09 Aug The Land of Fire and Snow

Lassen Volcanic National Park celebrates its 100th birthday this year—but the area has been a geologic treasure for millennia

One hundred fifty miles north of Lake Tahoe lies a scenic alpine landscape that is being tortured from below. Pools of scalding mud gurgle and churn in protest. Steam hisses out of tears in the earth. On rare occasions, entire mountaintops, pent-up with thousands of years of pressure, blast off with explosive force.

This is the story of Lassen Volcanic National Park.

“With all the geothermal activity there, it’s just a magical land,” says Mark McLaughlin, a Tahoe weather historian and geographer.

Situated at the crossroads of three major geographical provinces—the Sierra Nevada to the south, the Cascade Range to the north and the Great Basin to the east—this 106,092-acre chunk of Northern California holds its own among the nation’s great national parks. Yet it flies under the radar, drawing a fraction of the visitors as its more famous neighbor to the south, Yosemite.

Park officials expect record numbers of visitors in 2016, however, as Lassen, which became the nation’s 15th national park on August 9, 1916, celebrates its centennial along with the U.S. National Park Service.

“What’s really cool is that, because it’s our centennial, a lot of people are finding out about the park,” says Karen Haner, Lassen’s chief of interpretation and education. “Amazingly enough, a lot of folks in our surrounding communities may know about it, but they don’t come to visit. They may think about it now.”

Those who do visit Lassen Volcanic National Park—which hosted 468,092 visitors in 2015, compared to 4,294,381 in Yosemite—are treated to an otherworldly land of natural splendor.

In addition to the mud-bubbling, ground-steaming evidence of its fiery underbelly, the park contains all four types of volcanoes in the world, the largest snow totals in the state, prize fishing in its gin-clear waters, and a rich diversity of animal and plant life.

There are more than 150 miles of hiking trails inside the park, including the Pacific Crest Trail cutting through the heart of its wilderness, and a 30-mile scenic byway that climbs to an elevation of 8,500 feet. While the road closes from winter through early summer, the park remains open year-round and offers ample terrain and solitude for backcountry skiers and snowboarders.

“I think we have some of the best backcountry skiing around,” says Todd Jesse, a park guide. “Unlike places like Tahoe and Shasta, you don’t ever really have to search for a parking spot here. It’s kind of a hidden little gem that not many people make their way out to.”

Bumpass Hell is the largest hydrothermal area in Lassen Volcanic National Park, photo courtesy NPS

Blasting onto the Map

Despite efforts over the previous decade, it took a series of explosive events before the National Park Service adopted Lassen.

The park’s dominant feature, 10,457-foot Lassen Peak, awoke from a 27,000-year dormancy with a well-documented flurry of eruptions between 1914 and 1917. It began May 30, 1914, when the first of more than 180 steam explosions rattled the mountain and carved a 1,000-foot-wide crater at the summit. But, the blasts were merely a precursor to bigger, more destructive events to come.

Those events were set in motion on May 14, 1915. In the darkness of night, incandescent blocks of lava tumbling down the mountain’s steep western flank could be seen from as far as 20 miles away. By the next morning a dome of growing lava had filled the newly formed crater.

Four days later, around midnight on May 19, a large explosion shattered the lava dome and spewed glowing chunks of hot lava onto the deeply snow-covered mountain (the 1914–15 winter was the first recorded El Niño in the United States, and the upper portion of Lassen Peak was buried under more than 30 feet of snow).

The blast triggered a half-mile-wide avalanche of snow and rock that ripped four miles down the north face of the volcano. As the thermally heated rocks broke apart, the snow melted, creating a giant mudflow known as a lahar, which snapped large trees like toothpicks before spilling over a low ridge and flowing another seven miles down a creek. Large volumes of muddy water continued downslope, flooding the lower Hat Creek Valley and chasing residents in the Old Station area from their ranch homes, many of which were destroyed in the flood. Miraculously, all the homesteaders escaped with their lives.

As destructive as the eruption was, Lassen Peak had yet to unleash its full fury.

Following two quiet days, the volcano erupted again the afternoon of May 22. That blast, which formed the larger of the two craters present today, sent debris more than 30,000 feet into the air. The plume could be seen from as far away as Eureka, California, 150 miles to the west, while fine ash rained down as far away as Elko, Nevada, 280 miles to the east.

