27 Sep The Shape of Snowboarding

From pow surfers to twin tips and back again, the history of snowboarding can be seen in the evolution of board designs, some of which have made a comeback after decades of dormancy

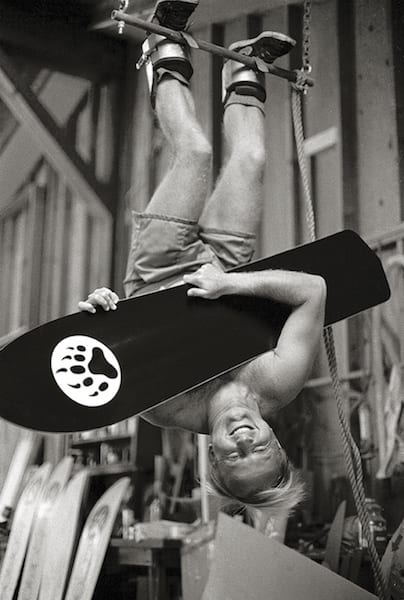

Chuck Barfoot, 1984, photo by Bud Fawcett, budfawcett.com

In 1978, a designer named Chuck Barfoot built himself a snowboard. He had already been working with his friend Tom Sims on some different shapes, and the latest rendition—made of fiberglass and foam—needed some field testing.

So Barfoot and fellow designer Bob Weber road-tripped from their headquarters in Southern California to the cold champagne powder of Little Cottonwood Canyon, Utah, and had themselves an epiphany or two.

“On Christmas day, 1978, I took a run in 18 inches of powder, made surf turns to the bottom, and hooted, ‘This is it!’” says Barfoot. He held the board above his head and hollered in elation.

Barfoot—who would go on to be a pioneer in the snowboard industry—had never ridden a snowboard until that day, despite being a designer, surfer and skater for years. Those first turns for Barfoot on snow represent a microcosm of the nascent industry, where a mix of educated guesses coupled with a deep love of gliding over powder pushed things forward.

Going back to the 1980s, ’70s and even ’60s, designers like Barfoot were trying to reproduce the joy found from surfing in the ocean, while also drawing from skateboarding and skiing to eventually create something called snowboarding.

It was a patchy start. Boards were fragile, expensive or both. The sport was laughed at by the established ski industry, banned for years by virtually all ski resorts, and many early companies failed after a few years.

Despite this, or perhaps because of it, the sport never quit, becoming a billion-dollar global industry by the new millennium, with board design ebbing and flowing with the times.

“We had no idea what was to come,” says Bob Klein, who was part of Tahoe’s initial snowboard movement in the late 1970s.

An original Snurfer owned by Norm Sayler, photo by Sylas Wright

The Early Days

Snowboarding, despite what many think, is pretty old. Villagers in the mountains of Turkey are believed to have ridden a flat, toboggan-like device down snow as far back as the sixteenth century. Austrian miners reportedly did something similar, and many other anecdotes exist, albeit not fully validated, including claims of U.S. soldiers riding sideways on barrel staves during World War I.

The history gets less fuzzy in 1965 with the invention of the Snurfer by Sherman Poppen (who passed away in July 2019) in Michigan. The Snurfer has the rough dimensions of two kids’ skis bolted together side by side—because that’s exactly how Poppen got the idea—and had a rope going from the nose to the rider’s hand for stability.

More than a million Snurfers were sold, and it’s widely credited as the precursor to modern snowboarding, spurring some key players to think about its potential.

“The Snurfer spawned all this creativity within a demographic that had gotten ahold of these boards and said, ‘Wow, there’s more to this here.’ Nobody knew what was there, but there was something there,” says Jeff Grell, a snowboard designer who worked for Sims and other companies—and is credited with inventing the highback binding, one of the sport’s biggest design breakthroughs.

However, some rejected the Snurfer outright, and were dedicated to making the sport a hands-free experience. Tom Sims—founder of Sims Snowboards, perhaps the most influential early company in snowboard history—told the Skiing History Association, “When you have a rope on the front of a board, it is no longer snowboarding. When you are dragging a stick for balance behind you, it is no longer snowboarding… Snowboarding is riding a single board down a mountain with your hands free.”

Founded in 1976, Winterstick’s progressive designs included swallowtail models that allowed riders to stay on top of the snow, photo by Dave Zook

‘Stickin’ the Steeps

Before Burton and Sims kicked off a battle for industry dominance, a progressive-thinking, Holland-born East Coaster named Dimitrije Milovich was surfing the steep slopes of Utah.

