22 Feb The (Artificial) Grass Isn’t Always Greener

While the benefits of synthetic turf over real grass seem clear-cut, the science is surprising and mixed

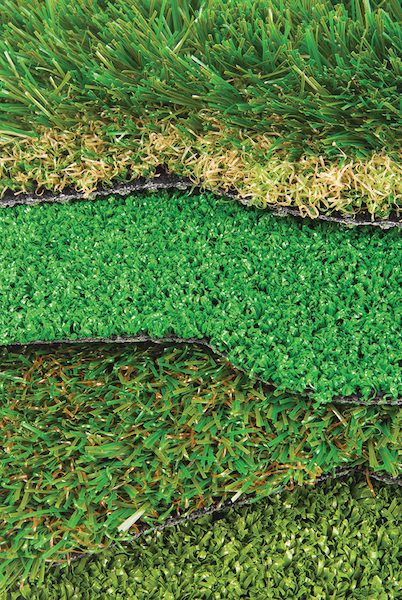

Artificial turf varies greatly in appearance and quality, with new products designed to look like real grass, iStock photo

As the Tahoe Basin and much of the American West have weathered protracted periods of drought in recent decades, artificial lawns have been touted as a potential means of reducing water consumption.

Water officials and conservationists have an increasingly dim view of the immaculately green lawn, contending the use of a scarce resource to keep the yard in fine fettle is superfluous.

“We all have a shared responsibility to continue to limit non-essential outdoor water use while the state grapples with extreme weather,” Joaquin Esquivel, chair of California’s State Water Resources Control Board, said in June 2023 when announcing the ban on drinking water for non-essential outdoor use on government and business properties.

Unlike some of the most drought-affected Western locations like Southern California or Las Vegas, the Lake Tahoe Basin enjoys an abundance of water, collecting it from mountain streams, aquifers and in some cases the lake itself. Nevertheless, Tahoe residents are increasingly opting for artificial lawns.

“Every year we are installing more artificial turf around Lake Tahoe. It just seems to keep growing in popularity,” says Brian Connors, owner of Truckee-based Peak Landscape. “Some seasons we even do more artificial turf than regular.”

Demand for faux grass is especially high among lakefront properties, Connors adds. “You don’t have to thatch it or aerate it or fertilize it. We aren’t using chemicals for weeds or worried about fertilizer runoff or using gas to mow the faux lawn, because it doesn’t need these things.”

Emerging Science

However, as the scientific analysis of artificial turf’s impact on ecosystems, particularly ones as sensitive as the Lake Tahoe Basin, continues to emerge, some argue the environmental benefits are not so clear-cut. The Tahoe Regional Planning Agency (TRPA) considers faux lawns land coverage, the same as driveways or decks, and requires homeowners to obtain a permit.

Jeff Cowen, public information officer for the TRPA, says the agency is aware of the water conservation argument for synthetic grass, but that it is only one factor in a much broader ecological calculation.

“We recognize how artificial turf benefits water consumption, fertilizer use and other issues, but there are other ways to achieve those benefits,” Cowen says, explaining that there are significant ecological costs to the replacement of native vegetation. “Artificial turf replaces the natural processes of the soil. You can take it all the way down to soil bacteria like mycorrhizae, the root structure that stabilizes soils and prevents erosion—it replaces all of those things.”

Soil health isn’t the only factor, as scientific studies have only just begun to emerge that weigh the pros and cons of artificial grass.

In 2021, Leslie Golden of the Center for Computational Astrophysics found that “the substitution of artificial grass for natural grass contributes to global warming.” This is because faux grass gets hotter in the sun than real vegetation, which not only remains cool but also sequesters carbon through photosynthesis.

A study published by the University of New Mexico in 2020 found that, as it relates to athletic fields, water savings ostensibly provided by synthetic turf never materialized because it had to be frequently watered to keep it cool enough for safe use. However, the authors acknowledge this deficit in water savings is perhaps unique to the climate of the American Southwest, with its consistently high temperatures and sunny days.