In the immediate vicinity, a high-speed torrent of pumice, hot ash, rock fragments and gas—known as a pyroclastic flow—tore down the north side of the volcano, devastating a three-square-mile swath. As the pyroclastic flow melted the snow in its path, it transformed into a highly fluid lahar that swept down the same path as the May 19 lahar and rushed 15 miles down creek, again flooding the Hat Creek Valley. The eruption created smaller mudflows down all sides of Lassen Peak and deposited a layer of pumice and ash 25 miles to the northeast.

Steam eruptions continued for another two years, including a particularly large event in May 1917 that created the smaller of the two craters still seen on Lassen’s summit.

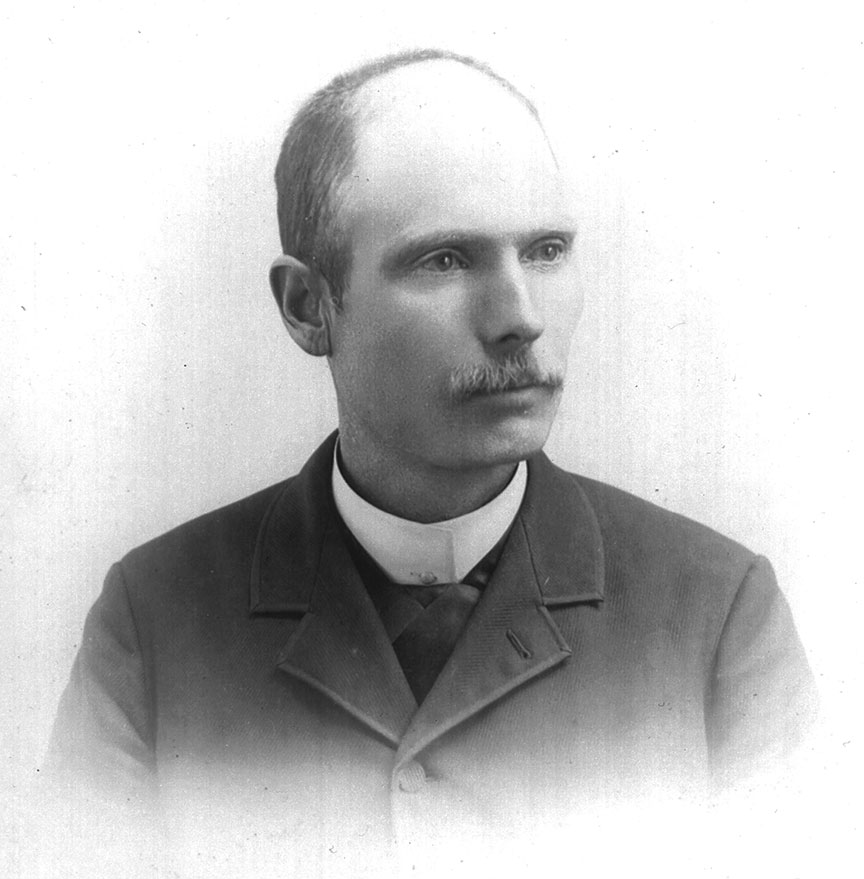

Although many photographs exist from this tumultuous time, Benjamin Franklin Loomis, a businessman and amateur photographer who owned property to the northwest of Lassen Peak, left the best-documented photographic records. He published a book of the images and, as a staunch supporter for Lassen Volcanic National Park’s formation in 1916, later donated his photographs, 40 acres of land and a museum he and his wife built.

The Loomis Museum still exists, while the land Loomis donated around Manzanita Lake is among the more commonly visited locations in the park.

Steaming crater on Lassen Peak summit, photo by B.F. Loomis, October 20, 1914

Explosive Origins

The eruptions of 1915 were tame compared to the area’s more violent past.

The Lassen region has been volcanically active for roughly three million years, according to research by the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS). Lassen Peak and its neighboring volcanos are the most recently active portions of what scientists call the Lassen volcanic center, which began erupting around 600,000 years ago.

Multiple eruptions between about 400,000 and 600,000 years ago—the largest of which was 50 times larger than the 1980 eruption of Washington’s Mount St. Helens—built a massive volcano called Brokeoff Volcano, or Mount Tehama, which towered more than 11,000 feet and had a base more than 11 miles wide.

The volcano, located just inside the southwest entrance of the park, later became inactive and was mostly eroded away and scooped out by glaciers. The southern and western rim of this ancient volcano now make up Brokeoff Mountain, Mount Diller, Mount Conard and Diamond Peak, all of which provide steep, open slopes ideal for backcountry skiing.

