27 Sep The Incandescent Life and Untimely Death of Spider Sabich

The world-class alpine racer from Kyburz lived the high life of a 1970s skiing celebrity before one tragic day in Aspen ended it all

When Spider Sabich and Claudine Longet first met at a celebrity ski race event in Bear Valley, California, they both carried their respective worlds in the palms of their hands.

Sabich was a lauded professional skier from a small town just outside of Lake Tahoe, regarded as one of the best technicians of his generation. He was blessed with golden-locked good looks and a magnetic personality, all of which helped to propel him toward the zenith of the 1970s sports world, popularizing downhill racing in the process.

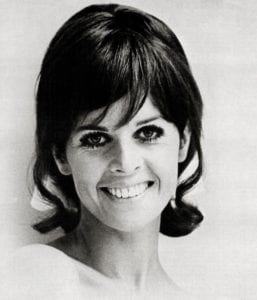

Longet was a French actress, singer and dancer whose face was strewn across the silver screen in the 1960s, known for her slender, athletic frame, sultry, doe-like eyes and a clear, subtle voice that carried her 1967 debut album Claudine all the way to number 11 on the Billboard pop album charts in the United States.

The year was 1972. Sabich and Longet were both at or near the pinnacle of their respective fields. They sparked an attraction that was immediate and potent, leading to a torrid four-year affair that culminated in the shooting death of Sabich at the hands of Longet.

Longet shot Sabich in the stomach with an imitation World War II luger pistol while he was showering in his Aspen, Colorado, home. He bled to death before an ambulance could arrive. He was 31.

Longet claimed the gun went off accidentally as Sabich was showing her how to use it.

Police told a different story, saying Longet killed the famed ski racer in a rage after four years of fame, drug use, wild parties and constant turmoil finally took its toll.

Police found cocaine in Longet’s bloodstream and her diary illuminated the inner workings of a tumultuous relationship beset by jealousies and a ceaseless cycle of tempestuous fights followed by passionate reconciliations.

A trial that roiled the burgeoning town of Aspen generated headlines throughout the world, with the prosecution seeking a conviction of felony manslaughter.

Instead, the four-day trial ended with the jury convicting Longet of misdemeanor negligent homicide. She was sentenced to 30 days in jail to be commenced at a time of her choosing, a punishment the Sabich family and many in the community deemed far too meager.

Billy Kidd, a fellow ski racer and Sabich’s longtime friend, says the salacious nature of his friend’s death tends to detract from his brief but incandescent life.

“We all miss Spider,” he says. “He was one of the most charismatic and fun people to ever be on this planet.”