Ball Fields in the Tahoe Basin

At Lake Tahoe, several athletic fields use artificial turf, including at Lake Tahoe Community College on the South Shore and North Tahoe Regional Park in Tahoe Vista.

Field 4 at North Tahoe Regional Park uses a third-generation artificial turf that allows for year-round use. The North Tahoe Public Utility District, which manages the park, placed a curb around the field to ensure runoff does not pollute Lake Tahoe, photo courtesy NTPUD

“The heat is not really as much of a problem in Lake Tahoe, where summer temperatures usually stay in the 70s and 80s,” says Jeremy Evans, women’s soccer coach at Lake Tahoe Community College. “In our climate, natural grass is really difficult to maintain because we have a short growing season and it doesn’t get that warm. Plus, sun angles are always kind of funky because of the trees.”

Amanda Oberacker, recreation, parks and facilities manager for the North Tahoe Public Utility District, agrees that artificial grass makes sense for athletic fields in the Tahoe Basin. Along with the substantial water savings, the surface allows the utility district to conduct snow removal during the winter, giving residents year-round access to a top-notch field at North Tahoe Regional Park.

“We’re giving people the opportunity to play on athletic fields they normally wouldn’t have due to weather,” Oberacker says.

She adds that natural grass fields would not be able to sustain the amount of wear and tear due to the high intensity of usage. A recent study commissioned by the city of Zurich in Switzerland bolsters Oberacker’s assertion, finding that natural grass fields have the lowest overall environmental footprint, but only if use remains low, as the need to constantly replace natural grass eliminates its narrow environmental advantage.

Too Hot for Homeowners?

The calculation is different for homeowners. The heat problems highlighted in the University of New Mexico study can afflict properties in the Tahoe region that have significant exposure to sunlight, says Connors, who once installed faux grass at a house at the foot of Alpine Meadows that did not fare well.

“The home was at an elevation of 7,000 feet, and they had direct sunlight that was reflecting off the home’s windows. And all that sunlight actually melted the turf,” Connors says. “There were lines across it where the turf had actually melted from the intense sun.”

Connors says homeowners must realize they have to water the surface before letting children and pets play on it.

“Regular grass is cool to the touch on a hot summer day. Artificial is hot to the touch and can increase the surrounding temperature, similar to how concrete or asphalt might,” he says. “I tell clients to run the irrigation for five or 10 minutes before letting kids play on it if the artificial grass is in direct sun and it’s hot out.”

Heidi Kratsch, professor and sustainable horticulture specialist at the University of Nevada, Reno, says homeowners should be wary of contributing to a local warming effect by installing systems less adept at absorbing heat.

“Real plants have internal cooling systems. Faux turf doesn’t,” she says. “The temperatures of faux grass have been recorded at 120 to 180 degrees Fahrenheit. I think the most important point I would like to make is that, especially here in the West, where our cities are getting extremely hot—our temperatures are getting hotter every summer—the last thing we want to do is have more unplanted areas.”

The TRPA’s regulatory approach recognizes the difference between artificial turf at the homeowner level and institutions that provide recreation opportunities to the community.

“We’ve tried to be creative, so that large institutions, public institutions, public fields, can use artificial turf because of how much water is saved and how much fertilizer use is reduced, because we do want to reduce the use of phosphorus-based fertilizer,” Cowen says. He adds that the overall footprint of athletic fields in the Tahoe Basin is negligible, particularly when considering the inherent recreational benefits.

Health Concerns

Nevertheless, there is a contingent of artificial grass critics whose major contention is not ecological, but tied to deleterious effects on human health. In short, the argument is that synthetic turf contains high levels of chemicals found in plastics like PFAs, also known as “forever chemicals.”

