27 Sep Yosemite Valley: The Switzerland That Never Was

From early-day aspirations to replicate the ski resorts of the Alps to its modern-day status as a forgotten world of snow-starved extreme skiing, Yosemite Valley boasts a storied history of winter sports

Taylor Carlton hovers through a rock garden riding a gully across from El Capitan, photo by Seth Lightcap

Ecstasy or terror? The appropriate emotion is a tough call.

Feelings are not a priority at the moment, though. Our eyes have full control of our brains as we stare in rapture at our surroundings.

The four of us, all backcountry snowboarders from Lake Tahoe, are looking out from a cliff-top perch on the south rim of Yosemite Valley. Our gaze is locked on the towering face of El Capitan.

We have all seen the 4,000-foot-tall granite monolith many times, but we have never seen El Capitan look like this before. On this moody morning in March 2019, the rim of the massive stone shield and the entire valley below is blanketed in fresh snow. From our vantage, with nothing but a mile of fresh air between us and El Capitan, the winter wonderland that falls away below our boots is an otherworldly sight.

We drove down to Yosemite National Park the night before on a mission to snowboard down a steep gully across from El Capitan that drops from the south rim to the valley floor. It is a backcountry descent we have dreamed about for years with only fleeting hopes of ever pulling off because of its low elevation.

The gully starts at 7,000 feet and drops through a series of cliff bands and talus fields down to about 4,200 feet. Most recent winters, only the top of the gully holds snow. But this winter, for the first time in years, a series of colder-than-usual storms have caked Yosemite in snow right down to the base of the valley.

Strapping in to start our descent, we’re giddy and nervous. The snow looks mostly deep enough. You can’t see many rocks, anyway. But surely, sharks are lurking everywhere. Avalanche danger is also a concern as the fresh snow is starting to warm up.

One at a time we drop into the gully, making tentative first turns to test the snow stability. The snow stays put, easing our fears, and soon we are leapfrogging down the line, watching each other rip turns among gigantic rock towers and house-sized boulders.

A couple hundred vertical feet short of the valley floor, the snow-to-rock ratio gets sketchy, so we unstrap and start thrashing through dense forest down to the road. We are elated to safely reach the road. Smiles nearly as big as El Capitan plaster our faces as a wave of deep satisfaction washes over us.

While all of us have ridden steeper, deeper and more challenging descents, shredding this gully is a historic moment in all of our snowboarding careers. Why? Because the line is in the holy land, Yosemite Valley-which to many worshipping Sierra disciples is the most sacred, beautiful and life-affirming valley in the entire range.

Jason Torlano pops out of a pow turn on the first descent of the Bushido Gully in March 2021, photo by Eric Rasmussen

If Only It Would Snow … Again

Everybody knows Yosemite Valley as the premier attraction in Yosemite National Park, and one of the most spectacular rock climbing, hiking and overall natural sightseeing destinations in the world. But a ski destination? Not so much.

Carved by glaciers to an elevation of 4,000 feet, Yosemite Valley is now too low to be a consistent ski destination. In recent years you’d be lucky to see more than 4 inches of snow on the valley floor. And you’d better look quickly, as what little snow does fall usually melts within a day, if not hours.

But at the turn of the nineteenth century, the valley still got lots of snow. Even into the 1920s it wasn’t unheard of to see a 4-foot snowpack in the valley midwinter. Living, working and playing in such deep snow on the valley floor convinced the park’s first developers that Yosemite would be a radical ski destination. And it would have been. But then it stopped snowing as much.

Dreams of making Yosemite a ski resort faded as climate change took hold. But as we’ve learned, warmer temperatures and a shrinking snowpack are a trend, not a mandate of Mother Nature. Every few winters over the past 50 years, a series of cold and powerful storms have pummeled Yosemite like the good old days. And when this happens, Yosemite Valley transforms back into one of the most epic ski destinations on the planet, and a proving ground for backcountry skiers unlike any other location in the Sierra.

What makes Yosemite Valley such a special zone for skiing are the same reasons it’s so perfect for rock climbing. The walls are really steep, yet also fairly featured with rock towers and gullies that break up the sheer expanses of granite. It’s these gullies between the cliffs that collect the snow and hold the ski lines.

Some of the gullies fill in to become continuous runs from rim to valley. Others require rappels and rope work to navigate regardless of snow coverage. All the lines are exposed to every backcountry skiing danger imaginable: avalanches, icefall, rockfall and cliffs. But when the snow stacks up, and the conditions are just right, the ski routes within these hidden corridors are what backcountry ski dreams are made of—smooth and breathtaking passages through seemingly impenetrable mountain faces.

