04 Oct From Tallac to the Top of the World

South Shore native Craig Calonica has led a life of adventure, from skiing the steeps of Mount Tallac to launching a cutting-edge helicopter skiing operation in the Himalayas

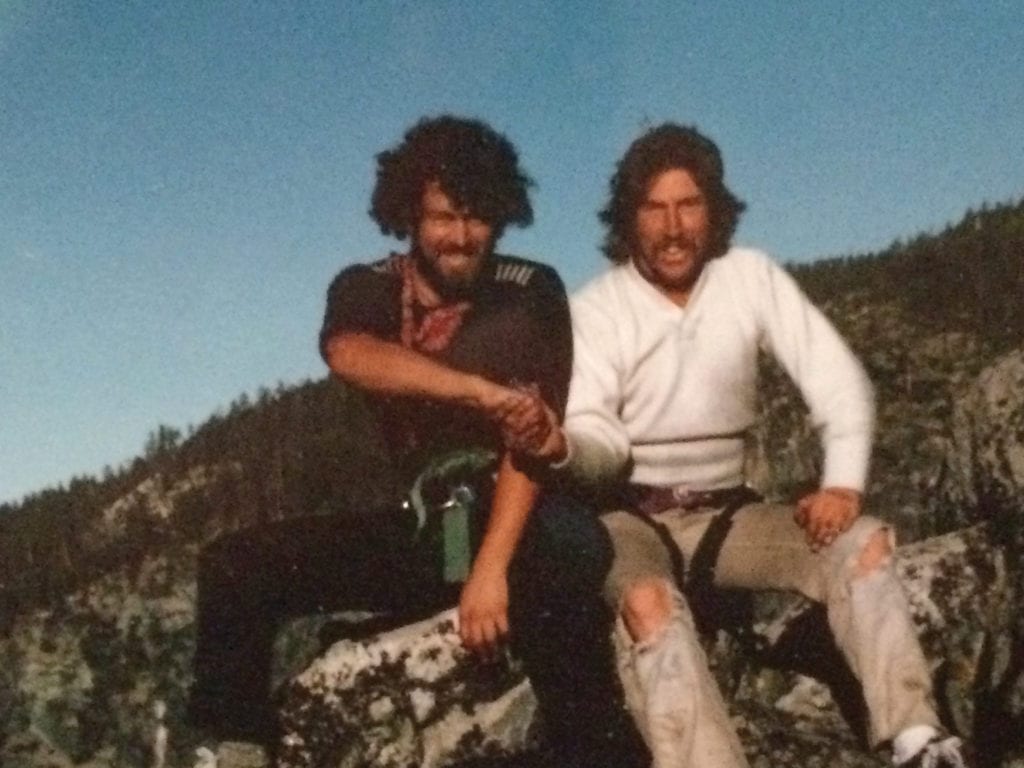

Craig Calonica, left, and Bob Carter celebrate climbing The Shield route on Yosemite’s El Capitan in the mid 1980s, courtesy photo

It’s late June in Chamonix, France.The first golden rays of sunshine are coloring the verdant lower shelf of the Aiguilles Rouges. On the other side of the valley, glaciers flowing from the ice-encrusted summit of 15,780-foot Mont Blanc, the highest peak in Western Europe, remain shadowy. Only the peak’s summit flames golden as another busy day in the summer tourist season has yet to commence.

On the Rue Paccard, Chamonix’s popular pedestrian walkway, locals walk their dogs with climbing ropes as leashes. Blooming geraniums explode from second-floor window boxes. Shop owners sweep entryways, their weathered, wrinkled faces warmed by the rising sun. It’s so quiet that one can hear the creaks of wooden doors swinging open, the clinking of ice screws on climbers’ harnesses, and the swift, rhythmic tapping of joggers’ shoes.

At the southern end of the cobblestone pathway, underneath Chamonix’s famous granite needles, or “aiguilles,” chatter emanates from Jonction Café. The town is known as the birthplace of mountaineering because of what has happened 2 vertical miles above the Rue Paccard, but it’s down below, at coffee shops like Jonction, where many stories are hatched. This day turns out to be no different, yet I have no idea Lake Tahoe will be involved.