Milovich moved to Utah in the winter of 1972 with friend Wayne Stoveken with snowboard plans in his head, determined to break down some doors for surfing on snow.

A few years later he founded Winterstick. The progressive snowboards he made—with a pointy nose, wide around the front foot, and a sharp taper going to either a narrow roundtail or his signature deep swallowtail—allowed the rider to stay on top of the snow and make long carving arcs, a different world entirely from the low-angle wiggle turns of the Snurfer.

“Winterstick technology was so far ahead of everyone else. I haven’t seen anyone replicate that technology since,” says Grell. “He somehow managed to integrate a P-tex base, a foam core and a fiberglass top sheet into one, when everyone else was basically just gluing pieces of wood together. What he created were just these three-dimensional pieces of art.”

Milovich received two patents for “Snow Surfboards” in 1974. Note the patents weren’t for snowboards, as an official name was not yet determined. Terms such as snurfer, skiboard, mono-ski, snoboard, skifer, snow surfer, winterstick (early riders called snowboarding “stickin’”) and more all vied for the official noun—bringing to mind a line from author Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s famous introduction to One Hundred Years of Solitude: “The world was so recent that many things lacked names, and in order to indicate them it was necessary to point.”

While his designs worked, Winterstick struggled to attract industry interest, and they sold fewer than 1,000 boards in a six-year run. Milovich moved away from Winterstick in 1982 (the brand remains in business, but under different ownership) and he now runs an engineering company.

“It’s as bad to be too early on a trend as it is too late,” Milovich told Deseret News in 2003.

Damian Sanders tests the capabilities of an Avalanche snowboard at Slide Mountain, circa 1985, photo by Bud Fawcett, budfawcett.com

Industry Infancy

Surfing provided the main inspiration for early designers, with the main snowboard brands being founded around the country in the late 1970s and early ’80s, setting the stage for the modern industry.

“I noticed that the innovators of snowboarding just imitated what they liked doing on the water in the summer, and translated it to the winter,” says Earl Zeller, co-founded of Avalanche Snowboards. “As it has been said a million times over, snow is just frozen water.”

Winterstick and Sims were founded in 1976 in Salt Lake City and Santa Barbara, respectively. Barfoot then parted ways with Sims and started his own brand, Barfoot Snoboards, in 1981. In South Lake Tahoe, Zeller, along with Chris and Bev Sanders, started Avalanche Snowboards in 1982. GNU Snowboards out of Washington debuted in the early ’80s, as well as a number of other brands such as Kemper, Flite and many more. And not least, a former New York City broker named Jake Burton Carpenter founded Burton in 1977 in Vermont (Burton passed away in November 2019).

It was a time for weird and wonderful experimentation.

Stemming from surfing, all boards had fins or skegs for a time. Avalanche, which introduced the first finless boards for the 1984-85 season, says Zeller, used mahogany door skin cores and Formica topsheets. Wintersticks had metal edges before Milovich took them off because they were not needed for powder riding. Some boards had elegant curves, yet others looked like rectangles, with squared-off boxy tails. Bindings were any combo of bungee cords or leather straps, and some decks had aquarium gravel or skate deck grip tape applied to the topsheet so that the boots—simple snow boots like Sorels—wouldn’t slip.

“It was a natural progression, learning what did work and what didn’t work,” says Barfoot. “Every time you got feedback, you went and built something a little different—more flex, more sidecut, less fins, et cetera.”

Shaun Palmer, Donny Robertson, Vito LaConte, Gino Trinidad, Bev Sanders, Chris Sanders, Earl Zeller and Damian Sanders at Slide Mountain, circa 1984-85 season, photo courtesy Earl Zeller

On the riding end, the ambition was ruthless, and helped give input to designers. “We were riding with rubber straps and golf cleats for bindings in 1983 and jumping 30-foot cornices in Tahoe,” Barfoot says.

Snowboarding was also getting picked up by national media, with pieces on the budding sport published in POWDER, Newsweek and Playboy in the 1970s. But despite the press, riders often barely knew what else was happening outside their home mountain, and were thus seeking out other members of the tribe.

“I would go chase down other riders and talk to them if I saw a board on the roof of a car,” says Damian Sanders, brother of Avalanche co-founder Chris Sanders and one of the top professional snowboarders in the 1980s. “When I did contests later, I couldn’t believe there were that many other snowboarders out there. We thought it was just us.”

Slowly, and through the joy it inspired (and surely a need to pay the bills, in some part), the sport gained momentum as a growing network of riders spread into the different geographical hotbeds, including Lake Tahoe.

