22 Feb Where Good Things Grow

Born and raised in the Russian Far East, Anya Dublennikova turned her lifelong love for plants into a thriving Truckee business

In addition to repotting and consultation services, Good Anya sells a wide assortment of plants, including select tropical varieties, photo by Ryan Salm

On a morning when Truckee is blanketed in snow, the inside of Good Anya Plant Shop is lush and inviting, a multitude of well-loved plants radiating their positive energy onto anyone who walks through the door.

The owner of Good Anya, Anya Dublennikova, unlocks the door and we get cozy on a vibrant green couch among fun throw pillows. She drops a bag of Yogi immune-support tea in a thick clear cup that she keeps in an intricately patterned metal stand.

“This glass was invented by a Russian woman, and I heard that NASA astronauts took it into space because it was designed to not roll off the table. That’s why they give these to you on trains,” Dublennikova says, tapping on the side to show its durability.

Warming up with the tea, Dublennikova shares her story: How she grew up on the banks of the Amur River in the Russian Far East. How she loved working with plants in her family’s rural “dachas,” where they grew vegetables because they weren’t available anywhere else. How she discovered a better life while traveling with her college band. And how she eventually made her way to San Francisco, then Truckee, where she parlayed her affinity for plants and art into a burgeoning career as a business owner and artist.

Much like the vibrant green plants that adorn her shop—from common, “hard-to-kill” staples to “pet-friendly” options to tropical varieties not easily found around Tahoe—Dublennikova injects life into the space while imparting a welcoming vibe that resonates with all who cross her path.

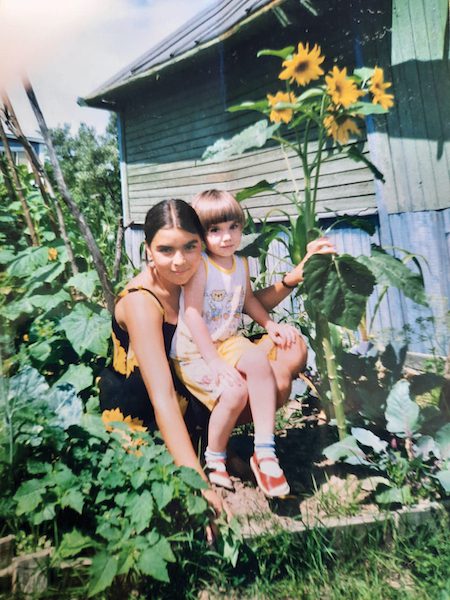

Dublennikova and her sister on their family’s dacha in 2003, courtesy photo

Siberian Roots

Dublennikova, 36, grew up in Khabarovsk, about 5,000 miles from Moscow and just a stone’s throw from China, which is visible on the other side of the Amur River. Because most people have never heard of Khabarovsk—and can’t pronounce its name—Dublennikova finds it easier to simply say she’s from Siberia.

About 600,000 people live in Khabarovsk, but comparing the city to Moscow is like comparing San Francisco to New York, says Dublennikova, adding that, while her hometown may appear to be near the Sea of Japan on a map, “going to see the sea” would be like a Tahoe resident going to Mexico. It’s a bit of a drive.

The Amur is one of the longest rivers in the world, home to more than 100 species of fish in just the lower portion alone, as well as close to 400 species of birds, 70 types of mammals, including the near-extinct Amur tiger, and some 5,000 species of vascular plants.

“There are not so many mountains, but lots of forest,” Dublennikova says.

Dublennikova’s grandmother has long resided near the shores of Russia’s Lake Baikal, the oldest and deepest lake in the world at 5,315 feet. That’s more than three times the depth of Lake Tahoe, which happens to be Baikal’s sister lake—a fact Dublennikova learned from a “Keep Tahoe Blue” bumper sticker written in Russian.

Farther east, Dublennikova’s father grew up on Russia’s Kamchatka Peninsula, which also has a “natural wonders of the world” feel. Located between the Bering Sea and the Sea of Okhotsk, the rugged region is known for its active volcanoes, big-mountain skiing and snowboarding, and abundance of flora and fauna.

