26 Apr Steve McKinney: Transcending the Continuum of Excellence

More than three decades after his death, Steve McKinney’s legacy endures as one of Tahoe’s best athletes and most dynamic personalities

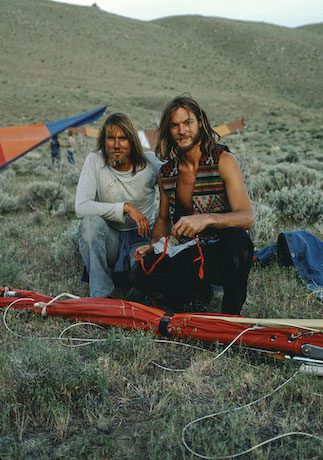

Steve McKinney, right, with fellow Tahoe speed skier and friend Paul Buschmann. The two were testing hang gliders before an early attempt to fly off Mount Everest, photo by Eric Perlman Productions

Steve McKinney was one of the best all-around athletes in Tahoe history. Given the long line of exceptional athletes who have called this region home—dating back to the skiing pioneers of the mid-nineteenth century—that is saying a lot.

McKinney was revered in his era, but excellence in all things is a continuum, not a destination, and he was only one of many in the Tahoe community who expanded the limits of the athletically possible. Among Tahoe’s elite tier of athletes both past and present, however, McKinney will forever hold a place near the top of the list.

Born in 1953—and tragically killed in 1990 by a likely drunk driver—McKinney is perhaps best known for his speed skiing. He held the world record several times, first in 1974 when he skied 117.773 miles per hour in Cervinia, Italy, and last in 1982 when he blazed down a course in Les Arcs, France, at 125.038 miles per hour. But his athletic abilities extended far beyond skiing. He was also a superb rock climber, mountaineer, backcountry skier and hang glider pilot—activities he pursued with the same passion and attention to detail that made him an integral part of Tahoe’s continuum of athletic excellence.

As was his gracious and thoughtful nature, McKinney if he were alive today would give due credit to his predecessors for the path they helped pave.

The Athletes Who Paved the Way

The first great Tahoe skier, of course, was John Albert Thompson—better known in skiing lore as Snowshoe Thompson.

An 1889 illustration of John “Snowshoe” Thompson carrying mail over Echo Summit, courtesy image

Born in Telemark, Norway, in 1827, Thompson moved to the United States with his mother at age 10 and lived in several states before settling in Placerville, about an hour’s drive west of Lake Tahoe, in 1851. He is known as “the father of California skiing” because between 1856 and 1876 he delivered mail from Placerville to Genoa, Nevada, in the dead of winter along a route over Echo Summit approximately where Highway 50 is today. He made the trip several times each winter, taking three days eastward and two days back west while traversing the high country on 10-foot-long, hand-carved wooden skis known as “snowshoes.” He was propelled and guided by a single sturdy pole.

While Thompson’s numerous ski tours across the Sierra seem almost unfathomable today, so too do the feats of the gold-mining skiers in the Lost Sierra north of Tahoe. Unlike Thompson, however, their exploits were more aligned with McKinney’s in that they made history through sheer speed.

I have written elsewhere (edited here for style): “The first recorded speed skiing record was in 1867 in La Porte, California, by a woman with the provocative name of Lottie Joy, who traveled 48.9 miles per hour. The length of her run and the method of timing are unknown, making hers one of several unofficial but significant world speed skiing records. The second was also in La Porte by Tommy Todd, who traveled down a 1,230-foot track in an average speed of 87.7 miles per hour in 1874. If Todd’s timing was anywhere near accurate, it is not unreasonable to speculate that he was traveling near 100 miles per hour during that last part of his run. …

“It needs mentioning that while Joy was the first speed queen and Todd the first speed king, they are only the first we know about. People have been skiing for thousands of years, and it is inconceivable that they have not always pursued pure speed for the sake of speed. It is in the nature of man to do so, and that we do not have speed skiing records prior to 1867 only indicates the relative and incomplete scope of recorded history itself.”

