01 Oct Crossing Paths with History

A backcountry snowboarding adventure into the Great Western Divide

Mileage smileage. This is one of those High Sierra adventures where it’s better not to know exactly how far we’re trying to go. Distances and elevations spinning in our heads might only distract from our confidence. The only things that matter are dialed in. Weather is stellar, we got the gear, we got the gusto and we’re in prime launch position. Time to finally climb Mount Brewer.

This pep talk floats through my brain as I curl up in my sleeping bag and try to fall asleep. It’s a crisp March night and I am snow camping deep in Kings Canyon National Park with my wife Allison and fellow splitboarder Nick Russell. We toured in to this camp spot two days earlier from Onion Valley, a trailhead 15 miles west of Independence on Highway 395. We hauled in enough food to camp five nights with the goal of snowboarding off the top of a couple epic Southern Sierra summits.

That day we had climbed Mount Rixford, a nearly 13,000-foot peak that offers expansive views of the Kings Canyon high country. From Rixford’s summit, we could see hundreds of peaks. Layer after layer of towering spires and craggy ridges spread out from our perch in every direction. Among all the mountains on the horizon, an enormous pyramid-shaped rock face to the southwest dominated the skyline. This granite monster, flanked by huge snowfields, was the mighty Mount Brewer.

Nick Russell puts a name to a face identifying peaks in Kings Canyon National Park, photo by Seth Lightcap

Nick Russell puts a name to a face identifying peaks in Kings Canyon National Park, photo by Seth Lightcap

King of the Great Western Divide

Standing at 13,570 feet, Mount Brewer is not one of the tallest peaks in the Sierra. Brewer’s proud prominence lies in the mountain’s unique position in the heart of the range. Brewer is the northern high point of the Great Western Divide, a gigantic ridge that stretches just west of the true Sierra Crest. The divide runs north–south for 42 miles, forming the division between the Kaweah, Kern and Kings river watersheds. Mount Brewer sits on the far north end of the divide and stands out as the crown king of this massive escarpment of granite.

Mount Brewer’s auspicious position in the range has attracted the eyes of Sierra explorers for over 150 years. The story of Mount Brewer’s first ascent represents the first chapter in the history of High Sierra mountaineering.

In 1860, Harvard geology professor Josiah Whitney was tasked with leading the first official geological survey of California. The purpose of the survey was to map the state, while also taking note of the natural history of the land. Whitney appointed an aspiring botany professor from New York named William H. Brewer to lead the California survey field party.

From 1860 to 1864, Brewer and a small crew traveled up and down the state climbing every hill they could find to gain perspective of the surrounding topography. By the spring of 1864, Brewer had traveled over 14,000 miles from Mount Shasta to Los Angeles in his quest to map the state. One of the only regions he had yet to explore was the highest reaches of the Southern Sierra, the area that is now Sequoia and Kings Canyon national parks.

At that time, no man had ever stepped foot in this rugged region of the Sierra. Not even the Indians had attempted to cross this seemingly impenetrable wall of mountains. Determined to begin mapping this unexplored zone, Brewer planned an expedition to the area starting from the town of Visalia in May 1864.

Stretching out at camp, Allison Lightcap prepares for the next day’s push, photo by Seth Lightcap

Stretching out at camp, Allison Lightcap prepares for the next day’s push, photo by Seth Lightcap

Shattering the Sierra Paradigm

Brewer and his crew took five weeks to walk within striking distance of the Great Western Divide. Along the journey, Brewer spent days staring at the ridge and the gorgeous pyramid-shaped peak that marked its high point. He surmised the peak might be the highest mountain in the range. By his estimation, the snow-capped ridge before him was the Sierra Crest and to the east of the ridge the Owens Valley.

On July 2, Brewer and his topographer, Charles Hoffman, succeeded in climbing the stunning peak that had entranced their gaze for so long. Upon reaching the summit and looking off to the east, their jaws hit the talus. Brewer and Hoffman stared dumbfounded at a jumbled mass of still higher peaks to the east. Their speculation about the position and elevation of the Sierra Crest had been dead wrong. They spent the next two hours on the summit sketching the eastern skyline while taking elevation measurements with a barometer.

Later that month, Brewer detailed this paradigm-shifting view writing in his journal:

“The view was yet wilder than we have ever seen before. We were not on the highest peak, although we were a thousand feet higher than we anticipated any peaks were. We had not supposed there were any over 12,000 or 12,500 feet, while we were actually up over 13,600 feet, and there were a dozen peaks in sight beyond as high or higher! Such a landscape! A hundred peaks in sight over thirteen thousand feet, deep canyons, cliffs in every direction almost rivaling Yosemite, sharp ridges almost inaccessible to man, on which human foot has never trod—all combined to produce a view the sublimity of which is rarely equaled, one which few are privileged to behold.”