Tahoe: The West Coast Powerhouse

California had been steadily growing as a mecca for snowboarding into the 1980s, as resorts like Donner Ski Ranch and Boreal opened their doors to “knuckle-draggers,” with riders also hiking the backcountry of Donner Pass and Mount Rose.

A group of friends at North Tahoe High School—including Mark Anolik, Terry Kidwell, Tom Burt, Klein and others—were particularly instrumental.

This group made history by riding a ditch near what was then the Tahoe City dump, which is considered the first snowboard halfpipe in the world. “Nobody but the few of us who were passionate about these dumb toys ever thought pipe riding would last. We knew it would,” says Klein.

Terry Kidwell styles out a grab at the Donner Quarterpipe in 1986, photo by Bud Fawcett, budfawcett.com

While it was a one-hit feature, the Tahoe City halfpipe attracted photographers and sparked an infusion of freestyle skateboard style, which then influenced board design. Kidwell was the early standout and earned the moniker “the father of freestyle” for his air awareness and progressive tricks and grabs. He was given Sims’ first pro model snowboard in 1985.

The North Tahoe crew soon branched out into their preferred riding styles, says Burt, an early rider for Avalanche along with Damian Sanders and Jim and Bonnie Zellers. For Burt, it was steep and technical terrain, as he would later go on to pioneer lines in Alaska and around the world. He preferred longer boards, in the 170-centimeter range, with traditional camber. Having a ski background helped with the mechanics of a good turn, but Burt sought to go beyond the limits of the skinny skis of the 1980s.

“I wanted to do everything I could do on skis on my board; that was my personal push,” says Burt, who found like-minded big-mountain riding partners in the Zellers. “At a certain point we realized snowboards could do more than skis.”

In South Lake Tahoe, standout riders Shaun Palmer and Sanders, who were in the same high school class, were gaining exposure as well, bathing in a rock ‘n’ roll–infused snowboarding lifestyle, with neon, big hair and beer consumption synonymous with their cutting-edge riding. Sanders famously wore hardboots over the softer snowboard boots, maintaining that they were the only way to support his gargantuan airtime.

While the cross-pollination of surfing and skating into snowboarding (and vice versa) would continue for decades to come, skate influence became more prevalent in the 1980s.

“All of us felt that connection to surfing in the beginning. This was a surfboard for the snow,” says Klein. “Then once we started developing the riding, it was a quick transition to skateboard influence. I think by the early ’80s everyone was looking at skateboarding as the root of snowboarding.”

A lineup of vintage Sims snowboards owned by Brooke Long, who estimates he has around 1,000 boards, photo by Dave Zook

World Snowboarding Championships

Contests, media exposure and resort acceptance all increased through the 1980s, creating a larger, more interconnected snowboarding culture. During the 1984-85 season, only 40 resorts allowed snowboarding. By 1990, that number hit 476, according to the United States Ski Industry Association.

Early contests included slalom, moguls, freestyle, halfpipe and more, and were a popular meeting of the minds for snowboarders. An oft-cited event was the “Worlds” at Soda Springs on Donner Summit in 1983, organized by Tom Sims. The event notably included halfpipe for the first time ever as a judged event.

While many accounts of the competition focus on the brooding feud between Jake Burton Carpenter and Tom Sims, others feel this recollection is off-base. The common story goes that Burton and his race-focused East Coast riders threatened to ban the contest because they hadn’t had a chance to practice in a halfpipe, while the West Coast Sims team had been fining tuning their pipe riding for a few years already.

Folks who were there, like Klein—one of the few West Coast riders on the Burton team—say there was an undeniable resentment between the two camps, but, above anything else, it was based on a cutthroat desire to win.

Vintage Burtons owned by Brooke Long, photo by Dave Zook

“The animosity was not based on, ‘You guys are race geeks and those guys are freestylers.’ It was way more about the personalities involved, and gaining a competitive advantage over one another,” says Klein.

Feuding aside, the event (Tom Sims won the overall) also set the wheels in motion for the board style that would ultimately come to dominate the industry: The twin-tip snowboard, where the front and back of the board is identical, similar to a skateboard design.

Matt Donavon, a Boreal employee, was at the event with the sport’s first “double-ended” snowboard, called the Prop Snowboard, says Barfoot. This shape, though primitive at the time, helped to spark the industry-wide twin-tip shape.

“It looked like an airplane propeller,” says Barfoot, as the board was narrow in the waist and comically wide in the nose and tail. “Matt walks up, straps in, comes down, flips the board around switch stance, makes some turns, and then comes back around regular.”

