27 Jun Shawn Estes: Finding His Form

The Northern Nevada native and former San Francisco Giants ace is savoring his second act as a big-league broadcaster

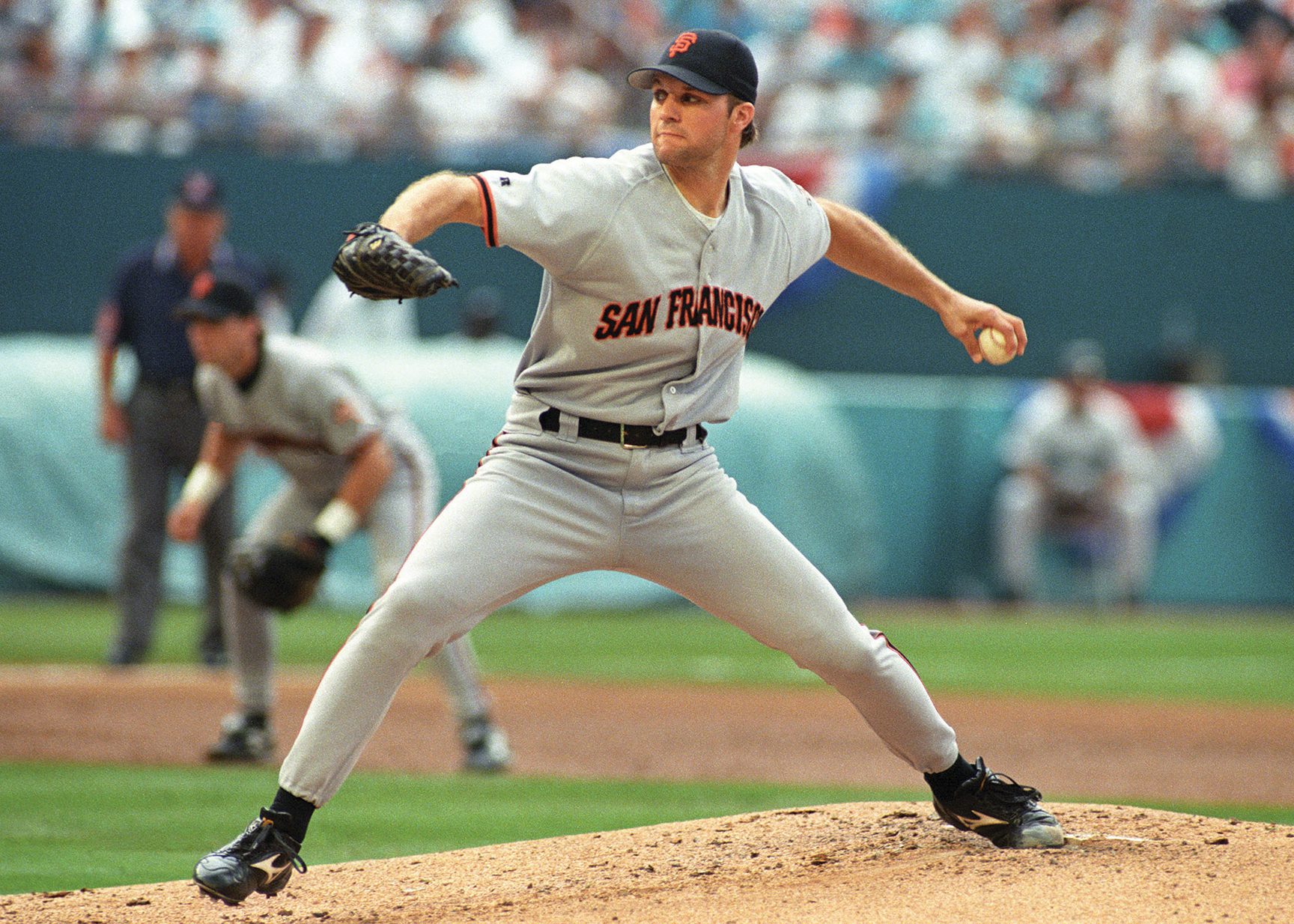

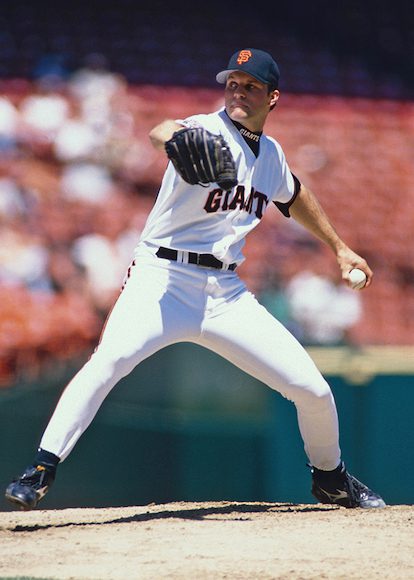

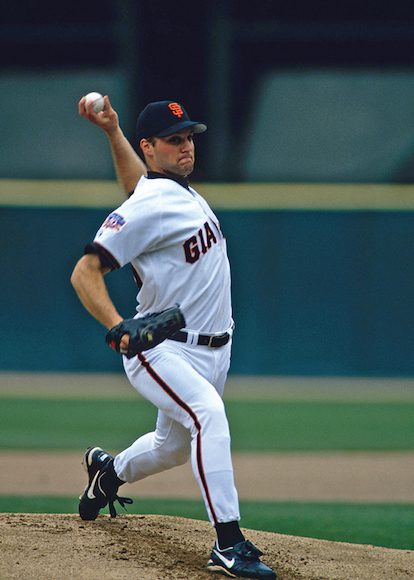

Estes during his seven-year run with the San Francisco Giants, the team he grew up watching, photo courtesy © S.F. Giants

Shawn Estes was on a much-needed sabbatical.

It was the summer of 2010, and for the first time since he started throwing a baseball on fields in Minden, Nevada, the 37-year-old major league pitcher was not on a team. No games on the schedule. No injury-riddled ballclubs calling his phone. Nothing.

“I was just done, mentally, with baseball,” Estes says. “I didn’t even watch baseball—I didn’t watch a game. I just wanted to get away from it all.”

Earlier that year, while trying to get back to the big leagues, the former Douglas High School standout was hit with the reality that his playing days were done. In February 2010, Estes signed a minor league contract with the Washington Nationals, who had the worst record in the league the year before with 103 losses.

“I was just trying to see if I had anything left,” says Estes, who spent the previous season battling injuries in the minors. “I was like, ‘If I can’t make this team, I’m not making any team.’”

A month later, Estes was cut. Nearly two decades after his professional career began, and 15 years after his major league debut, the Northern Nevada native hung up his glove for good.

