01 Oct Snakebitten in the Sierra

Mountain outing turns potentially deadly after a surprise attack

It happened when I least expected it. But then again, I never expected it to happen at all.

On the eve of a Yosemite backpacking adventure, in the care of an exceptionally experienced team, a friend and I decided to take a walk around the beautiful 40-acre ranch where we were staying in Midpines, California.

It was dark out. We had just arrived at the car to grab a headlamp for our stroll. That’s when I felt it: the hot needle-prick sting of a wasp on my flip-flopped foot.

Smarting and confused, I looked down for a sign of the stinger. Instead, I found the vampiric bite marks, perfectly formed and just starting to well over with blood.

I looked back to where I had walked. Sure enough, there was the serpent, still defensively coiled in the shadows of a woodpile.

“Oh no,” I thought.

The young rattlesnake that caused the author a world of hurt with a single unsuspecting bite, photo by Matthew Renda

The young rattlesnake that caused the author a world of hurt with a single unsuspecting bite, photo by Matthew Renda

Poisoned Veins

If you’re ever bitten by a venomous snake, remain calm. Keep your breathing measured and your heart rate as slow as possible.

Sucking at the wound may feel helpful, but it’s an empty gesture, best not even bothered with, experts say. And making a tourniquet will only make things worse, with all the swelling that’s due to follow.

Elevating the injury to ease the pain may also be an instinctual reaction, but that, too, is ill advised. It only sends the tainted blood closer to your heart.

Once the poison is in your veins, the goal is to prevent it from picking up too much speed—that, and actively making your way toward help, which should be done carefully but with intentional haste.

I didn’t know any of this at the time, but I was at least able to intuit the concept of deep breaths. Incidentally, the tactic also helps bring clear thoughts.

Steadied anew with each exhale, my mind snapped into action. “Take a picture of the snake,” it ordered. “Call the hospital. Determine exactly what bit you and what needs to be done.”

The photo was blurry but the markings were clear: It was a rattlesnake—a young one by the looks of it.

As I later found out, this was a cause for concern. Adolescent rattlers pack a vicious bite, often releasing all the venom they’ve got in a given attack, still not quite able to control the defense mechanism.

At the time, I thought: “At least it was a small one. It could’ve been worse.”

That’s when my face went numb.

Rattlers are easily identifiable by their eponymous noise-making tails, photo by Sylas Wright

Rattlers are easily identifiable by their eponymous noise-making tails, photo by Sylas Wright

Potent Punch

The venom delivered by Crotalus oreganus, better known as the Northern Pacific rattlesnake, is a hemotoxin. It works by ravaging the cardiovascular system, demolishing blood cells and tissue without regard, and preventing the body from forming defensive clots.

A brilliant bit of natural weaponry, the poison becomes doubly potent once it reaches muscle fibers, which turn toxic themselves when broken down in the bloodstream and, if left unchecked, will go on to destroy the kidneys.

In the wild, that efficiency is aided by the panic that sets in when an animal realizes it’s been tagged. Heart rate already spiked with fear, the bitten creature’s problem is only exacerbated by the natural instinct to run, which gives the poison a circulatory boost. It’s shock, rather than death, that typically stops the intended prey in its tracks.

I could relate. The undulating sensation of tingling numbness—a courtesy of my nerve endings reacting to the foreign substance in my system—had spread from my lips down to my legs. This was not normal.

The thought hit me fully formed and all at once: I could die. And the Mack Truck weight of it all knocked me out.

I came to a moment later, being hurriedly carried to the waiting car outside, my companions doing all the running and panicking for me.

Emergency Care

On the 20-minute ride to the hospital in Mariposa, it became harder to keep my breathing in check. The weight of the situation was sinking in. It was a bona fide emergency, and every mile traveled in the direction of help only made it realer.

Those thoughts were not allayed by the rushed entrance into what felt like a frenzy.

Head bobbing now and vision blurred, I was stripped down and poked at in no discernible order. A hasty attempt to get an IV into my left arm resulted in a busted vein. A second go at my wrist proved more successful, along with a matching line for my right elbow. Tubes and wires were twisted up, yanked and inserted. A breathing tube was administered as a precaution, later joined by a tangle of EKG leads and a pulse monitor.

Then came the Sharpie, tracking the telltale signs of the venom up my wildly ballooning leg. Through my foot to my ankle and slowly into my calf, each new development was dutifully marked on my tender, bruised skin like so many notches in a homemade growth chart.

I was tracing this upward journey when the doctor arrived. I could get the antivenin treatment, he said, as soon as I signed this form.

“What does it say?” I asked.

“It says you acknowledge the risks of receiving antivenin,” he replied.

“What are the risks?” I said, a new small panic blooming.

“Well, since it’s made using a bit of actual venom, some people have an allergic reaction, which, if it’s bad enough, could cause you to go into anaphylactic shock, or die,” he said. “But I’ve been on the job 26 years, and I’ve never seen it.”

