04 Apr Wild Western Art

American realism artist Charles Muench is a man of the West. A resident of Gardnerville, Nevada, he hunts, fishes and has backpacked the Sierra Nevada since childhood.

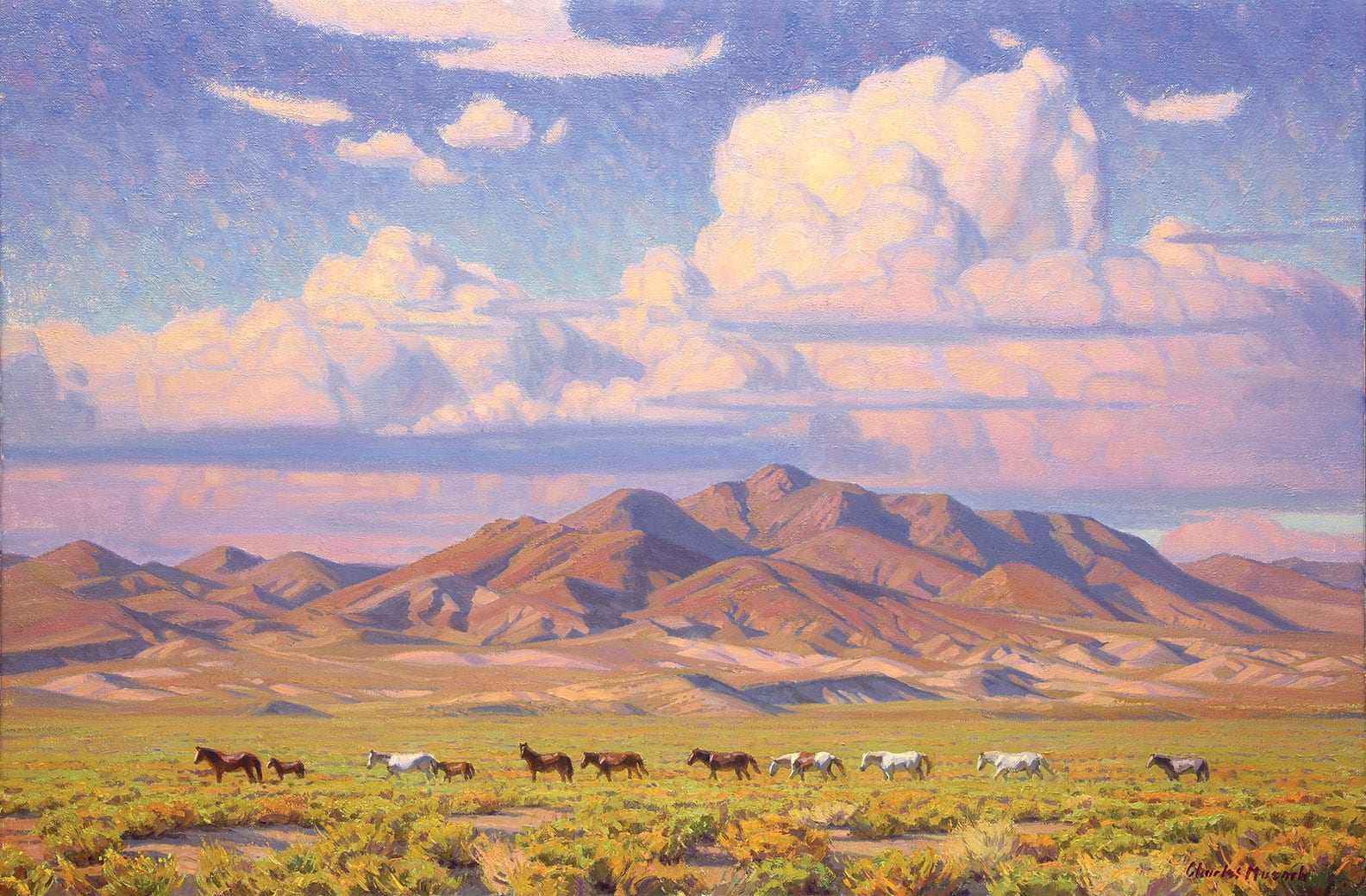

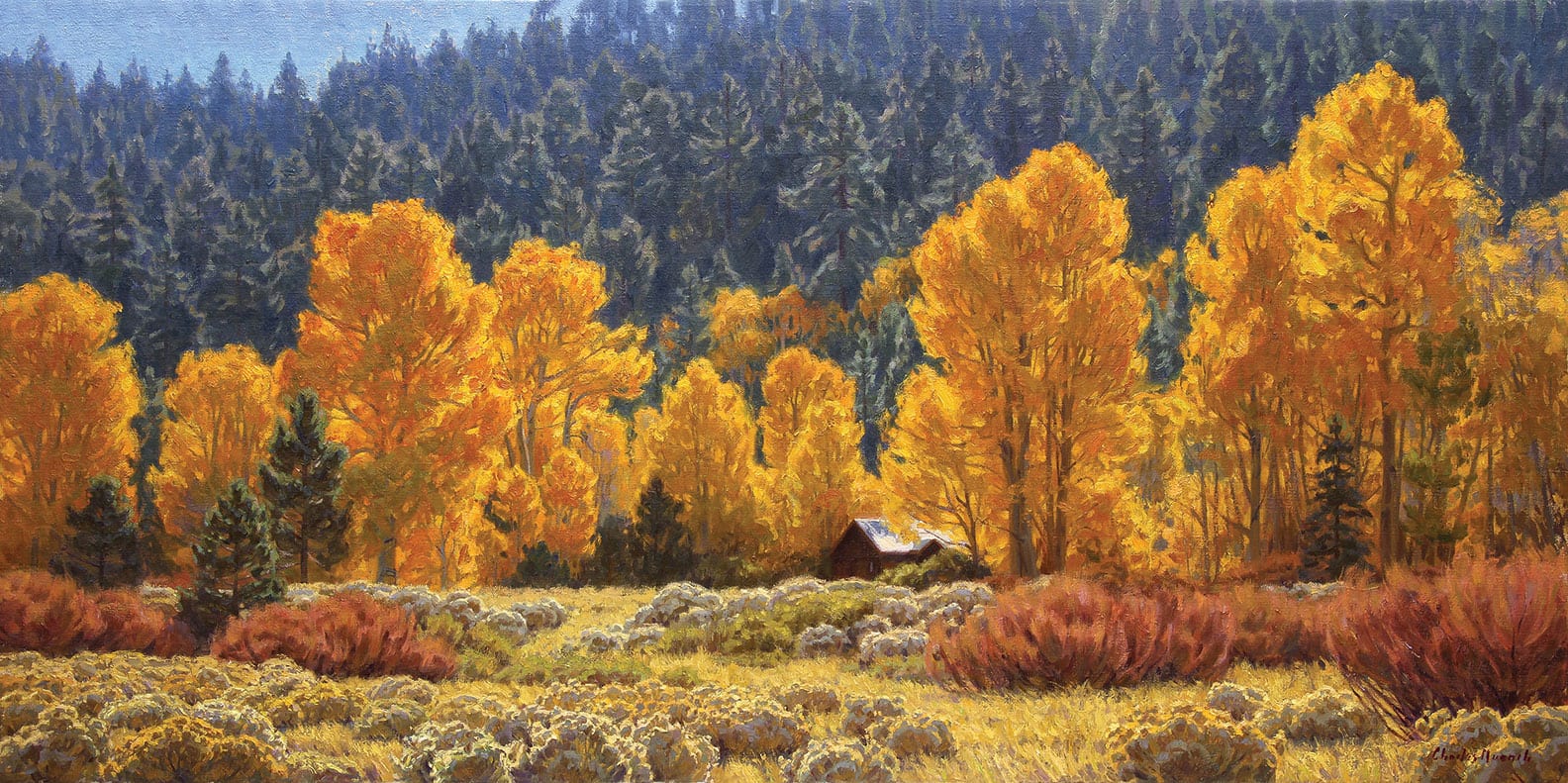

Like his life, Muench’s work captures the essence of the rugged West—Nevada cowboys riding in from the range, wild mustangs grazing in high desert sagebrush, ghost towns and gothic crags.

Art Education

At age 6, in 1972, Muench moved to San Jose, California, with his mom, dad and two brothers. He recalls there were “a few more orchards and less computers.”

At age 15, Muench entered an art contest. His oil painting of a cable car lumbering up a quintessential San Francisco street garnered him second place. Muench earned $1,500 for his painting. He knew then art would be his career.

“Art is my calling,” he says. “I’m a nicer person when I paint.”

After high school, Muench attended the University of California, Santa Barbara, on a writing scholarship. The art department left him flat. He listened to music students across the hall practicing, repeating the same chords over and over, and thought, “Whether you play rock, blues or jazz, you’ve got to know the chords.”

He says, “It was more of a paint-what-you-feel type of school. Many artists say they’re self-taught. Would you go to a self-taught doctor? In his garage he says, ‘Hey, let me take a look at your spleen.’”

Muench transferred in 1985 to San Jose Sate, where he studied under professor Maynard Dixon Stewart—named in honor of the famous Depression Era painter. He refers to Stewart as the “Yoda to [his] Jedi.”

Muench appreciated Stewart’s precise critiques. He might note, “You’ve missed the grace of the pose; the model is leaning on her left leg, not the right.”

A student in Muench’s class once lamented, “You’re crushing my creativity,” to which Stewart responded, “If a little discipline will crush your creativity, perhaps it’s not strong enough to foster.”

Muench attended every class Stewart offered, for credit or not, and graduated from San Jose State in 1988 with a Bachelor of Fine Arts.

