12 Oct Rebels with a Cause

Tahoe’s early generations of snowboarders were instrumental to the sport’s progression long before it hit the mainstream

Snowboarding had a rough childhood. Overshadowed by its older, two-planked cousin, the nascent sport struggled for acceptance in its early years, shunned by a resort industry that wanted nothing to do with the niche phenomenon and its defiant riders.

In Tahoe, however, the sport forged ahead on the periphery of the resort boundaries—or sometimes illegally within—led by bands of young locals with a penchant for outdoor fun.

“We knew we were onto something, and we couldn’t believe the rest of the world wasn’t,” says Damian Sanders, one of snowboarding’s most recognized pioneers, remembered for his wild 1980s hair and high-flying style. “It was so rebellious because the ski resorts would not allow us and we had to sneak onto runs and poach, and that’s what made it so cool. It wasn’t mainstream, and that’s how we liked it.”

Damian Sanders, showcasing his signature bright colors and high-flying style, airs above a

halfpipe on his Avalanche board in 1988, photo by Bud Fawcett, budfawcett.com

Like many of the early snowboarders in the Tahoe area, Sanders grew up skateboarding. Vert riding on ramps and empty swimming pools was all the rage, popularized by professional skaters like Tony Hawk, Steve Caballero, Mike McGill and Lance Mountain, to name a few.

Tahoe bred its own skateboarders. For them, it only made sense to take their talents to the snow. And while the East Coast snowboard campaign—led by Jake Burton Carpenter, founder of Burton Snowboards—was fixated on racing, many of the first Tahoe riders went in a freestyle direction.

“That was in the ’80s when snowboarding was just coming on and skateboarding was huge. Every trick we emulated was from skateboarding, because we didn’t have anybody to follow on a snowboard,” Sanders says.

As snowboarding gained footing, Tahoe became one of its central hubs, with its first wave of riders unwittingly paving the way.

The progression persuaded a few Tahoe-area ski resorts to allow snowboarding starting in the early 1980s. Contests and magazine coverage helped the sport emerge from obscurity by the mid ’80s, which spawned a new generation of riders who stormed onto the scene.

By the late ’80s most resorts—somewhat reluctantly—succumbed to the growing trend, most notably Squaw Valley. Film companies followed suit, documenting the action in Tahoe’s ideal mountain terrain and bringing it into the living rooms of kids across the nation.

“I thought it was pretty awesome,” Tom Day, a professional skier and cinematographer based out of Squaw Valley, says of the early snowboard movement. “It’s always good to see people out sliding on the snow; what you do it on doesn’t really matter. And I think it sparked some interest in people who might have been getting tired of skiing. It kind of revamped them to get back outside.”

A collection of early snowboards owned by Mitzi Sayler Hodges, including two Snurfers, photo by Sylas Wright

The Roots

While others had already experimented with the concept, Sherman Poppen is credited with inventing the modern snowboard. It was Christmas Day 1965 when the Muskegon, Michigan, father nailed together two skis for his kids to slide on like a surfboard. He patented his idea the next year, and the Snurfer was born.

More snowboard companies formed in wake of the creation, including Winterstick in 1969, followed by, among others, Burton, Sims, Barfoot and Avalanche in the late ’70s and early ’80s.

A group of teenaged skateboarding buddies on Tahoe’s North Shore took the relatively new concept to the snow in the late 1970s.

“We all started riding powder in, I’d say, ’78, ’79, ’80. That’s when everybody kind of learned how to turn and do all that stuff,” says Bob Klein, who was friends at North Tahoe High School with fellow skaters and snowboarders Allen Arnbrister, Tom Burt, Mark Anolik and Terry Kidwell, who later earned the moniker “the Father of Freestyle.”

“So that actually means we weren’t really the first wave. We were the first wave of consumers maybe, but not producers… Where we came in was taking the products and pushing the envelope as far as the riding. But that wasn’t really me—I was just the kid with the Wintersticks and I wanted to be part of all the excitement.”

Snowboarding pioneer Bob Klein shows off a couple of his old racing bibs, including one from the 1984 World Snowboarding

Championships at Soda Springs (right hand), photo by Sylas Wright

Tahoe City Halfpipe

Anolik or Kidwell, depending on who recounts the story, discovered in 1979 a natural bowl-shaped feature that became known as the Tahoe City Halfpipe, located near the town dump. Although more of a quarterpipe, with one main hit, it’s considered the first-ever snow halfpipe. Arnbrister and Kidwell frequented the site, Klein says, spending hours shaping the lip with shovels before hitting it.