In 2023, California Governor Gavin Newsom signed legislation that allowed local municipalities to ban synthetic grass, citing concerns about adverse health effects. The science regarding faux turf’s impacts to human health, including its potential as a carcinogen, is still emergent, complex, ambiguous and sometimes contradictory—much like the environmental science.

But before delving into a meta-analysis, it is important to clarify that the artificial grass currently employed in neighborhoods and athletic fields is significantly different than the original surface introduced to the world in the 1960s.

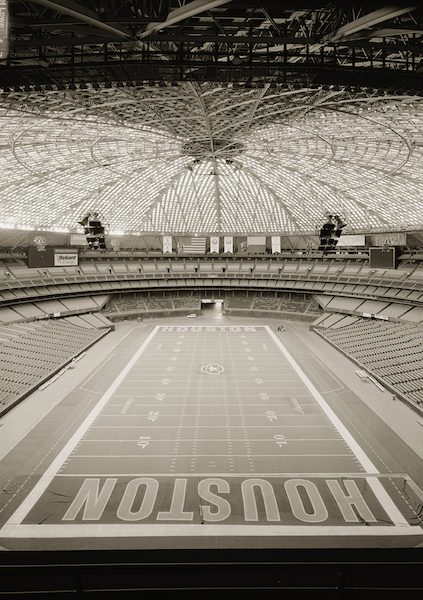

The interior of the Houston Astrodome in 2004, photo courtesy Library of Congress

The Birth of Artificial Turf

When the Houston Astrodome opened in the mid-1960s, it was touted as the Eighth Wonder of the World. It was, in fact, the world’s first multi-purpose domed stadium and became the model for domes that would follow in New Orleans, Detroit and Minneapolis.

The Astrodome was built by Roy Hofheinz, a former state judge who went on to become owner of the Houston Astros. The problem when the team moved into their new stadium in 1965, aside from the Astros’ putrid play that year, was the natural grass field kept dying, mostly because the roof was painted a nonreflective color to fix the problem of players routinely missing fly balls due to the glare.

In stepped James Faria and Robert Wright, engineers at the Monsanto Company, who invented what they dubbed ChemGrass, which was rebranded as AstroTurf after the team became the first to install an artificial grass surface in 1966.

Increasingly, baseball and football franchises realized AstroTurf had advantages as it related to maintenance, fertilizer costs and water consumption, and the playing surface became more widespread, with the Cincinnati Reds, Philadelphia Phillies, Toronto Blue Jays and Kansas City Royals all switching from natural grass to AstroTurf.

Although the Houston Oilers also played in the Astrodome, in 1969 the Philadelphia Eagles became the first team with a stadium used exclusively for football to install the playing surface. Several other teams followed in ensuing years.

Search for a Safer Surface

But as early as 1971, safety and health concerns began to emerge, with a Congressional committee investigating whether the surface was responsible for an increase in player injuries. It’s a controversy that rages to this day, even though artificial turf has undergone several iterations focused on improving safety.

A study commissioned by the NFL and published in the American Journal of Sports Medicine in 2009 found that knee sprains occurred at a 22 percent higher rate on artificial surfaces than on natural grass, and that ACL tears occurred at a 67 percent higher rate between 2000 and 2009. Turf toe, a serious injury for athletes (it led to the retirement of Deion Sanders, for instance), is believed to be caused by the more rigid nature of the surface than real grass.

To fix this problem, artificial turf engineers began using materials such as sand—known as infill—as early as the 1970s, which ushered in the second generation of the product. The second generation also employed longer fibers to provide a more natural grass feel. The refinements continued into the 1990s, when smaller rubber granules were incorporated into the playing surface.

The third generation of artificial turf, introduced in the 2000s, mixed technological advancements in synthetic fibers with various infills, including recycled rubber, coconut husks and cork. The athletic fields at Lake Tahoe Community College and North Tahoe Regional Park—along with an estimated 12,000 high school, collegiate and professional fields across the country—use third-generation turfs with long fibers replete with infill.