I’m here to research a famous French snowboarder’s disappearance on Mount Everest, the world’s highest mountain. In 2002, Marco Siffredi disappeared while attempting to descend the vaunted Hornbein Couloir on the mountain’s north face. Here to shed some light on the subject is Craig Calonica, a 6-foot-3-inch, sturdily built, gray-haired former U.S. Ski Team member and big wall climber who attempted to ski Everest three times.

Not long after Calonica passes through the café’s glass door and just before his second cup of coffee, it becomes apparent he is the stereotypical Chamonix climber-skier-extremist whose resume measures longer than the 220s Calonica once skied in Tahoe. Although he provides a much-needed perspective on Siffredi, Calonica’s own contributions to outdoor adventure piques my interest.

From California to Tibet, Calonica’s fingerprints have smudged various major milestones. So, before long, the conversation turns from Siffredi to Calonica. By the time we leave the coffee shop and walk onto a Rue Paccard that is swollen with tourists, I learn that Calonica’s roots extend to a golden age of skiing and climbing in Lake Tahoe and Yosemite. Most intriguing, however, is learning that his roots sprouted just a few miles from my own home in South Lake Tahoe.

Steve McKinney, Dick Dorworth, Craig Calonica, Otis Kantz, Tim Tilton and Bill McKinley (left to right) on a ski tour around Lake Tahoe in 1978, courtesy photo

Steve McKinney, Dick Dorworth, Craig Calonica, Otis Kantz, Tim Tilton and Bill McKinley (left to right) on a ski tour around Lake Tahoe in 1978, courtesy photo

Running With the Squaw Pack

Calonica, now 63, grew up on 13th and Tata in the Gardner Mountain neighborhood on the South Shore of Lake Tahoe. He was born in the central San Joaquin Valley and moved to Tahoe when he was 4. He became an accomplished member of the Heavenly Blue Angels ski team, mastering several disciplines and becoming one of the top alpine ski racers in the country. After graduating from South Tahoe High School in 1971, he headed north along Highway 89 to Squaw Valley, where he rented a home with other vagabonds.

In the summer of 1971, Calonica met Bob Carter. He recalls hiking to Shirley Lake and creating a makeshift rope swing from a tree. Carter and Calonica spent hours jumping into the lake’s waters, a benign, carefree moment that came to symbolize the youth and freedom Calonica and others fondly remember from those days. (The resort eventually removed the tree and ended the Shirley Lake rope swing era.) It was also at Squaw, in the decade after the 1960 Winter Olympics, that Calonica met a renegade band of skiers and climbers who spawned a movement, some of them becoming North America’s most accomplished alpinists.

“In the early 1970s, Squaw Valley was becoming an old resort,” says Don Lounibos, a Petaluma resident who migrated to Squaw after graduating from University of San Francisco. “It was fairly run down since the Olympics. Housing was deteriorating, lifts were deteriorating, and it was an affordable place to ski. It was probably anywhere from $40 to $100 per month for rent, a pass would be $125, a locker at the mountain would be $25, so the cost of living was very affordable. Most of the people living in Squaw were very good skiers, most of them were college educated and the quality of life was very good. It was a great time to be there.”

Two of the more influential figures in the valley at the time were Jim Bridwell and Kim Schmitz, two ski patrollers and climbers who took Calonica and others under their wings and formed a bond buttressed by adventurous pursuits. Through climbing and skiing, a lifelong friendship formed between Calonica and the Squaw Valley icons.

Calonica (sitting on right) relaxes after completing his first El Capitan climb via The Nose route, circa 1978, courtesy photo

Calonica (sitting on right) relaxes after completing his first El Capitan climb via The Nose route, circa 1978, courtesy photo

Having been an accomplished youth ski racer with the Blue Angels, Calonica was a competent skier when he arrived at Squaw. He excelled in several disciplines in Far West events, but it was his penchant for speed that set him apart from other Squaw skiers. And if it weren’t for two future world speed skiing champions, Steve McKinney and Paul Buschmann, Calonica would have been the fastest skier at Squaw.

