10 Oct The Legend of White Wolf

Troy Caldwell, the enigmatic landowner between Squaw and Alpine, talks past dealings, legal battles and future plans

He was a man out of his element.

Far away from his native habitat of the Sierra Nevada, Troy Caldwell was navigating the throngs along Market Street in downtown San Francisco in what used to be called his Sunday best. He entered the office of the Southern Pacific Land Company in time for the meeting that would lead ineluctably to his current position—as an enigmatic presence that has bedeviled the Tahoe ski industry for years.

“I’m in my best Tahoe clothes, if you know what I mean,” Caldwell says when recalling that fateful morning in 1988.

“Then I walk through these 19-foot-high chrome doors and I am thinking, ‘Oh my God. I am totally out of my league.’”

Ski Bum at Heart

Caldwell is not a businessman, nor a real estate baron, nor is he particularly interested in aspiring to either of these positions. Instead, he has more than a fair share of ski bum in his character, more intent on sustaining the mountain lifestyle than making a pile.

After growing up in the Bay Area, Caldwell attended school in Cupertino before spending stints in Fresno and Northern California. But it was the Truckee-Tahoe nook of the Northern Sierra that functioned as his lodestar.

“I’ve lived in Tahoe most of my life,” Caldwell says. “Once I got hooked up with this place it swallowed me up and I haven’t left.”

Actually, it was Caldwell’s search for a way to stay and make it in the Tahoe region that led him to Southern Pacific Land Company. In 1969, he was 19 years old and intent on developing himself into a world-class skier. Finding the ski-racing market saturated, Caldwell got involved in the nascent world of freestyle skiing and for a while was considered one of the best around, earning a sponsorship from Alpine Meadows and hitting the pro circuit.

After he wound down his career in 1974, Caldwell began the practice of picking up property in the Truckee-Tahoe area, building small ski cabins and then selling them, often earning a modest return on the investment.

Around the mid 1980s, Caldwell and his wife, Sue, started shopping for property in proximity to their favorite resort, Alpine Meadows (Sue was a longtime employee of the resort).

Their tentative plan was to procure a five-acre parcel, build a ski lodge–style bed-and-breakfast on the property and have Caldwell take guests out skiing on the hill during the winter—a little upscale private resort modeled after the Stein Eriksen Lodge in Park City, Utah.