“It was wild … my dad was telling me that there were so many fish in the sea one year that they were catching them with their bare hands,” Dublennikova says, explaining that caviar was in such abundance that its residents mixed it with their mashed potatoes in place of butter.

Both sides of Dublennikova’s family had a “dacha,” a seasonal cottage in the countryside where residents grow food. Dublennikova’s grandparents on her father’s side had a dacha near her home in Khabarovsk, and she worked there every summer.

Dublennikova visits her grandmother at her dacha in Siberia in 2023, courtesy photo

“I remember going there as a kid … everyone had to work, and we had to grow our own vegetables because they weren’t available any other way,” Dublennikova says. “When the USSR fell apart, there was no food. We were given tickets to wait in line for bread and other things. I would wait in line while my mom would go wait in other lines because when they ran out, they were out.”

Some days, things like bread or eggs just weren’t available.

“I have to remind myself of those days to be grateful for what I have here,” Dublennikova says. “We have everything we need here, all the time, and it wasn’t like that for me growing up. The whole ’90s, we were very poor. There were a lot of mafias, and everything was government-controlled. Because I was a kid, it didn’t seem that scary, but my parents told me it was a tough time.”

Since they did not own a car, they traveled by bus to their family’s dachas, where Dublennikova fondly remembers running around in the garden planting seeds.

“It was tedious planting them, but I’d like the tedious jobs, and I’d be singing songs calling for the rain,” says Dublennikova, who also enjoyed helping her mother care for flowers and houseplants in their small apartment back in Khabarovsk.

The family would travel three days by train to visit her grandmother near Lake Baikal. When not working in the dacha, Dublennikova and her grandmother would venture out into the taiga and hunt for mushrooms, berries and fern sprouts. To this day, she says, the smell of warm, wet pine needles takes her back to that place.

“I loved this one pine tree. I would wrap my arms around it and tell my grandma, ‘This tree is singing,’” Dublennikova says.

Branching Out

Dublennikova sang in a traditional Russian folklore band as a child and later formed a band with some of her friends from her college, Far Eastern State Transport University.

Their band, Istok—meaning “the root of something, like the beginning of a river”—won a music competition that resulted in a trip to Spain. There, Dublennikova was impressed with how clean, pretty and put together everything was.

“It was warm, and the ocean was right there. I got a taste of better living,” Dublennikova says.

She had also been to the United States when she was 10, visiting Khabarovsk’s sister city of Portland, Oregon, with her folklore choir in a cultural exchange program.

“It was my first time in a mall, and I remember the bathroom smelled good,” she says. “There were glass doors that weren’t broken or destroyed. People wore their shoes indoors.”

Before her college band broke up, two of her bandmates moved to the U.S. and another went to London. One of them landed in San Francisco and, after having a baby, convinced Dublennikova to come out and help. She got a tourist visa in 2012 before applying for a green card, which she received on her second attempt in 2014.

Dublennikova enjoyed San Francisco because it reminded her of Europe—a melting pot of different cultures.

“I didn’t know many people and I barely spoke English. But I was in love with San Francisco and the endless opportunities that America stands for,” she says. “Plants became my roommates and my friends.”

Dublennikova got back into singing and painting—another childhood hobby—and taught a children’s art class every Saturday. She studied graphic design at San Francisco Community College, worked a couple of hospitality and retail jobs and joined the production team at Water Lily Pond Floral Design Studio.

But while she was mesmerized by the city, she also saw the dark side of rampant drug use and homelessness.

“I loved it, but I didn’t see myself raising kids there,” she says. “That’s not good when something like that becomes normalized … we didn’t really have that in Russia.”

And although she felt sorry for the homeless, how could she give them money when she was a freshly relocated immigrant in a city where she could barely pay rent?

“You have to have empathy for everyone, but I was in San Francisco for five years and I thought, ‘How is my life better now?’” she says.

Anya Dublennikova sells her moss wall art during a pop-up event at Muse in Tahoe City in 2022, courtesy photo

Tahoe Calling

When Dublennikova met her partner, Scott Roehrick, in 2017, he had just returned from a trip to Russia, and the two hit it off. They began dating and eventually moved in with Roehrick’s family in Modesto to save money, with ambitions to buy a home in Tahoe—the site of Roehrick’s favorite childhood memories.