McKinney, who died in 1990, was the first person to break the 200-kilometer-per-hour speed mark on skis in 1978 in Portillo, Chile. Nine years later, he became the first person to fly a hang glider off Everest (Calonica was on the expedition with several other Squaw locals). McKinney was crowned the world’s fastest skier seven different times from 1974 to 1987, while Buschmann held the title in 1983. McKinney, Buschmann and Calonica buzzed the resort’s steepest faces and brought a style that was foreign even at Squaw. Calonica, to his credit, was only fractions of a second behind McKinney and Buschmann most of the time. So being the third fastest skier at Squaw in those days essentially meant being the third fastest skier in the world.

“Speed is what started skiing being famous in Squaw, with Steve McKinney and Craig and those speed boys,” says Carter, who moved to Squaw from Los Angeles to work on the ski patrol and was also part of the 1986 Everest Hang Glider Expedition. “Craig was a racer and so he definitely had a unique style. I hung out with those guys… Steve taught me the fast kind of skiing, I taught Steve how to hang glide, and that’s just how it worked. We all taught each other things. Bridwell and Schmitz, they taught Craig how to climb, so those two introduced me to these great human beings like Craig and we’ve been friends ever since.”

Not long after Calonica arrived at Squaw in 1971, Schmitz and Bridwell took Calonica climbing on Donner Summit’s Black Wall. Calonica took to the sport and enjoyed the camaraderie he felt with those two. Bridwell and Schmitz exposed him to a new vertical world guided with his hands and mind that took him up slopes, not the one guided by skis and speed that took him down slopes.

“In Squaw, both [Bridwell] and Schmitz wanted to ski with us because they were way into skiing and started following us around,” Calonica says. “Whether it was freeskiing or running gates, every turn and every minute, those guys were with us. We became really close and in return they took us out climbing. They became big brothers to McKinney and me. I actually was quite natural at climbing and comfortable and, right from the start, I knew that I loved it and never turned back.”

Lounibos, who left Squaw in the 1980s to care for his mother, remembers Calonica in this way:

“Craig become a pretty good climber; he excelled and had a good style. Craig was more like a Yoda and a little monkey. He had some grace and style. He wasn’t struggling, he was graceful, and I could see it.”

Calonica on The Wall of the Early Morning Light route on El Capitan in 1990, photo by Kim Schmitz

Before long, Calonica ventured south with Bridwell to Yosemite National Park, which was still relatively untouched territory in the 1970s for big wall exploration. Bridwell was part of the infamous Yosemite climbing group called the “Stonemasters,” who were credited with advancing the sport of climbing in a brash way. Bridwell, who died this year at age 73, climbed Yosemite’s El Capitan “The Nose” route in a single day with two partners in 1975. He also established more than 100 routes throughout North America, but it was perhaps his partying and drug-fueled climbs that made him the most notorious climber in Yosemite at the time.

Nevertheless, he made an impression on Calonica. By 1974, Calonica, with a full head of brown hair and a cherubic face, climbed El Cap under the guidance of Bridwell (Calonica eventually logged more than 22 ascents of the famed granite monolith). Schmitz, meanwhile, had already progressed to world-class status and didn’t climb as much with Calonica once the snow melted at Squaw. Schmitz had climbed many of Yosemite’s great routes in the 1960s, but by the 1970s he had ventured to distant locations to further his career.

Schmitz, who died in a car accident in 2016 at age 70, had a litany of notable climbing first ascents, but perhaps his finest achievement was being the first to climb the Great Trango Tower in Pakistan’s Karakoram in 1977. His most notable achievement with Calonica, perhaps, came in the winter of 1971–72; it was also a historic moment in Lake Tahoe’s backcountry ski history.

