15 Feb Vikingsholm Retains Historic Charm on Tahoe

Almost 90 years after it was built, the mansion on Emerald Bay remains a shining example of Scandinavian architecture

Helen Henry Smith remembers weaving between the thick trunks of towering pines as summer dusk fell through the forest and twilight grew on the surface of Emerald Bay, darkening the sky over Lake Tahoe.

Smith had the good fortune to spend portions of her first 14 summers at Vikingsholm, the fantastical Scandinavian-style castle tucked into the northwest corner of Emerald Bay.

“I spent many happy years there,” Smith, now 86, says from her Palo Alto home.

Smith’s luck was connected to her mother’s close friendship with an affluent woman named Lora Knight, who used her wealth for a variety of progressive causes, including underwriting college scholarships for women.

One of the women Knight selected for a scholarship was Smith’s mother, but this arrangement only commenced what became a lifelong friendship between the two women.

“Mrs. Knight was a very warm person,” Smith says. “Some of my happiest memories are playing double solitaire with her as a child. She could be an astute card player.”

Through those early associations, Smith came to learn the history of the castle by the bay.

Helen Henry Smith, right, attends a Vikingsholm fundraiser, photo courtesy Sierra State Parks Foundation

Helen Henry Smith, right, attends a Vikingsholm fundraiser, photo courtesy Sierra State Parks Foundation

Emerald Bay’s Castle

Knight built the 38-room mansion, which she christened Vikingsholm, in 1929. Knight had bought 239 acres in Emerald Bay the previous year from the William Henry Armstrong family with the intention of building a summer home.

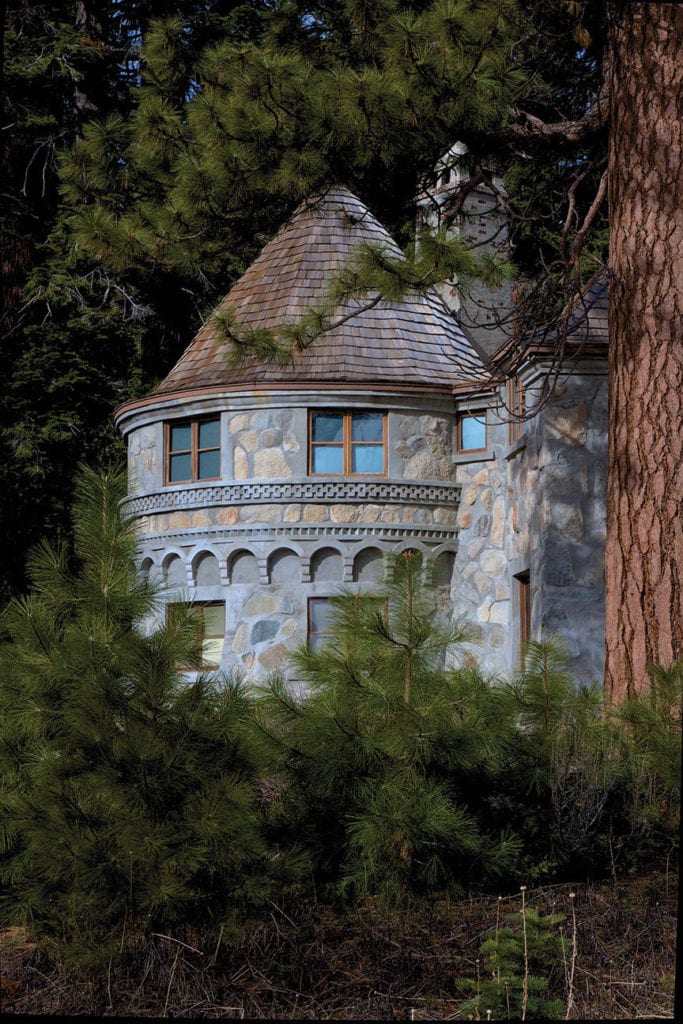

The builders used almost exclusively local materials, including copious amounts of colorful granite and several slats of timber that comprise the exterior of the structure.

“It is considered one of the finest examples of Scandinavian architecture in the United States,” says Heidi Doyle, executive director of the Sierra State Parks Foundation. “The mansion incorporates a multitude of Scandinavian architectural elements.”

Most notably, architect Lennart Palme took inspiration from the peasant huts that dotted his native Sweden in constructing a sod roof on one portion of the building. Another portion of the roof used large timbers collected from the site and took cues from Scandinavian fortresses.

The central part of the house has standard shingles, functioning as the calm center of the eclectic and ornate stylistic flourishes that flank it.

Muscular granite boulders enshrined in mortar echo the stone churches and castles that flourished in Northern Europe as early as the eleventh century, contemporary with the late reign of the Vikings.

Interspersed in the rugged rock are massive timbers, hewn from hand and resounding with the reverberations of Norsemen who would tackle large evergreens to use in construction of their farmhouses and villages.

Elaborate dragon carvings cross each other at roof peaks, accompanied by other intricate carvings distinctive of Scandinavian construction and decoration.

One of Vikingsholm’s dragon carvings, photo courtesy Sierra State Parks Foundation

Norse Lake Tahoe

Many incorrectly assume Knight’s ode to the Norse is due to her Scandinavian ancestry. But she was of English blood, Smith says. Knight did, however, tell guests that Emerald Bay reminded her of the picturesque fjords that she had seen on her many visits to the Scandinavian countries.

