15 Feb Mending Van Norden Meadow

Conservation efforts seek to return Donner Summit wetland to its original biologically rich state

Randy Westmoreland is walking across uneven ground, striding through the brown blades of dormant winter grass. His eyes are trained on the rise and fall of the earth, picking up the course of a long-lost stream among spindly lodgepole pines and leafless willows. He traces a faint, abandoned watercourse out toward Van Norden Meadow, the expansive Donner Summit meadow system that forms the headwaters of the South Yuba River.

“This has all been modified, so you have to look for the pieces of evidence,” says Westmoreland.

After 32 years at the U.S. Forest Service and nearly two decades specializing in the hydrology of meadow systems, Westmoreland sees things that the untrained eye would never catch. Faint dips show where a healthy, braided stream system once cut through an alluvial fan of rich sediment. Granite boulders signal the ancient edges of glacial detritus. These faint remnants of a healthier past of one of the Sierra Nevada’s largest subalpine meadows are glimmers of hope. And a team of hydrologists, scientists and conservationists are working hard to turn those promising signs into the full-fledged rebirth of an iconic and resilient meadow—which was purchased for preservation by the Truckee Donner Land Trust in 2012 and transferred to the Forest Service in 2017.

Randy Westmoreland of the U.S. Forest Service walks through Van Norden Meadow on Donner Summit, photo by David Bunker

Van Norden shares a history with hundreds of Sierra Nevada meadows. Nature spent millions of years crafting the wetland into some of the most biologically rich habitat on the planet. Receding glaciers scoured cobbles and boulders into the depression of Summit Valley, covering them in gravel. Water cascading off of mountain peaks flowed into sinuous streams that filtered sediment from the water and fed willows and sedges. Within this ecological hotspot of rich diversity, plants and animals flourished.

Then, over a period of mere decades, the entire system was upended. Ranchers cut a ditch into the meadow to dry up soggy soil and expand pasture. The railroad rerouted tributaries and funneled them into culverts. County roads created more culverts and ditches to channel streams. And a dam submerged a large portion of the meadow.

The delicate web of water that was the lifeblood of a thriving mosaic of fens and sedges became a type of natural sluice box, shunting water through the meadow as fast as possible. Where water once soaked into sponge-like soils, dry patches of ground emerged. As a response to this changing ecology, lodgepole pine saplings venture further and further into ground that was once too wet for tree roots.

“As I learn more about the meadow systems across the Sierra Nevada, that is the pattern I see,” says Sarah Yarnell, a scientist with the Center for Watershed Sciences at U.C. Davis who is studying Van Norden Meadow’s hydrology. “They were beautiful. They had water. You could put roads there. The meadows systems across California have all been hit that way.”

Despite all of these environmental indignities, the meadow is still breathtakingly beautiful and incredibly rich. Thousands of toads hop through the meadow, birds molt and fatten for migration, and 115 different types of butterflies flock to its sedges and streams. Even after decades of degradation, nature’s powerful forces are still at work. And that offers hope for a stunning story of environmental regeneration and renewal.

Westmoreland’s job is to give nature the chance to regenerate itself further, and reclaim its past glory. A lot of that involves walking the landscape and using precise elevation readings to determine the courses that water took for thousands of years before a rancher or road engineer with a shovel or backhoe forced it into an unnatural ditch.

“I am out here trying to find out what was here, and what went wrong,” says Westmoreland.

