24 Feb Wyntoon: A Hidden Architectural Marvel

Located on the McCloud River north of Tahoe, the storied Wyntoon estate once owned by William Randolph Hearst and designed by Julia Morgan retains its secluded grandeur

On Valhalla Drive in Martis Camp—the lodestone of modern mountain architecture in the Truckee-Tahoe region—one can easily spot a little spur just off the road called Wyntoon Court.

For the uninitiated, it may seem strange that a truncated dead-end road boasting just a handful of the neighborhood’s sundry houses should bear a name that gestures to an obscure Native American tribe that once haunted the southern slope of Mount Shasta approximately 200 miles to the north.

But for the architecturally inclined, Wyntoon evokes something entirely different.

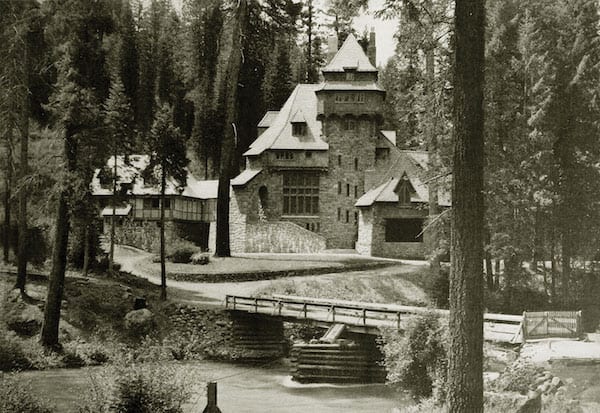

Phoebe Hearst’s Wyntoon designed by Bernard Maybeck pictured in 1906. The building burned down in 1929, courtesy photo

The towering Wyntoon structure featured a 75-foot-tall central tower built of stone, with six floors of rooms each accessed from landings along a main spiral staircase, courtesy photo

Wyntoon is the name of a sprawling private estate located in rural Siskiyou County in the northeastern stretch of California. It’s situated squarely on the bank of the McCloud River in the middle of two sharp bends, and it was once owned by the newspaper magnate William Randolph Hearst.

The fairytale-esque buildings commissioned by Hearst and designed by famed California architect Julia Morgan are widely regarded as an enduring architectural marvel, although one infinitely more secretive and remote than the celebrated Hearst Castle in San Simeon, another Hearst–Morgan collaboration.

While the castle at San Simeon functioned as Hearst’s primary residence and today is visited by more than 750,000 people annually, Wyntoon is more subdued than its coastal cousin.

Hearst envisioned Wyntoon as a summer retreat from San Simeon, safely cloistered in the alpine forest of Siskiyou County far from the throng and clamor of California’s bustling cities.

The estate retains its isolated quiet today, as it is closed to the public and only visible to intrepid kayakers and rafters able and bold enough to brave the McCloud River rapids.

Despite its relative isolation, the estate brims with Morgan’s characteristic structural ambition, her use of various disciplines, drawing on ancient Bavarian modes of building while containing flourishes of the Gothic Revival so in vogue at the time of its construction.

For this reason, Wyntoon is no less influential than many of Morgan’s works.

“I always liked the Teahouse on the McCloud at Wyntoon,” says Richard Loverde of Tahoe City–based Loverde Builders, Inc. “I did a takeoff of that building when I built the porte cochére for a building on Valhalla Drive.”

Loverde says he uses Morgan’s work at Wyntoon as a source of inspiration for certain designs and collaborations with architectural firms like Ward-Young Architecture & Planning in Truckee.

“I had a book of Morgan’s work,” Loverde says.

Morgan, who was the first woman to receive a degree from the architectural program at the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, designed more than 700 buildings throughout California. Included among her designs is the Twin Pines estate perched on the South Shore of Lake Tahoe, which now serves as a member retreat for the burgeoning Clear Creek Tahoe development, as well as Bow Bay on Tahoe’s southwest shore.

But it was Wyntoon that provided one of the most formidable challenges of Morgan’s career due to its remote location, the tumult of the times as the United States lurched into the beginning of the Great Depression right as construction began, and, most prominently, the fickle and difficult nature of her patron, William Randolph Hearst.

