25 Jun Webber Lake Opens its Gates

Virtually frozen in time, this former stagecoach stop and fabled fishing lake is both a reminder of the Sierra Nevada’s past and a harbinger of its environmental future

For decades the only things that escaped the gates of Webber Lake were stories and legends—whispers of rainbow trout as large as footballs, a stage stop hotel where Gold Rush miners once mingled with artists and a spectacular meadow that lit up like Fourth of July fireworks each summer.

In the checkerboard of alternating public and private land that dots the wild landscape north of Truckee, the lake was a private parcel close enough to Henness Pass Road to breed stories, but tantalizingly off-limits to the general public.

Then, last year, the gates to Webber Lake swung open. After more than a century of private ownership, the mystery and majesty of a serene and historic Sierra Nevada landscape was unveiled to the public.

Webber Lake is now open for camping and day use, photo by John Peltier

Webber Lake is now open for camping and day use, photo by John Peltier

The Truckee Donner Land Trust purchased the property in 2012 from Clif and Barbara Johnson, members of a sheep-ranching family who owned the 3,000 acres surrounding the lake since 1870. Over the next five years, the Land Trust readied the property to open to the public, revamping the 45-site campground for public use, and adding an ample day-use area for anglers and hikers.

Today, the property is a rarity in the Sierra Nevada. It holds world-class history, wildlife habitat and recreation potential in almost equal measures. But, uniquely, it has seen few visitors since the days when mules and oxen, straining against the yokes of Virginia City–bound haul wagons, clattered by its shores.

“It is without a doubt one of the most precious landscapes we’ve been fortunate to protect. Not just because of its rich biodiversity, but because of its history,” says Perry Norris, executive director of the Truckee Donner Land Trust.

Campers and anglers can experience Webber Lake much like it was 150 years ago, when it was a popular stopover on the supply road between the Sacramento Valley and the booming Nevada silver mines. Its waters still teem with trophy trout—now supplemented by recently planted Lahontan cutthroats. The historic Webber Lake Hotel still stands at its shores, showing the ravages of 158 Sierra Nevada winters in its timbers and roofline. And the wild calls of sandhill cranes still ring out over the lake.

That history, those fish-filled waters and the beautiful landscape that surrounds it are now open for exploration, beckoning a new generation of the general public to create their own stories or fabricate their own fireside tales along its shores.

“Starting as a kid, I’ve camped my entire life and never felt what I feel when I camp at Webber Lake,” says Norris. “It’s a very unique and special place. We intend to do our very best to keep it that way.”

Webber Lake on a windless Sierra Nevada day, photo by John Peltier

Webber Lake on a windless Sierra Nevada day, photo by John Peltier

From Stagecoaches to Sheep

Webber Lake got its name from a fascinating Gold Rush character who rescued orphans, developed early pharmaceuticals and first stocked the lake with trophy trout.

David Gould Webber, a New York doctor who’d come West by way of the Panama Canal, first laid eyes on Webber Lake while reportedly searching for a grove of red fir trees. He laid claim to the land and by 1860 had built a two-story hotel on the lakeshore.

During that time, Henness Pass was quickly becoming one of the main thoroughfares over the Sierra Nevada, a route favored by wagon trains for its gentle grades. At its peak in popularity, the road was so packed with traffic that slower haul wagons traveled by day and stagecoaches traveled by night to ease congestion.

In those days, teamsters mixed with vacationers like renowned landscape painter Thomas Hill in the halls of the two-story hotel. For most of its history, the hotel was a place of rest, reflection and recuperation, with early advertisements heralding the lake’s “health-giving qualities” that “cannot be too highly appreciated.”

But on one infamous day, Webber Lake’s serenity was ruptured by gunshots.

James O’Neill, a disgruntled employee of dairyman and hotel operator Jack Woodward, took matters in his own hands after a dispute with Woodward and shot him to death, according to historical accounts. O’Neill was taken to Downieville to face justice—even though the murder weapon was never found—and became the last person to be hanged on the Downieville gallows. More than 100 years later Webber Lake caretaker Doug Garton discovered a Civil War–era pistol hidden in a well on the property. Today, that pistol is on display at the Downieville museum, as the likely revolver wielded by O’Neill.

Dr. Webber was known for many things beyond the lake and hotel that bore his name. He bred wild horses, adopted or supported as many as 50 orphans, and was a medical doctor famous for creating and prescribing “Webber Pills” as a cure for nearly any illness, according to the Sierra County Historical Society.

Even in the wild Gold Rush days that attracted some of the country’s most colorful characters, Webber was considered a person with “dauntless zeal for odd projects” and described in the Reno Evening Gazette as a man whose “habits were queer beyond eccentricity.”

That originality led Webber through what seems like several lifetimes full of accomplishments—he owned both a flour mill and a sawmill, built the Sierra County courthouse, constructed numerous roads and bridges, served as the Sierra County School superintendent and opened his own pharmacy.

Webber Lake, and nearby Webber Peak, stand as the namesake testaments to the man Webber was, and the recreation potential he saw in the placid, mountain-rimmed waters of the lake, which was named Truckee Lake before it bore his name. The fact that a century and a half later people still pull trout from its waters and camp along its shores—just as Webber had envisioned—would no doubt please the Gold Rush Renaissance man.

But Webber Lake soon succumbed to the tides of change. As the Gold Rush waned, the property became prized grazing ground for sheep, and the Johnson family, well-known ranchers from the Sacramento Valley, purchased the property as summer pasture while keeping the lake as a private fishing resort.