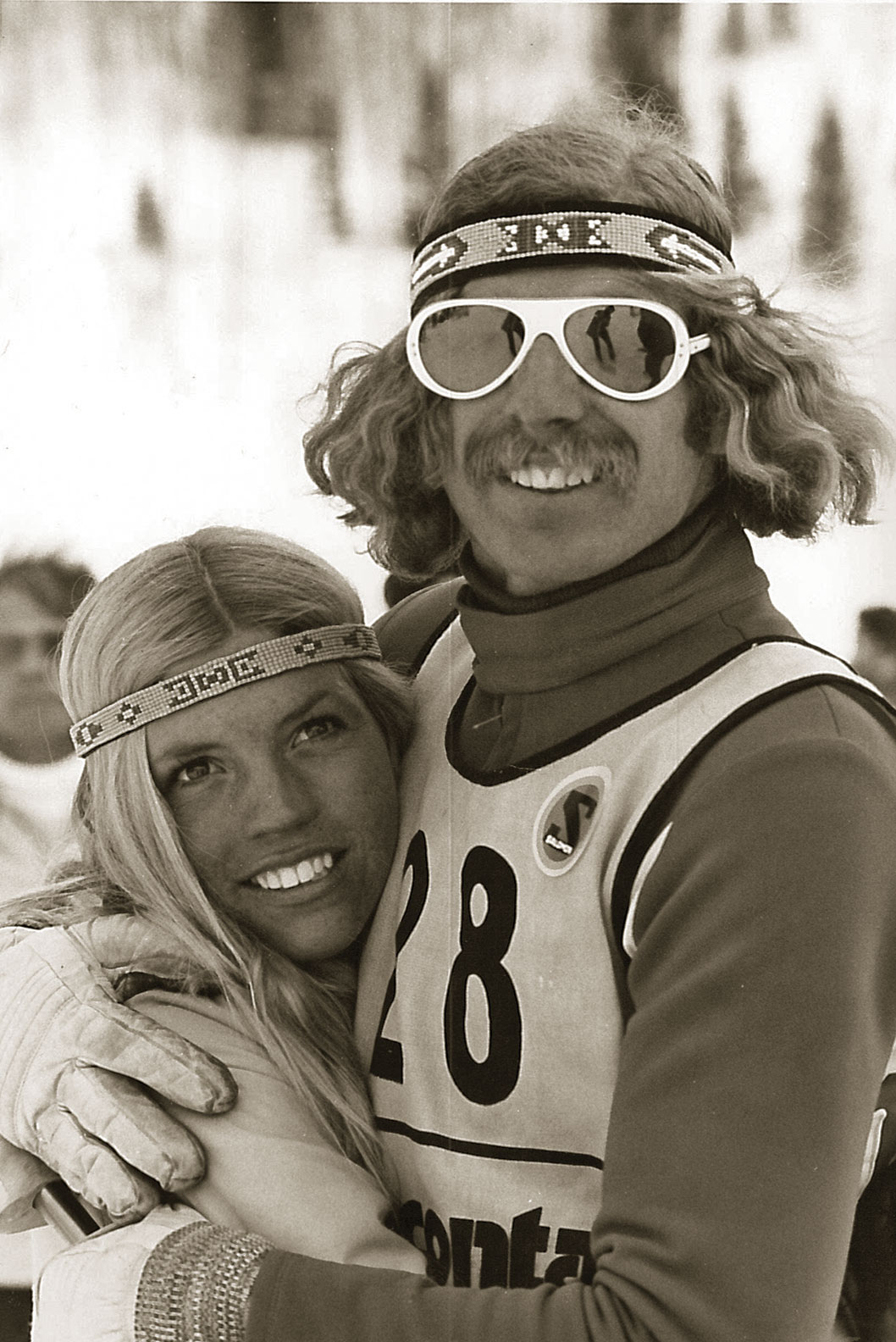

Troy Caldwell and his wife, Sue, smile for the camera at the Pecante Cup in Park City,

Utah, circa 1974, courtesy photo

Fortunate Find

Caldwell noticed a little sliver of property off the north side of Alpine Meadows Road owned by the railroad since the mid nineteenth century. Intent on scooping it up, he put on his Tahoe best and ventured to the plush San Francisco offices of the Southern Pacific Land Company. There, Caldwell met with Brandon Mark, a representative of the railroad giant’s land division, who was looking debonair in an elegantly cut three-piece suit.

Caldwell informed Mark of his designs and was told that he was out of luck because the railroad land subsidiary was unable to subdivide the property, so the five-acre parcel was no dice. On the other hand, if he wanted all 160 acres, it was his lucky day.

Caldwell doubted he could afford that much land. However, Southern Pacific was attempting to cement a deal with a real estate company in Southern California called Catellus, and any property the railroad company could get off its hands before the deal went through amounted to a windfall for all the stockholders. So the property could be had on the cheap.

Still, Mark came back with more bad news.

The property wasn’t 160 acres. It was 460 acres and consisted of rugged, steep, granitic terrain. But the good news was the property included the top of KT-22, the iconic mountain and corresponding chairlift that affords access to some of the best expert terrain in North America.

Squaw Valley had rented the land from the railroad and paid an undisclosed amount per year, so Caldwell could start making money on that investment from the get.

Caldwell was in. But the story gets juicier.

“Unbeknownst to me, ‘cause I am naïve at the time, Southern Land Pacific starts shopping the piece of property and they call up Squaw Valley,” Caldwell says.

