24 Feb Don’t Count Out the Bristlecone

As the world’s longest-living tree faces new perils in a warming climate, scientists remain cautiously optimistic that this gritty species will endure

Hard to comprehend how many stunning sunsets, torrential blizzards and cold, windy nights a Great Basin bristlecone pine tree sees in its lifetime. These remarkable trees, found only on high mountain ridges in Utah, Nevada and eastern California, are some of the longest-living organisms on earth, surviving for nearly 5,000 years.

Two bristlecone pines maintain their stoic stance even after death. With little threat from wildfire, dense and twisted bristlecone trunks often stay upright for centuries after the tree has perished, photo by Brian Smithers

To endure in such an unforgiving alpine environment makes the Great Basin bristlecone a true wonder of the natural world and reflects the species’ uncanny resilience and unique adaptations to the high-desert ecosystem. Somehow, some way, the bristlecone thrives where most other tree species could never survive.

“They are the grittiest of all tree species,” says Brian Smithers, a research professor at Montana State University who studies bristlecones and other high-elevation plant species. “They have this amazing ability to handle the worst that nature can throw at them.”

While Smithers is a believer in the bristlecone’s unmatched hardiness, he’s also on the leading edge of research about how climate change might affect the tree’s future. Recent studies and field observations indicate that previously unseen environmental factors like fire, insects and competition for new habitat are impacting the success of bristlecones in some locations.

How much these factors will impact the bristlecone’s survival as a species is the big question. Are we seeing the beginning of the end of the world’s oldest trees? The expert consensus is no. But ultimately, like all the proposed potential effects of climate change on our planet, the future of the bristlecone is uncertain.

The Toughest Fighters in Town

What allows a Great Basin bristlecone to persevere for such an unfathomably long lifetime has piqued the interest of scientists since the 1950s, when University of Arizona dendrochronologist Edward Schulman identified 20 trees that were over 4,000 years old in a grove in the White Mountains outside the town of Bishop, California. Within that grove, now known as the Ancient Bristlecone Pine Forest, Schulman also identified what is thought to be one of the oldest living bristlecones, a tree he named Methuselah that he dated to 4,854 years old.

The secret to Methuselah’s old age is that the bristlecone’s incredibly slow growth rate makes the wood extremely dense and resinous, which helps the tree resist insects, rot and erosion. Bristlecones also prefer rocky dolomite soils where most other vegetation cannot grow. The lack of vegetation helps reduce fire danger as the isolated trees are often perched on rock outcroppings with no surrounding surface fuels.

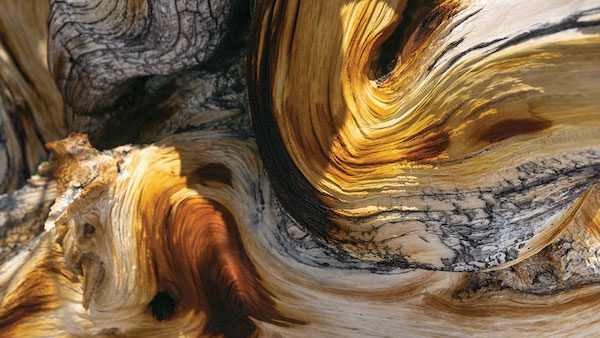

By growing slowly, bristlecones form extremely dense and resinous wood that is rot- and insect-resistant, photo by Seth Lightcap

The twisted and seemingly half-dead trunks associated with bristlecones are the result of a trait called sectored architecture. This means each tree root only feeds the part of the tree directly above it. So if a root dies, only the tree section that’s directly connected to that root dies. This trait allows the bristlecone to draw all available water and nutrients to a small percentage of the tree during drought periods. The dead, sculpted trunks are sections the trees let die to save itself in the long term.

Another advantageous trait of bristlecones is they produce viable and genetically diverse seeds their entire lives. Connie Millar, a scientist emerita with the U.S. Forest Service Pacific Southwest Research Station, says this regeneration strategy is crucial to both the bristlecone’s past and future success.

“By scattering lots and lots of highly genetically diverse seeds on the landscape every year, it’s almost like an experiment by each tree,” says Millar. “The seeds may be way differently adapted than their moms and dads, so if the environment is changing, it’s the seeds that are best adapted to the current conditions that will persist.”

Losing Ground to Limber Pine

Millar and Smithers published the results of a 2017 study that was one of the first to detail how Great Basin bristlecones were faring in a warming climate. Their study examined how quickly bristlecones were establishing new individuals in previously above-tree-line terrain that had only recently become warm enough to sustain vegetation. The bristlecone’s only competition for habitat in these new areas was from the limber pine, another long-lived, high-elevation species that can survive up to 2,000 years in the right conditions.

A half dead, half alive bristlecone pine in Nevada’s Great Basin National Park, photo by Seth Lightcap

They found that the limber pine has taken the early lead in colonizing newly available habitat because it’s more adaptable to different soil types and has a more advantageous seed dispersal method than the bristlecone.