The historic Webber Station Hotel, built in 1860, photo by John Peltier

Protecting the Headwaters

Webber Lake is both a recreation gem and a conservation prize. And it fits like an interlocking piece in a puzzle of conservation purchases the Truckee Donner Land Trust has been meticulously assembling for years.

To the east, the sinuous wetlands of Perazzo Meadows have been protected and restored by the Land Trust and conservation partners. To the south, Mt. Lola rises above the Lahontan cutthroat–filled waters of Independence Lake, another Land Trust conservation purchase. A series of other important meadows and streams, including Coppins Meadow and Cold Stream Meadow, speckle the landscape between Truckee and the Sierra Valley—conserved forever as wild landscapes connected to Webber Lake.

But Webber Lake stands out as a jewel even in this spectacular watershed. Norris calls it both “the grandest prize north of Truckee” and a critical piece of a “20,000-acre conservation effort spanning well over a decade” by the Land Trust and its partners.

Lacey Meadows, photo by Elizabeth Carmel

Lisa Wallace, executive director of the Truckee River Watershed Council, says that connection of large, undeveloped areas of rich wildlife habitat the Land Trust is accomplishing is critical for a wide array of Sierra Nevada animals.

“We are really seeing the importance of that connectivity so that species can move from Independence Lake to Perazzo Meadows and Lacey Meadows,” says Wallace. “We are restoring and protecting those movement corridors.”

The water that spills from the lake almost immediately rushes over 76-foot-tall Webber Falls—a dramatic first few miles for the Little Truckee River. As the headwaters of the Little Truckee, Webber Lake is vitally important to the health of the downstream watershed.

“We highly value the headwaters,” says Wallace. “The headwaters are the source of the water, so if the headwaters are not clean the river system cannot be clean.”

The Watershed Council has already assessed the area around Webber Lake—including Lacey Meadows, which feeds the lake—and discovered opportunities for restoration.

“At Lacey Meadows there is still a meadow, but it has been degraded,” Wallace says. “We have the opportunity to bring it back.”

The Watershed Council is working on restoration plans for Lacey Meadows that will most likely be implemented by 2020, as well as a grazing management plan that recommends ways to balance the legacy of the meadow as grazing land with practices that can safeguard the ecology and habitat of the wetland.

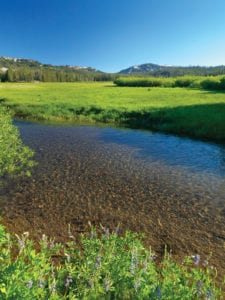

Wildflowers put on a show in Lacey Meadows, photo by John Peltier

Wildflowers put on a show in Lacey Meadows, photo by John Peltier

Open to the Public

Webber Lake opened to the public in no small part because of homemade soup.

Norris and Land Trust colleague John Svahn had dreamed of purchasing and preserving Webber Lake and Lacey Meadows for years, but never considered it a real possibility.

But when they were introduced to Clif and Barbara Johnson, and began bringing homemade soup to the meetings, the conversation soon turned to the future of Webber Lake.

“After a few meetings it became clear that we all wanted the same thing for the property,” says Svahn, associate director of the Truckee Donner Land Trust. “Stewardship of the land for them is a personal pride thing.”

Clif and Barbara Johnson have both passed away, but their legacy is a landscape that will endure. For Clif, who drove sheep from Roseville to Webber Lake across a landscape that today would be impossible to traverse in that manner, the enduring preservation of the lake and meadow mattered more than money.

“We really want to honor their legacy,” says Svahn.

Talk to anyone who has camped at Webber Lake and they’ll try to explain the magnetism of the location. Ken and Joan Bretthauer, the property’s caretakers, have returned to the lake’s shores for 29 summers in a row.

“We spent every weekend in the summer here unless we had to go to a wedding or a funeral,” says Joan Bretthauer.

The Bretthauers are not alone.

“We’re talking to campers, and some are on their fourth generation of camping at the lake,” Svahn says.

That passion for nature—the kind that gets into your blood, changes the way you see the world—is something that Webber Lake has served up in heaping helpings for at least the last century and a half. A New York doctor might have been one of the first to be intoxicated by Webber Lake’s gin-clear waters. The Johnsons might have followed in those same land-loving footsteps. But a whole new generation will most likely kick off their own Webber Lake love affair this summer at the lake’s new campsites.

“For a number of our staff, including me, camping as a kid, getting out of town, sleeping on the ground, hearing owls at night, was life changing,” says Norris. “We all have our story. But it is the root of creating a deeper appreciation for our good earth, and creating future conservationists.”

To book a campsite at Webber Lake, go to tdlandtrust.org.

David Bunker is a Truckee-based writer, editor and nature lover who thoroughly enjoyed his visit to Webber Lake.

Gretchen (Brown) Hayhurst

Posted at 21:53h, 25 MarchI have many memories of Webber lake including helping the Johnsons with the sheep. My Mom and Dad were personal friends of Clif and Barbara and even honeymooned there in 1946. I was born in 1948 and my first trip to Webber was in 1949. Then every summer and every deer season we would spend it at the Lake. We would either stay in the Buckhorn cabin or the huge Glass House, which sadly is no longer there. I haven’t been in quite awhile but hope to visit soon and I will bring some of the photos taken during our vacations. I used to love it when Vern Johnson would show me bullet holes in the walls of the saloon which became his office. I’ve hiked the mountains surrounding the lake and one time we stumbled on the old mining camp. Many wonderful memories and I am so glad it is being restored for future generations.