The old Hole in the Wall Gang at Fermions Copa del Ora in Truckee. Starting with Sherman Seiders (with hat) and working left are Kim Schmitz, Jim Bridwell, Craig Calonica, Don Lounibos, Dick Dorworth, Galen Rowell, Paul Buschmann, Terry Fitzgerald, Steve McKinney and Carl Gustafasson, courtesy photo

The old Hole in the Wall Gang at Fermions Copa del Ora in Truckee. Starting with Sherman Seiders (with hat) and working left are Kim Schmitz, Jim Bridwell, Craig Calonica, Don Lounibos, Dick Dorworth, Galen Rowell, Paul Buschmann, Terry Fitzgerald, Steve McKinney and Carl Gustafasson, courtesy photo

Conquering the Cross

Mount Tallac, which rises nearly 4,000 feet above Tahoe’s southwest shore, is one of the more popular backcountry destinations in the Basin. At 9,735 feet above sea level, Tallac has several descent routes, but its most famous is the “Cross.” Named for the east-facing snow pattern that becomes prominent during the spring snow melt, the feature is widely known in the Basin; a South Lake Tahoe drinking establishment, Cold Water Brewery, even sells a popular Tahoe Cross IPA.

In the winter of 1971–72, though, Calonica claims the Cross had never been skied. Schmitz, Calonica and other Squaw skiers targeted the route. For Calonica, it was an important feat because he was from South Lake Tahoe and it’s a South Shore mountain. He grew up underneath it and it was a beacon for him.

To stay fit as an elite ski racer, Calonica’s training involved running from his house in Gardner Mountain to Fallen Leaf Lake, up Tallac, and then back via Camp Richardson. To Calonica, Tallac was his childhood backyard, but he had never heard of anybody skiing the route. One afternoon, he and Schmitz began the discussion and Buschmann and others joined them. Within weeks, Schmitz entered the Cross from the north face, Buschmann did the direct line, and Calonica and another skier approached via the main entrance; eventually, all of them skied all parts of the Cross and felt as if they had unlocked a secret.

“You can’t really even turn in there, and with our long skis, our tips and tails were hitting rocks,” Calonica recalls. “We just hopped around in there, just no room to do anything, and it was stupid we even did it. But Kim (Schmitz) talked about it and we knew it was skiable. I had always skied the bowl, but the Cross was something different. We were going back week after week to ski that thing. You look up and it just looks perfect. It’s the line on this great mountain. We loved it.”

Calonica competes in the 1983 Silverton World Speed Skiing Championships, courtesy photo

Calonica competes in the 1983 Silverton World Speed Skiing Championships, courtesy photo

European Pull

By the end of the 1970s, Calonica’s Squaw crew started to go different ways in life but remained connected by climbing and skiing. Sometimes the two sports intertwined, sometimes they didn’t, and sometimes, like for McKinney, it extended into hang gliding. For Calonica, he couldn’t have known it at the time, but a 1974 trip to Europe planted the seed that steered his life’s direction from South Lake Tahoe kid to owner of an exotic and cutting-edge helicopter skiing operation.

In 1974, he and McKinney stepped off the plane in Geneva, Switzerland, as 20-somethings with skis, a duffel bag and big dreams. While Bridwell and Schmitz became more focused on climbing, Calonica and McKinney took their pursuits to the European Alps, which has a long, storied speed skiing heritage dating back to the 1930s. In the mid-1970s, the speed skiing capital was Cervinia, Italy. Located in the country’s Aosta Valley at the foot Mount Cervino (known as the Matterhorn by everyone else), Cervinia is where the fastest skiers in the world congregated, and that’s what Calonica was.

Quinto Lazzarotto, Steve McKinney, Mr. Zamburlini, Tom Simons and Craig Calonica (standing left to right) with Zamburlini’s children in 1978, courtesy photo

Quinto Lazzarotto, Steve McKinney, Mr. Zamburlini, Tom Simons and Craig Calonica (standing left to right) with Zamburlini’s children in 1978, courtesy photo

Although speed skiing didn’t have a professionalized touch (they were supposed to be amateurs), Calonica and McKinney still found a way to carve out a living from it. In all, Calonica spent 15 years on the international circuit.