Returning to camp that night, Brewer and Hoffman described the groundbreaking views they gained that day to Clarence King, Dick Cotter and James Gardiner, the three other members of the survey party, who had stayed behind to watch camp. Soaking in the news of the day, the men immediately proposed naming the peak Brewer.

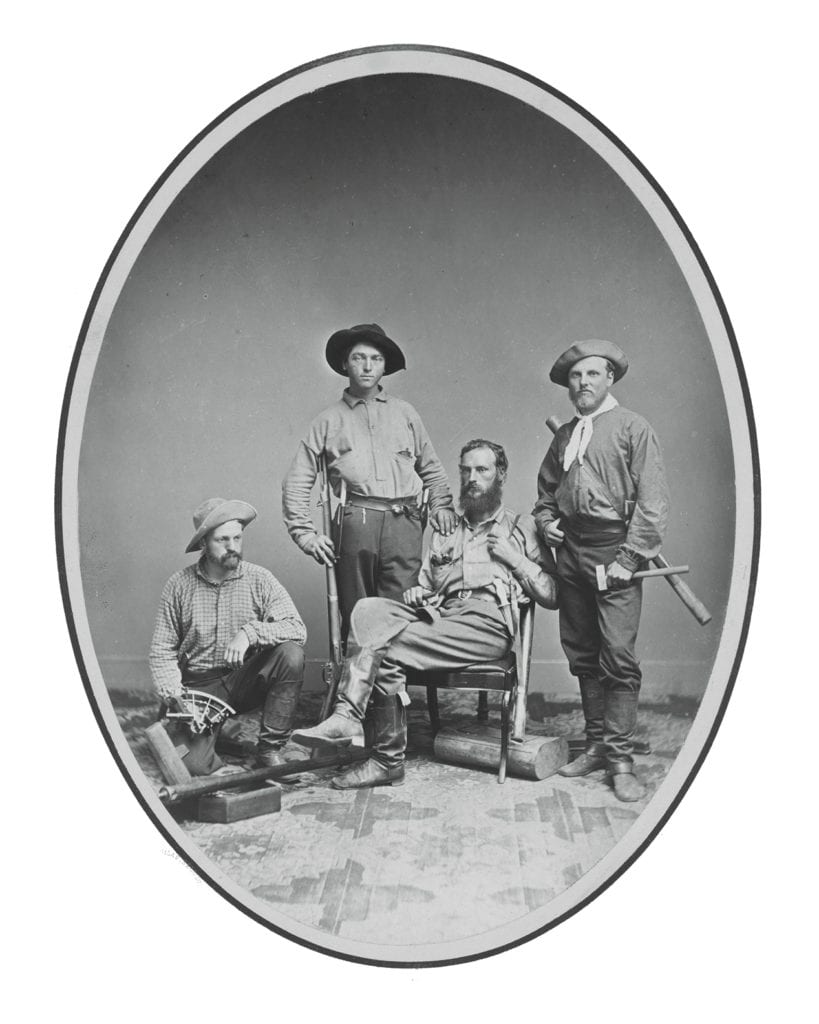

James Gardiner, Richard Cotter, William Brewer and Clarence King, 1864, photo by Silas Selleck, 1864, Albumen silver print, National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution

Climbing Into the Unknown

Despite his young age of 22, King was the strongest explorer of the group and the most motivated mountaineer. The day after hearing Brewer’s description of the treacherously high peaks to the east, King requested permission to venture out even deeper into the range with Cotter to make an attempt at climbing the highest peak they could find. After some consideration, Brewer consented.

Two days later, all five men climbed back up to Mount Brewer’s ridge to see King and Cotter off. Also an eloquent writer, King later described his awe upon looking off the ridge in his famous book, Mountaineering in the Sierra Nevada, published in 1872.

“Rising on the other side, cliff above cliff, precipice piled upon precipice, rock over rock, up against the sky, towered the most gigantic mountain-wall in America, culminating in a noble pile of Gothic-finished granite and enamel-like snow. How grand and inviting looked its white form, its untrodden, unknown crest, so high and pure in the strong blue! I looked at it as one contemplating the purpose of his life; and for just one moment I would have rather liked to dodge that purpose, or to have waited, or have found some excellent reason why I might not go; but all this quickly vanished, leaving a cheerful resolve to go ahead.”

Leaving the others to take more elevation measurements on Mount Brewer, King and Cotter pushed deeper into the mountains for the next five days. They ended up crossing over the Great Western Divide and climbing a 14,025-foot peak they named Mount Tyndall. From the top of Tyndall they correctly identified the highest mountain in the Sierra and named the peak Mount Whitney in honor of the survey party’s official leader, Professor Whitney.

After one unsuccessful attempt to climb Mount Whitney, King and Cotter returned to camp to meet the survey crew. By this point the crew was running out of food and headed back to civilization to report their findings.

The survey crew’s ascents of Mount Brewer and Mount Tyndall stand as the first major achievements in the history of High Sierra mountaineering. The fifth-class routes King and Cotter established crossing over the divide also set a new high bar for technical climbing in the Sierra. Brewer noted in his journal that he did not think their bold alpine exploits would be repeated again anytime soon.