Bristlecone seeds are lightweight, winged and get dispersed by the wind, falling wherever they may. As most seeds fall on arid and desiccating soil, the survival rate for bristlecone seeds is less than 1 percent. Limber pine seeds, on the other hand, are large, unwinged and almost exclusively dispersed by the Clark’s nutcracker, a high-elevation bird. The nutcracker eats some of the seeds it collects but buries thousands more in hidden caches that it returns to in the winter. But the nutcracker doesn’t eat all that it buries, which effectively plants the limber pine’s seeds.

“To have someone out there planting your seeds in these environments is a great leg up,” says Millar. “Even though the bristlecone produces more seeds, limber pine has the early advantage because of its relationship with Clark’s nutcracker.”

Smithers explains further.

“In a situation where climate is not changing, this is not a particularly good adaptation for the limber pine to expand its range because if the bird stashes the seed in a spot that is not a good spot or too far upslope, it would just die,” he says. “But now that the climate has warmed, and the snowpack is lower, those seeds that are being cached above tree line by the nutcracker have a better chance of germinating and establishing, so the limber pine is moving uphill faster than the bristlecone is.”

Both Millar and Smithers are quick to defend the future potential of the bristlecone in these new habitats, however, noting that the limber pine may be performing well now, but all it would take is an environmental factor like mountain pine beetle, which limber pines are highly susceptible to, to erase all the ground the species has gained on the bristlecone.

The Perilous Potential of Pine Beetles

In July 2019, Millar was hiking on Telescope Peak in Death Valley National Park when she came across a sight she hoped she would never see: Thousands of bristlecones near the summit had been killed by what appeared to be a mountain pine beetle attack.

These tiny beetles have already had a devastating impact on forests in all 19 western states and Canada, destroying nearly 100 million acres of timber during drought years starting in 2004. Most pine species are susceptible to attack by the beetle, which bore into the wood of healthy trees to lay their eggs. The larvae then chew through the tree’s phloem to gain energy and grow before pupating, changing into adults and then boring out to go infect other trees. As the larvae eat the phloem, the flow of nutrients and sugars to the roots gets cut off and the tree dies.

The incident on Telescope Peak surprised Millar because there was no recorded evidence of beetles attacking

The incident on Telescope Peak surprised Millar because there was no recorded evidence of beetles attacking

Great Basin bristlecones. Up to that point it was thought that the bristlecone’s dense wood and toxic resins were an impervious defense against beetle attacks.

“I was shocked to see the extent of the bristlecone mortality on Telescope Peak,” says Millar. “It was really disheartening given what it meant for the species in general, and the future of this stand, which is one of the southernmost populations of bristlecone.”

The news quickly made its way to Barbara Bentz, a research entomologist at the Rocky Mountain Research Station. Bentz was surprised as well. She had published a paper in 2017 detailing the toxic resins that were likely the bristlecone’s primary defense against beetles, and field observations noting that beetle attacks had yet to affect Great Basin bristlecones.

Bentz and colleagues visited the decimated Telescope Peak stand soon after Millar and came to a conclusion about what happened.

“The bristlecone on Telescope Peak grow in close proximity to limber pine, which is highly susceptible to pine beetles,” says Bentz. “We think warm drought conditions between 2014 and 2019 caused a severe beetle outbreak in the limber pine that then spilled over into the bristlecone.”

The second surprising twist to Bentz’s findings was that the beetles had paid the ultimate price for attacking and killing the bristlecones.

“What was very interesting was that in the trees that had been attacked, the beetle larvae died before they could develop to the adult life stage and emerge,” says Bentz. “This confirmed our lab studies that there is indeed something about bristlecone that is killing the beetle offspring, and that it would be fairly unlikely to have an outbreak in a stand that is only bristlecone because the beetles can’t complete their life cycle.”

A Mere Hiccup in Bristlecone History

Faced with the potential of being outcompeted for new habitat, and taken out by hosted pine beetle attacks, there’s no doubt some uncertainty in the Great Basin bristlecone’s future. But Millar, Smithers and Bentz do not believe these environmental factors mark the ultimate demise of these ancient trees. All three experts think these newly arisen threats might extirpate some marginal populations, but they will ultimately be taken in stride by the proven persistence of the species.

U.S. Forest Service scientist emerita Connie Millar stands next to a massive bristlecone in the White Mountains of eastern California, photo courtesy Connie Millar

“I certainly don’t think the bristlecone are doomed,” says Smithers. “They’re really tough. They’re going to be OK. But I am concerned for specific populations for sure.”

The trees Smithers is concerned about are at the lower elevation of the bristlecone’s range. This includes Methuselah at 10,000 feet in the White Mountains, where bristlecones are found between 10,000 and 12,000 feet.

Millar echoes these sentiments, and believes the bristlecone will overcome the climatic changes of the modern era, as they are not its first rodeo.

“This is a native species that has evolved in periods of great warmth,” says Millar, pointing out that bristlecones survived the warm and dry middle Holocene period between about 4,000 and 7,000 years ago. “They persisted through that, so I remain optimistic that the species has the capacity to endure these changes. We will likely have to tolerate seeing some marginal stands decline, but I have little doubt that the species as a whole will be triumphant.”

Seth Lightcap is an Olympic Valley-based writer, photographer and avid explorer of Sierra rock, snow and trail. See more of his stories at sethlightcap.com.

No Comments