“We came back from that trip and said, ‘Speed skiing is what we have to do,’” Calonica says. “I was a slalom skier and good on the technical downhills, but Steve was a good downhiller, so we said, ‘Sure, why not?’ Next thing I know we have a long career in speed skiing. We were coming over, racing Europa Cups and speed skiing. At that time amateurs weren’t supposed to accept money, but we did. They were paying us and they helped us and we were allowed to focus more on skiing, which is now what happens all the time.”

When he raced internationally, Calonica used Chamonix as his home base and made friends there. The more time he spent in Chamonix, the more his focus shifted from racing and speed skiing to combining his passions.

Craig Calonica and Jan Reynolds during their Everest Grand Circle the winter of 1981–82. As Calonica explains: “We were trying to dry out our shoes, socks, gloves, etc. We were lost, had no food for the past five days and a big storm was taking place. Ten days before this, we had just made a winter ascent on Pumori via a new route… We had no food left and so we began walking out in a full-on blizzard with no idea where we were because our sherpas (who couldn’t get in due to the storm) also had the map for that area with them,” courtesy photo

Craig Calonica and Jan Reynolds during their Everest Grand Circle the winter of 1981–82. As Calonica explains: “We were trying to dry out our shoes, socks, gloves, etc. We were lost, had no food for the past five days and a big storm was taking place. Ten days before this, we had just made a winter ascent on Pumori via a new route… We had no food left and so we began walking out in a full-on blizzard with no idea where we were because our sherpas (who couldn’t get in due to the storm) also had the map for that area with them,” courtesy photo

Chamonix

Fifty miles from Geneva, Switzerland, Chamonix first attracted tourists in 1741 when Englishmen Richard Pococke and William Windham found what they called the “Chamouny” valley. Their visit to the remote valley was considered the first by outsiders for purely recreational purposes. They encountered a population of farmers whose lone industry was the harvesting of oats and rye. By 1821, the world’s first guiding service, the Compagnie des Guides de Chamonix Mont-Blanc, was formed in Chamonix. Guiding became the profession that would help define Calonica’s life.

Guides led all types of tourists—from future climbers to Victorian women wearing dresses and high heels—over crevasses and introduced them to an alpine world, but mostly to climb Mount Blanc. There was simply no shortage of people drawn to this scenic narrow canyon split by the rushing waters of the 62-mile L’Arve River. With waterfalls, glaciers and peaks rising as high as 12,000 feet on both sides, there was no need to search for Shangri-La in the Himalayas. People found it right there in the Alps.

With such an attraction to dangerous mountains came calamities. Since crystal collector Jacques Balmat and physician Michel-Gabriel first climbed Mount Blanc in 1786, there have been an estimated 8,000 fatalities on the massif, which includes the ice-covered summit and its assortment of satellite needles. These days, about 100 people die each year on the massif, and in the summer climbing season, there can be 20 mountain rescues a day.

“I hate coming (to Chamonix),” journalist Laurent Molitor once said. “It smells of death. In Chamonix, death is sport.”

Deaths didn’t deter people from climbing and skiing in Chamonix. In fact, quite the opposite happened. Between 1924 and 1956, four cable cars were constructed to whisk anybody with a pulse thousands of feet above the valley floor in a matter of minutes. This created unfettered access to the most expansive ski terrain in the world, and provided a significant head start for climbers hoping to scale Europe’s most serious peaks. Before long, the two activities blended together in Chamonix. Calonica was heavily involved in this movement.

“Once I came to this place, we were just going for it,” says Calonica, who moved to Chamonix permanently in the late 1990s and fathered his daughter there (she is now 19). “We were doing stuff that people who grew up here didn’t even think of doing because, well, they knew more than us. We didn’t know any better. They were like, ‘Hey, you can’t do that here. There are all these crevasses and you’re going to get yourselves killed.’ We’re like, ‘What are crevasses?’

