Sheep Foundation.

What makes bighorns so special is also what makes them such a tricky species to rescue, says Wehausen: “Conservation-wise, they are a major challenge because they naturally live in small, geographically isolated populations, which makes them very vulnerable to introduced diseases and predation.”

Bighorns’ predisposition for living in small populations at high altitudes stems from their ancestry. They are descendants of Asian snow sheep that crossed over the Bering land bridge from Siberia to Alaska nearly a million years ago. Evolving in response to their new habitats, the snow sheep diverged into the two species of mountain-dwelling sheep still found in North America today—Dall sheep, which are native to Alaska, and bighorn sheep, which are native to the Western U.S., Canada and Northern Mexico. From there, bighorn sheep diverged again into three genetically distinct subspecies—Rocky Mountain bighorn, desert bighorn and Sierra Nevada bighorn.

Rocky Mountain bighorns are the largest of the three subspecies, with mature rams weighing up to 300 pounds. Sierra Nevada and desert bighorns are slightly smaller on average, with mature rams weighing up to 220 pounds. Skull size and horn structure also differ between the three subspecies. The horns of Rocky Mountain and desert bighorn rams form tighter curls than those of Sierra Nevada bighorns.

Two of the subspecies are native to California, as desert bighorns took up residence in mountain ranges throughout Southern California, and the Sierra Nevada bighorn evolved as a unique subspecies found only in the Sierra. Desert bighorns were the only subspecies native to Nevada, but the state is also now home to Rocky Mountain bighorns, which were historically only native to Canada.

Wehausen has spent the majority of his career studying the Sierra Nevada bighorn, but his genetic and morphological research on all three subspecies has had a major influence on bighorn conservation work throughout the West. His work ushered in a new era of understanding about the bighorn that began with early conservation measures adopted in both states 150 years ago.

A geographical timeline of bighorn distribution in Nevada, courtesy Nevada Department of Wildlife

Battling Bullets, Bugs and Bacteria

Nevada was the first to recognize the bighorn’s troubling fate in the face of Western pioneers. In 1861, the state made its first management move by outlawing bighorn hunting between January 1 and July 1. Forty years later, in 1901, bighorn hunting was banned all year in Nevada and remained forbidden until 1952. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service also created the Desert National Wildlife Range in Southern Nevada in 1936, further protecting several desert bighorn herds.

California followed Nevada’s lead in 1878 by banning bighorn hunting. At the time, it was believed that if wildlife was protected from hunting, it would quickly recover and recolonize former ranges. But in reality, the regulations were too little, too late. Bighorns had already disappeared from dozens of former habitats, and they are naturally slow to recolonize. Hunting was also not the primary cause of bighorn deaths. The animals weren’t losing the battle to bullets, they were being decimated by disease.

By the late 1800s millions of domesticated sheep and cattle were grazing on federally owned land in California and Nevada. The domesticated sheep could handle rugged terrain, so they were brought to graze in mountain valleys that the sheep herders could readily access. The grazing led to inevitable contact between the domesticated and wild bighorn sheep.

One hundred years later, Mike Cox, the Nevada Department of Wildlife’s game biologist specializing in bighorn sheep and mountain goats, is still dealing with the devastating result of this interaction between bighorns and their domesticated relatives.

“In the early 1900s there wasn’t a mountain range outside of the Mojave Desert that didn’t have hundreds of thousands of domestic sheep,” says Cox. “Sheep are naturally gregarious, so there was contact between the species, and the bighorn’s immune system was totally naive to the suite of bacteria that the domestic sheep were carrying.”

Scabies and pneumonia-causing bacteria from the domestic sheep quickly spread throughout the bighorn herds, causing massive die-offs. While some adult bighorns were able to fight off the pathogens, they remained carriers of live infections and spread the diseases to their young, whose immune systems weren’t fully developed.

“When all the babies die, there is no way to cover for adult mortality, and the herd is doomed,” says Cox.

Between 1870 and 1960, the spread of diseases spawned from domestic sheep killed thousands upon thousands of desert bighorns in Nevada and extirpated them from dozens of their former habitats. The only places bighorns survived in Nevada were on what Cox calls “sky islands,” mountainous regions so dry, hot and inhospitable that no domestic sheep herder would graze there.