The way Caldwell tells it is that Southern Pacific contacted an accountant in the Squaw Valley business office and offered the property. Without consulting then-Squaw Valley owner Alex Cushing, who no doubt would’ve jumped at the opportunity to own the land outright, the accountant told Southern Pacific that Squaw rented the land cheap, so they were not interested.

“Squaw Valley says yes and it’s the end of this story,” Caldwell says. “So the door opened for me.”

Caldwell bought the property and thus became the man in the middle, the little guy who holds sway over ski industry titans and the man who currently owns the property between two resorts owned by the same company that are desperately trying to connect.

With no roads, power or sewer, the Caldwells spent the early years relying on their trusty old

bulldozer as the main transportation, courtesy photo

Battling a Giant

“You know, a lot of people say Troy is the luckiest guy in the world,” says Jennifer Pizzi, a friend and business associate of Caldwell’s. “But I don’t know, he has had to deal with a lot of bull—-.”

Complications began after Caldwell officially gained possession of the property in 1989. He abandoned the bed-and-breakfast idea and began to think bigger.

“We talked to Four Seasons, and thought about other specialized hotel complexers,” Caldwell says. “We talked to the high-end portion of the world just sorting out our options.”

But Caldwell says he also knew that to be in his position meant he had to think about being a part of the ski industry.

“That’s the real reason to be in this neck of the woods,” Caldwell says.

None of this ambition was lost on Cushing, who undoubtedly noticed he was making his rent checks out to a different owner who had designs to build his own ski resort.

In the 1990s, Caldwell and Cushing had a few preliminary meetings and discussed renegotiating the lease for KT-22. Caldwell not only owned the famed summit, he also owned about 70 acres of property on which Squaw ran part of its resort.

Talks broke down in 1995, when Cushing sued Caldwell in Placer County Superior Court, claiming he had overpaid on the lease for some years. The suit dragged on for a couple years until he and Caldwell reached a settlement, which was complicated but in essence was an old-fashioned barter.

Caldwell would cede Squaw Valley the KT-22 property if Squaw gave Caldwell the Headwall chairlift, which at the time was three years old. Not only that, but Squaw had to install the lift on Caldwell’s property so he could finally achieve his dream of opening a private ski resort called White Wolf Mountain.