A Cut Above

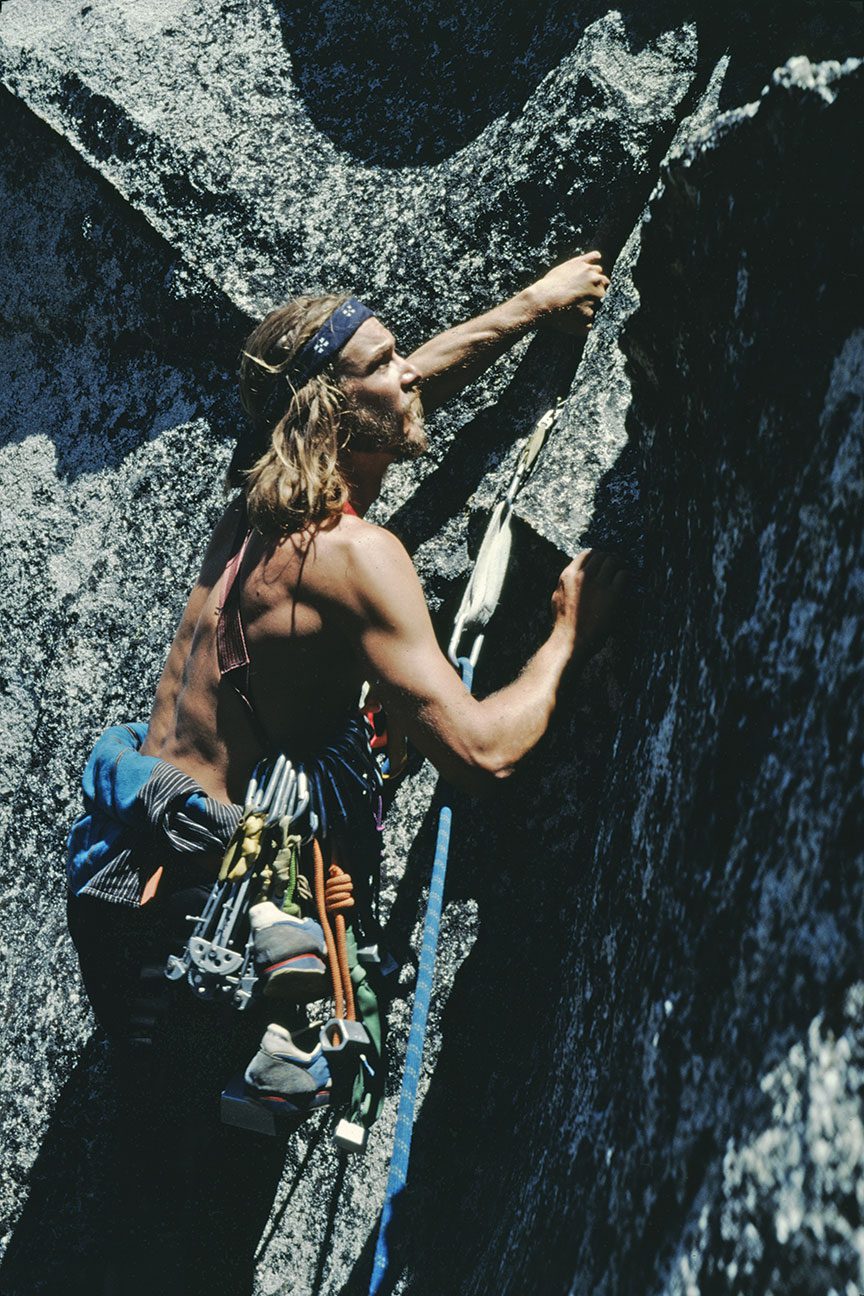

McKinney, like many of Tahoe’s winter athletes before and after him, was a rock climber in the summer who frequented the numerous fine (and a few not so fine) rock formations in and around the Tahoe Basin. Rock climbing and skiing, especially skiing at high speeds, both require complete attention in the present moment and the ability to recognize without giving into fear. As such, they are complimentary activities.