“But now, spending the last 20 years here, I know the certain places and the certain things you just don’t go do. That is the mistake a lot of people make when they come here. You can’t just go ski whatever you want—going through a minefield and all sorts of hazards… But that was one of the attractions to me about Chamonix. It was very free and wild.”

Calonica stands under Machhapuchhre, aka Fishtail Peak, in the Annapurna Himalayas, courtesy photo

Bigger Mountains

Calonica’s maturation as a skier and climber in such a serious environment was evident, and it allowed him to take his talents to the most extreme mountain range in the world: the Himalayas.

About a decade before he permanently moved to Chamonix, in 1986, he joined several of his former Squaw friends—including Carter (now a Truckee resident) from his Shirley Lake rope swing days, and McKinney—on the 1986 Everest Hang Glider Expedition. The expedition almost didn’t get started because the hang gliders were impounded by Chinese customs officials, who had an unpleasant interaction with Calonica.

“Craig went ballistic,” Larry Tudor told Cross Country Magazine in a 2013 article. “His eyes turned blood red like a deer in your headlights. He grabbed the customs guy, yanked him over the counter and with his face inches away told the interpreter, ‘You tell this guy these are our gliders, we paid for them, we are here with permission from his government and if he doesn’t give them to us right now, I’m going to twist his head from his skinny little neck.’”

The gliders were released.

Calonica’s outburst helped McKinney record one of the first recorded flights from Everest (on the west ridge). Calonica and Carter supported the expedition by hauling the gliders and other required gear between camps. One day, while hauling loads between Camp 1 at 20,000 feet and Camp 2 at 22,000 feet, they had their skis with them and descended to Camp 1, making figure eights in untouched Himalayan powder.

“We were out of breath and it wasn’t a long descent, but you could tell there was potential,” Carter says.

McKinney wasn’t the only one from the Squaw group to leave his mark in the Himalayas. Between 1986 and 2001, Calonica made several first descents in the Himalayas and made three unsuccessful attempts from the summit of Mount Everest in 1997, 1998 and 1999. At 29,035 feet, Mount Everest’s fickle weather patterns don’t always produce prime skiing conditions, especially in the post-monsoon when coverage is usually best.

“And of course about the time I took a year off, someone pulled it off,” says Calonica, referring to Slovenian Davo Karnicar, who became the first person to ski from the summit of Everest in October 2000. “It was worth being the first person to ski from the summit of Everest and that is why I accepted the risk. Eight thousand–meter Himalayan skiing is kind of like big wall climbing—it’s an awful lot of work. It’s a really hard endeavor and the chances of pulling it off are pretty slim, and the chances of dying are pretty high.

“It was on my last attempt to ski Everest that I thought about heli-skiing there. Then I was on my third attempt and I had just spent two months at high altitude to make one run and I started thinking: ‘If I had a helicopter, I could ski that peak after lunch and that peak before breakfast.’ So I went back to Kathmandu and started talking to people.”

Machhapuchhre, aka Fishtail Peak, in the Annapurna Himalayas, is revered by the local population as particularly sacred to the god Shiva, and hence is off limits to climbing, courtesy photo

Machhapuchhre, aka Fishtail Peak, in the Annapurna Himalayas, is revered by the local population as particularly sacred to the god Shiva, and hence is off limits to climbing, courtesy photo

Heli Business

Also by the late 1990s, Calonica was in his 40s and his interests were shifting again. No longer was it about attempting the most daring descents or climbs, but he still wanted to play in mountains. Many of his friends were guides in Chamonix, and now with significant experience in the Alps and Himalayas, he felt he could provide a unique type of experience. He soon hired many of the top climbing and backcountry skiing guides for his guiding business, and by the turn of the century had established Nepal-based Himalayan Heli Ski Guides.