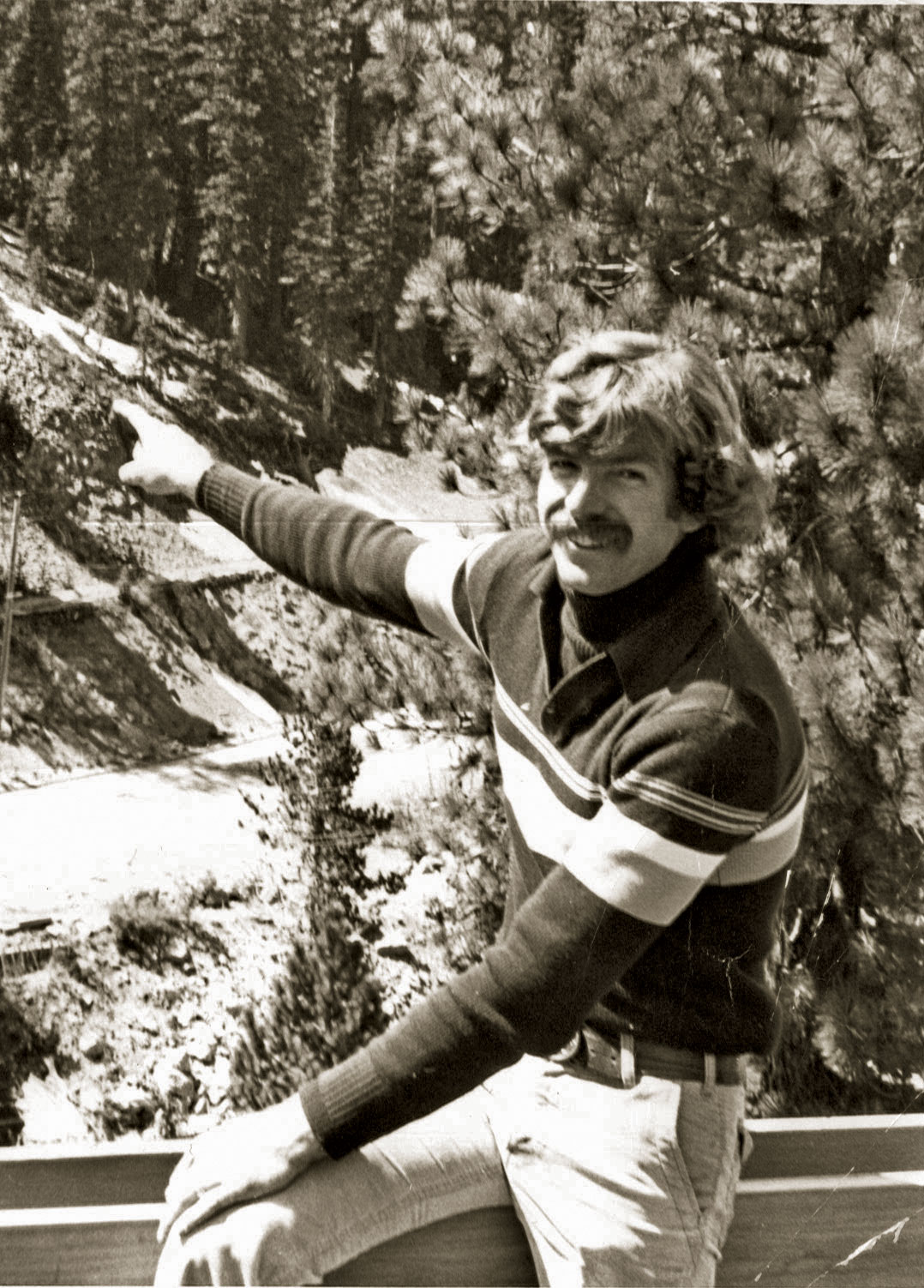

A youthful Troy Caldwell proudly gestures to the progress of the first dirt road on White Wolf,

circa early ‘90s, courtesy photo

The settlement was hammered out in 1997, but soon Squaw backed out, according to Caldwell, and tried to give him a 30-year-old lift instead of Headwall.

Pizzi says she thinks it was all an attempt by Cushing and Squaw Valley, which was well-heeled, to drag Caldwell, who didn’t have much capital, through the courts and “bleed him dry.”

Caldwell acknowledges the court cases took their financial toll.

“Squaw figured out that if they wanted that piece of property, they could spend money dragging me through a courtroom,” Caldwell says. “For a while, I didn’t know if we could fight a giant corporation, but we did it.”

That’s the thing about Caldwell—he is tussling with some heavyweights in the ski industry, but he is the little guy, at least in terms of funds.

“When I first met Troy I thought he was going to be this angry hermit or this rich guy who inherited family money and bought a mountain,” Pizzi says. “But he’s neither of those. That’s what makes it so fascinating. He’s just a sweet guy who found himself in the middle of all this.”

Caldwell began installing a 17-tower chairlift on his property in 2005, courtesy photo

White Wolf Mountain

What Caldwell lacks in funding, he compensates for with an adamant approach to his vision. He wants White Wolf Mountain to become a reality and he’s not going to sell the property for what would likely be a lucrative profit and move on. He’s dug in. He and his wife have built a modest house on the property and Caldwell has a dream.

In 2000, Caldwell obtained a permit from Placer County to install a chairlift—which resulted in the Bear Creek Homeowners Association, a powerful entity in the Alpine Meadows valley dating back to the creation of the resort in the 1960s, suing the county for issuing the permit. Despite having to defend the county in the suit, Caldwell began installing the 17-tower lift in 2005 with the help of an engineer, contractors and about 30 on-and-off volunteers. Because the permit prohibited heavy industrial equipment, Caldwell used a helicopter to install sections of the lift.

