06 Dec Grooving on the Go

How the Astraltune progressed from an innovative idea in the mind of a young freestyle skier to become the world’s first portable music player

The ability to listen to music whenever and wherever you want, at least by 2021 standards, is relatively unremarkable. However, this wasn’t always the case. Before smartphones became home to vast libraries of music, there were mp3 players, some more memorable than others. Microsoft’s Zune. Sandisk’s Sansa. The iPod, of course. Before that, there was the Sony Discman, and before that, the Sony Walkman. But to reach the true genesis of the portable music player, it is important to travel back even further, to the winter of 1973, when the idea of listening to music on the go was just that: an idea floating around inside the head of a college student from Orinda named Andy Bowers.

“I thought, ‘Man, what I really need is to have my favorite music pumped into my ears to accelerate my skiing,’” he says.

Andy Bowers is in his 60s now. He splits his time between Reno and an island off the coast of the Philippines. But back then, when the idea first struck, he was a business major at Utah State with an entrepreneurial spirit and a keen interest in freestyle skiing.

As an experiment, he purchased a tiny stereo and packed it into a ski-patrol belt. To keep his earphones from falling out, he wrapped a bandana around his head.

“Away I went,” he says. “And I loved it.”

Shortly after, he invited his older brother Roy out to Snowbird ski resort to share his new contraption. By the time Roy reached the bottom of the slope, he was quiet. In the Bowers family, he was very much the pensive, contemplative brother.

“You know,” Roy finally said, “if we built this really high-quality, we could sell them.”

“That was that,” says Andy. The birth of the world’s first portable music player.

Of course, that wasn’t that. If anything, that was just the beginning. What Andy Bowers had built was only a prototype. It didn’t even have a name yet.

Courtesy photo

From Dream to Reality

While Andy Bowers went overseas to study abroad, Roy kept tinkering with the idea. Their father had connections in the auto-electric and manufacturing industry, so he spent some time experimenting with how to take his brother’s prototype and turn it into something marketable.

What he settled on was an automotive cassette deck that he safely tucked into a polycarbonate case with room for rechargeable batteries. His mother worked on sewing pouches that could be used to strap the budding invention to a person’s body.

L.C. Bowman, who often skied at Palisades Tahoe (then Squaw Valley), had put together his own prototype around the same time.

“Some friends and I cobbled together a similar type of thing, only not as a good,” he says.

Instead of a car cassette deck, Bowman used an old Ampex cassette recorder that had been in the family. It wasn’t anything high-tech, and the batteries gave out often, but it worked well enough to allow him to listen to the Grateful Dead on those gloomy days on the mountain.

The first time Bowman saw the Bowers brothers’ invention out in the proverbial wild, he thought two things. For one, he and his friends weren’t crazy for believing that people wanted to listen to music while skiing. Rather than feeling envious, Bowman experienced a kind of affirmation. It really was a good idea.

The other thing that immediately caught his attention was the name the Bowers boys gave their portable music player: the Astraltune.

It was the kind of name that took its inspiration from concepts of astral projection and casual dalliances with psychedelic drugs. It was the 1970s, after all.

The first time Marshall Behling remembers encountering an Astraltune, he was skiing at Palisades Tahoe in January of 1975. In the Chamonix Tavern, he ran into Roy Bowers, who was showing off some of the first prototypes.

Behling and Roy had already been friends from their time together at the University of Nevada, Reno, but it was the Astraltune that eventually pushed them into becoming business partners.

“I was starting my MBA at San Francisco State and needed a product to work on for a class,” Behling says.

He pitched the idea of using the Astraltune, and Roy gave him the green light.

Once they had a feasible product, they hit the road and traveled to some of the major ski shows in California.

“It was incredibly well-received,” Behling says. “We sold out before the end of the show in San Francisco.”

In the early days of the business, there was no advertising budget to speak of. In fact, there wasn’t even much of a business. Instead, there were just a couple of guys hauling an invention around from slope to slope, resort to resort. It was an effective sales method, at least in the beginning. But as the popularity of the Astraltune grew, one thing became clear: Its founders needed to grow with it.