“It is not at all probable that any man has been on the top before, or ever will be again—for a long time at least. There is nothing but love for adventure to prompt it after we have the geography of the region described.”

Brewer’s assessment was spot-on. Over the next 30 years, only one other man climbed Mount Brewer. Even to this day, one must hold a deep “love for adventure” to reach the summit. Mount Brewer is rarely climbed because of the long approach. In summer, the shortest route to the summit is a 15-mile trek that climbs 8,500 feet. In winter, the peak is even less accessible, requiring a nearly 20-mile trek and over 10,000 feet of climbing. Every slope on Mount Brewer is a backcountry skier’s dream, but very few winter explorers even attempt, let alone succeed, in shredding off the summit each year.

Allison Lightcap rolls off the summit of Mount Rixford, photo by Seth Lightcap

Allison Lightcap rolls off the summit of Mount Rixford, photo by Seth Lightcap

Nothin’ to it but to do it

Gaping at Mount Brewer from Mount Rixford that day seals the deal for us. The slopes cascading off Brewer’s east face are plastered with snow, as are the drainages that lead up to Brewer’s base. The deep snow means high-country travel conditions are prime with fast route-finding on the way up and easy riding on the way down.

The mountain gods are smiling on us. Before dropping in for our snowboard descent off Rixford, we accept their offer, deciding to make a go for Mount Brewer the next day.

The “digi-ping” of my watch alarm wakes me at 5 a.m. It’s still pitch dark and cold, but it’s go time. If we have any chance at all, we need to be moving at first light.

My self pep talk the night before reflects the tinge of audacity in our day’s plan. I avoid adding up the miles because I know it will sound ludicrous. There’s little chance we can make it to Brewer and back within daylight hours, and there’s strong potential that we climb all day and still come up short.

Cold, dark-thirty breakfast is no time to serve up a hot, steamy buzzkill though. But while gathering our gear, I do ask Allison and Nick if they have fresh batteries in their headlamps.

It’s light enough to see just before 6 a.m. We begin our day’s adventure by descending 1,000 feet to the Bubbs Creek drainage below our camp. Snowboarding down the still frozen face goes quickly and soon we are touring down the valley past massive old-growth trees. When the valley steepens, we flip our splitboards to ride mode and descend past a raging waterfall. Just before 9 a.m. we arrive in Junction Meadows, a confluence of two major creeks at 8,100 feet. We cross the creeks on fallen trees and head south, taking turns breaking trail up the East Creek drainage through the softening spring snow.

Climbing up East Creek, we are now in the valley that the California survey crew looked down upon from Mount Brewer. Massive granite walls line the valley on both sides with the Great Western Divide looming large above us. At 1 p.m. we stop for a quick lunch near the base of Brewer’s east ridge. We estimate it will take us two hours to gain the notch in the ridge that accesses Brewer’s south face and likely two hours more to climb to the summit from the notch.

Climbing to the notch demands a steep bootpack, but the snow is soft and the climbing relatively easy. From the notch we climb down a couple hundred feet of broken granite to regain the snow on the south face. The summit is now less than 1,000 feet above us.

Moving nonstop for 10 hours, our pace slows as we climb through the thin air at 13,000 feet. Climbing the last 500 feet takes us nearly an hour. At 5 p.m., with clouds now swirling in around us, we finally reach the summit.

Nick Russell drops in from the summit of Mount Brewer, photo by Seth Lightcap

Nick Russell drops in from the summit of Mount Brewer, photo by Seth Lightcap

High-fives and a few deep breaths are all we have time for on the summit. The snow is still soft but it’s starting to refreeze. Within 15 minutes we are strapped into our boards ready to drop in.

Our descent is breathtaking as we rip down the south face staring out into the deepest reaches of the Sierra. Steep turns dropping through a notch lead to a stunning wind-sculpted snow wave that we slash down for nearly a mile. Three hours after leaving the summit, we arrive back at Junction Meadow having descended just shy of 6,000 feet.

We click on the headlamps and retrace our steps across the fallen logs over the creeks. We don’t need the headlamps for long. As we begin the trek back up the Bubbs Creek drainage, a full moon rises over the horizon. For the next two hours we climb up through the forest back to camp under ethereal moonshine.

Eighteen hours after crawling out of our sleeping bags, we collapse back into them. Our legs are rubber and our feet blistered, but all we feel is the warm satisfaction of improbable success. The struggle was worth every step to cross paths with history and sit on the throne of the Great Western Divide.

Seth Lightcap is a Truckee-based writer, photographer and avid explorer of Sierra rock, snow and trail. See more of his stories at www.sethlightcap.com.

Still three hours from camp, Allison and Nick catch last light on Mount Bago, photo by Seth Lightcap

Still three hours from camp, Allison and Nick catch last light on Mount Bago, photo by Seth Lightcap

No Comments