The early effects of disease on Sierra Nevada bighorn populations in California were equally devastating. Before the Gold Rush, it is estimated that there were only 1,000 Sierra Nevada bighorns living in fewer than 20 populations. Hundreds of these bighorns were lost to scabies and pneumonia around the turn of the century, including all the wild sheep that had previously been found within Yosemite National Park. The state responded by implementing grazing reductions to help protect the Sierra bighorn starting in the 1930s, but the grazing conflicts continued into the 1960s.

A desert bighorn lamb near Walker Lake, Nevada, photo by Dwayne Hicks

Early Success and New Adversaries in the Sierra

By 1960, Nevada’s desert bighorn sheep population had dwindled to fewer than 3,000, with most of the survivors in the mountain ranges around Las Vegas. Meanwhile, bighorn sheep north of Highway 50 had been eliminated by disease, while desert bighorn populations in Southern California were reduced to fewer than 1,000, and Sierra Nevada bighorns numbered fewer than 300.

Despite the rapidly declining populations, conservation work remained limited in both states until the 1970s.

In 1970, California listed the Sierra Nevada bighorn and a small population subset of desert bighorns in Southern California, known as the peninsular bighorn, as threatened species. The designation drew the attention of biologists, including Wehausen, who started working to protect the Sierra Nevada bighorn in 1974 as a graduate student.

Three Sierra Nevada bighorns are moved via helicopter in an effort to start a herd unit in a new location, photo by Steve Yeager

After developing a new technique for counting the sheep, Wehausen determined in 1978 that around 250 bighorns remained in the Sierra, living in three distinct herds. All were located in the high country above the town of Independence, on the slopes of Mount Williamson and Mount Baxter.

Armed with this data, Wehausen collaborated with the California Department of Fish and Wildlife (CDFW) and other scientists to draft the first Sierra Nevada bighorn recovery plan in 1984. The plan called for the reintroduction of bighorns into 14 known herds, including several large groups that could be used for translocating sheep to smaller herds.

To begin the recovery process, a couple dozen bighorns from the two herds on Mount Baxter were translocated to three new herd units on Mount Langley, Wheeler Ridge and in Lee Vining Canyon. This was done by catching bighorns with nets and transporting them via helicopter, a process Wehausen says is more humane than one might think.

“We don’t tranquilize them or give them any drugs to move them,” says Wehausen. “We just hobble them with the nets, blindfold them, and then place them into the bags that are flown under a helicopter. Bighorn are so visually orientated that once you place a blindfold over their eyes, they become very docile.”

Using this technique, the recovery program was immediately successful. The Sierra Nevada bighorn population had grown to over 300 by the mid-1980s, spread across six herds.

The success was short-lived, however, as recovery efforts in the Sierra met a couple of formidable new foes moving into the late ’80s—drought and mountain lions.

In 1986, California began a crippling six-year drought that drastically reduced the alpine vegetation the bighorn relied on for food. For reasons somewhat unclear, the drought also corresponded with a dramatic spike in mountain lion populations, one of the bighorn’s few predators.

Between the lack of food and the dramatic increase in predation, Sierra Nevada bighorn populations went into a tailspin for the next decade. By the mid-90s, all previous gains of the recovery program had been lost, and just over 100 bighorns remained in the Sierra.

Rocky Mountain bighorns, the largest bighorn subspecies in Nevada, stop traffic in Lamoille Canyon in the Ruby Mountains, photo by Seth Lightcap

Controversial Conservation in Nevada

Conservation work supporting the desert bighorn in Nevada in the late 1970s and early ’80s followed a similar path to California, but with an interesting twist.

In 1973, the desert bighorn was designated the Nevada state animal, which helped increase support for its recovery. Like its counterpart in California, the Nevada Department of Wildlife (NDOW) began a recovery program in the mid-70s that sought to reestablish bighorn herds in Central Nevada using wild sheep from the few remaining herds in Southern Nevada.

After learning the ropes of sheep translocation, the program succeeded in establishing several new herds of desert bighorns. Only so many bighorns in Southern Nevada could be sustainably relocated, however, so moving into the ’80s, NDOW started to experiment with an alternative restocking strategy.

