27 Nov Weather Whiplash in Death Valley

From snowstorms to heat waves to torrential flooding, 2023 was one of the wildest years on record in a land famous for its extremes

Looking up to Telescope Peak from 282 feet below sea level in the Badwater Basin, photo by Seth Lightcap

Backcountry snowboarding in Death Valley National Park was not on our bingo card at the start of winter. Yet here we are the first week of April 2023, strapping into our splitboards on the 11,049-foot summit of Telescope Peak, the tallest mountain in the Panamint Range and the national park.

My wife Allison and I are about to ride Telescope’s East Face. Staring down our descent, we can see the Badwater Basin more than 11,000 vertical feet straight below us. With an elevation of 282 feet below sea level, the Badwater is the lowest point in North America, and known for its exceptionally hot and dry climate.

The scale of the view is hard to fathom. As is the unbelievably deep snowpack that sits beneath our snowboards. We’re looking out at one of the hottest and driest places on the planet, but we’re about to drop into a mountain face so caked with snow it looks like a backcountry run at Lake Tahoe midwinter.

The exceptionally deep snow on this towering peak on the west side of the national park is what brought us here from Tahoe. While Telescope’s upper flanks get snow almost every year, the record-breaking storms that buried the Sierra plastered Telescope with one of the deepest snowpacks it’s seen in many years.

There’s no snow in the forecast today, though. It’s gorgeous spring weather—sunny with a slight breeze and skies so clear we can see Mount Whitney to the west and Mount Charleston, a peak outside of Las Vegas, to the east.

The east flank of 11,049-foot Telescope Peak stacked with more snow than it’s seen in years in April 2023, photo by Seth Lightcap

Skinning in the 6-mile approach on mostly crunchy snow, we wonder if the temps are too cool to soften the snow. Atop the face, however, we’re thrilled to find the slope holding perfectly ripe “porn” snow—a high-performance desert snow variety somewhere in between corn snow and hot pow. Snow line is more than 3,000 feet below us, so we’re in for quite the run before climbing back up to the ridge and making our way back to the trailhead.

Before dropping in, we can’t help but remark on the oddity of what we’re about to experience. How can a backcountry snowboarding run in Death Valley look this good? Chalk it up to 2023—one of the wildest weather years in Death Valley’s recorded history. After the exceptionally snowy winter, the park would experience one of its longest and most brutal heat waves ever in July, followed by a weather event in August that would change the landscape forever.

A Heavy Hit From Hilary

One of the biggest snowstorms to hit Telescope Peak in 2023 came on Presidents Day weekend in February. The potent storm caught travelers leaving the Saline Valley, a remote area in the northwest corner of the park, by surprise and buried their vehicles in over 6 feet of snow on the side of a mountain pass. National Guard helicopters had to come to their rescue.

While the debilitating snowstorm was unusual in a region that receives little annual precipitation, the anomalous weather event was all but forgotten six months later with the arrival of Tropical Storm Hilary.

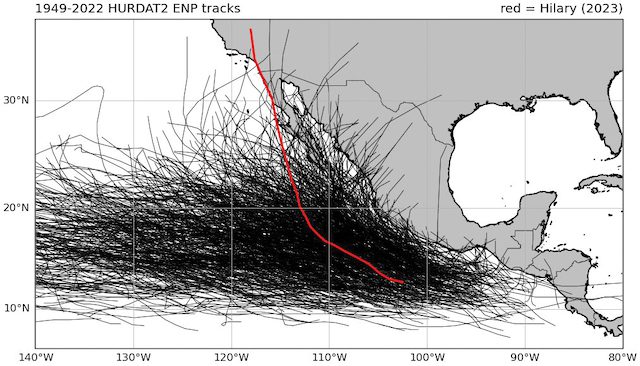

Pacific tropical storm tracks since 1949. Tropical Storm Hilary was the first to track

through the Western U.S. since Nora in 1997, graphic courtesy National Weather Service

Hilary peaked as a Category 4 hurricane before making landfall over northern Baja California as a tropical storm, forcing National Weather Service offices in San Diego and Los Angeles counties to issue their first-ever tropical storm warnings. While it’s not uncommon for the Southwest to receive remnant moisture from tropical events, a storm of this strength had not hit the region since Tropical Storm Nora made landfall in Baja and swept through Arizona in 1997.

The eye of the storm tracked slightly inland and pummeled the San Bernardino Mountains before heading straight for Death Valley. While the winds that came with the storm weren’t incredibly strong, the rain was another story.

“August 20, 2023, was the rainiest day in park history,” says Death Valley Park Ranger Matthew Lamar. “We got over 2.2 inches of rain at Furnace Creek, which is over a year’s worth of rain, in 24 hours.”