“Allen was kind of the leader of the pack and he wanted to go there every single day,” Klein says. “I was terrible at the thing. We built this big start ramp and it was pretty gnarly. It was almost vert where you dropped in, and I’m on an old Winterstick with no skag on the bottom, so you had no edge control and it was real sketchy. Most people would lose their balance by the bottom of the transition, and Allen would get pissed off because it would take a long time to smooth it out again and make it right.”

After moving to the North Shore from Vermont in 1983, Keith “Slasher” Kimmel joined Kidwell and Arnbrister as one of the main staples at the Tahoe City Halfpipe, says Klein, who rode there on occasion but spent most of his time hiking for powder turns in the Mount Rose area.

According to Klein, the first sign that their crew was onto something big was when Mike Chantry, a local skateboarder and owner of the Mile High Ramp, showed up to the Tahoe City Halfpipe with Tom Sims and pro skateboarders Steve Caballero and Billy Ruff. While Sims—who founded Sims Skateboards and Sims Snowboards—sponsored Kidwell and Arnbrister on the spot, Klein says he was annoyed by the presence of the non-locals.

“At the time, I wasn’t very nice to him [Sims]. And over the years I was never very nice to him,” says Klein, who later became a sponsored racer for Burton, Sims’ rival. “I had all these different run-ins with him and we ended up having this contentious relationship.

“But before he died [Sims died from cardiac arrest in 2012, at age 61], I totally patched things up and we were friends. And after he died, I also had a lot of introspective epiphanies where I was like, ‘You know, that guy was really cool, actually—a lot cooler than I gave him credit.’”

While Kidwell went on to enjoy a successful snowboarding career, winning multiple halfpipe titles throughout the 1980s, innovating new tricks on the snow—namely the McTwist, first performed by McGill on a skateboard—and receiving the first “kick tail” (twin-tip) pro model, Klein says that Arnbrister went down a darker path of drug use and faded from the scene.

Terry Kidwell, aka the Father of Freestyle, slides a log at Squaw Valley, circa 1991,

photo by Mike Hatchett

South Shore Talent

In 1982, Damian Sanders’ older brother Chris founded Avalanche Snowboards in South Lake Tahoe along with his wife, Bev, and Earl Zeller. The younger Sanders, who was then living in the mountain town of Arnold, California, says he received the first Avalanche board.

“My 13th birthday I asked for a snowboard, and my brother said, ‘Don’t buy one because I’m making one.’ And sure enough, that was the first Avalanche, and he handed it to me on Christmas Eve,” recalls Sanders, who brought the board to his local resort, Bear Valley, the next day and hiked up a hill near the parking lot.

“My brother got me up and gave me a push, and I went about 40 feet without making a turn, then started bouncing turns like a surfer. I probably linked eight to ten turns in a row and I just couldn’t believe it. I was hooked from that moment on.”

Sanders moved in with Chris and Bev his sophomore year of high school, in 1984. By that time he had mastered riding his Avalanche, and he quickly became friends with classmate and fellow ripper Shaun Palmer at South Tahoe High School. The two were on the same level skill-wise, and they spent much of their time riding together at a small resort that once operated on Echo Summit.

Sanders remembers his friend’s unruly ways as a teen—a trait that Palmer unabashedly carried into adulthood.

“He was such a rebel and stoner back then. He lived with his grandma and she was great. It was like a movie, with the bad kid living with grandma and smoking pot all day,” Sanders says, adding that Palmer soon dropped out of high school. “We would terrorize South Lake Tahoe. There was a group of us rebels and we used to just skate all day long, getting chased off properties and trying to find empty pools at hotels and stuff. It was such a good time.”

Klein says Palmer would also hitchhike to the North Shore to link up with the Tahoe City gang. Still a high school–aged teen, Palmer had moved out of his grandma’s house and into a small cabin on his own.

“Because he didn’t have anyone telling him what to do, he would come up all the time and stay with us. My brothers and I were partiers growing up, and I think Shaun felt comfortable there,” says Klein, who later became Palmer’s agent. “We had the Mile High Ramp in Dollar Point, so he’d come up to skate in the summer, and then in the winter he and Damian would come up to Slide Mountain with Chris and Bev.”

From left, Earl Zeller, Damian Sanders, his wife Brandy Sanders and Chris Sanders, photo courtesy

Beverly Sanders

Expanding Their Horizons

Sanders and Palmer also ventured to the North Shore to ride another well-known session spot with Kidwell and company—the Donner Quarterpipe, located off Old Highway 40 near Sugar Bowl.