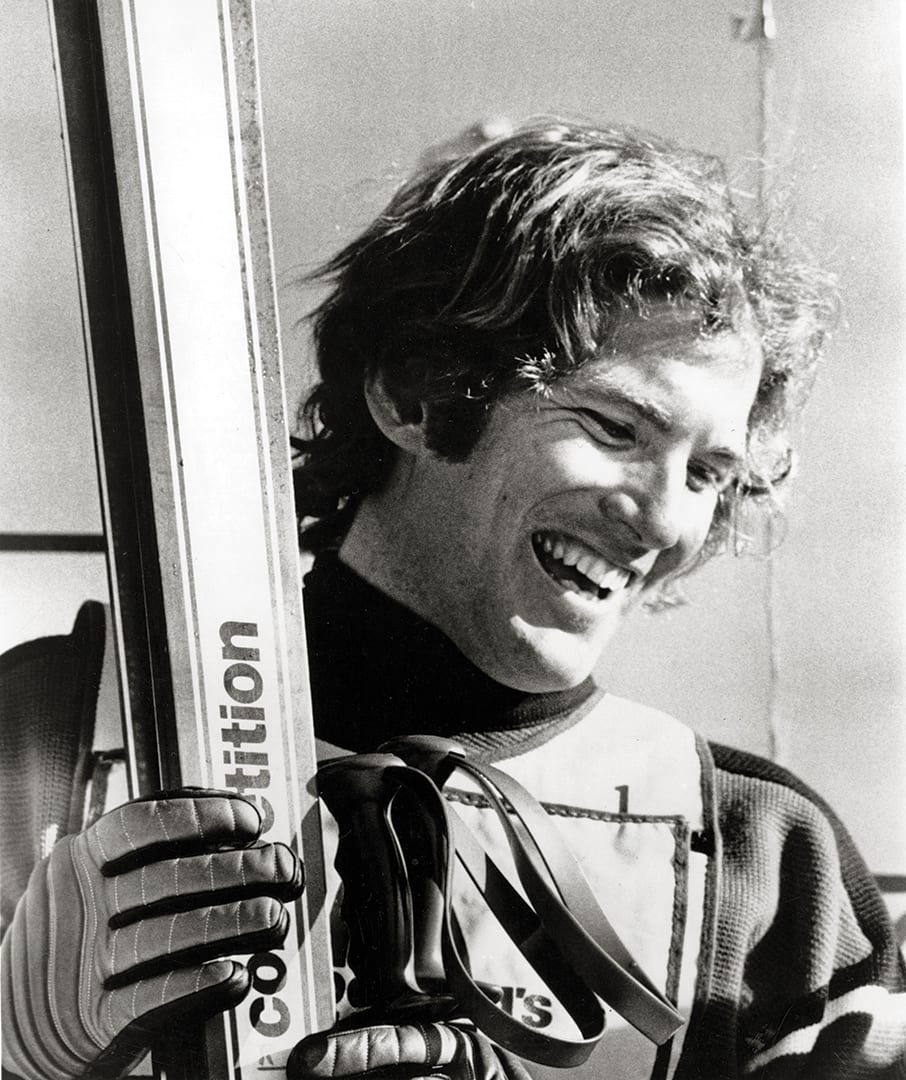

Sabich takes flight during a World Cup race in 1968, photo courtesy Aspen Historical Society, Aspen Skiing Co. Collection

Sierra Upbringing

Spider Sabich’s real name is Vladimir, the same as his father, Vladimir Sabich Sr., a California Highway Patrol officer who was stationed in Kyburz about 25 miles west of South Lake Tahoe during the 1950s. Spider was born premature and was scrawny by nature, with spindly arms and legs, garnering the moniker he would proudly sport for the rest of his life. He was a middle child, with an older sister named Mary and a brother named Steve (who everybody called Pinky) who was one year younger.

“His father was very involved with the kids,” recalls Eric Poulsen, son of Squaw Valley founder Wayne Poulsen, who grew up ski racing with the Sabich brothers. “He got him involved in ski racing and made sure he had good coaching.”

Several of Spider Sabich’s former teammates remember his father dropping off and picking up his kids at the mountain in his patrol car.

Sabich first began skiing at Edelweiss, a now defunct ski resort located about 12 miles up Highway 50 from Kyburz, and later raced at Heavenly. He proved to be naturally adroit in the mountains from an early age.

“He was fearless,” says Jimmy Elsworth, a childhood friend of Sabich’s, in a 2005 interview that appeared in California Conversations. “He didn’t hesitate. He had God-given coordination.”

Poulsen recalls Sabich as an accomplished technical skier with a pronounced proficiency in the slalom.

“He helped me with my own skiing,” Poulsen says.

When he was still in eighth grade, Sabich beat out 17- and 18-year-olds at a ski competition sponsored by The Sacramento Bee and eventually caught the notice of legendary ski coach Bob Beattie, who recruited him to the University of Colorado Boulder. Beattie not only helmed the ski team at Colorado, but coached the U.S. Ski Team at the time as well.

Sabich roomed with Kidd the year he arrived, and the two became fast friends.

The World Cup

“He was just instantly likeable, a typical California kid,” says Kidd. “Within five to 10 minutes, you feel like you’ve known him for a lifetime.”

It was the 1960s. There was no shortage of intoxicants and beautiful women in the town of Boulder.

Sabich skis a slalom course, sans helmet, in 1974, photo courtesy Aspen Historical Society, Aspen Today Collection

“There wasn’t any girl around who from the instant she heard the word ‘hello’ didn’t want to spend more time with him,” Kidd recalls.

With flowing blonde hair, a 10,000-watt smile and an easygoing temperament, Sabich cultivated few enemies against his legions of friends and admirers. His dauntless approach to skiing, which bled over into other aspects of his life, helped cement his allure.

But while the Spider Sabich persona transcended his accomplishments on the hill, he was no slouch after the final beep sounded in the starting gate.

“It’s not like he got lucky in a race or two; he was a legitimate racer,” Kidd says.

