14 Dec Trigger Man

Chris Ault invented football’s hottest offense at the end of a Hall of Fame career

Chris Ault doesn’t mind if people credit him solely for his creation of the pistol offense—the hottest new trend in football—and little else. But the Hall of Fame coach can’t help but snicker at the notion.

“It doesn’t bother me, but when they start looking back they go, ‘Hey, you guys weren’t too bad in the ’90s either,’” says Ault, who at 66 remains spry and proud as ever of his University of Nevada football teams, which he coached for nearly three decades over three separate stints. “The pistol is what took off and is affecting the landscape of football from high school to the pro level. But when you go back to my early days when we were throwing the football, we were always a special offensive football team.”

Indeed, Ault carved out a reputation early in his coaching career as an innovative mind, particularly on the offensive side of the football. He thrived on progression, boldly reinventing his Nevada offenses on several occasions to stay one step ahead of his competition.

By the time he ended his college career after the 2012 season, Ault ranked among the all-time college coaching greats, with 233 victories. He was inducted into the College Football Hall of Fame in 2002, three years before unveiling the pistol offense in his third go-around with the Wolf Pack.

“He’s a great competitor,” says Boise State head coach Chris Petersen, who faced off against Ault regularly in the Western Athletic Conference. “There’s a reason he’s in the Hall of Fame. What he did at Nevada, and in different stints, is such a testimonial.”

Yet, it is Ault’s pistol offense that has the football world intrigued, and eager to pick his brain for insight.

Ault’s been a busy man since giving up the reins at Nevada. And he only plans to get busier as he prepares for the next phase of his career—the National Football League.

In May, the Kansas City Chiefs announced they were bringing on Ault to serve as a consultant with the team. He’ll work with former University of Utah and San Francisco 49ers quarterback Alex Smith as he incorporates elements of the pistol into the Chiefs’ offensive attack.

“I’ll tell you what, (working with the NFL has) been a wonderful experience. And I can say that the common denominator is, they (NFL coaches) all think the pistol is here to stay, and it’s a real benefit for a lot of people to use it in a lot of different ways,” says Ault.

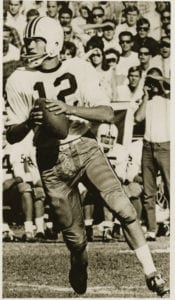

Chris Ault playing in 1967, photo courtesy University of Nevada Athletics

Before the pistol

Ault first came to Nevada as a quarterback in 1965. He was hired as head coach of the Wolf Pack in 1976, after coaching Bishop Manogue and Reno high schools to state championship titles and working as a University of Nevada, Las Vegas, assistant coach from 1973–75.

During his first 17-year run with his alma mater, Ault led the program from a non-conference Division II affiliation into the I-AA’s Big Sky Conference and, by 1992, on to the Division I ranks. In 1980, Ault established college football’s current overtime format. The next year he popularized the middle screen, which is now one of the staples of most offensive systems.

Even in his earliest days, Ault’s Nevada teams always had one thing in common: state-of-the-art offenses.

“Since 1976 when I started, we’ve always been on the cutting edge on offense. Back then, we ran the Wing-T, and there were very, very few teams in the Western United States running it,” Ault says. “That was my first experience of being a team that was going to isolate itself on doing something different and special. I had never run it before I came to Nevada, and we were really good at it. We ran that offense until, really, 1988. And it was special.”

It wasn’t expendable, however, and Ault—who also served as Nevada’s athletic director starting in 1986—scrapped the Wing-T in exchange for a more spread out, pass-oriented scheme in time for the 1990s.

Those were fun teams to watch, says former Reno Gazette-Journal sports columnist Joe Santoro. In 1990, Nevada played into the I-AA national championship, while the following year the Pack played deep into the postseason before losing to Youngstown State.

“Those teams, to me, were the most fun,” says Santoro, who began covering Nevada football in 1988. “People don’t give them enough credit. They think that because now they’re in Division I [generally accepted as college football’s highest level], (today’s) teams are automatically better. That’s not true. There are a lot of guys on those ’90, ’91 teams that could play now—that (UNR) wishes they had now.”

Ault doesn’t disagree.

“Well, some of (the Divison II players) could,” he says. “I mean, they’d be very competitive. The early ’90s teams were pretty doggone good.”

Ault left his coaching job at Nevada after the 1992 season only to return in 1994 and ’95, when he led the Wolf Pack to record-breaking offensive years throwing the ball. He remained the school’s athletic director, a distinction he held until 2004.

Pistol Fires

After nearly a decade away from coaching, Ault couldn’t resist the call of another run with the Pack.

“The president asked me if I’d like to come back in and I said, ‘Yeah, I sure would. I want to end my career doing that,’” says Ault, adding that Nevada was “very average” by the time he returned in 2004.

That’s when Ault began tinkering with the first concept of the pistol offense.

“We had to do something because our football program had fallen off dramatically,” Ault says. “So, for one, I wanted to reinvent myself. And two, I wanted to try to give our program something we could call our own, something that nobody else was doing. And that’s how the pistol came about.”