“It’s just been hanging ever since,” says Caldwell, adding that the lift is almost ready to spin. All it needs is a cable and chairs and some finish work on the terminal building at the base.

Now, however, Caldwell has bigger plans. He is in the process of developing a 38-home private residential community that will have access to two chairlifts leading to terrain that Tahoe skiers have coveted for years.

Caldwell, who is as interested in architecture as he is skiing, waxes exuberant when he discusses the project.

“These buildings are going to be old-world rock on the outside, with the new modern black glass look,” Caldwell says. “I thought about going with the old Tahoe log cabin type of feel, but in order to step into new technology like solar capturing you need to go with the new Tahoe feel.”

Caldwell is cognizant that the exclusivity part of the project may rankle some, but in discussions with the Alpine Meadows community, his neighbors did not want the additional traffic associated with an 800-unit complex.

“To keep the numbers low in that amount of space I had to go super high-end on this thing,” Caldwell says.

White Wolf Mountain, Caldwell’s longtime dream, is close to materializing. However, he still needs to go through the approval process with Placer County, performing environmental analysis and fighting the inevitable fights that occur when any development is undertaken in the Truckee-Tahoe region.

Caldwell enjoys a spring afternoon skiing in his own backyard, April 2016, photo by Cole Wilford @c.willy

Amicable at Last

In the meantime, Caldwell’s relationship with Squaw has gone from litigious and acrimonious to collegial, even fraternal.

The difference is KSL Capital’s purchase of Squaw in 2010 and subsequent purchase of Alpine Meadows in 2011. The merger of these two resorts cast a new urgency on plans to connect the resorts via a gondola that had long been in the gestation process.

Of course, any discussion about the construction of such an apparatus would necessarily include the man in the middle.

Caldwell says the gondola will happen.

“We came to an agreement where we could locate it and still keep the privacy for the development on our side,” Caldwell says.

Caldwell still owns the top of KT-22, but sources close to the situation say the lease has been renegotiated and Caldwell and Squaw have agreed on a leasing arrangement of property on which to build a portion of the gondola in the new agreement.

Caldwell says a large difference in his newfound amicable business relationship with his neighbors is CEO of Squaw Valley Ski Holdings Andy Wirth.

“Andy has totally treated me like solid gold,” he says. “We don’t look for the solutions to our problems in the courtroom. And we have similar goals to accomplish.”

Caldwell poses with the newest member of his family, Foster, in August 2015, courtesy photo

Wirth confirmed the gondola is “all systems go” as his company works with Placer County, the U.S. Forest Service, Caldwell and others to get the process started. Because the project will involve county, state and federal jurisdictions, Squaw will have to conduct environmental analysis mandated by the California Environmental Quality Act and the National Environmental Protection Act.

The gondola project is separate from the controversial Squaw redevelopment plan that continues to move through the approval process at Placer County.

While those impediments remain, Wirth says working with Caldwell thus far has been simple and straightforward. “Listen, we’re both mountain guys and skiers,” Wirth says. “It’s true the previous owners didn’t work with Troy, but I’ve found him to be a straight-up fella. He’s got a deep and caring heart and it extends to the whole community.”

For Pizzi, that’s what fascinates about Caldwell’s tale. He’s far from the “Don’t Tread On Me” property rights fanatic you might envision. He’s also not some business maven who buys up property in the mountains so he can lean on ski resorts with inimitable leverage.

He’s a guy who loves Tahoe and stumbled upon one of the most important parcels in the Tahoe area, if not the entire Sierra, and he’s formulated the same granitic hardness when it comes to his right to achieve his vision for his property.

“He wants nothing more than to contribute to the ski industry,” Pizzi says, “because it’s been so good to him.”

Matthew Renda is a Santa Cruz–based writer.

tom boxler

Posted at 15:38h, 27 DecemberAndy Wirth is now gone!