“I remember walking out of there knowing, OK, I have closure now,” he says.

And so he did what a lot of retired ballplayers do. He swung golf clubs. Saw more of the world. Savored long days with his wife and kids.

But after six months, the retirement shine started to wear off. Estes found himself gravitating back to baseball—watching it, analyzing it, missing it. It wasn’t that he wanted to be a ballplayer again. Returning to a routine of red-eye flights and hotel rooms and ice-wrapped shoulders and long-distance calls to his wife was not appealing. Estes realized, however, that he wanted—needed—to be around the game in some capacity.

“I did some soul-searching,” he says. “I knew that I needed to do something to keep my mind active.”

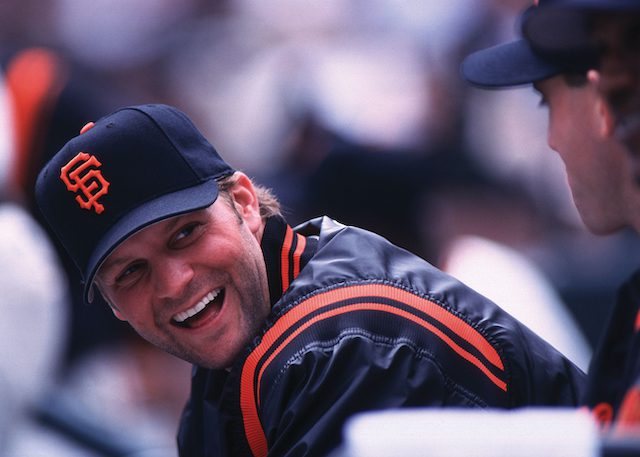

Former San Francisco Giant and Northern Nevada native Shawn Estes returns to Tahoe annually to visit his childhood stomping grounds, photo courtesy © S.F. Giants

‘A Local Hero’

Growing up in Minden, a small town 20 miles east of Lake Tahoe, at the foot of Heavenly ski resort, Estes had no trouble staying busy. If he wasn’t in school or at home, he was outside—in his backyard or at a ball field—flinging a baseball.

“I had the goal of being a major league player around the age of 12,” says Estes, whose favorite player was legendary pitcher Nolan Ryan.

For some kids, that kind of goal is a pipe dream. Not Estes. The young left-hander was already striking out hitters like clockwork. And his speed and velocity, and breaks in his curveball, were only getting better.

