25 Jun The Pandemic that Paralyzed Truckee

The Spanish flu hit the young railroad town particularly hard during the snowy winter of 1918-19

In the Iliad, the ancient Greek poet Homer describes the god Apollo bringing the plague to an unsuspecting town in the following manner:

Like night he came and sat beyond the ships and shot his arrows and his silver bow howled. First he struck the mules and running dogs, then turned his piercing weapon on the people and pyres were always burning, piled with corpses.

Aside from the aptness of likening a plague to the approach of a night filled with arching arrows, the passage attests to the mere fact that virulent epidemics have been with human beings and our communities since the dawn of time.

The Iliad was written 3,000 years ago. There have been many plagues since, carrying with them varying degrees of devastation.

Even a thoroughly modern concern like Truckee has had its bouts with global pandemics in the past. In fact, as of this printing, the novel coronavirus pales in comparison to the health devastation of the Spanish flu of 1918, which ripped through Truckee beginning in October 1918 and continued to rage throughout much of that difficult and snow-laden winter.

As of this writing, Nevada County has seen under 100 infections and only one death—a minor event compared with the epidemic that walloped Truckee in the autumn of 1918, when the town reported 46 cases in a week at one point. In fact, most of the town’s residents fell ill, particularly during the bleak January of 1919, when a series of heavy winter storms rendered the population housebound and easier prey for a flu virus that preferred closed quarters and crowded indoor places.

Lake Tahoe was generally spared due to its relative remoteness combined with the fact that the timber industry had died out at the lake while its next chapter as a playground for the rich and famous had yet to commence.