“Well,” I thought, “If I’m going to die, I may as well do it by trying to live.”

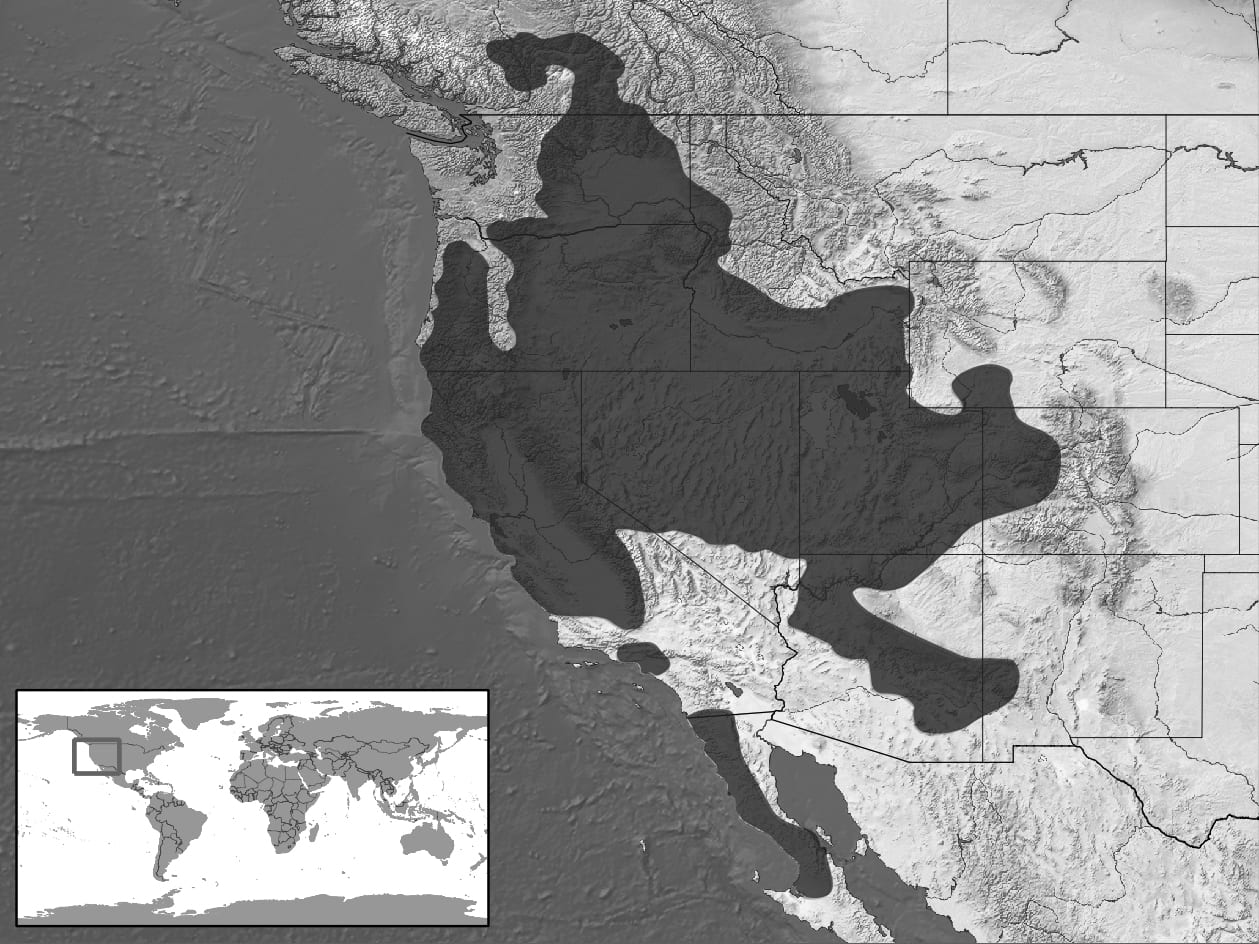

Geographic distribution of the Northern Pacific rattlesnake

Geographic distribution of the Northern Pacific rattlesnake

Survival of the Bitten

In fact, it’s quite rare to die from a rattlesnake bite in the United States. The Centers for Disease Control records an average of just five deaths a year from venomous snake bites, despite more than 7,000 annually reported incidents.

Left untreated, a bite will lead to major organ failure and, eventually, death. But the whole process can take up to 12 hours, leaving a large window of opportunity for victims to seek proper treatment.

That doesn’t mean the quest for help should be leisurely. Depending on the placement and severity of the bite, as well as the victim’s health condition and size, the danger of death could be much more immediate. Receiving antivenin within the first two hours is crucial to ensure a full recovery. Tissue damage can be massive and permanent, or bad enough to require amputation.