Many of the early photographs and videos of Sims and Avalanche riders—Kidwell, Kimmel, Sanders, Palmer and others—came out of the Donner Quarterpipe. Included in the early footage is a video shot by Chantry of Kidwell’s first McTwist.

In addition to the Donner Quarterpipe, the riding options had expanded by the early to mid ’80s as a handful of small resorts in the Tahoe area began allowing snowboarding. Among the first resorts to open their doors were Donner Ski Ranch, Soda Springs, Boreal and Slide Mountain (near Mt. Rose).

In 1980, Donner Ski Ranch became the first resort in Tahoe to sell a lift ticket to a snowboarder, according to former owner Norm Sayler.

“I called down to the ticket booth,” which initially refused service, Sayler says, “and I said, ‘Look, it’s 10:30 in the morning, we’ve got four chairlifts running, and at last count we had sold 19 lift tickets. Now that guy has a snowboard in his left hand and a ten-dollar bill in his right hand. I want the ten-dollar bill.’”

Jay Price, former general manager at Boreal, says he was disinclined to allow snowboarders at his resort in the early ’80s, and did so only out of necessity. Ironically, Boreal caters mostly to snowboarders today.

“There was always a problem with them, but we needed to find more outlets for ticket sales,” Price says. “They had the skateboard mentality, with foul language and a grungy look and all that stuff… We would restrict them over to the far side lifts. And now it’s turned out that Boreal is probably the snowboard capital of the Sierra on the percentage of ticket sales.”

Tom Sims competes in the 1985 World Snowboarding Championships at Soda Springs, photo by Bud Fawcett, budfawcett.com

World Snowboarding Championships

In 1983 Sims organized the first official halfpipe competition at Soda Springs as part of the World Snowboarding Championships. The event attracted snowboarders from across the country, including Carpenter and his Burton team. It was chippy from the start.

“There was this big discussion about the overall title, and the Burton riders said—and I was included in this sentiment—‘You can’t include halfpipe in the overall because there’s never been a halfpipe before, and that’s not fair,’” says Klein, explaining that previous events included only slalom and downhill racing.

“It became this contentious thing all weekend. By the time the halfpipe and the overall thing happened, everybody was yelling at each other. It was just kind of funny, because they didn’t have this halfpipe built, and they took the snowcat and pushed up two feet of snow on either side and built the walls and were like, ‘OK, there’s your halfpipe.’ So me and some friends decided that we weren’t going to participate. It was a joke.”

While Soda Springs resident Eddie Hargraves won that first halfpipe contest, Sanders says he went for broke and paid the price.

“I was like this 14-year-old little punk just skying over all these older guys because the landing sucked and they didn’t want to get hurt. But all I cared about was showing off,” Sanders says. “I tried to rotate around a backflip and I ended up in the hospital. I remember waking up and looking around and thinking, ‘Am I in a ski patrol cart?’”

Kidwell won the halfpipe event in 1984 and ’85, then again in ’86 when the World Snowboarding Championships moved to Colorado.

Tom Burt points it down a steep slope on Donner Summit, photo by Aaron Sedway

Magazine Coverage

Although those seminal snowboard contests had their hiccups, they succeeded in attracting media coverage. A Google search unveils video news footage from the 1984 championships, while Thrasher Magazine covered the event in 1985.

The first seasonal magazine dedicated exclusively to snowboarding, Absolutely Radical, hit the shelves in March of ’85 and featured Kimmel on the cover. The publication changed its name to International Snowboard Magazine by its second issue. Two years later, in 1987, TransWorld SNOWboarding debuted.

Other Tahoe snowboarders who appeared in the early magazines included Jim and Bonnie Zellers, who, along with Burt, met in a rock climbing class at University of Nevada, Reno. As opposed to Tahoe’s more freestyle-minded snowboarders, the three Avalanche-sponsored riders were instrumental in taking the sport to the big mountains.

In fact, legendary big-mountain snowboarder Jeremy Jones, who moved to Donner Lake in the early ’90s at age 17, says he fashioned his riding style after Burt and the Zellers.

“They’re really the ones who planted the seed for me,” Jones says. “Tom Burt’s top-to-bottom snowboarding was a whole different level—just his ability to slow down a mountain and come into these critical sections with no hesitation.”