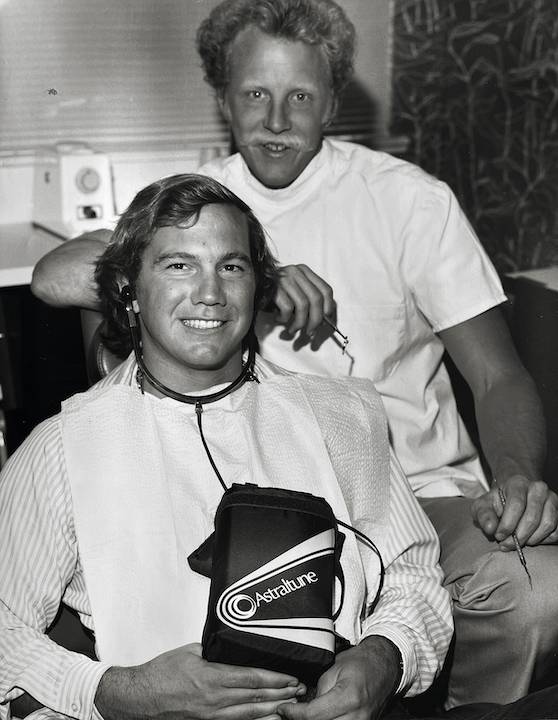

Bob Howard, a professional freestyle skier from Reno, skis at Alta, Utah, with an Astraltune strapped to his chest, courtesy photo

Finding its Niche

In 1975, Bob Howard made the decision to quit playing football, drop out of Santa Rosa Junior College and pursue his dream of becoming a professional freestyle skier.

Technically, there’s a long and rich tradition of students dropping out of school to pursue their dreams. Willie Nelson left Baylor after two years to devote himself to music in the 1950s. Bob Dylan did the same thing a few years later at the University of Minnesota. Even Sylvester Stallone left the University of Miami to chase an acting career in 1969. So, by the time Bob Howard made his decision, he really was in good company.

His parents, however, completely disagreed.

“My family was just appalled at the fact that I didn’t graduate from college,” says Howard, a Reno native who went on to become one of the most recognized freestyle skiers of his era. “My dad told me, ‘You’re not going to get any money. You’re on your own from this point on.’”

Cut off from financial support, Howard sought out someone—anyone—to sponsor him as a skier. That’s what led him to a little warehouse in Reno run by Roy Bowers and Marshall Behling.

“They wouldn’t give me money, but they gave me five Astraltunes,” Howard says. “And they said if you can’t sell four of them for 200 bucks, then you’re a crappy salesman and you better get out of the business now.”

The first model of the Astraltune came with orange Sennheiser headphones and sold for around $185. Accounting for inflation, that’s just shy of $1,000 in 2021. Even with the high price point, Howard didn’t have trouble selling them.

Whenever he traveled to freestyle competitions, he packed as many as he could into his suitcases. He sold the stock across Europe.

For Andy Bowers, this kind of person-to-person sales was one of the best parts of the job. He would go skiing in places like Portillo, Chile, with the Astraltune and, when wealthy Argentines or Brazilians stopped to ask him what that strange gadget strapped to his chest was, he always did the same thing: He took his headphones out, put them into their ears, and watched their faces light up as soon as the music hit.

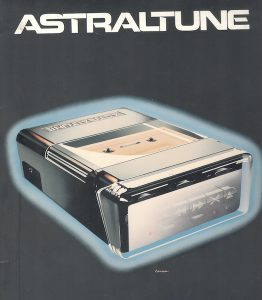

An Astraltune in its signature blue carrying pouch, courtesy photo

In this way, Astraltunes pretty much sold themselves. Their novelty alone was hard to ignore.

“I was in Breckenridge and I saw people skiing with this blue thing,” says Steve Leigh, a hotel owner in New York. “I didn’t really know what it was and I couldn’t get up close enough to see what it was. And then, a couple of days later, I was at Steamboat Springs and I saw the same thing again.”

The blue thing, as it turned out, was the Astraltune’s signature carrying pouch. As soon as he was able to find one, he bought it and spent the rest of his trip wearing the Astraltune on the slopes.