The Beginnings

William Randolph Hearst, photo by J.E. Purdy, courtesy Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division

Hollywood icon Clark Gable once sat on the banks of the McCloud River to listen to the babble of its bends while visiting Hearst at Wyntoon. Charles Lindbergh took in the scent of pine beneath the shade of the stately trees that dapple the estate. Joseph Kennedy visited the secluded wooded nave with his son John, who was just a boy at the time with presumably little inkling he would one day become the president of the United States.

Those luminaries were all guests of Hearst, the mercurial newspaper tycoon who built the largest media empire in the world during his heyday in the 1910s and 1920s, but also promoted a form of sensationalism called “yellow journalism” that many complain lingers in today’s media enterprises.

But long before Hearst, the grounds were home to the Wintun tribe, who hunted the hordes of spawning salmon that coursed through the McCloud every spring and autumn.

The area remained unsullied by European settlers until the 1880s, when Justin Sisson, a failed gold miner who repaired to the northern part of the state, bought the parcel along the McCloud and founded a fishing resort he called “Sisson’s-on-the-McCloud.”

At the time, Sisson was actively negotiating with the railroad to establish a line from Redding into Strawberry Valley, with hopes of attracting throngs of tourists to his various business enterprises, including an inn and a rowdy tavern.

After Sisson died in 1893, the property passed into the hands of Charles Wheeler, a notable San Francisco attorney who commissioned the construction of a large stone lodge, designed by San Francisco architect Willis Polk, to function as a headquarter for private hunting and fishing expeditions.

Wheeler rubbed elbows with the who’s who of the burgeoning California social scene at the dawn of the twentieth century, including a gold mine owner cum U.S. senator named George Hearst, who had recently made a splash by buying the San Francisco Examiner.

George Hearst was married to Phoebe Appleton Hearst, a Missouri native, suffragist and notable philanthropist who was often left alone with her only child, William Randolph, due to her husband’s requirements to attend to his various gold mining concerns and extensive sojourns in Washington D.C.

Phoebe Hearst, photo courtesy Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division

A friend of Wheeler, Phoebe Hearst accepted an invitation to visit his estate on the southern slope of Mount Shasta in the summer of 1900. Immediately enamored by the grounds and the surrounding area, she offered to buy it from Wheeler after spending a couple weeks there with her son. Wheeler initially balked, but Phoebe Hearst eventually prevailed upon Wheeler to give her a 100-year lease for the property.

In the meantime, Phoebe Hearst bought property upriver from the lodge and, ever the ambitious construction manager, commissioned the noted arts-and-crafts–style practitioner Bernard Maybeck to design a magnificent seven-story mansion after the fashion of a Rhine River castle.

The castle, with its aspirant gables stretching skyward from the forest floor, resembled the type of Black Forest fairytale castle one would expect to encounter in tales penned by the Grimm Brothers featuring Rapunzel, Hansel and Gretel or Sleeping Beauty. During the design phase, Maybeck enlisted a budding architect named Julia Morgan to assist.

After the castle was finished, Phoebe Hearst named the entire property Wyntoon, after the Wintun tribe, whose cultural productions adorned certain hallways and rooms throughout the castle.

The castle was considered an architectural marvel at the time as the Architectural Review dedicated a three-page spread to the building, praising in particular the Gothic dining hall, with its resonate stones that pitched steeply toward the building’s tall arches lending a spacious grandeur and “disheveled harmony” to the building and forested grounds.

By the time Phoebe Hearst moved into the castle in 1904, her son William Randolph Hearst had taken the inheritance of the Examiner from his father and built it into a full-blown media empire, with dailies in 30 major cities throughout the United States. His business was particularly brisk in California, where he employed the greatest writers of the day, including Ambrose Bierce, Jack London and Mark Twain.

As such, he had little free time, but did manage to spend portions of his summers at Wyntoon, where he was spending coin at a rapid pace in accumulating a considerable collection of European art.

