27 Jun Atom Bombs, Uncle Harvey and a Lifelong Love for the Sierra

A hall-of-fame skier’s early rambles in the Tahoe Basin sparked a passion for mountain adventure

“All true paths lead through mountains.” -Gary Snyder

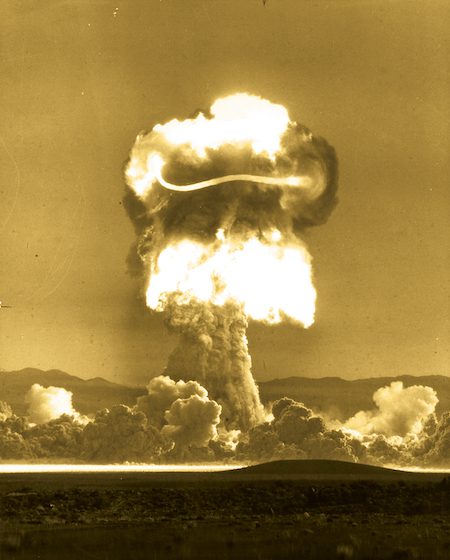

An atomic bomb is detonated in Nevada in 1957 as part of Operation Plumbbob. Beginning in 1951, the U.S. conducted more than 1,000 nuclear tests in Nevada, some of which could be seen through the dark of night from as far away as Kingsbury Grade above Lake Tahoe’s southeast shore, photo courtesy National Nuclear Security Administration

I was almost 7 years old when World War II ended in 1945, and my mom, dad and I lived very different lives during the previous four years. Dad was in charge of a military warehouse on Guam, mom lived with two of her sisters in Oakland, and I lived in a series of boarding houses in Oakland, Richmond and Berkeley. I saw my mother every other weekend for a few hours or sometimes a day. When we reunited, we moved to Lake Tahoe and began to put our wartime-fractured family back together.

To my father, the atomic bomb ended the war and meant he got to go home. In homage and celebration of his presence, when the U.S. government began detonating atomic bombs in the deserts of Nevada in the early 1950s, our family would get up early in the morning, drive up Kingsbury Grade between Lake Tahoe and Genoa and sit on the ground wrapped in blankets, watching the bombs light up the dark southeastern sky.

More than 70 years later, I can still picture the distant horizon vertically turning the whitest of whites, followed by an even whiter white horizontal flash against the breast of Mother Earth that left a nauseous feeling in my young instincts, which can always be trusted if not easily understood.

The rare glimpse of such a destructive force created an uneasiness I’ll never forget (those interested in the consequences of the tests should read American Ground Zero: The Secret Nuclear War by Carole Gallagher). But while the memory remains disturbing to this day, it represents one of many formative life experiences gleaned from a childhood that was far from perfect, yet full of beauty and intrigue thanks to the mountain paradise I was fortunate enough to call home.

Landing in Paradise

I will never forget the day our family drove into the Sierra and entered the Tahoe Basin from Echo Summit.

As I have written elsewhere: “It was a springtime blue sky day with snow on the ground and freedom in the hills waiting for me to join her. My instincts spoke directly to my young soul, welcoming me home and telling me that whether I lived in a palace with loving family or a rooming house with strangers, my home would always be in the mountains.

Author Dick Dorworth with his son Jason and father Al by the Truckee River in the mid-1970s, courtesy photo

“It was a gift, a mystery, a compass and a path for life as natural as breathing, as sure as the heart of love.”

We moved to Lake Tahoe because my uncle, Harvey Gross, had made money illegally dealing in the sanctioned staples of booze and beef and was building what became Harvey’s Wagon Wheel Saloon and Gaming Hall. Located just inside the Nevada state line on Tahoe’s South Shore, the casino—now Harveys Lake Tahoe—earned fame years later when its high-rise hotel was destroyed in August 1980 by an intricate bomb designed by a disgruntled customer named John Birges Sr.

Some three and a half decades before the incident, my dad helped build the original Wagon Wheel before its opening in the mid-1940s. He then worked as a bookkeeper, as well as a blackjack and craps dealer, while my mom worked as a waitress, change girl and sometimes a cook (it was not until the 1950s that women were allowed to work the better-paying jobs).

My folks generally worked double shifts during the summer tourist season, leaving me largely unsupervised for three months of the year. The rest of the year they drew unemployment while working cash jobs on the side and doing everything in their power to support my newfound love for skiing and self-determination, which I achieved through long solo rambles in the mountains around Tahoe.

Some might (and did) consider such parenting as “benign neglect,” but I think of it as an invaluable gift.

Mountain Memories

One summer day in 1950 (or perhaps 1951), my buddy John Robinson and I had a day in the mountains that changed something—perspective, scale, possibility or maybe direction—inside. I knew it then and remember it now, and I never see that area of the Sierra without smiling.

The day stays in mind because it was the biggest of its kind in that pre-teenage Tahoe time when summer rules and parental supervision started and ended with the admonition to be home for dinner. Whether it was trust and confidence in our basic instincts and capabilities or uncaring neglect of parental duties, the children of Tahoe in the post-WWII era had a great deal of latitude and personal freedom.