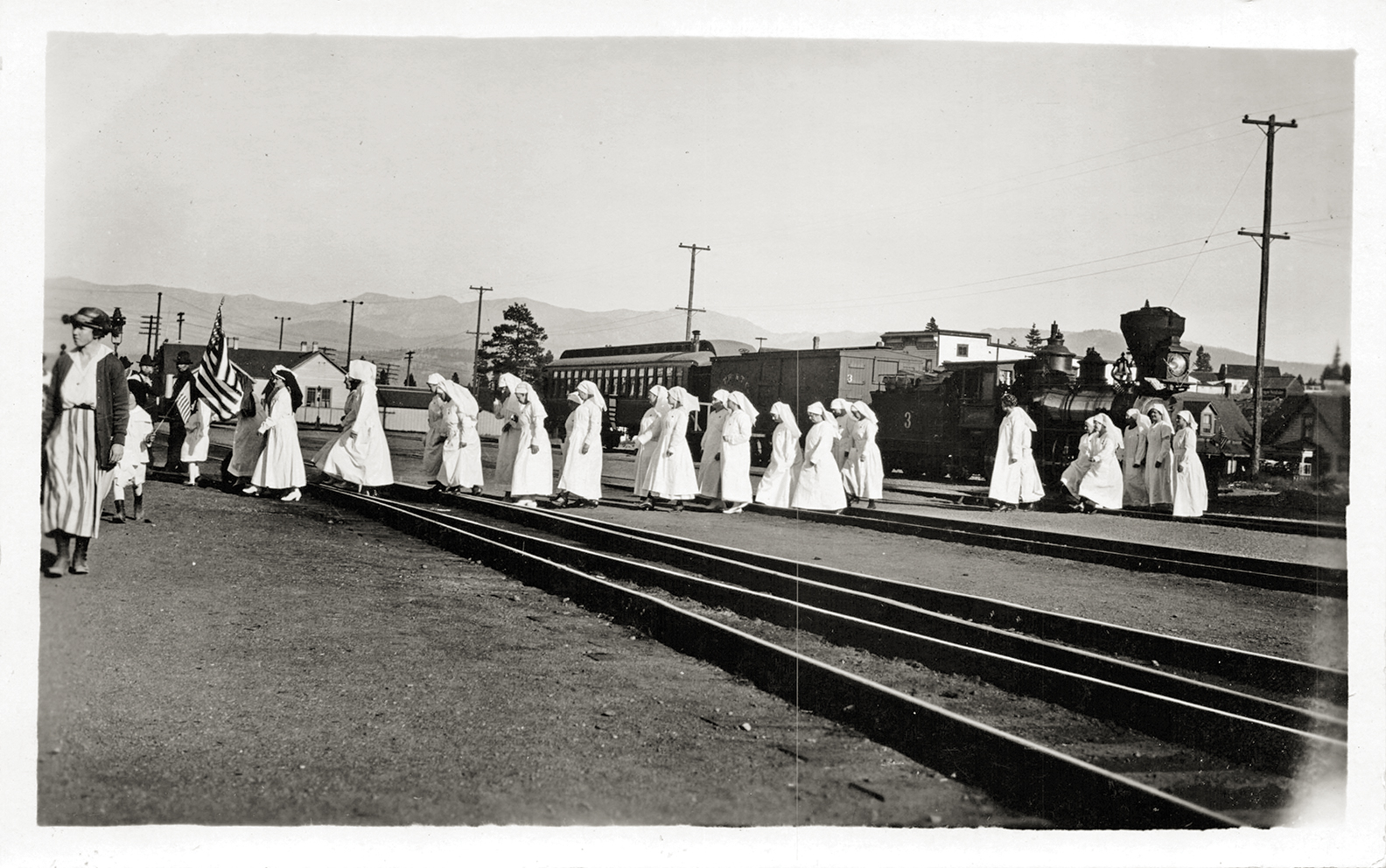

But Truckee served as an important stop on the railroad line and as such was susceptible to the ravages of the pandemic.

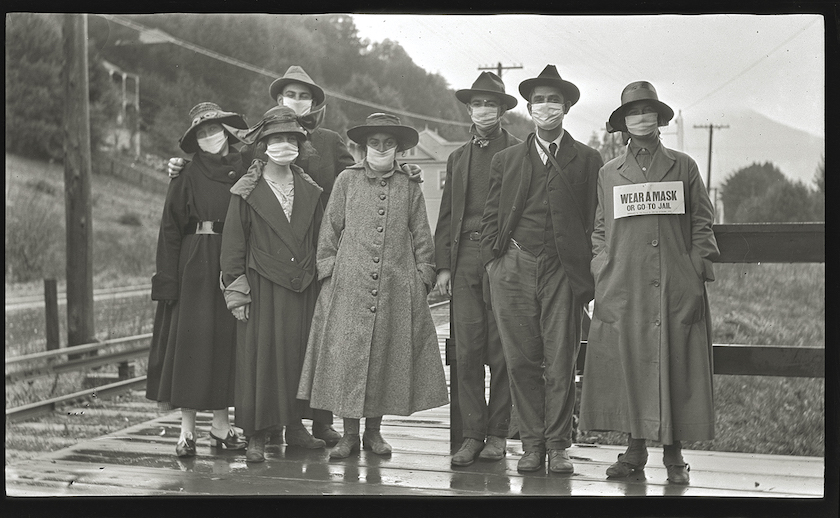

People stand outdoors wearing masks in Mill Valley, California, on November 3, 1918, photo courtesy Annual Dipsea Race

Stricken Down

There is no telling how many people died in Truckee, but those who lived through the epidemic said it was higher than any other time in the town’s history.

Worldwide, the Spanish flu killed anywhere from 17 million to 50 million people, although many of those died due to secondary infections or malnourishment due to overcrowding and poor hygiene at hospitals.

Regardless, the death toll was staggering, with some estimates asserting as much as 6 percent of the world’s population succumbed to the disease beginning in the spring of 1918 and lasting until the early summer of the following year.

In Northern California, the deadly period of the disease started on September 23, 1918. According to San Francisco newspaper reports, the outbreak began in the city after a man who had recently returned from a business trip to Chicago displayed flu symptoms.