At Douglas High School, Estes was an absolute force on the mound for the Tigers. He finished his senior season in 1991 with a 0.79 earned run average and 141 strikeouts, including a 20-strikeout game in eight innings. His single-season strikeout total was a Nevada state record among large schools that stood for over 30 years until it was broken this past spring by McQueen’s Robby Snelling. Estes also batted .488 with eight home runs. At season’s end, he was awarded 4A State Player of the Year.

“Shawn was a local hero,” says Joey Crandall, a former sports editor for the Record-Courier in Minden. “For every kid who grew up around here, it wasn’t just a dream to grow up to play in the big leagues, it was knowing that the guy down the street actually made it.”

Estes says his head coach at Douglas, Hal Wheeler, and pitching coach, Rick Kester, had big influences on his career. Kester, who pitched for the Atlanta Braves for three seasons, taught him the proper mechanics and grip of a knee-buckling curveball.

“Coming out of high school, I had all of the confidence in the world,” Estes says. “I thought I was the best pitcher in the country.”

Many professional scouts thought the same. In fact, Estes was considered a top prospect in the 1991 MLB draft. As a result, he decided to surpass college ball despite committing to play at Stanford University. Instead, he turned pro, selected 11th overall by the Seattle Mariners. Only months removed from donning his high school cap and gown, Estes was suiting up for a professional baseball team, the Mariners’ single-A ballclub.

The strikeouts and wins didn’t come as easy anymore. Consequently, his confidence took a hit.

“I was humbled right away,” he says. “I was not having any success at all, and really started to question or have doubts about making the big leagues.”

Minden native Shawn Estes enjoyed a 15-year career in the major leagues, photo courtesy © S.F. Giants

Living a Dream

After “spinning [his] wheels” in the minors for a few years, Estes decided to strengthen his body and brain. He put in long hours with professional pitching coach Ron Romanick and had weekly sessions with Gary Mack, a renowned sports psychology consultant who counseled pro athletes.

“That was the year everything clicked for me,” he says. “When I came to spring training, I was a completely different pitcher, both mentally and physically.”

The next season, 1995, Estes made his MLB debut—but it wasn’t for the Mariners. The southpaw was traded to the San Francisco Giants. It was not only the team Estes grew up watching, but also the club his dad had rooted for since childhood.

“When I got traded to the Giants, it was a dream come true for me,” Estes says.

His campaign with San Francisco got off to a slow start. He went 0-3 in three outings and was sent back to the minors.

“I knew I didn’t belong in the big leagues after that,” he says.

That changed the following season. Estes, who was making a name for himself in the minors, got called up to pitch against the Giants’ longtime rival, the Los Angeles Dodgers—in Dodger Stadium.

He rose to the occasion and then some, working seven shutout innings and striking out 11 to record his first career major league win.

“After that game, I said, ‘I’m here to stay.’ I finally did what I needed to do to stay in the big leagues,” Estes says. “It’s not just getting here; now I can pitch here and have confidence.”

His confidence only grew from there. In fact, in 1997 the young Giants starter was one of the best pitchers in all of baseball. He went 19-5 with a 3.18 ERA and was selected to the National League all-star team.

“As a player, he made something really hard look really easy,” says Mike Krukow, a former major league pitcher and longtime color commentator for the Giants. “He was a gifted pitcher and always fun to watch. He always had that little ‘smile of the scamp.’ He was just playing in the big leagues and having the time of his life.”

In the process, Estes helped lead the ’97 Giants to a first-place finish in the NL West with a 90-72 record. Their season ended in the National League Division Series, swept by the Florida Marlins, who went on to win the World Series. Still, the Giants were back to being a contender, only one year removed from placing last in their division and losing nearly 100 games.

“It was a special year, personally, and from a team standpoint,” Estes says. “It was probably the most fun I’ve ever had in a baseball season.”

After seven years with the Giants, Estes bounced around to a variety of clubs—the Mets, Reds, Cubs, Rockies, Diamondbacks and Padres. Injuries were nagging, cutting his seasons short. After missing most of his first two seasons with the Padres due to Tommy John surgery, he finally was back on the hill in 2008.

He didn’t know it at the time, but it would be his last season pitching on the big stage. He finished his major league career with a 4.71 ERA and 101-93 record. Of note, in 2000 while with San Francisco, Estes became the first Giants pitcher since 1949 to hit a grand slam.

Following two years of unsuccessfully trying to get back to the bigs, Estes was at his Arizona home in the summer of 2010, bored and restless, tired of retirement, searching for his next calling.

A Second Career

And then he got a phone call from John Feeley, an executive at COMCAST Bay Area (now NBC Sports Bay Area), whom he knew from his playing days with the Giants.