The living room of Phoebe Hearst’s Wyntoon measured 36 feet high and consisted of steeply angled beams resting on 7-foot-thick stone walls. Tall fireplaces warmed each end of the medieval-styled room, courtesy photo

During this time, Phoebe Hearst often repaired to the mountain retreat with her many grandchildren, as William Randolph Hearst and his wife Millicent had five sons from 1904 through 1915. George Randolph Hearst, the eldest of the five children, was nearly washed down the McCloud River one summer, prompting his father to write to his grandmother that the boys required “a severe warning about the river.”

When Phoebe Hearst died in 1919 during the worldwide influenza epidemic, she willed the vast majority of her holdings to her son William Randolph, which included approximately $10 million worth of mining and industrial stocks and the family’s 270,000-acre ranch in San Simeon, an expansive fruit orchard in Butte County and the 900,000-acre Babicora Ranch in Mexico.

However, while William Randolph Hearst was to receive the estate’s extensive art collection, Phoebe left Wyntoon proper to her niece, Anne Apperson Flint, a posthumous move that caused her son no small amount of grief.

Refashioning the Estate

William Randolph Hearst was once close with his cousin, but after she and her husband moved into Wyntoon following Phoebe Hearst’s surprise bequeathment, she was met with nothing but enmity from the mogul.

When Flint loaned out artworks to an exhibition at the Palace of Fine Arts, Hearst confiscated them before they could be returned. Acrimony and harassment were such that Flint finally agreed to sell Wyntoon to William Randolph Hearst in 1925, washing her hands of the entire affair.

William Randolph Hearst’s elation at the acquisition was short-lived, as his mother’s architecturally famed castle burned to the ground in 1929, the fire starting in the kitching and consuming not only significant portions of the castle edifice, but a good fraction of precious artworks stored therein.

But Hearst wasn’t one to give in to despondency. At the time, Morgan, his preferred architect, was continuing work on the castle at San Simeon and putting the finishing touches on the Hacienda outside of King City, California. Despite these and many other projects, she expressed a willingness to design a new castle at Wyntoon that exceeded the former in structural splendor.

Julia Morgan at Wyntoon, photo courtesy Julia Morgan Papers and Sara Holmes Boutelle Papers, Special Collections and Archives, California Polytechnic State University

Morgan collaborated with Maybeck in the design of a 61-bedroom castle with two grand towers ascending from the front corners of the buildings with a profusion of turrets trickling down the arched roof lines on the long sides of the building.

In December 1930, Hearst bought the stones that once comprised a Spanish medieval monastery nestled in a river valley about 70 miles northeast of Madrid. The Santa Maria de Ovila Monastery had been standing since the twelfth century, but was razed in the early twentieth century as a result of a Spanish royal decree that decommissioned religious houses with fewer than 12 inhabitants.

When Hearst, who was a voracious collector of European bric-a-brac, got wind of the monastery’s imminent destruction, he paid $90,000 to have the grounds disassembled stone by stone and smuggled out of the country and transported into a warehouse in San Francisco with the intent of using the stones as the fundament for his grand new project. Part of the stones would be used to build an indoor pool. All told it cost about $1 million to get the broken-down monastery to San Francisco.

The only problem was that the year was 1930, and the stock market had crashed in October of the previous year. While Hearst was relatively insulated from the vagaries of the worst economic downturn in the history of the United States due to the recession-proof nature of his newspaper business, he was not exempt from it.

Hearst was also a spendthrift who earned millions of dollars annually and spent it as quickly as it came in, reserving most of his fortune for his penchant for grand construction projects, a trait he inherited from his mother.

So after Morgan submitted her plan for the castle that would’ve taken about $50 million to bring to fruition, Hearst scrapped it, trying to plug the leaks in his financial empire while still having enough money to finish San Simeon.

Instead, Hearst directed Morgan to build a fairytale village, with a series of more modest Bavarian houses half-timbered in the ancient style of Bavaria and Austria. To the degree that Morgan was chagrined by the about face, it couldn’t have lasted long, as she was soon dispatched on Hearst’s dime to Europe to study the style of architecture the magnate envisioned for his mountain retreat.