Gotta Be There

No skier past or present knows the thrill of skiing in Yosemite Valley better than Jason Torlano.

Torlano moved to Yosemite at age 5 and grew up dreaming about skiing the wild chutes that cascade down the valley’s walls. Now 46, he is without a doubt Yosemite’s most accomplished and daring local skier, with a couple dozen first ski descents in the valley to his name, including lines on Clouds Rest, Half Dome, Mount Watkins and several different high points on the south rim.

For Torlano, there is no other place on earth he’d rather ski.

“I love Yosemite so much. Skiing here is always the most amazing experience for me because I love it so much,” Torlano says about his home turf. “It’s just so beautiful and I love the challenge of finding new lines.”

Torlano now lives with his wife and two kids in the small community of Sugar Pine, just outside the park’s south entrance. He is the first one to admit, living close to the park gives him a serious advantage in skiing there.

“Snow in the valley never sticks around long enough,” Torlano laments. “You have to watch the storm cycles and be prepared to go right when the storm cycle is done.

“And that’s the crux—just being there at the right time. More people might be skiing this stuff if they lived right there.”

If former pro snowboarder Jim Zellers lived in Yosemite, you can bet he would be laying tracks into the valley any chance he could. Zellers, who lives in Truckee, was the first skier or snowboarder to ride off the summit of Half Dome without a safety line. He knows the struggle of nailing snow conditions in the valley firsthand. But for him, the struggle is a blessing.

“You can get a decent snow report from just about anywhere you want to ski these days, but not Yosemite,” says Zellers.

And that’s what he loves about it.

“There is never any beta to be had on snow conditions in Yosemite because so few people ski there,” says Zellers. “You’ve got to figure out the mysteries of Yosemite’s funky snowpack on your own. I love that part about riding there. We don’t get many opportunities for unknown adventures like that anymore.”

Living in or near the park and learning the ebb and flow of the local snow has always been the secret to unlocking the finest skiing in the valley. The history of skiing in Yosemite began with the first settlers and park developers who lived in the valley year-round.

First Tracks and Olympic Dreams

The first ski tracks in Yosemite were laid down by pioneer settlers who overwintered in Yosemite Valley in the 1860s. They used wooden longboard skis to travel around the valley midwinter. The longboard skis had been introduced to the Sierra in the 1850s by Norwegian miners.

Yosemite became a national park in 1890. Park status increased summer tourism, but few visited the park in the winter until 1907, when a railroad line was completed to the nearby town of El Portal. The railway opened the door for ski tourism in the valley, as people could now come to the park on day trips to play in the snow and schuss around on skis.

By the late 1920s, Yosemite’s ski tourism was starting to ramp up. There was now a ski hill on a small moraine and guests could rent skis and take lessons at the park’s lodges. All the lodging in the park was operated by the park’s original concessionaire, the Yosemite Park & Curry Company. The president of the Curry Company was a man named Don Tressider, who along with his wife, Mary Curry Tressider, were Yosemite’s first avid skiers. Don and Mary loved to explore the park on skis and felt the new sport should play a major role in the park’s future.

The trajectory of Yosemite’s development took another momentous leap in 1928 when the Tressiders attended the second Winter Olympic Games in St. Moritz, Switzerland. The two were blown away by the competitive festivities of the Games and the world-class ski resort infrastructure of St. Moritz. They returned home more determined than ever to see out their dream of turning Yosemite Valley into the most celebrated ski destination in California. Their outspoken goal was to make Yosemite the “Switzerland of the West,” complete with cable cars to the valley rim and a network of ski huts.

That same year, the International Olympic Committee (IOC) chose the United States as the host of the 1932 Winter Games. The exact location would be selected the following year in 1929. The Curry Company dove headfirst into trying to bring the Olympics to Yosemite Valley.

Their first moves were to create the Yosemite Ski School, which was the first ski school in California, and construct a massive ice rink plus a small ski jump on the valley floor. They hoped these new facilities, and their well-established lodges, including the luxurious and just recently opened Ahwahnee Hotel, would be enough to win Yosemite the bid. Lake Tahoe and Lake Placid, New York, were the other two contending locations for the Olympics that year.

But it wasn’t meant to be. Yosemite beat Lake Tahoe as the top California choice, but at the IOC meeting in Switzerland, board members decidedly awarded the Games to Lake Placid. The IOC didn’t think the Curry Company had enough experience staging winter sports competitions. Lake Placid had successfully hosted many winter carnivals and had the financial backing of the state of New York to help fund construction of new facilities.