Leigh instantly fell in love with his new portable music player, which he brought home to New York. It was there that he and his friend Stan Cohen decided to track down whoever made this strange and fascinating machine and find out how they could get in on the ground floor of the business.

“So that’s what we did,” Leigh says.

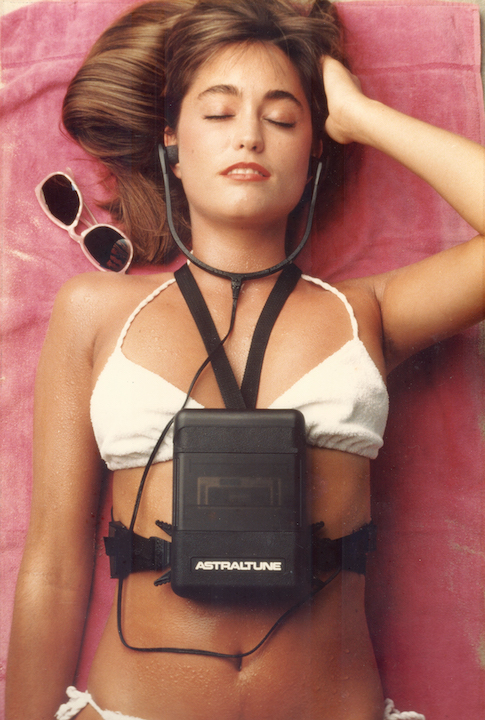

In the late 1970s, Astraltune President Marshall Behling began investing more heavily in advertising in major ski magazines, courtesy photo

A Tough Sell

Leigh and Cohen flew out to Reno and met with Roy Bowers. They purchased a couple dozen units and had them shipped back to New York, with plans to introduce them to the East Coast market.

However, the Astraltune didn’t immediately appeal to the average consumer. Leigh and Cohen walked around Manhattan trying to convince department stores to carry it, but no one seemed interested. Bloomingdales said no. Even Crazy Eddie, an electronics store founded in Brooklyn that grew to have 43 locations at its peak, wouldn’t take a chance on the personal stereo from out West.

“It didn’t work out great,” Leigh says.

They made a few sales here and there, but their inventory remained mostly undisturbed.

Even if Manhattan wasn’t enamored with the Astraltune, sales were still going strong elsewhere.

“Marshall signed on as president and things really started changing then,” says Andy Bowers.

Beginning in 1978, Marshall Behling invested more heavily in advertising in publications like Ski Magazine and Powder. He also sent Andy on the road to not only sell Astraltunes, but to also establish a sales force across the country.

As the business grew in those first few years, two things became clear: One was that the Astraltune was overwhelmingly popular with skiers everywhere (Andy sold out whether he was in the Midwest or New England), and the other thing was that the Astraltune seemed to be overwhelmingly popular only with skiers.

When Behling attempted to take the product to consumer electronics stores, he encountered the same issues that Leigh had in New York. It seemed like the rest of the world just wasn’t that interested in listening to music on the go.

This lackluster response revealed less about consumer desires and more about the design constraints of the Astraltune itself. In its first iteration, the product weighed 3.5 pounds and was sometimes likened to wearing a dictionary on your chest. Its size was a product of the fact that it had been designed sturdy enough to survive both the harsh conditions of high-elevation mountains and the kinetic athleticism of freestyle skiers and downhill racers. Without the protective casing and chest harness, what were you left with? A vulnerable personal stereo that could break as soon as you took your first tumble on the slopes. Who wanted that?

As it turned out, quite a few people.

In 1980, the Bowers brothers and Behling headed off to the Consumer Electronics Show in Chicago, where they rented a booth for the Astraltune. They traded off shifts over the course of the show, with one of them managing the booth while the others went off and explored. Upon returning from one of these walkabouts, Behling delivered a cryptic message to Andy.

“He said, ‘Andy, go look at the Sony booth.’”

So, Andy did just that. That’s when he saw the one thing that would change everything.

“There,” says Andy, “was the Walkman.”

An early Sony Walkman, which the Astraltune team first saw at the Consumer Electronics Show in Chicago in 1980, courtesy photo

Aced by a Tech Giant

The origin of the Sony Walkman—where the idea initially came from—is contested.

