22 Dec All Eyes on Tahoe’s Echo Summit

The Civil Rights Movement, the fastest men on the planet and an unlikely track formed an unforgettable summer in South Lake Tahoe

Imagine a state-of-the-art synthetic track nestled in the rugged woods above Lake Tahoe, overlooked by fans perched on granite boulders, waiting anxiously for the world’s fastest sprinters to burst from the trees.

The athletes emerge, a churning of legs headed by soon-to-be Civil Rights icons Tommie Smith and John Carlos. While it is Smith who will stand atop the podium in Mexico City weeks later—a gloved fist in the air, his head bowed, Carlos mirroring the gesture at his side—this sunny September day in 1968 belongs to Carlos, who crosses the finish line of the 200-meter dash in world record time.

The moment is just a snippet of the greatness on display for a few short weeks at Tahoe’s Echo Summit, the unlikely site of the 1968 U.S Men’s Final Olympic Track & Field Trials.

“That facility, boy, it was something,” Ralph Boston, a gold medalist long jumper and three-time Olympian, now 75, says of the Echo Summit track. “I have a picture of that track from above looking down, and I’ve always said, ‘That is the most beautiful track I have ever seen in my life.’ And I don’t find a single person who disagrees.”

“To me,” says Smith, now 70, “it was a track with a lot of nostalgia, with all the trees. I’m originally from the country in the backwoods of Texas, so I know trees. But not in the middle of a track.”

Smith is not alone. He and his U.S. teammates experienced an Olympic trials experience unlike any before or since, held on a forested track at 7,377 feet in elevation, at the base of a since-closed ski area and the crossing of the Pacific Crest Trail near U.S. Highway 50.

“It was a magical place,” says Dick Fosbury, Olympic gold medalist high jumper and the inventor of the Fosbury Flop, the standard technique used today. “All of a sudden you’d see a javelin come flying out of the trees. It was a fantasy.”

In the weeks leading up to the 1968 Summer Olympics in Mexico City, South Lake Tahoe buzzed with excitement and drama as it basked in the spotlight as the hub of the track and field universe.

Racial tensions were high, competition was fierce, and many aspiring athletes left in heartbreak, cut from an elite team touted as the best in history. That U.S. men’s team set three world records at Echo Summit (two more were disallowed) and six in the Olympics. The team won 24 medals in Mexico City, including 12 golds.

“We cleaned up in just about every event,” says Bob Beamon, who crushed the long jump world record by nearly 2 feet in Mexico City. “We basically set the standard.”

High Hopes

The Echo Summit trials owe thanks to a man named Walt Little. A former sports editor at the Bakersfield Californian and editor of the Lake Tahoe News, Little became parks director for the City of South Lake Tahoe after it incorporated in 1965. He was a sports aficionado and had connections to some of the biggest athletes and coaches of the time. His close friend was Payton Jordan, the longtime track coach at Stanford University who led the 1968 U.S. Olympic team.

Little’s youngest son Bill, meanwhile, was in high school and working at the Echo Summit ski resort when the U.S. Olympic Planning Commission sought a high-elevation site to host a training camp and trials. Bill helped his father make the connection. Echo Summit was just 28 feet higher than Mexico City.

“They got into a conversation, and Bill said, ‘Well, you know that Echo Summit and Mexico City are almost identical in elevation,’” says Walt Little, Jr., Bill’s older brother. “And my dad started to think about the possibilities, and he called Payton Jordan with this idea, and Payton said, ‘You are insane, Little. When do we start?’ So they started making phone calls.

“It was like an avalanche that started with a little idea and snowballed into what we all know was the greatest team ever created in track and field.”

The U.S. Forest Service permitted the installation of a track under one condition: that it minimally impact the land. Hence the trees left in the middle. Harrah’s Lake Tahoe provided financial support, and a five-cent motel tax helped raise the rest of the revenue needed for the city to buy a six-lane, $260,000 Tartan track modeled after the Mexico City Olympic track.

Athletes began arriving at the Echo Summit training center in July. Trailers went up across the street to house single athletes, while most of the married couples stayed in hotels in South Lake Tahoe. Little and other city officials helped some of the athletes and their wives land part-time jobs in town. Carlos, for example, worked at a casino that summer.

“It was crazy. Unique. It was a big deal, and everybody was on board with it,” says Les Wright, a longtime youth track coach in South Lake Tahoe who worked as one of the long jump officials during the trials. “They had bleachers up there, and they were full. All the track aficionados were up there. I mean, I probably didn’t understand the significance of it myself. I just thought that’s what happened all the time.”