Built at Yosemite’s Badger Pass in 1935, the ‘Up-ski’ was a cable-drawn toboggan lift that carried eight skiers and was the first mechanical ski lift in the West, photo courtesy Yosemite Hospitality

Looking to Higher Ground

Undeterred by losing the Olympic bid, the Curry Company kept its focus on transforming Yosemite into a ski resort on par with major European resorts.

The first challenge in this quest was to find a new place to ski. Snowfall on the valley floor was already starting to be inconsistent and skiers had outgrown the challenge of their 50-foot-high ski hill. The obvious solution was to somehow open ski access to longer and higher-elevation slopes on the valley’s rim.

The Yosemite Valley is 3,000 to 4,000 feet deep, so the rim varies in elevation from 7,000 feet to well over 8,000. At this elevation, which is the height of most Lake Tahoe ski resorts, the snow was still plentiful every winter.

In the summer of 1929, the Curry Company made its first forays into developing these slopes by building a ski cabin on the north side of the valley in the Snow Creek drainage. Nestled in the trees 3,000 feet above the valley floor, the Snow Creek Cabin offered direct access to the slopes of Mount Watkins and was a launching point for cross-country ski tours to Tuolumne Meadows and beyond.

Two-day and six-day tours to the cabin were offered using pack horses to carry guests’ skis and equipment up the 7 miles of switchbacks. The Curry Company also arranged to open the Tuolumne Meadows ranger cabins for public winter use, allowing adventurous skiers the opportunity to tour hut-to-hut from Snow Creek to Tioga Pass and back.

Mary Tressider fell in love with skiing the pristine backcountry slopes above the Snow Creek cabin, and was said to have spent over 100 winter nights there in the 1930s. Few skiers of the day were as tough or skilled as Mary, however, and the ski cabin was met with only lukewarm interest from the general public.

Meanwhile, on the south side of the valley, Don Tressider was campaigning to seriously step up Yosemite’s resort infrastructure by installing a cable car from the valley floor to the top of Glacier Point. The tramway would open access to the steep slopes of Sentinel Dome, as well as miles of rolling ski terrain on the south rim.

Dreaming big, Tressider also hoped to install a cable car line to the new Snow Creek Cabin, and potentially a third tramway to Tenaya Lake. With such a network of mechanical lifts, Yosemite would be well on its way toward Tressider’s Swiss dreams. But in a move that would foretell the future of ski resort development in Yosemite, the park’s advisory board roundly rejected all his cable car proposals. The National Park Service was committed to preserving the natural beauty of Yosemite Valley’s magnificent walls.

A bustling day at Badger Pass’ Tyrolean Haus ski lodge in 1937, photo courtesy Yosemite Hospitality

Small and Mighty Badger Pass

Tressider’s pursuit of colder, snowier slopes on the south rim got a major assist in the fall of 1932 with the completion of the Wawona Tunnel. The tunnel, carved through nearly a mile of granite bedrock, connected paved roads on the south rim directly to the valley floor.

The Wawona Tunnel and the new Highway 40 was the Curry Company’s gateway to escaping the valley’s variable snowfall and to establish a legitimate ski resort in the park. By 1935 they had established Badger Pass Ski Area on a site 12 miles south of the valley at an elevation of 7,300 feet. The ski area was tucked into a treed north-facing slope with a 600-foot vertical drop that led down to a protected meadow. For the level of skiing that was going down in California at the time, it was a perfect location.

Badger Pass quickly gained traction as one of the premier ski destinations in California, featuring the first mechanical ski lift in the West. Built in 1935 and called the “Up-ski,” the lift consisted of two cable-drawn toboggans that pulled eight skiers at a time to the top of the ski area. The Up-ski had a capacity of 100 skiers per hour.

Badger Pass had a short heyday, however. By the 1950s, California ski resorts like Sugar Bowl and Mammoth Mountain that featured chairlifts and longer runs had surpassed what Badger Pass could offer guests.

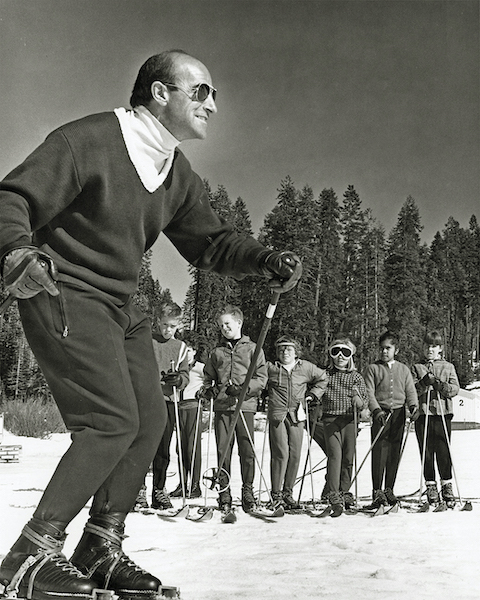

Legendary ski instructor Nic Fiore taught at Badger Pass from 1948 to 2004 and is said to have helped over 125,000 people learn how to ski, photo courtesy Yosemite Hospitality

The National Park Service also played a significant role in Badger’s stagnation as it refused to allow the construction of any chairlifts until 1965. The preservation-minded park service held the position that downhill ski resorts on park land were incompatible with the fundamental mission of the national parks to provide unfettered access to raw natural beauty for personal enjoyment.