Lassen Peak, which began as a vent on the northern flank of Mount Tehama, formed as the result of eruptions about 27,000 years ago. The Chaos Crags just north of Lassen Peak formed about 1,100 years ago, while Cinder Cone in the northeastern corner of the park erupted around 350 years ago, according to the research of Michael Clynne, a geologist with USGS Volcano Science Center.

The Lassen volcanic center remains active and will erupt again, Clynne says. But there’s no telling when.

“We’re monitoring it, and we will expect to see seismicity and ground surface deformation before it erupts. So there will be some warning signs,” he says.

The largest volcanic eruption of California’s relatively recent past occurred at the Long Valley Caldera near Mammoth Mountain, Clynne adds. That volcano—which is categorized as a supervolcano, the largest kind on Earth—erupted about 680,000 years ago and affected the entire Western United States.

“The biggest one at Lassen was only about a tenth the size of Long Valley,” he says. “But it was still a big eruption and would cause a lot of problems today.”

Hiking up Cinder Cone, photo by Martin Gollery

Modern History

Before being designated as a national park in 1916, the Lassen area was a summer meeting point for four different American Indian groups, the Atsugewi, Yani, Yahi and Maidu. It later became a pathway for European emigrants traveling west.

The name Lassen Peak stuck after rancher Peter Lassen, a Danish-born immigrant, traveled to California in 1840 and became the first American to summit the peak.

Lassen established the Lassen Cutoff of the California Trail, which crossed the ominous Black Rock Desert, claiming it was a better alternative than the more established Truckee and Carson routes. Lassen’s route was actually about 200 miles longer and no less dangerous to travel.

The remote volcanic landscape around Lassen Peak remained largely uninhabited throughout the California Gold Rush. Word of its hydrothermal nature slowly spread, however, and in 1865 the first reference to its geology was documented in the Whitney Survey Memoir. By 1905 the Lassen National Forest was established, and two years later President Theodore Roosevelt signed a proclamation establishing Cinder Cone and Lassen Peak national monuments.

Although attempts to designate the area as a national park began as early as 1906, it wasn’t until the 1915 eruptions that the concept of Lassen Volcanic National Park gained footing. A little over a year later, on August 9, 1916, the park was officially established.

The original boundaries protected 82,880 acres and included Lassen Peak, Cinder Cone and Bumpass Hell, the largest hydrothermal area in the park. Parcels of land were gradually added all the way up to the acquisition of Spencer Meadows in 2012, bringing the park to its current size of 106,372 acres.

Capitalizing on the abundance of terrain and snow, the park opened a small ski resort just inside the southwest entrance in the 1920s that remained a popular attraction through the middle of the century. A portable rope tow and warming hut were constructed at the resort in 1935, a two-person chairlift—called Bumpass Heaven—was installed in 1956, and an A-frame ski chalet was built in 1964, Haner says. The Mt. Lassen Ski Club held ski tournaments and jumping competitions in the 1930s, and Olympic skiers even trained on occasion at the site, adds Haner, who learned to ski on the resort’s bunny slope.

The ski area operated until 1993, when it was shut down as a result of competition from Mount Shasta Ski Park, as well as the National Park Service’s initiative to move away from developments. The old chairlift foundations were removed in 1999, Haner says, and in 2005 the ski chalet was deconstructed to make way for a new building, the Kohm Yah-mah-nee Visitor Center.

Few remnants of the old ski resort remain. In fact, with a couple of modern exceptions, the park is nearly as primitive as it was at its inception.

Large groups of skiers in Lassen Park, 1936, photo by Jervie Henry Eastman, courtesy Department of Special Collections, General

Library, University of California, Davis

Lassen at 100

Today, summer visitors enjoy camping, fishing and hiking on the many trails that access the park’s features, from the most remote pockets to short treks off the scenic byway.

The park houses eight campgrounds and prime fishing for rainbow, brown and brook trout. Jesse, the park guide, says Manzanita, Butte and Horseshoe lakes offer the best angling opportunities, as does Hat Creek, which is regarded as one of the best fly fishing waters in the state.

The most commonly hiked trails are the Lassen Peak Trail, which climbs 2,000 feet in 2.5 miles to the summit of Lassen Peak, the 1.5-mile Bumpass Hell Trail and the Kings Creek Falls Trail. The Sulphur Works hydrothermal area requires no walk at all, as its boiling puddles are located right off the main road.