Donavon, knowing that Barfoot was a snowboard producer, introduced himself, and the two talked design. Although Barfoot’s first ride on the board did not go smoothly—he describes its feel as “a skateboard with the trucks on backward”—he saw its potential for freestyle riding. A year later his partner, Ken Achenbach, built the industry’s first conventional twin-tip boards in Canada under the Barfoot name. By 1985 Barfoot was building them in the States, and the course of snowboard design underwent a major shift.

The twin-tips’ dominance in the snowboard world all but pushed surf-influenced directional boards to the back burner, as it proved to be the ultimate utilitarian solution for the burgeoning freestyle popularity.

“That board basically changed the entire industry,” says Barfoot. “Up until that point, everything was uni-directional and was either a race board or a carving board. Nobody was riding backwards.”

Snowboards from Brooke Long’s collection, which range from Burtons to obscure brands of all shapes and sizes, photo by Dave Zook

A Collector’s Market

Fast forward a few decades to present day Reno, and Brooke Long, soft-spoken and trim in his 50s, unpacks dozens of snowboards and sets them up in a conference room. The room seems to transform into a pop-up snowboard museum.

Long has everything from an original Sims Terry Kidwell pro model to stubby fiberglass designs to neon decks from companies long extinct. Most of his boards are from the 1980s, and some go back further, such as a signed 1960s Snurfer from Sherman Poppen.

Long’s first board, and unofficial start to collecting snowboards, was a Burton Backhill purchased via a mail order catalog in 1983. It was not love at first sight. “I didn’t even like that board,” he says. “My feet kept falling out of the bindings. I almost gave it away to my friend.”

He held on to it, wisely, as that board—one of Burton’s first models—could earn Long thousands of dollars in the vintage snowboard market, where a small but fervent community of collectors use outlets like Ebay, Facebook and Craigslist to swap boards, and keep an eye out for counterfeits.

In a twist of irony, the boards that are being sought out and fought over are literally the same boards that designers were trying desperately to drum up interest for 30-something years ago.

The rarest of the rare can fetch around $10,000. A Londonderry BB1, one of Burton’s earliest models, is going for $75,000 in a Utah snowboard shop (ironically, on the surface, it looks like a souped-up Snurfer).

The rarity and significance of certain boards are two main factors that give the boards their value, explains Long, who estimates he has around 1,000 boards. He acquired them via a combination of online outlets, being personally connected to some of the industry players (he went to college with Burt), and going to pawn shops and offering to buy every board they had for $10 or $15 apiece.

Various Barfoot Snoboards owned by Brooke Long, photo by Dave Zook

One of the boards in Long’s collection is a red Winterstick swallowtail made by Dimitrije Milovich in 1981. It is feather-light with a foam core and oozes surf influence in its exaggerated curves, with the deck covered in tiny spikes for grip, and rudimentary foot straps. Due to the fragility of the board, the small initial production run by Winterstick, and the fact that it’s one of the more rare red models, Long believes this board is one of only two or three still around.

Some collectors see boards as an opportunity to flip them, which cuts against the mindset of folks like Long. “I see this as a really unique opportunity to enjoy snowboarding’s history and kind of assemble it, and talk to the people that were there,” he says.

Mitzi Hodges, who runs Donner Ski Shop in Soda Springs, has a collection of around 100 snowboards. The daughter of former Donner Ski Ranch owner Norm Sayler, she found a “right-time, right place” positioning in the sport.

She caught the collecting bug around 1997 and, like Long, fears that some people are collecting for the wrong reason, simply looking to make money. “I want people to understand

that we aren’t going to get any more of these things,” says Hodges.

To Hodges, snowboards are much more than monetizable pieces of wood and P-tex. She has a personal connection to her boards because of the friends and pro riders she rubbed shoulders with in Tahoe and beyond.

“As I developed my friendships with pioneers of the industry, my love and quest for the boards deepened,” says Hodges.