“She was a very extensive traveler,” Doyle says. “The deep blue sky, the gorgeous colors of The Lake and the mountains thrusting out of the water in Emerald Bay reminded her of the fjords of Norway.”

But Smith says there was another, more familial and pragmatic reason for Vikingsholm’s decidedly Norse flair.

“Her niece, who she was very fond of, married a Swedish architect,” Smith says of Palme, who had built a Scandinavian-style home in Rye, New York, for his bride. “Mrs. Knight had visited the home and thought this style of architecture would be appropriate for Emerald Bay. So she contracted Palme as the Vikingsholm architect.”

Vikingsholm was the crowning achievement for Palme, who went on to design and build private homes, mostly in the Santa Barbara area where Knight would winter. Palme’s creation at Lake Tahoe became a prototype for the rugged style of architecture that conveyed a simplicity and elegance but was also capable of withstanding year after year of punishing winters and sun-drenched summers.

“It was an early prelude to what we call the Tahoe rustic design, with the use of natural elements, stone and timber,” Doyle says.

The rock used to build Vikingsholm was quarried on site, photo by Rob Retting/Sierra Nevada Ad Partners

Interior Charm

Like the exterior, the Scandinavian leitmotif is also present throughout the 38 rooms of the stately mansion.

Knight commissioned 200 people to help build Vikingsholm, which explains how it was completed just one year after laying the foundation in 1928. While many of those workers concentrated on the structure itself, other craftsmen were hired to incorporate fine detail throughout the interior.

“There is metallurgy built and installed throughout the house. Much of it was created on site,” Doyle says.

Each door is fitted with a unique lock, many of which were based on designs Knight saw while touring museums in Sweden and Norway.

Large, finely wrought paintings are hung on the walls and ceilings, the fireplaces are distinctively Nordic and in the central dining room, two intricately carved dragon beams span the spacious chamber. Most of the furnishings carefully selected by Knight still remain.

“Despite the fact that the house changed hands two more times after Mrs. Knight passed and before the state parks took it over in the 1950s, most of the furniture was left intact,” Smith says. “This is fortunate because the furnishings were of Scandinavian design carefully chosen to match the ambiance of the home.”

Vikingsholm is now a national and state historic landmark, with daily tours in the summer, photo courtesy Sierra State Parks Foundation

Vikingsholm is now a national and state historic landmark, with daily tours in the summer, photo courtesy Sierra State Parks Foundation

Returning to Vikingsholm

After her 14 years at Vikingsholm, Smith didn’t step foot on the property until many years later, and then only by a series of serendipitous events.

Knight had died in 1945 at age 82. Smith’s mother moved on and Smith’s only connection to Vikingsholm were increasingly tenuous if fond memories.

“After Mrs. Knight passed, we lost all contact,” she says. “But then in the 1950s our babysitter just happened to bring us a newspaper announcing that the California State Parks had taken over Vikingsholm. She asked me if I’d ever seen the place.”

By now, Smith was married with a family and pursuing a doctorate in education at Stanford University. But her curiosity and a strong sense of nostalgia drove her back to visit.

When she arrived at Vikingsholm, she says the mansion was much in the same shape as she’d last seen it. But the information the parks system had about Knight and the grounds was often mistaken, in some cases egregiously.

“The parks described Mrs. Knight as a notorious socialite,” Smith says. “Well, she had money, of course, but she was more of a forward-thinking person. Her main interests were focused on environmental, educational and community issues.”

Far from throwing parties with champagne and tinsel, Knight preferred to surround herself with a well-known coterie of family and friends. As Smith alludes, much of her time was occupied with progressive causes, such as women’s education. She also was one of the primary financial backers for Charles Lindbergh’s nonstop solo flight across the Atlantic Ocean in 1927, and was one of the founding members of the Sierra Club. Knight’s environmentalist tendencies were such that she had Vikingsholm designed around the existing trees on the property.

But Smith noticed other errors, like a wall plaque claiming the mostly local materials were imported from Norway.

Another misconception was that Knight constructed Fannette Island’s famed Tea House for daily afternoon teas. While Knight did commission the Tea House’s construction, her sojourns to Lake Tahoe’s sole island were rare.

“She went out there once, at most twice, a summer,” Smith says. “She was 65 when Vikingsholm was built and most of her guests were older. It was rare that they climbed the island.”

Rather than simply correct the parks service and move on, Smith instead managed to convince one of the Sierra State Park rangers to let her guide tours at the increasingly popular tourist destination.

“I was the first woman to have a field position of this kind with state parks,” Smith says.

Vikingsholm is now a national and state historic landmark. Sierra State Parks Foundation and the California State Parks give 30-minute tours daily in the summer, beginning the Saturday of Memorial Day Weekend and running through the end of September.

Smith has led hundreds if not thousands of the tours.

“I consider myself so fortunate that this all worked out,” Smith says. “The greatest joy I have had in life is to watch the expression on people’s faces as they go through the house—how much they appreciate this exceptional summer home and its magnificent setting.”

For more information or to arrange a specialized group tour of Vikingsholm, call 530-583-9911 or go to www.sierrastateparks.org.

Matthew Renda is a Santa Cruz–based writer.

No Comments