The Bear House is one of three homes at Wyntoon commissioned by William Randoph Hearst and designed by Julia Morgan, along with the Cinderella House and Fairy House, photo by Richard Barnes

In 1932, Morgan fashioned her master plan for the estate, which called for three houses—the Cinderella House, the Bear House and the Fairy House—built in a circular arrangement around an open green center with the backs of the houses built flush against the river’s swerve. Morgan emphasized whimsy in the design of the three-story houses, which featured steep gables and turrets all installed around the lush greenery of the lawn dotted with an elaborate fountain. Hearst also commissioned muralists to paint colorful scenes from Russian fables and the fairytales of the Brothers Grimm on the outside of the buildings.

Finally completed in 1933, the village was the focal point for Hearst’s ensuing recreational retreats until 1937, when the media magnate—beleaguered by the relentlessness of the Great Depression and incorrigible spending habits—declared bankruptcy.

After that, many of the artworks housed at Wyntoon were sold off, the operation of the property was put into the hands of a group of trustees called the Conservation Committee and Hearst had to pay rent out of his personal allowance any time he stayed at Wyntoon.

Also, several of the planned projects, including the Angel House, a complement to the original three houses, were halted. Construction on the Angel House was finally completed in the 1990s.

When World War II broke out in the early 1940s, Hearst fled San Simeon fearing an imminent Japanese invasion, not so far fetched given the attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, and repaired to Wyntoon with his actress girlfriend Marion Davies. It was Davies who attracted Hollywood’s leading lights of the day, including actor Clark Gable and directors Louis B. Mayer and Raoul Walsh.

Kayakers willing to brave the McCloud River can paddle through the waterfront backyard of Wyntoon, photo by Bill Tuthill

It was also during this time period, spanning 1942 to 1944, that Wyntoon played host to Joseph Kennedy Sr. Legend has it that Hearst was impressed with Kennedy’s son John, who braved the cold waters of the McCloud River for a brisk swim despite the wintertime temperatures that day.

Hearst would die only a few years later, in 1951, at his home in Beverly Hills. After that Wyntoon was managed by Hearst Corporation, which logged several hundred acres of the adjoining properties and the old Wheeler Ranch for about a $2 million annual return.

Today Wyntoon is managed by the Hearst Corporation as a private retreat. Unlike the castle at San Simeon, the general public is not allowed on the property. But for the intrepid few, a 7-plus-mile kayak trip from the Lower Falls to the Upper McCloud Reservoir yields spectacular views of the property among the towering conifers and whimsical buildings that still pay testament to the marvelous lives, careers, works and interlacing destinies of Julia Morgan and William Randolph Hearst.

After researching Wyntoon, Santa Cruz–based writer Matthew Renda wishes he were an expert kayaker so he could catch a glimpse of the property in person.

Debra Green

Posted at 14:34h, 17 JulyMy great grandfather was one of the builders of the castle that burned. He was a mason and was hired by William Sr. to build the grand fireplace. We have photos of the project. Gifts from William Sr. My grandmother always said there was another castle that had burned before the last castle burned down.

Tahoe Quarterly

Posted at 20:14h, 17 JulyWow! Very cool. Thanks for sharing, Debra.

Julene Hunter

Posted at 23:46h, 21 AugustThanks for the fun article. Lil’ correction: Phoebe Hearst was not a suffragette. That is a derogatory term, and would be used if you thought a woman’s right to vote was “silly.” To her contemporaries she would have been a suffragist.

Tahoe Quarterly

Posted at 07:46h, 22 AugustThanks for the note, Julene. Research supports your point, and we have made the correction.

Nancy Hurley-Madison

Posted at 17:09h, 03 JanuaryI would Love to see the photos you have of the castle your grandfather helped build!

Nancy Hurley-Madison

Posted at 17:12h, 03 JanuaryDebra, I would love to see photos of the work your grandfather did on the original castle!