On the other hand, Jones says, he could not identify with the jumping talents of Sanders, who was Burt and the Zellers’ Avalanche teammate: “Damian was just so incredible that it was hard to relate. I couldn’t watch Damian and be like, ‘I’m going to go chuck 50-foot backflips when I get out to California.’ Damian was just chucking at a ridiculous level. But I was like, ‘I can never do that.’ And I never have.”

Bonnie Zellers says she and Jim (who married in 1992) and Burt milked the magazines’ support to travel to big-mountain locations outside of Tahoe. As a result, the three are known for bagging multiple first descents around the globe.

“We did the competitions like halfpipe and whatnot for awhile, but we kind of moved out of that and more into our passion, which was backcountry,” Bonnie says. “We would sell stories to the magazines, and then they would pay for all our travel, which was kind of our intent.”

Mike Jacoby hits a quarterpipe at Donner Ski Ranch, circa 1994, photo courtesy

Mitzi Sayler Hodges

The Second Wave and Squaw Valley

By the time magazines began showcasing the sport in the mid to late ’80s, a new group of snowboarders were vying for recognition in Tahoe—names like Noah Salasnek, Chris and Monty Roach, Mike and Tina Basich, Dave Hatchett, Dave Seoane, Steve Graham, Tucker Fransen and others.

Burt says the “second wave” of riders, many of them from the Bay Area and Grass Valley, came in with a “newer-kid skate style” that impressed him.

“Chris Roach was always super strong, and Noah also had great style. He was an incredible rider to watch,” Burt says of Salasnek, who also left his mark with some of the most progressive big-mountain riding of the time. “There are always riders whose style you wanted to emulate, and Noah was one of those riders.”

Noah Salasnek, pictured at Boreal, was among the biggest names to come out of Tahoe,

photo by Aaron Sedway

After years of being restricted to the backcountry and a handful of smaller resorts, Tahoe’s riding scene received a shot in the arm the spring of 1987 when Squaw Valley allowed snowboarding on a trial basis for the remainder of the season. The next season Squaw officially opened to snowboarding.

Mike Hatchett, co-founder of Standard Films, put the resort’s opening in perspective: “It’s probably hard for a lot of kids to imagine now, but imagine having a snowboard and that’s all you ever did, and you couldn’t ride Squaw. When Squaw opened, that kind of blew open the doors at that point. It was game on.”

Adds Sanders: “Squaw was the game-changer that we were waiting for for years. It was kind of a shame because all those small resorts that did risk their neck for us, we kind of just abandoned them as soon as Squaw opened. You didn’t want to go back to Boreal if you could ride Squaw all day.”

Jerry Dugan was among the first to capitalize on the Squaw opening.

Dugan pointed a video camera at his friends ripping around Squaw—Sanders, Graham, Seoane, Salasnek and others—and turned the footage into The Western Front, one of the first snowboard movies produced.

“Everyone dug it. No one had really done anything like that,” says Dugan, who partnered with Arthur Krehbiel to form Fall Line Films. “Burton and Sims had done one video apiece that was just a team video. But our video was the first in that genre where it was like, ‘Hey, look, there’s a Burton rider and a Sims rider and a Look rider, all these different guys.’ And so it took off in Northern California because they were all Nor Cal boys.”

This photo of Nick Perata in the early snowboard years at Squaw Valley was the cover of Fusion

Films’ Totally Board, photo by Mike Hatchett

Video Takeover

While Dugan says The Western Front sold a few thousand copies, the next video by Fall Line Films, Snowboarders in Exile (1990), reached a significantly larger audience, and showcased the sport’s rapid progression at the time.

“It was such a difference between The Western Front and Snowboarders in Exile. It was absolutely incredible. All of a sudden we were doing real lines, jumping cliffs, doing big-mountain stuff—the same stuff they were doing in Blizzard of Aahhh’s,” Dugan says, comparing the video to Greg Stump’s 1988 extreme skiing movie. “We might not have been as technically proficient, but we had Tom Burt and Jim Zellers, who were like big-mountain technicians, and Damian Sanders, who was jumping off as big of jumps as [Glen] Plake and those guys.”

Twin brothers Mike and Dave Hatchett, as well as Mike McEntire of Mack Dawg Productions, also got in on the early video scene based in Tahoe. The three collaborated to create Standard Films, which released TB2—A New Way of Thinking (1993), TB3—Coming Down the Mountain (1994) and TB4—Run to the Hills (1995). After TB4, Mack Dawg Productions ventured back out on its own as the Hatchett brothers continued the TB series.