During the 1968 Olympic Games in Grenoble, France, Sabich took fifth in the slalom, confirming his status as one of the best in the world. He was 22 and looked to be one of the most promising ski racers of his generation. Less than two months later he won his only World Cup at Heavenly Valley in Tahoe, using his home-mountain advantage to barely edge out his friend and competitor, Kidd.

He finished on the podium three other times in 1969 and recorded 18 career top-10 finishes on the World Cup circuit. All the while, he burnished his credentials as a man who lived the fast life with a devil-may-care abandon.

“He had that legendary status as a guy who parties the whole night before a race, barely made it to the course on time and still won,” Kidd says.

Sabich, left, and Bob Beattie during a pro race, circa 1975, photo courtesy Aspen Historical Society

Kidd says such stories that emerged out of the late 1960s and ’70s had an element of exaggeration about them, but there was a kernel of truth as well, with Sabich known to at least nurse a few drinks on the eve of a big race on several occasions.

By the early 1970s, Sabich didn’t need victories to garner endorsements and attention. He turned professional in 1970 as his former coach, Beattie, had founded a professional league.

The races were a staple on ABC’s Wide World of Sports, a popular Saturday afternoon show in the 1970s, and Sabich’s profile quickly rose. He won championships in 1971 and 1972.

By this time, the prominence of ski racing had risen in the national imagination. Robert Redford and author James Saulter, after following Sabich and Kidd around on the World Cup Circuit and at the 1968 Olympics, collaborated to make a film called Downhill Racer.

The film proved a breakout role for Redford, earned ample critical acclaim, and remains the most incisive cinematic look at ski racing and the danger, competitive intensity and glory inherent in the sport—which Sabich came to embody.

It was around this time that he met Claudine Longet.

Tumultuous Relationship

Longet, who was three years older than Sabich, was born in France to an industrialist father. She was discovered by Lou Walters, who owned a nightclub in Las Vegas. While performing there, she caught the eye of Andy Williams, one of the biggest celebrities of his day. A popular singer with a television variety show, he became enamored of Longet and the two married in 1961, having three children together over the course of the decade.

Longet’s career as an actress and singer took off from there, as she guest-starred in several popular television shows, appeared alongside Peters Sellers in a popular 1968 comedy and became one of the only French-born singers (along with Edith Pilaf) to achieve major record sales in the United States.

Claudine Longet, courtesy photo

By the time she met Sabich in 1972, she had been divorced from Williams for about a year. The fateful meeting precipitated a torrid affair that began almost instantly.

By that time, Sabich was building a house in Starwood, just outside the town of Aspen, Colorado. Aspen had yet to evolve into its present status as a celebrity enclave, home to Hollywood superstars, wealthy magnates, arrivistes, parvenues, and other assortments of the rich and the famous.

It was a formerly quiet town grown restive with an incursion of young hippies who took to the town’s spectacular scenery and liberal leanings. But by 1970, times had changed. Nothing illustrated such changes as much as Hunter S. Thompson’s 1970 campaign to get elected sheriff of Pitkin County on a platform of relaxing drug prohibitions, renaming Aspen as “Fat City” and displaying dishonest drug pushers in medieval stockades in the town square.

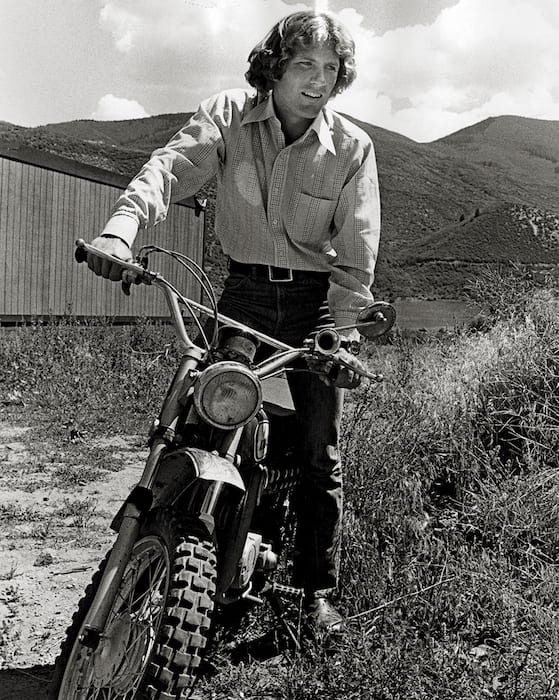

After settling in Colorado, Sabich’s professional ski career wound down after a particularly horrendous crash during the 1973 professional circuit at Aspen Highlands. But Sabich’s characteristically high spirits weren’t dampened as he was content to fraternize with his friend and fellow Starwood resident John Denver and live a wild and energetic version of bachelorhood.