Despite the innovations, athletes still claim that artificial turf causes more injuries. In 2015, players from various national soccer teams complained about having to play the 2015 FIFA Women’s World Cup entirely on artificial surfaces. In 2022, after San Francisco 49ers defensive end Nick Bosa tore his ACL while playing on the new FieldTurf at the Meadowlands in New Jersey, he started a petition calling for the NFL to ban the surface.

“My number one preferred surface is always grass,” Evans says. “To me, soccer is supposed to be played on grass, but I think there are benefits to turf, at least up in our climate.”

Health concerns extended beyond the kinesiological into the realm of overall health in 2023 when the families of six former players for the Philadelphia Phillies, who all died of a rare form of brain cancer before the age of 60, attributed their premature deaths to prolonged exposure to PFAs found in high levels in AstroTurf.

The hypothesis suffers from a dearth of scientific evidence, however. One study conducted by Rutgers University found that crumb rubber used in synthetic fields in New York City contained elevated levels of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, which have been linked to certain cancers. But the researchers warned the results could have been affected by the solvent used to extract the chemicals from the rubber.

In 2020, the journal Science of the Total Environment published a study that analyzed the potential health impacts of exposure to recycled rubber infill and concluded that no health concerns could be identified.

In the United States, the EPA released preliminary findings of its 2019 investigation and found: “In general, the findings from the report support the premise that while chemicals are present as expected in the tire crumb rubber, human exposure appears to be limited based on what is released into the air or simulated biological fluids.” The agency has pledged to conduct further studies.

Given the conflicting evidence, some institutions have opted for infill made of coconut fibers, cork or sand out of caution.

For instance, Lake Tahoe Community College uses a mix of cork, coconut and natural binders as its infill. The North Tahoe PUD uses rubber granules, noting that the benefits of proper drainage drive the decision. The utility district has a curb around the field to ensure runoff does not contribute to microplastic pollution into Lake Tahoe.

Cost of Quality

Oberacker from the North Tahoe PUD notes the cost-benefit analysis is different for a homeowner looking to have a lawn.

“If you are installing an artificial lawn just because it’s nice to look at, it might be a better option to go with some dryscape options that are more symbiotic with our climate,” she says.

The original artificial turf on Field 4 at North Tahoe Regional Park was installed in 2007 and lasted until 2022, photo courtesy NTPUD

Homeowners must also confront the large discrepancies in price and quality in the market.

“The quality is very good to very poor,” says Brad Kurtz, a sales representative with Reno’s Western Turf & Hardscapes.

The company uses material supplied by Global Syn-Turf, which carries a warranty against defects, fading and other problems that afflict low-quality synthetic turf.

“In general, I would warn against buying products from a company that isn’t willing to provide warranty against defects and fading,” he says.

Inferior products, some of which are available for as low as $1 per square foot on the Internet, have problems such as chemical leakages and off-gassing—the odor that emanates from plastic products, particularly when new.

“It’s normal for polymer products to do that when they are new—think of the new car smell—but it is not normal for these products to keep doing it,” Kurtz says. “That’s where quality comes in.”

Homeowners can expect to pay between $3 and $5 per square foot for synthetic turf, Kurtz says, noting that athletic fields require a more specialized surface, which drives the price up to as much as $7 per square foot.

Kratsch, the UNR professor, says homeowners are better off thinking of artificial turf as a replacement for rock than grass, given that it fails to facilitate the natural organic processes of real vegetation.

“It’s basically a hardscape material,” Kratsch says. “It shouldn’t be thought of as an alternative to a plant. If a plant can’t work there, then, OK, maybe consider this material.”

Matthew Renda is a Santa Cruz-based writer and former Tahoe resident. Michelle Mastro is a freelance writer covering home, travel and culture. She lives in Indianapolis but was born and raised in California. Her parents were married at Lake Tahoe.

No Comments