The Hatchetts had previously teamed up with Pat Solomon, Shawn Farmer and Nick Perata to produce Totally Board (1991) under the name Fusion Films, while Mike Hatchett also worked with Fall Line Films on two movies, Critical Condition (1991) and Riders on the Storm (1992).

Despite the fact that Tahoe’s big three film companies were in direct competition, their owners remained friends and all enjoyed their share of success.

Those early videos also inspired future generations of snowboarders while catapulting the riders into the international spotlight. Farmer carved out his place in snowboarding history with standout segments during Tahoe’s budding film industry, as did other big-name riders such as Salasnek, Burt, Terje Haakonsen, Jim Rippey and Johan Olofsson, to name just a few.

Jim Rippey soars above a halfpipe at Squaw Valley, photo by Aaron Sedway

“The rock stars to us were the guys who were in those first videos,” says Rippey, who moved to Tahoe during the 1989–90 winter. “Basically you watched those videos over and over and over again. Those were the influences.”

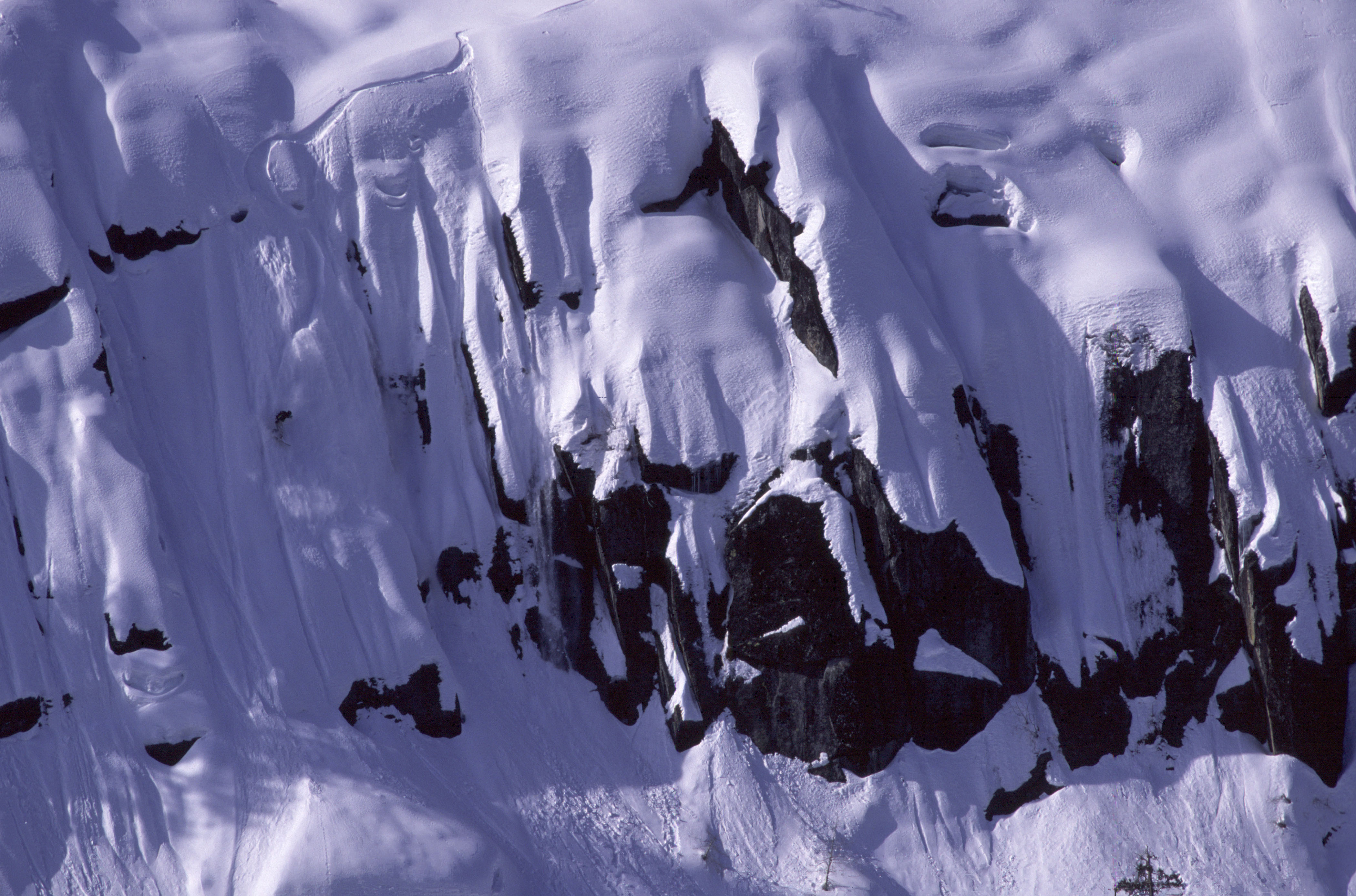

Although the film companies shot a fair amount of footage inbounds at Squaw Valley, they took advantage of Tahoe’s array of easily accessible backcountry as well. Common filming locations included areas around Donner Summit, Mount Rose and Tahoe’s West Shore, while iconic sessions went down on specific features dubbed the I-80 drop, Hero Gap, the Johan Kicker, the Western Front Wind Lip, the Mount Rose Onion Roll and Grizzly Spines—a bony, no-fall line in Blackwood Canyon that Jones rode with precision for Standard Films.

Tahoe’s snowboarders and film companies also progressed the sport well beyond their home mountains. Jones, who at age 41 is still pushing the limits of big-mountain riding, points to Salasnek’s famous descent in TB5 on Alaska’s Super Spines as an example. Other standout first descents by Tahoe riders in Alaska include Dave Hatchett on Mendenhall Towers in TB3, Burt on Cordova Peak in TB6—Carpe Diem and Rippey on Sphinx, also on TB6.

“It was amazing the impact that Tahoe had on Alaska, and really the Standard Films scene was one of the main leaders in evolution up there,” says Jones. “There was so much evolution in the mid ’90s up in Alaska, and it was these guys from Tahoe who really were at the center of that.”

Jeremy Jones tackles Grizzly Spines in Blackwood Canyon on the set of Standard Films’

Paradox, photo by Aaron Sedway

Looking Back

Simply put, Tahoe was the place to be in the early days of snowboarding. The scenic nook of the Sierra was like a perfectly blended cocktail with all the right ingredients—snow and sun, expert terrain, media exposure and, most importantly, talent.