“Spider had cars souped up. We raced motorcycles. We lived on the edge,” says Kidd.

It was into this life that Longet attempted to ingratiate herself and her three children. After the couple moved in together, the following four years were rife with tension and fights. At one particular party, witnesses recall that Longet threw a glass of wine in Sabich’s face for not paying her enough mind.

Sabich truly loved her, according to his friends. Steve Sabich’s widow, Marty Mains Sabich, recalls Longet being the only of Spider’s girlfriends whom he brought home to Kyburz to meet his family.

But the strife continued, and by 1975 Longet was apparently looking to build a separate house in Aspen so the couple could live apart.

On March 21, 1976, Sabich returned to his house after a meeting with his longtime friend and coach, Beattie. The two planned to have dinner in Aspen later that night.

Sabich never made the appointment. He was shot in the stomach that afternoon by Longet while taking a shower. Longet said Sabich was trying to show her how the gun worked, but police immediately doubted her story and placed her under arrest.

The Pitkin County sheriffs bungled two critical pieces of evidence: collecting a blood sample from Longet without a warrant and seizing her diary. The blood sample would have shown Longet had cocaine in her system. The diary would have proved critical to the trial had it been admissible, particularly as it contradicted the assertions she made to detectives that her relationship with Sabich was on firm footing.

The ensuing trial was an international event. Andy Williams accompanied his ex-wife to the Pitkin County Courthouse and testified as a character witness. Actor Jack Nicholson, a friend of Longet’s who had recently repaired to Aspen, sat prominently behind the defense table every day of the trial.

Hunter S. Thompson, who moved to Aspen in 1961 and was no stranger to salacious proceedings, expressed disgust at the trial and its impact on the community.

The subsequent conviction on a paltry misdemeanor and a 30-day jail sentence that Longet chose to serve on weekends didn’t slake the thirst for justice held by the Sabich family and the American people.

Judge George Lohr, who handed down the lenient sentence, said he received copious letters from people around the country who believed Longet was guilty of murder and noted the hostility of many Aspen residents toward Longet.

“In order to kill him, she had to climb on a chair, get underneath Spider’s sweaters, grab the gun, put a bullet in the chamber, go into the bathroom and shoot him,” said Marty Mains Sabich in a 2005 interview.

The Sabich family began civil proceedings against Longet, but eventually settled out of court with the provision that Longet never talk or write about the killing or the settlement.

Remembering a Vibrant Life

Spider Sabich, circa 1975, photo courtesy Aspen Historical Society

Kidd doesn’t like to talk about the killing or the trial or the justice of the punishment. He prefers to focus on his friend’s life in all its unique vibrancy and velocity.

“We just had absolutely incredible times,” Kidd says. “We got to ski race and we got to do it all over the world. We went to Chile, Europe and Australia.”

Kidd was from Stowe, a small ski town in Vermont, while Sabich hailed from an even smaller town in Kyburz. “We were both from small towns and ski racing took us all over the world,” Kidd says. “It gave us these incredible opportunities.”

The story of Spider Sabich is one of tragedy and untimely death. In fact, tragedy touched the entire Sabich family. Mary Sabich became a physician and died of brain cancer soon after Spider was killed. Steve Sabich died in 2004 of skin cancer.

But for many, including Kidd, to only focus on tragedy skews the fullness of the picture of Spider Sabich.

“I almost never saw a picture of Spider where he wasn’t happy and smiling,” he says.

Kidd doesn’t want his longtime friend to be known simply as the victim of an unfortunate homicide. The grim colors surrounding his death, he says, should be drowned out by the shining brilliance of his life.

Matthew Renda is a Santa Cruz–based writer.

barbara

Posted at 10:06h, 22 MarchMay his soul rest in the peace of God in Heaven.