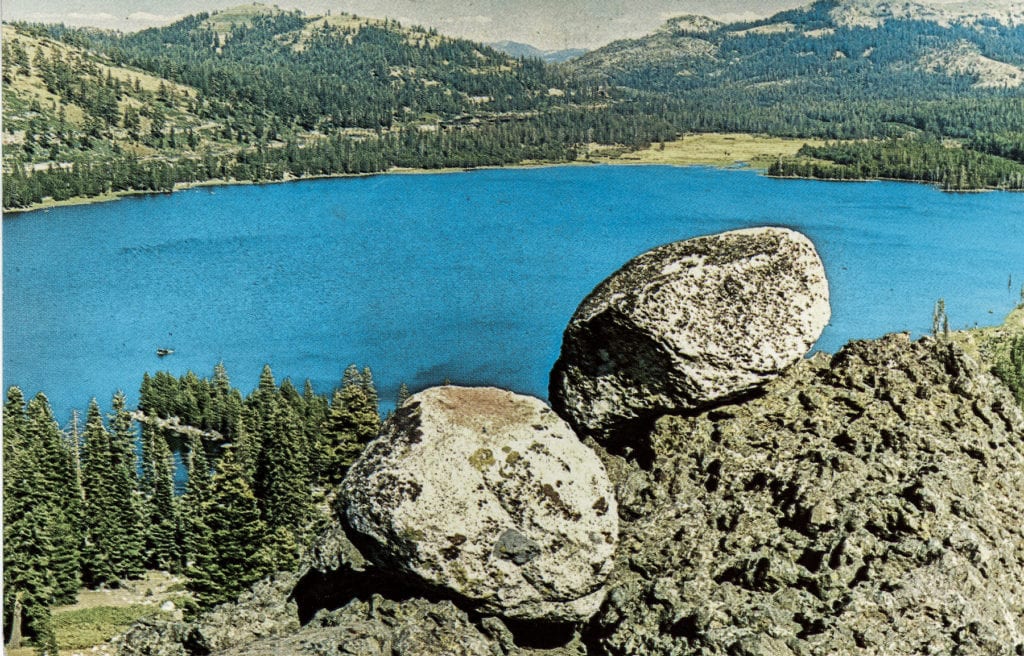

The expansive Van Norden Meadow system forms the headwaters of the South Yuba River, photo by David Bunker

The expansive Van Norden Meadow system forms the headwaters of the South Yuba River, photo by David Bunker

A Reservoir Reversed

In the history of the Sierra Nevada, meadows often become reservoirs, but rarely is that transformation reversed. That, in itself, makes Van Norden unique.

A dam was first built in Summit Valley as early as 1874, according to the Donner Summit Historical Society—likely to supply water for hydraulic mining or to harvest ice. By 1916, the Pacific Gas and Electric Company had taken ownership of the dam and enlarged it. For the next 60 years, the meadow was submerged, becoming a popular boating and waterskiing reservoir named Lake Van Norden. But by 1976 the dam was deemed unsafe, and it was notched to release most of the water. A small, residual lake still backed up behind the notched dam.

As the reservoir waters receded, the meadow sprang back to life. Now, restoration will take it the next step, rebuilding its natural function.

The reservoir reversal comes at a time when a national dialogue is mounting over the removal of dams. Documentary films like the Patagonia-funded Damnation have sparked growing interest in reconnecting salmon spawning runs blocked by dams and restoring free-flowing rivers. This momentum has increased since the successful removal of the Elwha Dam in Washington—the largest dam removal in the nation.

This timing will make the Van Norden restoration of particular interest as scientists and conservation advocates study what happens when a dam comes down. The outcome could influence meadow restoration projects across the Sierra Nevada as interest mounts in removing dams and restoring wetlands.

“There are many other meadows that were dammed and turned into reservoirs,” says Rachel Hutchinson of the South Yuba River Citizen’s League. “Some of them have failed and turned back into a meadow, but none that have been purposefully restored, so this is a great learning tool for us.”

Lake Van Norden filled a significant portion of Summit Valley from 1916 to 1976, when its dam was notched to release most of the water. Note a ski jump in the bottom left of the photo, courtesy Norm Sayler, Donner Summit Historical Society

Lake Van Norden filled a significant portion of Summit Valley from 1916 to 1976, when its dam was notched to release most of the water. Note a ski jump in the bottom left of the photo, courtesy Norm Sayler, Donner Summit Historical Society

An Invasive Obstacle

While the road to restoring Van Norden Meadow starts with water, one thorny obstacle has reared its head. Reed canary grass, a fast-growing invasive species, has spread throughout the meadow. Some fear that if the invasive is not dealt with, the improved growing conditions after the restoration will allow the invasive species to flourish, choke out native species and dominate the meadow.