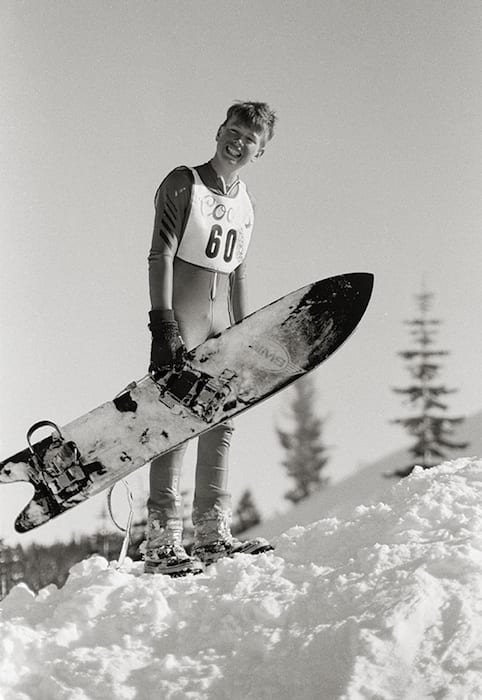

A young Shaun Palmer, aka “Mini Shred,” carries a Sims swallowtail at the 1985 World Snowboarding Championships at Soda Springs, photo by Bud Fawcett, budfawcett.com

The New School is the Old School

For early snowboard enthusiasts who couldn’t find commercial success, perhaps there is some consolation that the directional, surf-influenced board designs of the 1980s are in vogue again, with brands like Jones Snowboards (Truckee-based Jeremy Jones’ company), United Shapes out of North Lake Tahoe, Lib Tech and many more putting modern twists on retro designs.

Burt, who is now a part owner of Winterstick—and a snowboarder who has been riding “pretty much the same boards since ’92”—sees the resurgence of early models as healthy for the sport. “People always want something different. The new boards make certain conditions more fun and they are easier to throw around. Some of them are very similar to boards in the early and mid-’80s.”

For some, the goal today is not to strictly emulate surfing. Gray Thompson, 27, grew up surfing and skateboarding in San Francisco and now runs United Shapes. While he loves to draw influence from the ocean, he believes that surfing and snowboarding are discrete, albeit interconnected, sports.

“There are a lot of design characteristics to pull from surfboards as far as volume and displacement go. However, I believe that snowboarding is a unique enough concept in itself to warrant its own design principles, philosophies and styles,” says Thompson. “When you are freeriding, you are going to come across every terrain imaginable. One run you might be ripping a backside wave that could be compared to surfing, while on the next run you may be dropping in on a 40-degree face in variable snow conditions where edge hold and precision come into play.”

Additionally, some of the stalwarts are still at it, bringing their decades of experience to today’s snow landscape. For example, Barfoot is looking to re-introduce his classic Freakstyle Barfoot model this fall, and sees the shape as relevant as ever.

Professional big-mountain rider Jeremy Jones takes in the view of Lake Tahoe with a swallowtail splitboard reminiscent of the designs of old, photo by Ming Poon

“The materials were heavier back then. Now, we are able to get better flex while using the same shapes. Now you can fine-tune it, lighten the board up, get incredible flex, so that all the curves work together,” says Barfoot, with the same teenage-esque enthusiasm he’s had since surfing in New Jersey back in 1961.

This recycling and evolution of ideas shows that the tinkering of design will go the distance, and helps keep the sport on its toes.

“My philosophy has always been, build something really good that works, take care of people, and they’ll keep coming back,” says Barfoot.

Dave Zook started snowboarding in 1993 and, like the subjects of this article, was a surfer first. He quickly appreciated how much easier a slash is on a snowboard versus a surfboard, and thus stuck with the sport.

Steve Hayes

Posted at 11:59h, 01 OctoberNice work. Pretty much how I remember it…Thx. Steve Hayes

Chuck Barfoot

Posted at 06:05h, 09 OctoberGREAT JOB ON THIS ARTICLE ! 🙂

KEEP ON SHRED-N !

Jeffrey Grell

Posted at 10:05h, 24 OctoberNicely written article.

Jeff Grell

Cliff Daring

Posted at 12:58h, 03 NovemberI still ride my Avalanche Bumps Pro Mogul 165 every few years. I live in North Dakota, but used to work at Big Sky MT. I can’t find *any* information on this board, or even confirmation that it exists! What a shame. But it’s hilarious when I hit the mountain and kids come up to me asking what the heck it is. It’s like the SR-71 of snowboards. I just turned 50, so no more moguls for me…

Rico

Posted at 11:55h, 06 DecemberGreat info and history! Around 1970, a few of us at Tahoe took the bindings off our water skis and put snowski bindings on (in a waterski pattern) and rode powder at Sierra Ski Ranch. The lifties, also our buds, said we couldn’t ride the hill on “those things”, but since they couldn’t think of a reason to ban us, we continued to ride on powder and crud days. We didn’t pursue these rides publicly, but we would probably be into some $$ if we had. Thanx again