The Spanish flu had already been around other Western cities like Denver and Kansas City during the summer, but it was a typical flu that preyed on the very young, the very old and the infirm. But the second wave that began in earnest in the autumn was different and it caught the notice of health officials.

The San Francisco Public Health Office immediately quarantined the stricken businessman, hoping to nip the epidemic in the bud.

No luck.

By October 9, the city reported 169 cases of influenza. Three days later, the California state board of health reported 4,000 cases throughout all of California. By October 16, San Francisco saw its numbers skyrocket past 2,000 cases and the epidemic had come, quiet as night.

Meanwhile, in Truckee, the local newspaper published an article on October 10 telling people to avoid breathing on each other while keeping appropriate physical distance.

“DON’T indulge in promiscuous coughing or sneezing,” read an editorial in the Truckee Republican.

Around this time, Dr. Frank Baxter, who sat on the Nevada County Board of Health, surmised the pestilence would soon come to the mountain town by way of the railroad.

On October 14, a man in Colfax died of the flu.

Three days later the health board issued an edict that banned all public gatherings and closed most commercial enterprises except for select times in the day. Even the saloons were instructed to turn out the lights by 6 p.m.

G.W. Bryant, a health officer living in Truckee and one of two doctors operating in the area, recommended closing the schools. The churches in and around Truckee were advised to suspend their services until after the epidemic calmed or to conduct them, to the extent possible, in the open air.

The number of infected began to grow and there were five deaths in Truckee in late October as many of the most prominent people in town, including Dave Cabona, Dr. Earl McGlashan and F. Finnegan, became ill.

On October 23, Rudolph Summers, a 23-year-old serving in the Army at Camp Kearney near San Diego who grew up in Hobart Mills just north of Truckee, died from the flu.

In a way, Summers encapsulated the victims of the second wave of the Spanish flu. Unlike ordinary victims of the flu, he was neither very old nor very young, nor was he immunocompromised or otherwise ill.

In fact, the Spanish flu preyed on the vigorously healthy, using their own immune systems to attack them in what is called a cytokine storm.

The Spanish flu killed mostly young people in the full bloom of their life.

Some 99 percent of those who succumbed to the disease worldwide were under 65 and half of all deaths were people ages 20 to 40. The pattern held true locally, where Nevada County records indicate one-third of all deaths were people between ages 20 and 40.

Origins of the “Spanish” Flu

The reasons why the Spanish flu ravaged this age group are debated, but one of the strongest hypotheses settles on World War I and the nature of trench warfare as the culprit. With most cases of the flu, the most virulent strains induce people to stay home, while the people with the mildest strains are able to leave home, go out into public and pass it around, thereby causing a weaker and less pestilent form of the disease to evolve through the population.

But the nature of trench warfare created a different scenario, where soldiers with the worst form of the flu were transported to busy and crowded military hospitals that lacked proper hygiene, meaning that the worst, most deadly strain of the flu virus propagated throughout the population.

The Spanish flu is poorly named, as it is not believed to have originated in the European country. It was so named because, unlike England, the United States and France, which censored news about the outbreak to not dent morale as World War I persisted, the Spanish press gave heavy coverage to the pandemic.

In the United States, the so-called Spanish flu is thought to have first appeared in a U.S. Military outpost in Kansas. Other virologists have theorized the disease spawned in a contingent of British troops living at a staging area with a military hospital in Etaples, France. Some believe the disease came from China and was brought to Europe and America via Chinese laborers.

Truckee Suffers

Regardless, young Rudolph Summers was emblematic of the flu’s preferred prey in that he was a young soldier.

The disease continued apace in Truckee. On October 24, the Truckee Republican ran an editorial demanding that all Truckee residents and visitors wear a mask over their face.

“The man or woman who will not wear a mask is a dangerous slacker,” the paper blared. Medical professionals were particularly insistent in this regard.

Dr. Joseph Bernard, who became the town’s only doctor when he arrived in Truckee at the turn of the century, joined forces with Dr. Bryant to minister to the sick. Many sick individuals were taken off the train at Truckee and had to be treated in a small hospital that was created in a Victorian home in Brickelltown.