The first time Dublennikova visited Lake Tahoe, the Basin was dazzling in a fresh coat of white.

“I thought, ‘Oh my god, snow!’ I hadn’t seen it for such a long time, but here it was like a winter wonderland. My face wasn’t frozen, it didn’t hurt. I was amazed by it,” she says. “I remember seeing my first sunset (in Crystal Bay). I thought about how lucky I was to be alive in this place, but I never thought I could live here.”

The opportunity to buy a home in Truckee arose in 2020, and Dublennikova and Roehrick—along with their rescue dog, Sabai—settled in a house with “pine” in its street name.

“I always dreamed of living in a forest, but not too remote, so it’s a dream come true for me,” Dublennikova says. “Honestly, I didn’t think it was possible. It’s amazing to be so close to nature. I love being part of our small community.”

While working remotely during the pandemic as a graphic designer, Dublennikova quickly realized she did not want to sit and look at a screen all day. So she tapped into her family roots working in the dachas and launched a website in 2020 offering an array of plants and services, from repotting to consultations to a unique artform in which she crafts intricately designed wall hangings using moss and wolf lichen, which keeps its radiant colors without requiring any maintenance.

“I love plants, love trees, and I think I’m good with them,” says Dublennikova, who created a logo with bold red and yellow—“very Russian colors”—and a kind of folklore background. “I wanted a logo with a modern take on Russian tradition,” she says.

Kindred Spirits

It was around this time that Ayana Wicker and her husband, Andrei Soroker, found Dublennikova through Nextdoor.

“I had been talking about wanting to have plants in the house, but I didn’t know what was good to grow up here,” says Wicker, who was looking to liven up her home’s dark interior.

She bought some plants from Dublennikova, who got her truck stuck in the snow next to their house during the delivery. Soroker helped pull her out, and while chatting they realized they were both from Siberia. Soroker, who grew up in Novosibirsk, and Wicker even have a 12-year-old daughter who is learning to speak Russian and has the same name as Dublennikova’s sister.

During the pandemic and later the Russia-Ukraine war, the couple found a kindred spirit in Dublennikova.

“Anya goes above and beyond. I feel extremely connected to her. I always feel like I can go in and talk to her, and that really sticks with Andrei because he doesn’t really speak Russian in public,” Wicker says.

Regarding the war, she adds, “Anya handles it well. I see a whole different view … in our house there was this attitude of, ‘Don’t tell anyone you’re Russian,’ because of the backlash that we could incur. But Anya is light and joyful, and [the war] has nothing to do with plants.”

Blossoming Business

As Dublennikova established a reputation for her services—as well as her radiant personality—her business began to grow.

She caught a break in spring 2021 when J.D. Hoss allowed her to run a pop-up shop in front of his flooring business on West River Street on weekends. Good Anya moved into a small space next to Truckee’s Wild Cherries Coffee House in October 2021, then into a roomier location in the same complex in July 2023.

Anya Dublennikova’s positive energy is appreciated by all who visit her shop, photo by Ryan Salm

Dublennikova describes her customers as a combination of people who got into plants from being stuck at home during the pandemic to longtime gardeners who have been into growing things forever.

“People come in here and they say, ‘OMG, this is so cute. All the plants are so happy and have a smile on their face,’” says Dublennikova, who walks people through how to care for their new purchase and collaborates with interior designers on styling with plants. “Plants bring life into a space,” she says.

Wicker admits that when she found Good Anya, she had little experience growing houseplants and was a bit intimidated at first. “But [Anya] is like a teacher,” she says, “like a grandma.”

“It’s important to remember all the good things we have in this life and surround yourself with plants and things to care for,” Dublennikova says. “The goal is not to kill the plant but for customers to come in and tell me that their plant is thriving, and they want more.”

Wicker is proud to admit that she still has all the plants she bought from Dublennikova four years ago—all 10 of them—and that she even gave her daughter a plant to care for. “So now she’s in the club,” Wicker says.

Kayla Anderson is a North Lake Tahoe resident of 18 years who loves being outdoors, especially in the Tahoe National Forest. While she is not known to have a green thumb, she appreciates how plants can breathe life into a space along with the amazing people who care for them.

No Comments