Calonica operates the business out of Pokhara, about 100 miles from Nepal’s capital of Kathmandu. He began leading clients on first descents in the Annapurna region of the Himalayas in 2003, with his guides providing ski lines measuring nearly 2 miles long. And the best part—nobody else in the world is doing it, and Calonica feels as if he’s made a unique contribution to the skiing world.

“I was climbing and skiing big peaks when I started, but it was a new kind of competition in Chamonix when I moved there in the late ’90s. You had to be doing something that was pretty incredible to get a sponsorship, and when you had these guys doing the stuff they were doing in Chamonix, they were upping the level to an insane type of level, to the point where I said, ‘No, I am not going to play that game,’” Calonica says. “These guys were basically in a race to see how many things they can do before they die. That’s why it should be called Death Valley instead of Chamonix.”

Heli-skiing in the Annapurna Sanctuary in the Himalayas, courtesy photo

Calonica now prides himself on safety. With more than three decades taking people up big walls in Yosemite or on big ski descents in the Himalayas, nobody around him has been injured, let alone died. At 63, he’s not interested in breaking that streak. These days, Calonica—who is still based in Chamonix when not traveling—guides in Nepal, Greece and South America’s Tierra del Fuego; this winter, his company will become the first to offer heli-skiing trips to Antarctica.

Calonica has plenty of famous moments in his life. Privately, perhaps no moment would’ve made him more famous than if he could have substantiated his claim that he saw a Yeti in the Himalayas.

“I asked him, ‘What kind of drugs are you on?’” jokes Lounibos, whom Calonica had called on that trip for a weather report. “Once I told him the weather, I asked if I could try some of them.”

Publicly, though, his most famous line came in the 2011 Red Bull Media film The Art of Flight. In one part of the film, when professional snowboarder Travis Rice and friends are charting their options in Patagonia, Rice casually points to various parts of the map to state his plan of execution. Calonica doesn’t appreciate Rice’s cavalier regard for the terrain and barks: “What planet the [expletive] are you from?”

“If you are guiding someone, they hired you to make good decisions and calls,” Calonica says. “If it’s not happening, you just walk away. We will go back another day.”

Brothers Craig (left) and Gerry Calonica at Heavenly in May 2018, courtesy photo

Calonica still sometimes relies on weather forecasts from Lounibos in Petaluma, but Lounibos wonders when there won’t be another day. When he’s in the United States, Calonica stays with him or Carter in Truckee, or others who are still alive from those Squaw days in the 1970s. Yet, Lounibos ruminates if time is still on their side, and wonders how much longer Calonica can flirt with danger.

“The old-crowd people from Yosemite and Squaw and Bishop are slowly going,” says Lounibos, who’s now in his 70s and was with Bridwell days before he passed earlier this year. “I worry about Craig. I’ve talked to him when he’s had problems with clients. All it takes is once [for a client to compromise his safety], and I love his stories when we see each other, but I worry about the day when he doesn’t come back.”

Jeremy Evans is the South Lake Tahoe–based author of In Search of Powder and The Battle for Paradise. His forthcoming book, Marco, tells the story of Chamonix snowboarder Marco Siffredi and his peculiar disappearance on the north face of Mount Everest in 2002. Learn more about Evans at www.jeremyevans.org.

paul

Posted at 19:35h, 16 NovemberTalbs, I assume this is you getting all this great story telling out onto the web Thanks, Do you remember who was in the gang from the mars Hotel that skied The Cross I think it was the Spring of 1976. Peace

Linda Lindsay Stallcup

Posted at 10:49h, 02 JulyWinter 1977/78 Olympic Valley, California

Rhonda Rose introduced me to Craig one night and he took us to Brockway Hot Springs on the Lake. We had all graduated from South Tahoe High School, had lived on Gardner Mt.. and we loved to ski (still do).

John Talbott

Posted at 05:54h, 10 MayI took the photo of the group seated at Fermins’ about 1976, someone’s BD, maybe Carl’s. (note his torn shirt from wrestling in the street beforehand w/ McKinney). i was sitting b/w Steve and Terry and had my 110 pocket camera so stood on a chair for the classic snapshot