Bumpass Hell—named after an early settler who severely burned his leg after slipping into a boiling pool—marks the principal area of discharge from the Lassen hydrothermal system, which is readily seen in the form of its gurgling mud pools, steaming fumaroles and unusual, multi-colored soils. The steam jetting from Big Boiler, the largest fumarole in the park, can reach temperatures over 320 degrees, making it one of the hottest fumaroles in the world.

Due to the massive snow totals, the main road through the park is typically closed through early summer. Camping is available at the southwest entrance, however, with the visitor center nearby and easy access to backcountry skiing and snowboarding. Snowshoeing and sledding are also popular.

Whatever the activity, beauty and solitude are not hard to find among this picturesque landscape built on a tormented past.

Sylas Wright is the new editor of Tahoe Quarterly. He recently enjoyed a weekend camping trip in the park.

Lassen Peak is pictured from the top of Brokeoff Mountain, photo courtesy NPS

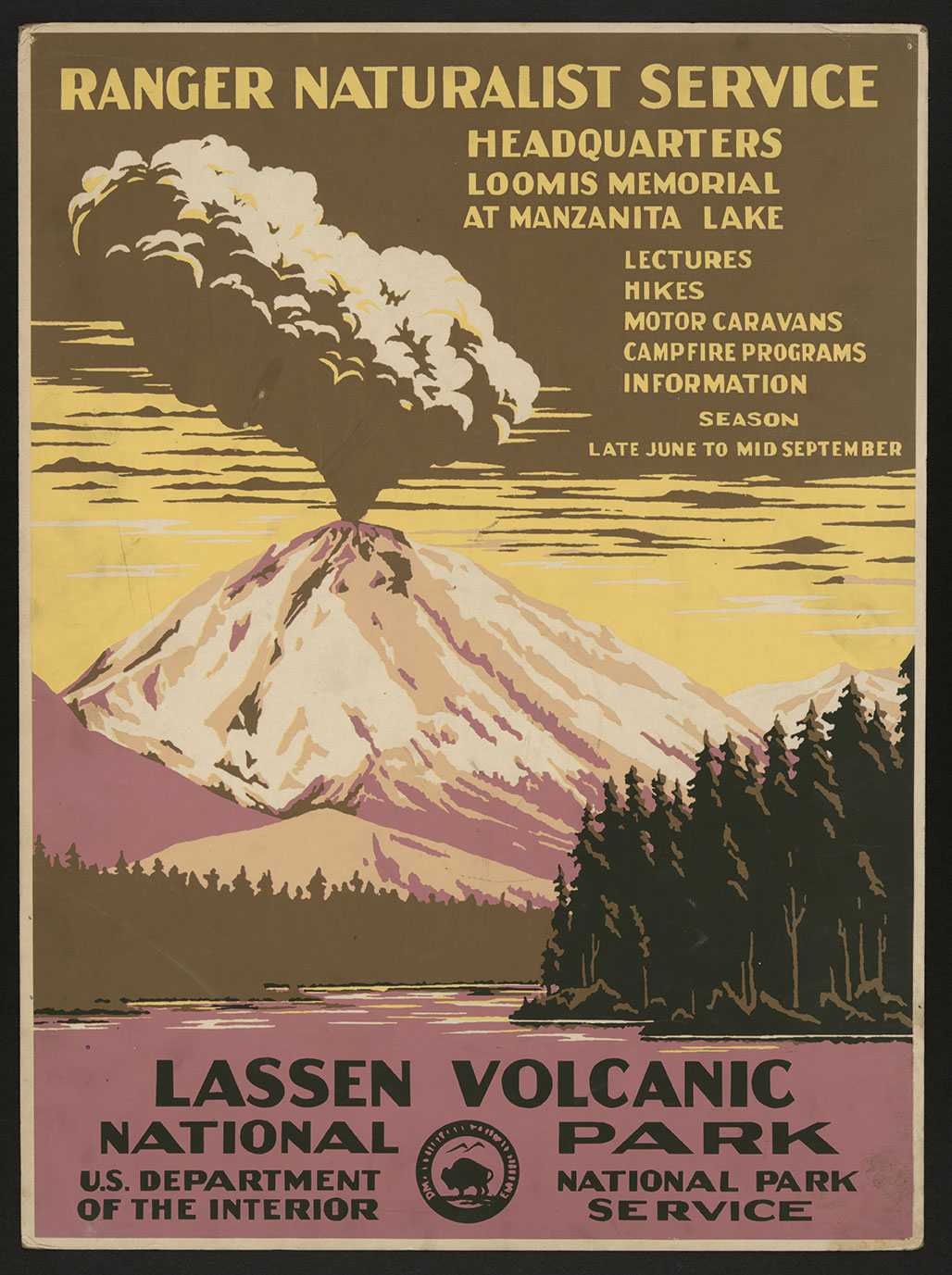

Lassen Volcanic National Park, Ranger Naturalist Service poster from 1938,

courtesy Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division

Benjamin Franklin Loomis, photo courtesy NPS

Buried by Snow, Battered by Sun, Truckee Firm Designed Visitor Center to Withstand the Elements

Written by Kyle Magin

The Kohm Yah-mah-nee Visitor Center is located just inside the southwest entrance of the park, photo courtesy NPS

Robert Heck first saw Lassen Volcanic National Park as an 8-year-old growing up in Northern California. Throughout his youth and adulthood, the Truckee-based architect, a principal at Ward-Young Architecture and Planning, spent many days fly-fishing Hat Creek and Manzanita Lake, navigating some of the best angling in the Golden State inside the park’s boundaries.

As an adult, he earned a chance to leave his mark on the park when he led Ward-Young and a team of consultants into a mammoth undertaking: designing and building the Kohm Yah-mah-nee (which means ‘Snowy Mountain’ in Maidu) Visitor Center near the park’s southwestern entrance, just off of Highway 89. For many visitors, it’s a jumping-off point, a good place to gather beta on Lassen’s camping and adventures, learn about the park’s natural history, and check-in for backcountry permits before exploring one of Northern California’s natural wonders.

“That side of the park needed the visitor’s center. It needed something to welcome people in,” Heck says. “It was fun to be a part of the project.”