One version of the story claims that the Walkman came into being because Sony co-founder Akio Morita thought it would be nice to listen to music while playing tennis or skiing. Another version posits that, during a factory visit, a Sony worker told Morita that he wanted to listen to music while working on the assembly line. A third version, and the one that appears in Morita’s own autobiography, explains that Sony’s other co-founder, Masaru Ibuka, wanted a portable way of listening to music that was lighter and less clunky than Sony’s existing TC-D5 cassette recorder. The task fell to Kozo Ohsone, the general manager of the Tape Recorder Business Division. He would alter the Sony Pressman, a compact cassette recorder released in 1977.

However, Behling has a different theory altogether.

“We had dedicated stores that sold and rented the Astraltune in Venice Beach, Sun Valley, Squaw Valley, Boreal and Aspen,” says Behling. “It was the Aspen GM who called me up in 1979 to say Akio Morita, the president of Sony, had just bought an Astraltune.”

Maurice Barnwell, the author of Design and Culture: A Transdisciplinary History, echoes a similar claim in his book, though he cites the year as 1978.

The story of Morita’s fabled ski trip to the Rocky Mountains is nearly impossible to verify. Still, it remains an enticing tale even decades later, in part because of the timing of Sony’s own portable music player, which first went on sale for around $200 on July 1, 1979, in Japan. In 1980, it was released in the U.S. under the name the Soundabout. In the UK, it was the Stowaway, and in Australia, the Freestyle. However, the name that eventually stuck, the one that is forever synonymous with changing the way people listened to music, is, of course, the Walkman.

Leigh and Cohen, the young entrepreneurs who once attempted to take over the New York market, also believe that there is a connection between the Walkman and the Astraltune, whether direct or ethereal. Cohen thinks Morita copied the Walkman. Leigh thinks that a buyer at Bloomingdales may have taken the idea to Sony after refusing to purchase Astraltunes from them.

Even Andy Bowers believes that the existence of two similar machines cannot be explained as mere coincidence.

“All of this is documented in a Playboy magazine article,” Andy says.

He can’t recall which issue, but he does remember an extensive interview with Morita.

As it turns out, the issue came out in August 1982. The front cover announces an interview with “the man who put earphones on the world—Sony’s Akio Morita.” Open up the magazine and, on page 9, you’ll find an advertisement for the Sony Soundabout. Flip to page 69, and there appears the interview for which Playboy contributing editor Peter Ross Range spends two weeks in Tokyo with Morita, “in chauffeured cars, on a tennis court, over lunch, and even in a steaming Japanese bath.”

The conversation between Range and Morita is far-ranging, and explores everything from trade policies, labor relations, the atomic bomb and, yes, even the Walkman.

What Morita tells Range is similar to what he published in his autobiography a few years later. However, what is more interesting is the conversation that Range and Morita ended up having about broader concepts like invention, innovation and creativity.

For instance, Range says there are a lot of people who think that “the Japanese are not truly innovative but only cleverly derivative”—in other words, superb imitators.

“Such a perception gap is a cause of big problems,” Morita responds. “Western people criticize the Japanese effort as lacking originality. But Picasso was influenced by Lautrec and Beethoven learned much from Mozart.”

“What’s your point?” Range asks.

Basically: Everyone is influenced by someone else.

Last-Ditch Efforts

Regardless of which story is true, after they discovered the Walkman at the Consumer Electronics Show, the Astraltune team was on red alert.

“We locked ourselves in a suite at Caesars Palace for three days,” Andy says.

They spent that time fervently brainstorming, drawing up timelines and deadlines, and refining designs for new prototypes. By the time their emergency strategy session ended, they had settled on one approach moving forward: They would go for the high end of the market.

In late January of 1982, Astraltune ran an ad in the Reno Gazette-Journal announcing an immediate opening for an electronic technician with expertise in both “theory and trouble-shooting of solid-state circuitry.”

“We were taking a huge leap from modifying an automotive cassette deck to designing printed circuit boards,” Andy explains. “We had always relied on using somebody else’s product that we just modified.”

What they ended up with was the third-generation Astraltune Stereopack. Announced in a 1982 press release, it was advertised as being 40 percent smaller than the earlier model and around 50 percent lighter. The one-year warranty had been extended to two. It also featured a one-piece harness that was now detachable, a high-frequency noise filter and a water-resistant polyurethane case that could survive the toughest of weather conditions.