To create the pistol, Ault essentially married the spread passing offense associated with the shotgun with the power running game. Instead of the quarterback lining up six yards behind center, however, he lined up only four yards back, while the running back, normally to the side of the quarterback in the shotgun, stood directly behind the quarterback, hidden from defenders as he began moving up field.

“The thought process was that it would be a great offense to run downhill—if it worked. The problem I had was there was no film on it, there was no one to talk to, there was nobody doing it. So it really was us. It’s ours. We spent the time developing it. And I’ve probably made every mistake in the world with it. But that was special, and it separated us,” Ault says.

Much of the pistol’s early success hinged on whether Nevada quarterback Jeff Rowe, a former star at Reno’s McQueen High School, could handle the new offense when it debuted in 2005. He did, largely because Ault was careful not to force feed the junior quarterback too much of the new system at once, Rowe says. Plus, Ault added, he and offensive coordinator Chris Klenakis were still creating elements of the pistol on the fly.

“Really, it was just a different formation, and then we ran our same offense. So it wasn’t like we threw this whole new offense together,” Rowe says. “And then once we did that we realized the running advantage. And then from there it has evolved slowly over time. So the learning curve really wasn’t all that much.”

Simplified or not, Ault credited Rowe for running the new offense without a hitch. In 2005, the first year running the pistol, Rowe earned second-team All-WAC honors while the Wolf Pack finished 21st in the nation in total offense, averaging 264 yards per game. Running backs B.J. Mitchell and Robert Hubbard carried much of the load as well during that 9–3 2005 season, which Nevada capped with a 49–48 win over Central Florida in the Sheraton Hawaii Bowl.

“Jeff is a legit legend, because he was the first pistol quarterback ever. He was the key,” Ault says. “If Jeff couldn’t do it, then I knew that it just wasn’t going to work.”

A new bullet

While Rowe ran the pistol his senior year, in 2006, a lanky quarterback with speed and raw athleticism named Colin Kaepernick watched from the sideline as a redshirt freshman. Kaepernick, also a standout pitcher in high school, remained a work in progress, with a strong arm but a strange football throwing motion.

A season-ending foot injury to then-starter Nick Graziano pressed Kaepernick into the starting role his freshman year. He enjoyed immediate success, throwing for 384 yards and four touchdowns after entering the Fresno State game in the second quarter.

The pistol became an even more lethal weapon in Kaepernick’s sophomore season, 2008, when Ault added an option element to the offense. Kaepernick placed the ball in the gut of the running back before deciding at the last moment, based on the defense, whether to hand it off or keep it himself around the end.

It worked. Kaepernick, now a Super Bowl quarterback for the San Francisco 49ers, was named WAC Player of the Year after becoming the fifth player in NCAA history to exceed 2,000 yards passing (2,849) and 1,000 yards rushing (1,130) in the same season. He went on to finish his college career with 4,112 yards rushing on 600 carries, with 59 touchdowns. He threw for 10,098 yards on 740-for-1,271 passing, with 82 touchdowns and 24 interceptions.

“It’s funny, everybody thinks we put the read (option) in because of Colin. But that was just part of the system. We went three years without running any of the read, and that was going to be the third stage of the pistol offense for us, no matter who was at quarterback,” Ault says.

“I felt like once we got proficient at the actual pistol formation, we could add the read and get ourselves some quarterbacks who are fairly good at running it. But it would just be part of the offense, really a changeup more than anything else. And with Kaep, it covered up some of his throwing at the time, because he wasn’t a quality thrower then. And the rest is history.”

Although some college programs caught on to the pistol after it debuted at Nevada, it wasn’t until the Wolf Pack’s 2010 season—when Kaepernick led the team to a 13–1 record and No. 11 national ranking—that the pistol gained steam nationally.

“It was always a big deal here. Right from the start we knew it was something new,” Santoro says. “But it wasn’t until probably 2010 that it started to sweep the nation. It came with Kaepernick and the year he had. That’s when it kind of went crazy.”

49ers head coach Jim Harbaugh, then in his final year at Stanford, even made a trip to Reno with his staff to learn more about Ault’s creation.

“They all came up and studied the pistol for about three days with us. So they had it in their notes, and I’m sure when they drafted Kaep they probably thought, ‘One day we might revisit this thing and see what will happen.’ And lo and behold, there it is,” Ault says.

The legend continues

Ault’s career may be far from over.

“When I stepped down at Nevada, I was real clear to say, ‘I’m not retiring.’ I said I was stepping down,” Ault says. ”

Whether he chooses to work in pro football for another couple of years or ten, the hard-nosed quarterback will never escape his label as the man behind the pistol offense. He’s fine with that. His three-decades-long resume speaks for itself.

“There’s no question that Ault’s offense for the 28 years he was head coach was one of the best in the country,” Santoro says. “I know he gets a lot of credit for the pistol, but I don’t think he gets enough credit overall for what his offenses have done his entire career. They were pretty amazing. They never had a bad offense. They were always good to great.”

Boise State’s Petersen sums it up: “He is truly an innovator of the game.”

Sylas Wright is a Truckee-based sports writer.

No Comments