After several years of design efforts that failed to meet construction cost requirements, the National Park Service decided to change direction and sought a design-build approach to the project. In 2006, Ward-Young partnered with Slayden Construction out of Stayton, Oregon, to advance a design-build bid for the facility. The two companies worked together previously on the 1998 Mt. Judah Lodge project at Sugar Bowl and together entered a successful bid to build Kohm Yah-mah-nee in 2006. Completion of design and construction took up much of the next two years, with a soft opening for the center in the summer of 2008.

Ward-Young improved upon the proposed design in order to more accurately reflect and respond to the legacy of national park architecture and the extreme environment at Lassen. The building had to withstand 300 pounds of snow load per square foot, and up to 600 on the eaves owing to Lassen’s high elevation. It’s not uncommon to see pictures from heavy snow years such as 2010–11 where Kohm Yah-mah-nee is nearly completely buried, only the outline of its eaves visible. The building houses dining concessions, park information, 24-hour restrooms for a nearby campsite, an indoor theater, an outdoor amphitheater and an exhibit on the park’s many geologic features.

“The eaves on that building are up to 12 feet high, and I’ve seen snow on that roof at least 12 feet deep,” Heck says. “Despite the structural challenges, one of our goals was to provide substantial overhangs at the roof to help protect the walls and entries.”

During construction, Heck sometimes visited the site every other week, hauling a camper up to the park’s headquarters in nearby Mineral, California—a task the outdoor enthusiast welcomed, he says.

Fashioned out of heavy timbers and columns, stained concrete and stone, the visitor’s center immediately opens upon entry to a large window wall with panoramic views to the park’s southern peaks—Mt. Diller among them. A LEED-Platinum certification—the highest awarded by the U.S. Green Building Council—was earned in 2009 by an unrelenting focus on behalf of Ward-Young, Slayden, the Rocky Mountain Institute (a LEED consulting firm that worked with the design team on the project) and the Park Service. Part of the certification came from the team’s ability to source materials locally—seasoned log columns, found mainly in the Northern Rockies, were sourced from Greenville, California, just south of Lassen, Heck says. Native stone came from quarries downslope of the park to the west. A photovoltaic array was situated atop a building at park headquarters in the comparatively less-snowy Mineral, California, which helped to offset energy use at Kohm Yah-mah-nee, while lights throughout the center automatically dim throughout the day in response to increasing daylight.

Heck’s favorite parts of the building are the view that opens up through the entry, and the way the spaces and structure flow from the center of the building. Heck treasured the experience of building in a park he’s so familiar with, he says.

“All in all, the project was a great success.”

No Comments