But despite resort development getting throttled for the last 60 years, the Badger Pass Ski Area remains open to this day. The resort has stayed alive by focusing on what it has always done best—teaching beginners.

Over the years, the resort’s learn-to-ski programs have remained extremely popular. In the 1980s, when the Badger Ski School was under the direction of ski instructor legend Nic Fiore, it would sometimes teach 900 ski lessons in a single day, according to Gene Rose, the author of Yosemite Winters, the definitive book on the winter sports history of Yosemite.

Badger Pass has no snowmaking equipment and relies on all-natural snowfall, so recent Sierra drought winters have been challenging. But when the resort has snow, it is still one of the best places to learn to ski in California.

“Badger Pass has a great family feel and it’s a very affordable place to learn,” says Lisa Cesaro, Badger Pass’ marketing director. “As a parent you can see all the runs from the deck, so it’s easy for a family to navigate without getting lost like at a big resort.”

Torlano learned to ski at Badger and was the resort’s mountain manager for a few years. He still loves the cozy resort.

“I take my kids there all the time,” he says. “And everyone talks about how tiny it is, but I’ll go there on a pow day and ski from first to last chair and have fun the whole day.”

Going Deep and Gettin’ Rowdy

The 1970s and ’80s marked the start of a new era in Yosemite as cross-country and backcountry skiing became popular.

The 12-mile ski tour out to Glacier Point from Badger Pass was a major attraction, as skiers could stay overnight at the Glacier Point Mountain House or continue on for a few more miles and stay at the Ostrander Ski Hut.

When the snow settled in the spring, experienced ski tourers would ski out of the valley and race across the Sierra to Mammoth, sometimes completing the epic journey in a single day.

Improvements in ski equipment also inspired the leading local skiers of the day to start skiing the improbable gullies that plummet off the valley’s south rim and technical lines on peaks in the national park’s high country near Tioga Pass.

In 1972, Yosemite Village postmaster Leroy Rust and a park ranger named Pete Thompson claimed one of the biggest ski prizes in the valley when they skied the infamous Ledge Trail that drops from Glacier Point to the valley floor near Curry Village. Also known as the Laconte Gully, the run is a steep funnel that ends in a massive cliff that must be avoided by entering a side chute at the bottom of the run.

“There are a lot of great ski lines in the world, but there is no other run quite like Laconte Gully,” says Tim Messick, author of Cross Country Skiing in Yosemite and a former Yosemite ski instructor. “When you are standing at the top of Glacier Point watching the sun come up over Half Dome and turn Yosemite Falls into a rainbow, with a clean, perfect ski run just below you, it’s truly mind-blowing.”

Accessing Laconte Gully, or any of the ski lines dropping off the south rim, requires a 7- to 12-mile ski tour starting from Badger Pass. Finding the top of the ski lines is notoriously tricky, as skiers must navigate several miles through dense forest once leaving Glacier Point Road.

“The first time we tried to ski Laconte Gully, in 1982, we got lost and ended up skiing a gully to the west of Taft Point,” says Messick, laughing at the memory. “We knew we were in the wrong spot, but it was getting dark and we didn’t want to ski back to Badger, so we dropped in and hoped for the best.”

Messick was one of Torlano’s ski mentors. The first time Torlano skied off the valley’s south rim was with Messick when he was 17 and still in high school. Torlano learned the protocols for skiing these dangerous lines from Messick and other local skiers like veteran Yosemite climbing guide Bill Russell.

“We always skin in before dark, click off the headlamps on the rim at dawn, and drop in,” Torlano says about his valley touring strategy. “You don’t want to be in those chutes when the sun hits. As soon as the walls start to warm up, they start shedding the snow and rocks. I’ve been blessed not to have had any close calls with avalanches skiing in the valley, but I’ve almost been hit by rockfall a couple times.”