What the Astraltune could not survive, however, was the free market.

There was no one thing that killed it. Instead, there were multiple interconnected factors and decisions, including missed opportunities and logistical issues, that had steadily accumulated since the business’ inception.

For instance, when the Astraltune was still relatively young, Behling and Roy Bowers got some bad legal advice that ultimately resulted in them not pursuing a patent for the device.

There was also the simple, inescapable fact that, even in the 1970s, Sony was already a giant in the technology and electronics industry. The first model of the Walkman, the TPS-L2, had sold tens of thousands of units in its first few months alone. The second-generation Walkman, which was released in 1981, went on to sell a couple million units.

By the time Astraltune got into manufacturing its third-generation music player, the company encountered a steady stream of quality-control issues that led to missing out on the entire 1981 Christmas season.

“In the ski industry, if you miss Christmas, you’re pretty much toast,” Andy says. “That began the downward spiral.”

Just under a year after announcing the release of the third-generation Astraltune, the company made another announcement of an entirely different sort.

In late February of 1983, it ran an ad in the Reno-Gazette Journal for an auction at 650 South Rock Boulevard: the Astraltune building.

Office furniture, tools and equipment were all up for sale—the assets of the company behind the world’s first-ever, nearly forgotten portable music player.

A Trend Endures

On the surface, it might not seem like the Astraltune had much of an impact on the world.

From the time of its incorporation to the auction of its assets, the company existed for just under a decade. Soon after Astraltune closed its doors, the Sony Walkman took its place as the unofficial portable music player of the silver screen.

In Footloose, released in 1984, Kevin Bacon can be seen scooting rhythmically around town with a Walkman clipped to his hip. Five years later, the Ghostbusters used a Walkman WM-B39 to broadcast Jackie Wilson’s Higher and Higher to the population of New York City and, in doing so, brought the Statue of Liberty to life. Even Chris Pratt, the leading man of the 2014 blockbuster Guardians of the Galaxy, listens to the first-generation Walkman while traveling between the stars. Ironically, if we’re going by name alone, the Astraltune would have been a far better fit for a franchise about an intergalactic superhero who can’t get enough of his retro cassette player.

One thing that these movies have in common is their shared portrayal of music as something both magical and transformative. Songs have the power to change minds, bring inanimate statues to life and chart paths across the universe. While the Walkman may have been the medium for this message, the message itself has its roots in the creation of the Astraltune.

Sony’s choice of the name Walkman implied a vision of the future in which portable music was so ordinary and accessible as to be made synonymous with the activity of simply walking around. The name Astraltune likened the experience of listening to music to one rooted not in the body, but in the soul. It suggested that something as simple as hearing your favorite song had the ability to transform you, if not forever, then at least for a few minutes.

The act of listening to music on the go is, at least by today’s standards, remarkably ordinary. Even I sometimes forget that I have my Bluetooth headphones in while walking through the aisles of the grocery store. The music has the tendency to fade into the background of whatever it is I’m doing. However, there are those rare moments when an unexpected song fills my ears and, suddenly, the mundane is imbued with the kind of cosmic significance that makes it feel as if I’m the star of my own movie. Perhaps you know the feeling: when the rhythm of the music aligns perfectly with the rhythm of your body in such a way that you feel in tune with both yourself and the universe.

This is what the Bowers brothers, and Behling, had in mind when they brought the Astraltune into being—that music is fun and metamorphic and groovy—and that everyone deserves the chance to be reminded of that whenever, and wherever, they want.

That idea still survives today, even if the Astraltune itself went out of business a long, long time ago.

Matt Jones lives in Sparks, where he can often be found wandering around with his headphones in his ears.

M landolina

Posted at 12:01h, 01 FebruaryI invented this way before these guys in the mid 60’s. I hooked up an 8track with 8-d batteries and a dc converter. Wow, what a trip it was, skiing on the slopes!!!

Allan

Posted at 20:49h, 23 AprilAndy Bowers is still a successful man happily living in his private island with his loving wife. I’m proud to know them count them among my friends