Taking advantage of healthy bighorn populations, the state began repopulating ranges in Northern Nevada with Rocky Mountain bighorns—as well as a regional lineage of Rocky Mountain bighorns that were erroneously named California bighorns, which were relocated from Canada. The Rocky Mountain bighorns were introduced to the Ruby and East Humboldt ranges near Elko, while California bighorns were introduced to the Sheldon National Wildlife Refuge in northwestern Nevada.

Though it was not well understood at the time, neither of these bighorn subspecies historically lived in Nevada.

Cox started working with bighorns in Nevada in 1993 and was not involved with the collection of wild sheep from Canada, but like the issues that arose from domestic sheep grazing, he is now managing the effects of introducing these non-native bighorns.

“They thought the Ruby Mountains looked like the Rocky Mountains of British Columbia, so they went to Alberta and brought back Rocky Mountain bighorn,” says Cox. “Northwestern Nevada has buttes and plateaus that resemble southern British Columbia, so they got California bighorn from the Okanagan region for that area.

“We realized only after these subspecies were released that the entire Great Basin was all desert bighorn territory. I can’t fault those who made the decision to bring them in, but then again, I can. They should have had the common sense to know there are no boundaries in Nevada; everything is connected.”

The push to introduce Rocky Mountain and California bighorns was heavily influenced by conservation groups led by sportsmen focused on creating more hunting opportunities. Nevada had reopened a bighorn hunting season in 1952, but the tags were extremely limited, so the sportsmen wanted more bighorns in the state any way they could get them.

“Some people think it’s great that the state has three bighorn subspecies,” says Cox. “Scientists obviously question it, but it is what it is, and we’re working with it.”

Despite their foreign heritage, both the Rocky Mountain and California bighorn populations thrived upon introduction to their respective ranges. These successes were matched by further successes relocating desert bighorns into Central Nevada from Southern Nevada. Disease from domestic sheep contact was still an issue, but not enough to erase the gains of relocations.

Many desert bighorn habitats in Southern Nevada were also improved at this time by the creation of man-made water developments called guzzlers. The guzzlers collect water from rain and snow melt in large tanks and provide a more consistent water source for bighorns and other desert wildlife during the dry summer months.

With successful reintroductions of bighorns across the state, Nevada’s population grew substantially in the 1980s and ’90s. By 2001, Nevada was home to an estimated 6,500 bighorns occupying 74 mountain ranges.

Around 20 percent of all Sierra Nevada bighorns are radio-collared, which allows researchers to track their seasonal movements, photo by Steve Yeager

Calling in the Feds in California

While Nevada’s sheep were on the rebound in the 1990s, Sierra Nevada bighorn populations were at their lowest point in known history due to mountain lion predation.

The CDFW’s bighorn recovery plan drafted in 1984 specified a protocol for removing lions that were targeting bighorn herds, which resulted in the killing of several offending lions by the late ’80s. But just as lion predation was peaking, the state passed the California Wildlife Protection Act of 1990, which eliminated the CDFW’s ability to kill lions. The newly protected animals had to be trapped and moved, a process that was both difficult and ineffective, as the relocated lions would often return to their former territories.

Wehausen and fellow Sierra bighorn conservationists were taken aback by this legal development.

“After two decades of successful conservation work, the California Wildlife Protection Act was about to upend all our work,” says Wehausen. “Suddenly, our only solution was to try and get federal law to supersede this state law.”

That’s exactly what they did. In 1999, Wehausen and the CDFW successfully petitioned the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to grant emergency endangered status. Once the Sierra Nevada bighorn was officially listed as a federally endangered species, lethal control of mountain lions could resume. To respect the Wildlife Protection Act, the CDFW also began placing radio collars on lions near bighorn ranges and monitoring their movements to be as selective as possible in their removal.

“The federal listing saved the species, but we really paid the price,” says Wehausen. “We needed to be doing lion control well before we got the listing. The current status of Sierra bighorn would be very different had that happened.”