Lamar lives in Death Valley and was one of the rangers who helped preemptively close the park before Hilary arrived. But while the National Park Service expected some flooding, they didn’t expect it to shut down the park for the longest stretch since Death Valley was founded in 1994.

Floodwaters from Hilary tore through a dirt road near Furnace Creek, exposing a water line, photo courtesy National Park Service

Hilary’s unrelenting rains caused massive flash flooding that carved up the park’s sprawling network of paved and unimproved roads like a hot knife through butter. Hundreds of miles of roadways were damaged. Several stretches of road were left with 10-foot-deep trenches, while untold miles of dirt roads were completely erased from the landscape by the raging floodwaters.

“Death Valley has seen flooding before, but the difference between Hilary and previous events was that the flooding was more widespread across the entire park,” says Morgan Stessman, a meteorologist with the National Weather Service Las Vegas who forecasts weather for the Death Valley region. “Most major rain events in the past have been more isolated, with flooding only affecting certain regions of the park.”

The road damage was so severe that park officials had no choice but to close Death Valley, with no scheduled reopening. It was an unprecedented result caused by a rare weather event—and one that Daniel Swain, a climate scientist from the University of California, Los Angeles who studies extreme weather put in perspective.

“There has never been a day in recorded history with more water vapor in the atmosphere above Southern California and Southern Nevada,” says Swain.

Not the First Flood

In the wake of all that water, Death Valley remained closed until October 15. When the gates finally reopened, only a fraction of the park was accessible. Hundreds of miles of roads were still damaged or had yet to even be assessed for damage because road crews couldn’t get through flood-ravaged impasses.

Hilary closed Death Valley for nearly two months, the park’s longest closure ever, but it was not the first time flooding has shut down the park. A record-breaking rain event just over a year ago forced its closure as well.

Tropical Storm Hilary washed away long stretches of State Route 190, forcing Death Valley’s longest closure ever, photo courtesy National Park Service

“Hilary beat the previous single-day rain record of 1.7 inches set last year on August 5, 2022,” says Lamar. “Having two historic weather events in back-to-back years is pretty remarkable.”

The deluge in August 2022 was not a tropical storm like Hilary, however. The heavy precipitation was caused by a wave of monsoonal moisture that got energized by a low-pressure system moving across the Southwest. Flash flooding from the event buried over 50 vehicles in mud and debris, damaged hundreds of miles of roads and closed Death Valley for two weeks.

Another major rain event in 2015 caused significant flood damage to Scotty’s Castle, a historic Spanish-style mansion on the north end of the park, which has yet to reopen.

“Death Valley might be the driest place in North America, but it is also a place that has been shaped by water,” says Lamar. “The evidence of that is everywhere you look, from the canyons to the alluvial fans to the salt deposits on the valley floor. The region goes through static periods where you don’t see the effects of weather events, and then you have these big, dynamic events like what we got in August where you see just how impactful water really is in the desert.”

A Death Valley Dream Run

The impact of snow covering all the rocks and bushes on Telescope Peak has Allison and me frothing with excitement as we begin our snowboard descent. We left the truck prepared to pick our way through a rocky, thin snowpack, but there’s no need for tiptoeing down the mountain today.

With a view of the hottest place on earth, Allison Lightcap rips cold turns on the east face of Telescope Peak, photo by Seth Lightcap

The steep chute we ride into is loaded with snow, and some digging around before we drop gives us confidence that it’s stable. With respect for our remote location, we slash turns down the chute one at a time to make sure we both don’t get caught in an avalanche.

After passing through the upper constriction, we pull off to the side of the chute to admire the gnarled trunks of bristlecone pine trees that cling to the cliff bands. We wonder how many winters these ancient trees have been buried in snow up to their upper branches, as they are now.

The second half of the run opens up, allowing us to step on the gas and arc huge turns on the massive walls of the water course. We temper our speed only to take in the otherworldly views of the endless expanse of desert that unfolds below us.

A few hundred feet above snow line, we come to a junction of three drainages that marks the end of our run. A quick traverse allows access to a slightly lower-angle drainage that leads back up to the ridge.

Unstrapping from our boards and gearing up for the climb, we are ecstatic. The run was better than imagined and riding such a unique peak in such epic and ephemeral snow conditions is what we live for.

The climb back to the ridge is longer and steeper than we anticipated, but the weather is still perfect. With temperatures in the mid-50s and a cool breeze at our back, we climb in our sun shirts, barely breaking a sweat. Meanwhile, 8,000 feet below and just a few miles away as the crow flies, thermometers at the Furnace Creek Visitor Center near the Badwater Basin hover around 80 degrees.