He moved to New York, where he attended the Art Students League of New York and the National Academy of Design. He also studied in the atelier of acclaimed art instructor Michael Aviano before eventually returning to California.

Finding His Niche

To supplement his passion in the early years of his career, Muench worked in the service industry, bartending and waiting tables in the Bay Area. He likens the work to how he paints: five or six projects at a time.

“You see table number one needs water; table number five has finished their dinner,” he muses. “You can’t be linear. You have to keep your eye fresh.”

From initial inspiration to the conclusion, each painting has its own personality, Muench says. “Sometimes it finishes itself, some are grinds—arduous. Like road trips, some end in disaster.”

However, Muench has gotten over the angst of failure. “When I realize the painting doesn’t have a pulse, there might be a brief gnashing of teeth, a momentary curl in the fetal position,” he says. “But if I could go back in time to fix a compositional flaw, I’d stop the Lincoln or Kennedy assassinations, something of greater importance.”

Muench lived through the first dot-com boom in San Jose from 1992–2001. He taught classes from his north-lit warehouse studio in the old fruit canning section of the city. Later, he participated in many plein air shows. It was a nice income source and served as additional education. The work, however—finishing a painting outside, on the spot—was exhausting, he says.

His true Western epiphany came in the year 2000 on a backpacking excursion over Kearsarge Pass, an imposing granite facade of crags and pinnacles at the eastern edge of Kings Canyon National Park.

Dusted from the trail, Muench popped out of his tent and thought: “I need to immerse myself in this and live in the Sierra.”

Sierra Light

Sierra Light

“The Range of Light,” as John Muir coined the Sierra Nevada, is the perfect place for an artist. “[The light] changes with the time of year—the clearness of a fall day, summer moisture in the air—it doesn’t lend itself to pictures,” says Muench. “You’ve got to be in it to understand.”

Muench captures the Eastern Sierra’s craggy escarpments with American realism technique. Brushstrokes have a dual function. They represent the subject, while still interesting for their texture, value and color. Look closely and one can see the palette knife used for heavy paint, or brushstrokes scraped across dry paint, creating layers.

“Brushstrokes are the footsteps of an artist’s emotion,” Muench says.

Muench prefers Belgian linen canvas, stretched horizontally to give it a little “tooth.” It is archival and lasts for hundreds of years, as opposed to cotton, which is brittle and can crack.

Tahoe Overlook, a 40-by-30-inch oil on linen, stems from a conversation with nature. A flat knife-stroke smooths into aqua Tahoe water, bumped-up white paint thatches conifers in snow. Reddish-brown, ochre, tawny and near-black slashes transform brushstrokes into logs.

“Some people only paint the concept,” says Muench. “You have to get your boots on the ground in observation. Every pine tree is not a Christmas tree. It’s a combination of understanding the principles of light, atmospheric influences, and applying that principle to what you see visually.”

When he’s not in the outdoors, Muench can often be found in his Gardnerville studio, working intensely.

“All I do is paint. I don’t check emails in the studio, or keep my cellphone there,” he says. “Art is that that conceals the labor.”

He paraphrases W. Somerset Maugham, the famed British novelist: “I only write when inspiration strikes. Fortunately, it strikes every morning at nine o’clock sharp.”

Accolades and Awards

Muench’s work has long been recognized nationally. This past December, his work was included in the exhibition Small Works Great Wonders at the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum in Oklahoma City.

His painting Sierra Cathedral, meanwhile, will be included in the historic California Art Club’s 106th Gold Medal Exhibition in April 2017 at the Autry Museum of the American West in Los Angeles.

Sierra Cathedral is Muench embodied: In the darkened foreground is a lone rider with his pack mule. The view of Kearsarge Pinnacles looms breathtaking—monumental gray geometry sliced with snow. The 32-by-40-inch oil expresses the linen’s woven texture in the clouds—pinks, breathy light blue and white strokes, roughed by the canvas.

“The Sierra backcountry, with its gothic shapes and spires, evokes similar emotions to those experienced in the presence of the great cathedrals of Europe,” says Muench. “This rider with his pack mule, tired from the switchback trails of Kearsarge Pass, cannot help but feel truly humbled in the presence of this Sierra cathedral.”

While Muench has received many honors over the years—including the Patron’s Choice Award at the Maynard Dixon Country Invitational in 2005, 2008 and 2013—his favorite award is from a third-grade dental calendar contest entry. He drew a momma bird feeding her babies in the nest, replete with toothbrush and toothpaste, titled, After Every Meal, Brush.

He still relishes the thought of his ice cream bar prize.

Amy Edgett is a freelance photojournalist who lives in Floriston. To view more of her work, visit 360Pixie.com, or contact her at 360pixie@sbcglobal.net.

The Artist

Charles Muench

(775) 265-4454

www.charlesmuench.com

No Comments