The added protections to start the twenty-first century were successful in turning the tables for Sierra bighorns, as the populations quickly began to rebound. By 2004 the estimated number of Sierra bighorn was back up to nearly 350, more than double the low point of 100 sheep in 1995.

Sierra Nevada bighorns forage for food in a deep Sierra spring snowpack, photo by Steve Yeager

Success and Shout-Outs in Nevada

Building off successes in the 1980s and ’90s, bighorn numbers in Nevada have continued to improve the past two decades. When there are setbacks in localized herds, domestic sheep are usually the cause, says Cox.

“Disease from domestic sheep is still something that we are struggling with. We have die-offs every few years and we’ll lose 100 adults in four or five months to pneumonia,” says Cox. “We have been extending our olive branch to the wool growers and educating them about the science of the trigger pathogens, but it’s a real challenge. Domestic sheep are asymptomatic to these pathogens, so there is no effort to develop a vaccine that could help reduce the spread.”

The unexpected die-offs have taken their toll on some herds, but overall, populations have grown so much in recent years that Nevada has been able to offer some bighorns to Texas and Oregon to help increase numbers in those states. Bighorn hunting tags have also increased dramatically, a boon to Nevada’s conservation groups that Cox feels is well-deserved.

“I have to give a huge shout-out to the bighorn conservation groups in Nevada,” says Cox. “They are mostly hunters, but they appreciate wildlife whether they could hunt or not, and they have been right next to us this entire time helping recovery efforts.”

Cox also notes that Nevada’s bighorn management plans continue to support the growth of the two non-native bighorn subspecies.

“We’ve accepted the fact that we have three species and we’re not afraid of hybridization,” says Cox. “We are moving desert bighorn closer and closer to the Rocky Mountain and California bighorn, and we’ve already seen hybridization.”

Today, there are an estimated 12,000 bighorns in 100 herds throughout Nevada, including 9,500 desert bighorns, 2,000 California bighorns and 300 Rocky Mountain bighorns, says Cox.

A young Sierra Nevada bighorn ram eyes an intruder, photo by Steve Yeager

A Roller Coaster in the Sierra

Sierra Nevada bighorn populations were on the rise after their federal designation as an endangered species in 2000. With ample food and lion predation under watch, this success continued unchecked for the next 15 years. By 2013 the numbers had rebounded so well that CDFW could begin translocating bighorns again.

Following an updated recovery plan created in 2007, Sierra Nevada bighorns were reintroduced to another six areas, bringing the total number of herds in the Sierra to 14, including a couple that developed from natural range expansions.

Tom Stephenson, CDFW’s Sierra Nevada Bighorn Sheep Recovery Program leader, began working with Sierra bighorns in 2001 and played a major role in the successful translocations. He attributes the success to the protections afforded by the federal listing as an endangered species, as well as the designation of wilderness areas that encompass large portions of Sierra bighorn habitat.

“One thing that is unique with Sierra bighorn is that the native habitat is still all intact,” says Stephenson. “For most endangered species, that’s what makes their situation so bleak: We’ve lost their habitat. We are really fortunate that the vast majority of the Sierra bighorn’s habitat is protected wilderness.”

By 2016 the Sierra Nevada bighorn population had climbed to nearly 700, and there was talk of changing their status from “endangered” to “threatened.” Conservationists were thankful it was just talk because the winter of 2016-17 was one of the biggest snow years on record, which dealt a rude blow to the bighorn.

Many died of starvation, unable to find food in the deep snowpack. Several more died in avalanches and nearly 30 were killed by mountain lions that targeted a herd on Mount Langley that had been trapped by snow in a small pocket of dry terrain. In one season, the Sierra bighorn population got knocked down to below 600.

“As painful as it was to see a decline in the population when things were going so well, I’m glad it happened when they were still federally listed, instead of shortly after being delisted,” says Stephenson. “The recent declines have also given us a much better understanding of bighorn population dynamics and all the factors that allow herds to persist or not persist. Moving forward, we really need to make sure the Sierra bighorn population is as robust and widely distributed as we can make it, because anomalous events like this are going to happen that will drastically affect our ability to recover this animal.”

Sierra Nevada bighorn populations have remained relatively stagnant since the big crash in 2017, with current totals estimated around 600 animals spread across 14 herds.