Suzanne Dwight

Posted at 23:06h, 03 MayI knew Spider in college and he was totally focused on his studies and his ski racing; he was not just a playboy! He told me his parents drove him all over the West to ski races and he wouldn’t be at CU without his ski scholarship , that he HAD to keep his grades up as well as his ski racing. I was so impressed with his maturity for only being 18-19 yrs old!! It seemed like most of the guys were there just to party and drink beer!

Spider lived in the dorm his fresh year ; I don’t believe Billy was his roommate then as Billy was a year older and I never heard Spider mention it..? Not positive tho..

Spiders attitude towards life was amazing! When he broke his leg in soccer practice right before the ‘64 Olympics, I went to visit him in his dorm and when I expressed my sorrow , his response was, with his big smile,“it just ain’t no big thing, Dwight!”

The very next winter before an icy downhill race at Vail, when I expressed concern , he replied, “You can’t get hurt if you don’t fall!’

Nothing got him down!

FYI, Bob Beattie said that on Mar 1,’76, Spider had given Claudine 21 days to move out of his house so he could jumpstart his ski racing ….and he died on March 21st!

Also, Claudine wasn’t divorced from Andy during her relationship with Spider. She even said so in The SF Chronicle. In Feb, ‘76

Claudine should never have gotten away with cold blooded murder like she did ! it was Andy’s money that got her off and

I’m amazed that Billy Kidd is so nonchalant

about his death!

And if it was the accident Claudine claims it was, why wasn’t she at his funeral?

So sad, Spider was so young and had so much to live for! He was special, for sure!

Christine beilharz

Posted at 16:41h, 22 AugustThe French cutie receiving 30 days, what an injustice! we noted previously how Andy stayed by her side. Living in the fast line I am sure distorted their thinking ability. I hate to think Andy would pay off her debt. In the final chapter of this drug infested mess God will do justice. Imagine if God had been in their livess.

Denis J Quilligan Jr

Posted at 02:40h, 17 JanuaryI got to know Spider in the early 1970’s at Hunter Mountain Ski Resort in New York State. I was working with the hugely popular rock band Salvation at the hottest bar on the mountain the Hunter Village Inn. Spider was there representing his sponsor K2 Skis. He was not ski racing because of his injury. During the Pro Ski Races I volunteered to work the races helping to maintain the race course. I was a proficient snow skier and loved the sport. I also volunteered because of the VIP Pass all volunteers earned for working the event.

I approached Spider at one of those VIP events and our conversation quickly became about my band and sure enough Spider was in the audience that evening at the Hunter Village Inn. From that time on we became buddies. Spider loved live music, i loved the ski scene and we were both bachelors. The local rock star and the former champion skier. It was a friendship that we both seemed to enjoy.

When the Pro Ski Championship came to Hunter Mountain in 1976, I was surprised that Spider was not there. When I inquired I was floored to hear that Spider was dead. Shot by his girlfriend. Spider never discussed his personal life. I never kept up on the news. I have to say that I was heartbroken. Our relationship was brief but long enough to know that Spider Sabich was an awesome guy. One who loved life to the fullest. I missed him for sure.

On the subject of Billy Kidd. Billy was all about Billy. He lived for TV cameras and anything that would promote Billy Kidd. I actually believe that he was pleased with Spider’s demise. No more competition. Although Spider could have cared less about being a star. He just wanted to enjoy life and to compete at Pro Skiing again if he could.

MJ

Posted at 10:25h, 05 MarchPeter Brinkman was a close friend of mine back at Heavenly Valley back in that time and Spider was Pete’s friend and partied with us; we had a lot of fun. Spider was a maniac on the ski slopes, loved speed and usually won! I was gone from the area by the time Claudine murdered him but I will never forget the unjustice to Spider over that. It was sad to lose a friend. Peter was also upset by the loss of our friend. RIP, SS.

Martin Seebach

Posted at 08:11h, 04 SeptemberNo nerves running the gates. Watching binding tear loose at last gate and he still placed.

Suzanne Ryan

Posted at 21:18h, 01 AugustWow, interesting comments from people who actually knew him. He sounded like an amazing person. It’s sad when people die from tragic circumstances, because it tends to overshadow who they were and reduce them to their death. Thanks for sharing and look forward to Amy Redford’s 2024/2025 documentary on Spider. (The two friends who posted here should reach out to her team.)