“He said, ‘You should get into broadcasting. I think you’d be good at it,’” Estes recalls.

Later that fall, he nailed his interview with the COMCAST news directors. So much so that they asked if he could stick around to do the pre- and post-game show for Game 1 of the Giants’ first-round playoff series against the Braves—a live audition, of sorts.

“I said, ‘I haven’t watched the games this year. I don’t know what’s going on,’” Estes says with a laugh. “I didn’t want to ruin this opportunity to work in this industry by falling on my face. They said, ‘You know baseball. You know pitching. You’ll do great.’”

Estes wasn’t so sure, but he trusted their judgement. Two days later, he was in a button-up and blazer, looking into a camera, breaking down the Giants’ Game 1 win.

“I thought it went terrible,” he says. “I was good at conversation, I was good at answering questions to the media, but I wasn’t good at staring at a camera and getting zero feedback.”

It went better than he imagined. Estes was offered a full-time gig to do the Giants pre- and post-game shows the following season. Helping matters, former Giants outfielder F.P. Santangelo, who had been in that role, took a job as a color analyst for the Nationals.

“That opened up a spot and they hired me,” Estes says.

Mastering a New Craft

Estes says his early years in the broadcast booth reminded him of his early years on the mound as a pro pitcher. The more reps he took and the harder he worked, the less he stressed, and the more comfortable he felt.

“More than anything, the challenge was to just be myself,” says Estes, noting that in his initial season as an analyst he often sounded like “a robot” on the air. “And it was realizing that you don’t have to be perfect. I was finally able to laugh when I screwed up—and have some fun. It’s supposed to be fun.”

Getting tips and encouragement from his broadcasting teammates has helped, too. That includes Krukow and his longtime broadcast partner, Duane Kuiper—known affectionately by Giants fans as Kruk and Kuip.

“With Shawn, his learning curve was pretty quick,” Krukow says. “He got in there and ‘stuck his finger in the fan’ and just saw where it would go. It was just a matter of learning the timing of the booth. And he found comfort and won an audience. The Giants fans love his voice.”

In 2019, after eight years doing pre- and post-game shows, Estes got called up to the in-game booth. He started filling in as a color commentator for Krukow, who was taking off occasional road games. Krukow, who lives in Reno, has a rare inflammatory muscle disease that affects his mobility.

Quickly, Krukow was impressed with Estes’ broadcasting talents during games, just as he was awed by his abilities as a pitcher decades ago.

“You could just see how he evolved as a broadcaster,” Krukow says. “I think the one thing that separates broadcasters from the herd is your ability to forecast. Talk about what’s happening in a game and then forecast what you’re seeing into a situation and be able to create that anticipation with the listening audience.

“And when you’re a big leaguer who’s played as long as Shawn, he’s experienced just about everything in the game, so he knows the way that a game is trending; he knows which side of the field the momentum is on; which dugout the momentum is in.”

That said, Krukow quips, “It pisses the rest of us off how good-looking he is.”

Forecasting the 2022 Giants

Estes thinks this year’s Giants squad has a chance to mirror the success they had a season ago. That team wildly exceeded the expectations of fans and media alike, coming out of nowhere to capture the best record in the regular season with 107 wins. San Francisco’s postseason ended in the first round, falling to the Dodgers, 2-1, in the deciding Game 5 on a controversial check-swing that was called a strike.

Estes acknowledges the departure of catcher Buster Posey and pitcher Kevin Gausman are big losses. But he still thinks the Giants have the makings of a contender. He feels especially strong about the pitching rotation led by ace Logan Webb, a Rocklin native.

“Every time they take the field, they have a chance to compete,” Estes says. “I feel like this team can win 90 games, minimum.”

Finding Time for Tahoe

When he’s not analyzing the Giants and their opponents before, during or after games, Estes is chasing around his four kids in Scottsdale, Arizona. Sometimes, that involves watching Little League and high school ball.

During the offseason, he occasionally returns to the greater Reno–Tahoe region to visit family and, if the conditions are right, hit the slopes.

“I try to get back there every year and ski,” says Estes, who has a timeshare next to Heavenly, where he learned to ski as a kid.

The topic of Tahoe, naturally, drifts his mind back to his childhood. Fireworks at Nevada Beach. Beach volleyball at Zephyr Cove. Spring and summer ball games against the Tahoe teams.

“I spent a lot of time there as a kid,” Estes says, a hint of nostalgia in his voice. “Tahoe is just so unique in what it has … the beauty in the winter and the summer and all of the outdoor stuff to do.

“I really enjoy getting back to the area.”

Kaleb M. Roedel is a Reno-based writer and baseball fan.

No Comments