“Somehow, back then, we all knew where to be and when before cell phones. And once we were together, it was like the rat pack terrorizing,” says Sanders, whose snowboarding career wound down in the early ’90s as the result of multiple knee injuries.

“We had a group of like 15 guys and about 10 were pros who ripped. So we would just find jumps and try to outdo each other. It doesn’t seem like it happens like that anymore. But Tahoe was such a mecca. It was awesome.”

Dugan credits the laid-back California vibe and embedded snow, surf and skate culture for snowboarding’s rise in popularity in Tahoe. Jones says it was the contests, media and proximity to the ocean that drew him to Tahoe—but it’s the snow that’s kept him here.

“I love the snowpack. It’s much less complex than other places. It’s a great snowpack to grow old in,” he says.

Jeremy Jones shreds a line near Echo Summit, photo by Aaron Sedway

While snowboarding’s popularity eventually plateaued as a result of a resurgent ski industry, its rich history in Tahoe is still celebrated by those who were at the forefront. Throwback events such as the Tom Sims Retro World Championships and Legends of Snowboarding take place annually at the resorts that first embraced the sport, bringing the old-school riders out of the woodwork for a day of reminiscing and fun.

“When I’m around and get to do them, they’re a blast,” says Burt, who still shreds the Tahoe backcountry when not judging on the Freeride World Tour. “It’s always fun to see everybody and ride the old equipment.”

Tom Day, who worked with Standard Films throughout the ’90s and is now a cinematographer with Warren Miller Entertainment, says he’ll forever cherish his involvement with snowboarding’s influential early years in Tahoe.

“There was a lot of good energy back then and a lot of great talent,” he says. “I wasn’t there at the very beginning, but I was there pretty close to the beginning of the whole snowboard boom. It was a good industry to be a part of. There were a lot of go-getters. I’m honored to have been a part of that, for sure.”

Tahoe Quarterly editor Sylas Wright tried unsuccessfully to emulate Tahoe’s early professional snowboarders as an aspiring teen.

Shaun Palmer launches high above a halfpipe at Sierra-at-Tahoe, photo by Aaron Sedway

Not all of Tahoe’s early snowboarders were big-name pros. Here, Chris Talbot gets rad near Mount Rose, circa 1983, photo by Tim (TMVK) Miller

Chris Talbot, Jim Hays and Brian Lambert take a beer break between runs, circa mid ’80s, photo by Darin Talbot

No Comments