Sierra Nevada bighorns are most easily seen in the winter when they move down to lower elevations, photo by Steve Yeager

New Bighorn Developments

Much to Wehausen’s chagrin, mountain lions remain one of the Sierra bighorn’s biggest threats.

“There were some recent changes to the (CDFW’s) fish and game code that dictates how we manage mountain lions in the state,” Stephenson explains. “We’re back to trying to implement non-lethal measures, before using lethal measures. The new policy doesn’t preclude us from using lethal measures, but the first option is to try and relocate lions. We are still evaluating how well that can work.”

The new policy has had mixed success thus far. In the last year, two lions that were targeting Sierra bighorns were captured and moved. One of those relocations was successful, with the lion remaining in the new area. The other lion walked a couple hundred miles back to its former home.

“It’s such a strange situation,” says Wehausen. “The new policy goes against what the CDFW had already determined to be the best solution. They had tried to move lions in the past, but had stopped doing it because of problems. But we are redoing that experiment again. We’ll see how it works out this time.”

Though Nevada does lose bighorns to predation, lion management is not a hot topic in the state. NDOW is allowed to use lethal measures, and does, if a lion is found to be preying on a herd.

The latest bighorn news in Nevada is the reintroduction of the species to the Pyramid Lake Paiute First Nation land.

“The mountains surrounding Pyramid Lake were historic bighorn habitat until they were extirpated from the area in 1910,” says Cox. “We reintroduced 22 California bighorn to the Lake Range on the east side of the lake in 2020 and another 16 this year.”

According to initial reports from the Pyramid Lake Paiute Tribe’s biologist, the reintroduced bighorns are doing well, with many lambs born the first year.

The current distribution of bighorn sheep in California, courtesy California Department of Fish & Wildlife

Committed to Conservation

Differences in strategies aside, what makes the status of bighorn sheep in California and Nevada so inspiring among threatened and endangered species of the world is that both states have been successful in assembling the most important pieces of the conservation puzzle—protected habitats and public support. Now it’s just a matter of being patient and recognizing that the balance of nature will never be completely in our control, says Stephenson.

“When you do this kind of work, whether as an individual or an agency, you have to be in it for the long term,” he says. “You are working on an ecological timescale that is really decades, not just years. No matter our efforts, we will have good years and we will have bad years because there are so many things that fluctuate in the environment that affect the persistence of this species that are beyond our control.”

Conservationists can also take comfort in the fact that there will likely never be a threat to build shopping malls or subdivisions in bighorn country, a reality that Muir was grateful for.

“Man is the most dangerous enemy of all, but even from him our brave mountain-dweller has little to fear in the remote solitudes of the High Sierra,” said Muir. “The golden plains were lately thronged with bands of elk and antelope, but, being fertile and accessible, they were required for human pastures. … But it will be long before man will care to take the highland castles of the sheep.

“And when we consider how rapidly entire species of noble animals, such as the elk, moose and buffalo, are being pushed to the very verge of extinction, all lovers of wildness will rejoice with me in the rocky security of wild sheep, the bravest of all Sierra mountaineers.”

Seth Lightcap is a writer and avid High Sierra explorer from Olympic Valley who has always been inspired by the bighorn’s fearless footwork and tenacious talent for climbing mountains.

Finding Bighorns

Sierra Nevada bighorns are tricky to spot, but the best chance is in the winter months when they come down to lower elevations. Pine Creek Canyon outside of Bishop is one area where they are frequently spotted between December and March. Nevada’s bighorns are much easier to find. They are often spotted—and photographed—near Walker Lake on Highway 95, as well as Lamoille Canyon in the Ruby Mountains.

How to Help

Those looking to get involved with Sierra Bighorn conservation can become a member of the Sierra Nevada Bighorn Foundation. The nonprofit organization is based in Bishop and helps support the work of the California Department of Fish and Wildlife. Learn more about the foundation at www.sierrabighorn.org. Nevada is home to several bighorn conservation groups, including Nevada Bighorns Unlimited and the Wild Sheep Foundation. Learn more about the foundations at nevadabighornsunlimited.org and wildsheepfoundation.org.

No Comments