Hot and Getting Hotter

Furnace Creek visitors are likely enjoying the relatively comfortable weather as well, as 80 degrees in April is cool for the hottest place on earth.

Furnace Creek is appropriately named, as the temperature supposedly hit 134 degrees on July 10, 1913, a world record that stands to this day. The record is disputed, however, because thermometers of that era were not reliable.

The hottest reliably measured temperature at Furnace Creek was recorded just a couple of summers ago, when it reached 130 degrees on July 9, 2021. The heat that day beat the previous record of 129.9, which was set on August 16, 2020.

While temperatures did not reach 130 degrees in 2023, there was a streak of 17 consecutive days in July that measured over 120 degrees, the third longest such heat streak in Death Valley history. That heat wave peaked on July 16 with a high of 128 degrees.

The recent string of exceptionally hot summers comes as no surprise to Lamar.

“We’re certainly feeling the effects of climate change here in the park,” he says. “Seven of the 10 hottest summers in park history have come in the last 10 years, and we expect that trend to continue.”

While more record heat waves are nearly assured, how climate change will affect precipitation in Death Valley is not as clear-cut.

“With climate change, we’ll likely see a higher probability of major weather events, but that could mean more rainstorms or periods of severe drought,” says Stessman.

Swain agrees and offers an explanation as to why Death Valley will likely see more wild swings between extreme weather events as the planet warms.

“Each fraction of a degree of warming is going to be more painful than the last because the atmosphere can hold 7 percent more water vapor per degree centigrade of warming,” he says. “What that means is that a warmer climate raises the ceiling for how extreme precipitation can become at an exponential rate, and by virtue of that same coin, raises the potential for the atmosphere to extract water from plants and the soil at an exponential rate.

“The reality is, 20 years from now, a summer like this one will feel like a relatively mild summer in terms of both precipitation and temperatures.”

A Long Road of Repairs

Dry weather in September and October was a blessing for the California Department of Transportation (Caltrans) and the National Park Service, as it allowed them to expedite repairs of Death Valley’s most important roads. Caltrans is responsible for maintaining State Route 190, which is the park’s main thoroughfare. The National Park Service maintains all other roads, including nearly 1,000 miles of unimproved backcountry roads.

When Death Valley reopened in October, visitors could enter the park on State Route 190 from the east or west, and access the Badwater Basin.

“With the amount of damage that the park sustained, just getting State Route 190 open was a huge step,” says Lamar. “Now we’re focused on the secondary roads and the backcountry roads.”

The Federal Highway Administration is funding the emergency repair of the paved roads. Popular routes such as North Highway, which accesses the Ubehebe Crater and the Racetrack (the dry lakebed known for its strange moving rocks), plus Emigrant Canyon Road, which accesses the Wildrose Charcoal Kilns and Telescope Peak trailhead, are slated to open sometime after February 2024.

National Park Service crews are working on a few of the more popular backcountry roads, as well. Echo Canyon, Hole-In-The-Wall, Cottonwood Canyon and Marble Canyon roads are scheduled to reopen by January 2024, while a few heavily damaged backcountry roads, including Titus Canyon and Lower Wildrose roads, are not expected to reopen until 2025.

“When you get historic events like this, we wish we could snap our fingers and get the roads open the next day, but that’s just not reality,” says Lamar. “Mother Nature has reset many of the backcountry areas of the park, and it’s our goal to reestablish roadway access to these areas. But we need to do it responsibly so we’re not bulldozing a roadway through a designated wilderness, or impacting sensitive natural resources or important cultural resources.”

Expect the Unexpected

After climbing back to the ridge line, we traverse for a couple of miles to a high point, where we drop in on the final descent of the day. Our last run takes a dynamic route that begins in a rocky bowl before funneling into a creek gully and spitting us out onto a snowed-over road that we cruise down to the trailhead.

On our way out we see a lot more terrain that would be fun to ride if we ever return to backcountry snowboard on Telescope Peak. Which begs the question: Will Telescope Peak ever get this much snow again?

If Death Valley’s roller coaster weather in 2023 is a sign of anything, it’s to expect the unexpected. We won’t be holding our breath waiting for Telescope Peak to hold such prime snowboarding conditions again, but we also won’t be surprised at the day a massive winter storm dumps snow down to the Badwater Basin and puts all the peaks in the national park in play.

Such a snow scenario may be a stretch, but all bets are off with climate change in a region defined by wild weather extremes. So, like the saying goes, if Furnace Creek ever freezes over, we’ll snowboard there too.

Seth Lightcap is an Olympic Valley-based writer, photographer and avid explorer of Sierra rock, snow and trail.

No Comments