And in the meantime, the experience is excruciatingly painful, with skin stretched paper-thin over increasingly engorged extremities.

I made it to the hospital and was treated in just over an hour. By the nurse’s estimation, I had avoided losing my foot by about an hour or two.

Not that the process of keeping it was easy.

Antivenin is akin to an antibiotic, flooding the body with pre-harvested antibodies to help fight off the poison. The medicine must match the specific type of toxin—in my case, that belonging to a pit viper—in order to be effective. Many hospitals in the United States are stocked with antidotes for at least their area’s most common type of venom. For this, I am eternally grateful.

The recommended full course of treatment involves four infusions of the serum, administered at intervals of six hours. In between doses, which feel like a cool, blissful stream of relief, a patient’s blood levels are closely monitored, to ensure the body is accepting the substance. After the initial dose, a patient is observed one-on-one by a hospital staff for at least 15 minutes, to ensure there are no signs of shock—or worse.

At the hospital where I was taken, I was the third snakebite victim of the year, but the first to experience the full effects of the venom. The other two cases had been “dry bites,” involving fangs only, no poison. Mature rattlers, much more judicious with the toxin than their younger peers, commonly employ this strategy as a defense.

My condition made me a particularly rare sight, even in a hospital so close to Yosemite. And by the end of my 22-hour stay, I had a new nickname: Snake Charmer.

The author’s poisoned leg, still swollen in the aftermath of a rattlesnake bite, courtesy Bridget Clerkin

Snaking Upslope

The hospital staff said my case kept them on track to reach their average of six bites a year. Which seemed rather small to me, all things considered.

Yosemite is in the heart of Crotalus oreganus territory. The snakes can be found throughout California, as far east as western Colorado, south to the Baja Peninsula and north to British Colombia.

But even within such a large range, the snakes are gaining new ground—including the Lake Tahoe Basin.

Long considered immune from the serpents thanks to its cold winters and high altitude, the area is experiencing a rise in rattlesnake sightings, and at least one bite victim—a dog—was reported at Loch Leven Lakes on Donner Summit last year, according to Will Richardson, executive director of the Tahoe Institute for Natural Science.

Lover’s Leap near Echo Summit is a particularly snaky haunt, says Richardson, particularly during the spring. The area provides plenty of rocky nooks and crannies for the private reptiles to hide in, and climbers and other nature lovers are advised to watch their step. Richardson says a rattlesnake also turned up at a home in South Lake Tahoe a couple years ago.

The increased presence in recent years is likely due to a shift in climate, with summers in the Tahoe region becoming consistently longer and warmer, Richardson says. Temperature is a huge regulator for snakes’ metabolism, their ability to digest and their energy level in general, with the warmer climate promoting more serpentine activity. And while Tahoe area sees frigid winters and deep snow, the snakes are able to hibernate through the season, Richardson says.

Rattlers are also excellent communicators, using their eponymous noise-making tails to let people know how they’re feeling. This courteous warning system is a big reason for the discrepancy between the snakes’ huge swath of territory and the relatively few incidents of attack.

One exception is, again, younger snakes, as their rattles may not be fully developed, leading them to strike without warning.

Yet even that situation can be avoided by employing vigilance on the trail. As always, the key to safely enjoying Mother Nature is treating her creations with due respect.

Author Bridget Clerkin enjoys the Yosemite Valley after her 22-hour stay in the hospital, courtesy photo

Road to Recovery

The pain from a rattlesnake bite doesn’t stop when the treatment is over. The recovery process is arduous—and slow. It was several days before I could walk very far without crutches, and several weeks before all traces of the swelling had gone.

And all the time, just like the snake that produces it, the poison clearly announces its presence: a constant aching in the veins, making comfort impossible. If I sat with my foot elevated, I would feel it trickling up my inner thigh. Standing up sent it all sloshing with a sharp rush back to my foot. “Tainted blood,” I thought. It felt malicious. I imagined it colored black.

Yet, in time, the discomfort subsides. Mindful breathing was once again helpful, allowing me the time and peace of mind to adapt my pain threshold. Yoga, too, was useful in keeping the stiff joints and sludgy blood moving—but not too much.

Above all, patience was the key to recovery.

Born with a restless spirit, the idea of taking it easy was a difficult one for me, but a beneficial one for my foot.

The repose was also helpful for making future plans. It gave me the time to start arranging my next Yosemite trip. Though this time, I fully expect to finish the hike—and leave my flip-flops at home.

Bridget Clerkin is a writer based in sunny San Diego. She hadn’t anticipated crossing “rattlesnake bite” off her bucket list quite yet, but is pretty happy to be done with that one now.

Rochelle croce

Posted at 21:13h, 02 OctoberVery informative, eye opening and interesting. Never knew these facts. Thanks for the info.

James Balzer

Posted at 15:11h, 31 AugustVery well written! Glad you made it; what a wonderful treatment you received at the hospital!!