The Forest Service and partners at the South Yuba River Citizens League are studying how best to deal with the invasive plant.

“In the last several years it has really expanded,” says Hutchinson. “The first couple times I went there, it was just in small patches, but now it pretty much covers the channel. It is really a problem.”

Potential solutions include mowing and perhaps even targeted applications of herbicide, but Hutchinson and other partners are geared up for a sustained multi-year effort to fight the aggressive grass. They hope to beat back the invasive species enough to allow native species the chance to gain ground against the invader and restore the diverse patchwork of sedges, willows and grasses that are native to Van Norden.

“No one wants a monoculture out there,” Yarnell says. “Natural meadows are diverse.”

Recreation abounded on Lake Van Norden for over 50 years. Here, anglers target catfish, photo courtesy Norm Sayler, Donner Summit Historical Society

Recreation abounded on Lake Van Norden for over 50 years. Here, anglers target catfish, photo courtesy Norm Sayler, Donner Summit Historical Society

A Climate Solution

Restoring a meadow in the age of climate change takes on new intricacies. Researchers who observe species moving to higher elevations as temperatures rise see this large, soon-to-be-lush meadow as a rare chance to restore a subalpine refuge for a wide variety of plants and animals.

“If species are really going to start moving higher because it is hotter and drier at lower elevation, having Van Norden functioning as an ecosystem will give them somewhere to go,” says Hutchinson.

Ryan Burnett, Sierra Nevada group director for the conservation science organization Point Blue, has studied how birds use the meadow now and how the bird population could respond to a rejuvenated meadow. He sees birds as an indicator of broader ecological health.

“We think birds are indicating for a lot of things. They are pretty high up in the food chain. They are at the same level fish would be,” says Burnett. “They indicate for habitat structure, but also function.”

Burnett sees both hopeful signs and indications of the vast potential of the meadow system in the yellow warbler, Lincoln’s sparrow and Wilson’s warbler that flit through the meadow.

“I think it has the potential to be one of the more resilient meadows to climate change,” says Burnett. “It could be a standout star as far as the bird community.”

Burnett notes that the large volume of water that filters through the meadow, as well as its size and elevation, make it unique and important. It also has the potential to become habitat for the willow flycatcher, an endangered Sierra Nevada bird that nests in willows that hang over standing or slow-moving water.

The elusive flycatcher has been seen in Perazzo Meadows, another recently restored meadow system north of Truckee. And any increase in the bird’s numbers would be a big victory for the species, which is teetering on the edge of extinction.

“I think we can make a difference today for the meadow bird community, and I think we can make a huge difference tomorrow when there is less water late in the summer,” says Burnett.

Meadows, with their natural absorption of water and slow release of stream flows throughout the summer, could be a critical line of defense against coming changes in climate. But widespread restoration will need to be conducted to meet this goal.

According to a report by the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation, “of approximately 330,000 acres of meadow distributed in more than 10,000 meadows across roughly 20 million acres of the Sierra Nevada, only approximately 30 to 40 percent of meadow habitats exist in a non-degraded state.”

“The two most threatened or imperiled things in the Sierra Nevada are meadows and aspen groves,” says Perry Norris, executive director of the Truckee Donner Land Trust, which led the conservation purchase of the meadow.

While significant groundwater monitoring and research is already being conducted in Van Norden Meadow, the hydrologic restoration will most likely not begin until 2019, says Hutchinson. That’s when the main stream and tributaries will be put back in their natural channels or altered to once again function as the life-giving artery of the meadow before ditches and diversions harmed the meadow.

Then, nature will take its course. And conservationists hope years from now, hikers, motorists and bird watchers will experience one of the largest subalpine meadows in the Sierra Nevada in a state it has not been in since the mid-1800s.

“Every indication is that this is going to be a pretty phenomenal recovery of something that has been messed up for 150 years,” says Norris.

David Bunker is a Truckee-based writer.

Lisa

Posted at 15:55h, 02 MarchGreat story and good to see the by-line of David Bunker again!