Steve McKinney bombs a run at Mammoth Mountain in the 1970s, photo by Eric Perlman Productions

In 1972, McKinney decided to take up the two endeavors at the same time. Unfortunately, before he could embark to Cervinia, Italy—the center of speed skiing at that time—for the annual Kilometro Lanciato week of speed runs, he broke his back in a climbing accident on Donner Summit and wound up in a cast from neck to waist.

McKinney continued to ski and went to Cervinia in 1973 in his cast and watched the races, studied the competitors, became friends with several of them over dinners and late-night parties, and, most importantly, learned what they were doing on the track and how to improve it. A year later he returned to Cervinia in superb physical, mental and spiritual condition and set the first of his world records.

In a memoir of McKinney, I wrote: “The world of speed skiing would never be the same. Steve was the right person in the right place at the right time to attract the media’s attention and give speed skiing a public profile it had never before known. Steve exemplified that elusive term ‘charisma.’ He had the 6-4, 190-pound physique of a Viking warrior, the long blonde hair and good looks of a rock star, the confidence of a king, the personality of a fun-loving sage, and he was THE MAN in an endeavor that answers a question that occurs to every person who has ever put on a pair of skis, even to those who do not wish to find out the answer: How fast can I go?”

An Accomplished Life

Rock climbing in the Tahoe area gained popularity in the 1960s, though it is known that in the 1950s a few people were cragging, and it is inconceivable that others were not earlier. A few weeks after McKinney was out of his body cast, he began climbing again, including a successful repeat on the route from which he fell and broke his back.

In the same memoir of McKinney, I wrote: “Steve became a serious and accomplished mountaineer in the 1980s. He climbed 24,785-foot-high Mustagh Ata in the Chinese Pamir Mountains. After returning from the summit he turned around and climbed it again to help a British double amputee (both legs below the knee) accomplish his goal of reaching the peak. Steve was on two expeditions to Mount Everest. On the first one he was instrumental in saving the life of John Roskelley, one of America’s greatest climbers, who came down with pulmonary edema at 25,000 feet and was practically carried off the mountain by McKinney. On his second expedition he flew a hang glider off the West Ridge of Mount Everest from 22,000 feet despite an earlier crash at a lower elevation on a trial flight.”

Beyond his athletic endeavors, McKinney was an accomplished musician, writer, deep thinker, philosopher and kind, compassionate human. He was raised as a McKinney, but his mother and biological father divorced before he was a year old and he never met his real father. When he was 22, he decided he wanted to make the connection to a lost part of his life and phoned his father, who lived on the East Coast.

His father was still angry that his mother had divorced him and moved across the country and remarried. As so often happens, parental feuds are carried on the backs and psyches of their children. He rejected his son immediately with the admonition to never contact him again. Steve didn’t.

He was crushed, confused, hurt and sorrowful, but he said, “I know one thing about that guy: He was doing the best that he could do with what he had to work with at the time.”

That is, one of the reasons Steve McKinney knew about doing the best that he could do with what he had to work with was that he did just that in all things, not just athletics, with a love and compassion that transcended the continuum of excellence and inspired others by his example to do the same. And they continue to do so.

A Tahoe native who now lives in Bozeman, Montana, Dick Dorworth is a noted ski racer, coach and world record holder who was inducted into the U.S. Ski and Snowboard Hall of Fame in 2011. Dorworth, who has published seven books and written for dozens of publications, was a good friend to the McKinney family and a mentor to Steve. Find more of his work at dickdorworth.com.

Thomas Pope

Posted at 18:01h, 31 MarchSteve was my first Speed Skiing teacher in the camel sprint series – an introduction speed skiing in 1984 . I Remember his words of going fast and having fun and trying your best.

I went onto winning a speed skiing race at mount rose NV , placing in top 10 at other camel sprint races, I was invited to race i.n France French Cup and World Championship in La cuz a France . And I raced the debut FIS World Cup speed skiing championships as team USA racer In Oregon in 1990 I put full credit to my towards my success and point to the great steve McKinney- my teacher and life long long mentor