My folks probably thought I’d gone to the beach the day John and I headed to what we called Eagle Rock, a remote, romantic, mysterious outcrop visible high above and to the northeast of Kingsbury Grade. It seemed unreachable until we decided to reach it, and then it became a huge goal that gladdened our hearts from the moment we embarked.

I was 11 or 12, John a year older, when we set off from Tahoe’s South Shore along Highway 50 and up the narrow dirt road of Kingsbury, filled with our quest and the self-sufficient knowledge, even glee, that no one in the world knew where we were or what was our goal.

After a couple of hours we veered off Kingsbury into unknown terrain of pine, fir, aspen and manzanita, the evergreen shrub, sprouting out of the sandy soil. We were guided by a general sense of direction and the pure joy of going where we had never gone before, secure in the knowledge that even as we plodded up, always up, with fatigue taking its toll on body and motivation, turning around and going down would eventually get us back to Tahoe—the familiar, home, dinner.

Dorworth skis in Verbier, Switzerland, during a Warren Miller film shoot in 1975, photo by Tom Lippert

John was big for his age, strong, athletic and a fine skier. We encouraged each other to continue in those times when we could see neither Eagle Rock nor Tahoe and the dominant constants were the upward slope, the downward slide of our energies, our companionship and that ineffable something that had inspired us in the first place.

We went on for hours and then late in the day finally gained the ridge and scrambled up Eagle Rock on top of our world, the backyard of my childhood, the Sierra Nevada. To the east lay the Carson Valley and the high desert mountains of Nevada. To the west was the Tahoe Basin holding the Lake of the Sky, nature’s own bassinet, and looking around from the summit of Eagle Rock was the most exciting and wonderful thing I had ever done.

We went back down and I made it home for dinner and never told my parents where we had gone. After that day I always knew solace and meaning were mine for the taking, always there to be explored and experienced in my own backyard, just one step away from the highways and byways of civilization, no matter where I may be.

Winter memories from that era abound as well, many of them centered on skiing.

Near our home in Zephyr Cove, I kept a slalom hill packed in practice shape. For slalom poles I used willows, cut and stripped with a handsaw and sharpened at the thick end for easy insertion in the snow. The basic foundation of my skiing knowledge was built on that slalom hill. Thanks to the freedom I had to build my own course and train on it, I was largely a self-taught skier who relied on experience that could not be taken from me.

Outdoor Therapy

My coveted outdoor experiences as a child were far removed—if only for a few hours—from the confusion and periodic waves of alcoholic sorrow that washed across my family. More than 50 years later, during a sad period, I often went backcountry skiing alone. A skier friend who never ventures off the beaten path without a group asked why I skied alone, where no immediate help was available in case of an accident.

“Therapy,” I replied without hesitation.

I have written elsewhere that “skiing and, more specifically, ski racing probably saved my life, allowing me to grow into a social critic instead of the sociopath I might have become in response to society’s violent and small-minded hypocrisies, pretensions and shallow smugness. Skiing kept anger, adolescent hormones and confusion in check enough to focus on a path that was to take me skiing all over the world. It formed and informed my life at least as much as the dynamics of family, the structure of schools, the warmth and generosity of true friends, the betrayals of false friends and the other (and normal) vicissitudes of life.”

A Lasting Gift

My mom was a voracious reader of pop trash detective novels of the Erle Stanley Gardner-Mickey Spillane-Agatha Christie genre, though she also read current bestsellers. Among her legacy to me are a love of literature and the benefits and tools of life to be found in a good book.

Author Dick Dorworth climbs at the Elephant’s Perch in Idaho around 2005, courtesy photo

It has long intrigued me that she directed me to a higher standard of literature than she read. I think it was how a working woman with a high school education and a difficult childhood and marriage encouraged her son to a better life than her own.

I still have some of the books she gave me before the age of 12, including the Essays of Michel de Montaigne illustrated by Salvador Dali, The Travels of Marco Polo and, to illustrate her quirkiness, Archy and Mehitabel, Hans Brinker or The Silver Skates, the stories of Jack London and everything by Mark Twain. In those pre-TV days as the only child of heavy drinkers who had trapped themselves in a contentious, dysfunctional relationship, books were a savior, refuge and direction that I loved and needed.

As a result of this unique childhood, I knew by an early age that my life would be devoted to skiing, writing and the great outdoors. Almost 20 years later I was introduced to rock climbing, and these activities have defined much of my life. Along the way I discovered I enjoyed teaching as well, and for many years I passed on to others my knowledge and love for skiing, climbing and learning.

Reflecting on life at age 84, I’m eternally grateful to have spent my formative years at Lake Tahoe, where I received an invaluable education immersed in what I have described as “the most beautiful, exotic landscape imaginable.”

And it was all because Uncle Harvey made some money illicitly dealing in black market booze and beef. Thanks, Harvey.

Editor’s note: Portions of this article are from previously written work by Dick Dorworth.

After his Tahoe upbringing, Dick Dorworth went on to a successful skiing and writing career, earning a spot on the All-American Ski Team at the University of Nevada, Reno, setting a world speed skiing record of 106 miles per hour, publishing seven books and writing for dozens of publications. Now a resident of Bozeman, Montana, he was inducted into the U.S. Ski and Snowboard Hall of Fame in 2011. Find more of his work at dickdorworth.com.

No Comments