Bernard caught the flu and was out of commission for days, while Bryant fought the disease valiantly throughout the homes of the Truckee denizens afflicted by the disease. He nearly worked himself to death during the plague, according to Judge Fosten Wilson.

“He once went to Hobart Mills by sled to treat a sick man,” Wilson wrote. “The man was taking some medicine another doctor had given him and Dr. Bryant threw it out in the snow and applied mustard plaster to the man’s chest. The next day, the fever broke and the man recovered. There were no antibiotics and the methods of treatment were primitive. I think it was faith that healed the man.”

Bryant died of a different flu strain in 1922, but many in the town said his fight with the flu in 1918 weakened him to the point where he was more susceptible to a different permutation of the disease.

Bernard and Bryant weren’t the only victims.

As October 1918 progressed into November, Father Michael O’Reilly, the town priest, died of the flu after spending the preceding weeks attending to the sick and dying.

Millie Tappendorf, the daughter of a prominent Truckee family, died on November 7, just one day after her oldest daughter’s funeral. Her husband and four of her six daughters survived.

By January, the toll of the sick and dying was compounded by severe weather as the mountain town was repeatedly battered by heavy blizzards.

Truckee resident Marjorie Zoebel, who was a young girl at the time, provided the Truckee-Donner Historical Society with an account of the event:

“Most of the residents were down. The few that were still on their feet and able to carry on made gallons of soup and shared it with neighbors who were less fortunate.”

Zoebel’s father, Peter Fay, was an engineer for the Southern Pacific railroad and he came down with a bad case of the flu in January.

“In time I learned that my father had passed away,” Zoebel said. “Charlie Ocker, the undertaker, came and took dad away before I was allowed downstairs.”

Zoebel recalled that the incessant storms blocked the way for trains, meaning supplies were scant and there were not enough caskets for the dead. They had to lay her dead father on the couch until a casket arrived, and even then, wood was so scant they had to hold up the casket with broomsticks.

In January, Dr. Earl McGlashan was stricken ill. McGlashan was the only son of Charles Fayette McGlashan, one of the most prominent men of early Truckee, a landowner and town promoter, and editor of the Truckee Republican.

Earl McGlashan grew up in Truckee and earned a license as a dentist before moving to San Francisco to open a practice. After he became sick in January 1919, he was severely weakened. He began to recover over the course of the year before his fortunes reversed and he died in December 1919 at age 37, yet another victim to the worldwide pandemic.

“Several months ago he was in Truckee, full of life and apparently in the best of health, now he lies cold in death in San Francisco,” the Truckee Republican read in December 1919.

By February the collective fever that hung over Truckee finally broke. Schools reopened, saloons turned on the lights past 6 p.m. and the congregants crowded into the pews again on Sundays.

Forgotten by History

The Spanish flu, despite being one of the deadliest pandemics in human history, is often called “the forgotten pandemic.”

The reasons are many.

Unlike the Black Death, the most fatal pandemic in human history that killed one-third of Europe’s population, the Spanish flu in its most virulent iteration only lasted about nine months. The Black Death lasted four years.

Also, the early twentieth century was replete with killer diseases, as yellow fever, typhoid, diphtheria and cholera were all around and equally as lethal, perhaps dulling the comparative impact of the flu.

Finally, the outbreak happened in parallel to World War I, a belligerent battle of world powers that resulted in enormous casualties for all sides and dominated the front pages of newspapers the world over.

But in Truckee, many remember the heavy toll of the Spanish flu. The disconsolate families of the many victims in Truckee, in California and throughout the world stood as a forlorn testament to the inordinate virulence of the Spanish flu that convulsed the world beginning in 1918.

Information for this article came from the Truckee-Donner Historical Society and its research.

Matthew Renda is a Santa Cruz–based writer and former Tahoe resident.

No Comments