Zach Milligan follows Jason Torlano’s first tracks down Half Dome in February 2021, photo by Jason Torlano

Jim Zellers drops in on the first unroped descent of Half Dome in March 2001, photo by Richard Leversee

Unlocking Half Dome

Topping out at 8,800 feet, Half Dome is the tallest and most prominent peak in Yosemite Valley. Only one small section of Half Dome’s many faces is low enough angle to ski from the summit. This narrow passage on the dome’s Northeast Face is the location of the Cables Route, where thick metal cables are strung up in the summer to allow hikers to summit the dome without technical climbing gear. In the winter, the upright supports are removed so the cables are laying on the rock face.

After climbing the Cables Route in the late 1990s, Zellers realized that this ramp dropping off Half Dome’s summit might be rideable if it ever received enough snow. But as usual in Yosemite, being there when the snow was deep and stable enough to snowboard down proved a tricky proposition.

“Half Dome doesn’t get much snow to begin with, and what does fall usually gets blown off,” says Zellers. “It was a real challenge to hit it in rideable conditions. I hiked up there six times and got denied. I finally rode it on my seventh try.”

When Zellers rode the line in March 2001, he became the first person to ski or snowboard off the summit without a safety rope. Another Truckee resident, Eric Perlman, had skied down the ramp with his friend Bob Bellman on a rope belay in 1981.

Zellers’ pioneering descent was an inspiration for Torlano, who cut out a magazine photo of Zellers riding the line and kept it as motivation to someday ski it himself.

In February 2021, Torlano fulfilled that dream by skiing the Cables Route unroped with his friend Zach Milligan. After reaching the saddle below the steepest part of the face, Torlano and Milligan continued down Half Dome’s Northwest Face to the valley floor by skiing down a climbers’ access route known as the “Death Slabs.” Their adventurous route was the first complete ski descent of Half Dome.

Like Zellers, Torlano attempted to ski Half Dome several times before he was successful. When he finally pulled it off, he scouted the snow conditions from a plane, and upon seeing the line filled in, he hiked up and skied it the next day.

“I had already skinned up there a bunch of times and turned around,” says Torlano. “One time, there was so much snow that when I took off my skins and started booting up, I sunk thigh deep in loose powder. I stopped right there. It was way too dangerous to go any higher. Another time I hiked up thinking it was going to be perfect. But when I got around the final corner and got a view of the line, it was completely blown off. Zero snow.”

When Torlano successfully skied the Cables Route, the snow conditions were firm and icy—conditions that Torlano describes as “scary.”

Yosemite local Jason Torlano jump-turns into a gully above Tenaya Canyon on the east end of Yosemite Valley, photo by Eric Rasmussen

Go Get It

Scoring first tracks, let alone a first ski descent, is a big deal at just about any backcountry ski destination. So you might expect Torlano to keep his Yosemite ski secrets close to the vest. But he doesn’t stress about sharing reports from his adventures because he knows how hard it would be to ski a new line before him.

“I could tell you exactly where my next dream first descent in Yosemite is, but the chances of someone being there at the right time to do it ahead of me would be so slim,” he says. “It’s not like a rock climb where you are just waiting for a sunny day.”

Torlano has also skied all the obvious lines. The first descents he’s still chasing are lines only a master of the valley’s complex topography could find.

“There are still first descents to be had in the valley, but you’d have to spend a lot of time in the park to find them—just because they are in nooks and crannies and you wouldn’t be able to see them unless you knew exactly where to look,” says Torlano.

Three weeks after they skied Half Dome last winter, Torlano, Milligan and Torlano’s longtime ski partner Eric Rasmussen skied another Yosemite Valley first descent called the Bushido Gully. Torlano says the line, which cuts underneath the Northwest Face of Half Dome, ranks among his favorites in Yosemite.

“We thought the conditions would be terrible, but we ended up finding really nice pow in the gully section, which was a total surprise,” he says.

The 2020-21 winter was not a big one, so the fact that Torlano skied a first descent in powder holds promise for aspiring backcountry skiers who dream of dropping into the valley one day. Zellers, for one, isn’t worried.

“It will happen again. It’s still going to snow. We just won’t have as many of those great days in Yosemite as we used to,” says Zellers. “That’s the disappointing part.”

Messick agrees. It’s still going to snow in Yosemite, and when it does, the skiers who want it the most will be ready and waiting.

“They say that Mary Tressider skied one of the gullies on the south rim in the ’30s in a dress on old-time ski gear,” Messick says with a laugh. “And you gotta believe it. She was an amazing skier who stared up at those walls her entire life. When those gullies are full of snow, they just call you in: ‘Come ski me. I dare you.’”

Seth Lightcap is a writer, photographer and avid High Sierra explorer from Olympic Valley who has experienced some of the boldest adventures of his life in Yosemite.

No Comments