Linda English

Posted at 12:59h, 04 FebruaryLove this article. Who knew??? Visited Hearst Castle on the central coast but never realized this beauty was in my “backyard” now. Thank you for sharing this!

April Reinhardt

Posted at 19:49h, 03 MarchMy mother lived in McCloud as a child in the 1940’s as my Grandfather worked at the logging camp. She remembered that periodically Hearst would send cars into town to pick up the children to come swim in their pool at Wyntoon. She remembered getting to go and as a young girl and asking Marion Davies if she could have one of her cigarettes to take to her father. Once the saw mill starting having financial troubles they moved back to Missouri where my grandfather was originally from. She always shared her stories as a child swimming in the pool at Wyntoon and drinking water from the spring at Mt. Shasta.

April Reinhardt

Posted at 20:26h, 03 MarchCorrection, I’m not aware if there was an indoor pool but my mother was picked up in a limousine at the McCloud company store as a child to go to parties at Wyntoon.

Marie dreyerDr

Posted at 13:51h, 04 MarchI know what happened to the monastery stones. While still in crates packed with excelsior and that were marked with information for reconstruction, there was a fire. After that all the stones were dumped and hidden next to the Japanese gardens in San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park. Hearst had given the Monestery to the city as a gift. He suggested they rebuild it in the park or somewhere suitable. This was before the fire. Some think the fire was arson, because the idea of rebuilding was to costly. As a child I wondered about the carved stone blocks in a giant pile. Later I researched the Examiner Morgue. Today, many of the stones have been repurposed in the gardens of the Arboretum and gardens.

Ken McPherson

Posted at 14:26h, 16 MarchActually, the remainder of the stones were given several years ago to the Abby of New Clairvieu located in Vina California where they have been reconstructing the chapel. The order of monks there are descendants of the order that originally built it. It has been like building a three dimensional jigsaw puzzle without a picture. Whereas the stones were originally numbered and a plan made for reconstruction, the fire and then the elements, over time obliterated the markings. Missing pieces have had to be recreated. They’ve done a marvelous job.

Patrice Moore

Posted at 04:16h, 03 AprilMy mother and aunt lived in Mc Cloud as children. Both my aunt and uncle worked at Wyntoon for several years. I was fortunate to visit all of the properties. Something I will never forget!

LaDeane Allen

Posted at 17:50h, 08 JulyOur family lore tells of my great grandfather and my grandfather helping to build the original Wyntoon building. Also, we were told that a lock of my great aunt, Hazel’s, hair was placed in the corner stone.

Jim Gray

Posted at 18:53h, 15 JulyIn the summer of ’82 my older brother, myself and two others rode inner tubes down from Fowlers on the McCloud River. The water was ice cold and we were not wearing life jackets. We ended up at The Bend and climbed up over the retaining rock wall and we were next to the Storybook Castle. The caretaker, Don Winston, found us wandering about and gave us a ride to the reservoir.

Marilyn Ponci

Posted at 13:14h, 16 SeptemberThe monastery stone ended up in Vina, on the former “Great Stanford. Ranch” near red Bluff, Ca.. The ranch is owned by a group of. Monks, who farm it, have a very famous wine they make and sell, and practice their religion. They acquired the stones from San Francisco and hired a stone worker from Spain to cut the old stones and rebuild the monastery as it was in Spain. It took years, but now is open to the public and has regular posted mass each week. Worth a visit to see the ranch, church, and for wine tasting..

michael simi

Posted at 13:18h, 03 JanuaryI am of Italian heritage. Many of my family immigrated to McCloud to work in the lumber mill. In the summer of the 1950s and 60s we would travel to McCloud to visit cousins. The order of the day was baseball among the Italian families in McCloud, kids only trout fishing at Huckleberry Creek, watching the bears scavenge at McCloud’s town dump, and exploring grounds at Wyntoon.

Carol Shockley

Posted at 15:54h, 23 Aprillooking for updated info on this beautiful home. and it’s outside homes as well. bear house, fairy house, Cinderella house, angel house, etc. is there a current caretaker there today ?