Site for the Ages

The Echo Summit site was a hit with the athletes from day one.

“I’d never been to training camp before, and, of course, no one had ever experienced altitude training at all,” says Ed Burke, a three-time Olympian in the hammer throw and a San Jose State teammate of Smith and Carlos.

“We had trailer houses right there at the summit, and they fed you as much steak as you could eat. I had never eaten so much in my life. You’d get up, probably eat steak and eggs, go lift weights, go lay on the pole vault pit in the warm sun and watch the airplanes go over, because it was such clear blue skies. Then you might go back and lift weights or throw, and then do nothing. I guess that’s what I thought scholarship athletes did.”

Carlos, who was born and raised in Harlem, says he adapted quickly to the mountain setting, which he remembers fondly.

“The first thing I remember about Tahoe is how unique that facility was,” he says. “It was very scenic and relaxing. And then I remember certain times it would snow. I remember the treacherous rides up and down that hill, with all the turns and so forth. And then I remember that it made the team a lot closer. I think the team bonded. It was such a serene atmosphere; I think everyone just fell in love with the place and the situation.”

Along with the trees, boulders were left on the infield of the track. A row of bleachers lined the finish straightaway, seating about 350 spectators. Other fans climbed onto rocks or watched from the sloping hillside. Views were limited, with the start of the 200-meter dash completely obstructed by forest.

“As you left turn one and went into turn two, you were going into the trees,” says Bill Little, who carried an Olympic flag around for all the athletes to sign during the trials. “Turns three and four were totally engulfed in the trees.”

The javelin and hammer throw circles also were shrouded in trees within the track—“You damn near had to aim to miss the trees,” Burke says—and Boston says the long jump runway “came right out of the woods.”

Boston adds, “The pit itself was near the finish line, but you came out of the forest down this strip of track and into the long jump pit. That was just so neat. I have shown photos of it to athletes of this current generation and they couldn’t believe it. They say, ‘Where is that? I’d love to train there.’”

Bob Beamon with a record leap in Mexico City, photo courtesy International Olympic Committee

Center of Attention

The 1968 trials attracted significant media coverage. Not only were the nation’s top athletes clashing for coveted roster spots—and setting records in the process—the Civil Rights Movement was at its peak, and talks of the black athletes boycotting the Olympics created a firestorm of discussion heading into the trials.

Smith and Carlos were at the center of the controversy. Along with noted sociologist Harry Edwards, the two San Jose State students helped establish an organization called the Olympic Project for Human Rights, which advocated an Olympic boycott if specific civil rights issues were not addressed. They included banning apartheid-ruled South Africa and Rhodesia from the Games and restoring the world heavyweight boxing title to Muhammad Ali.

“There was a lot of nervous reaction to the politics that Olympic Project for Human Rights brought,” Smith says. “The black athletes were from all different parts of the country. Some were from the North, some were from the South, some were from Central California like myself. We were different from the Southern guys, because the Southern guys could not do what the Northern guys and California guys did socially. So they had to be a little quieter and not get out of hand for any reason because they had to go back home. So they had to be very careful, and they were, too.”

The black athletes on the U.S. team held a meeting and voted on whether or not to boycott, Smith says.

“It was decided that each athlete would represent himself at the Olympic Games the way he thought his country represented him. So that freed all the athletes up to do what they wanted to, or nothing. And there was no dissension among the athletes if they did nothing.”

Initially, Carlos was disappointed with the outcome of the vote, he says. He even considered boycotting himself. “But then God injected in my brain that if you stay home, when America is demonstrating track and field, who’s going to represent you?” Carlos says.

With the vote settled and the boycott off the table, the athletes next had to worry about making the cut on the stacked U.S. team. As Boston says, the Echo Summit trials featured “a who’s who of track and field.” Then and future Olympic gold medalists included Lee Evans (400 meters), who combined with Smith and Carlos to create a dominant sprinting trio at San Jose State, as well as Fosbury, Beamon and Boston, Tommy Hines (100 meters), Willie Davenport (110 hurdles), Bill Toomey (decathlon), Al Oerter (discus) and Bob Seagren (pole vault), among others.

Steve Simmons, who attended the trials as a spectator before later becoming a U.S. Olympic coach, recalls the competitive atmosphere overriding the racial tensions of the time.

“Everyone was just trying to make the damn team,” Simmons says. “The white guys knew that there was upheaval in the country; everybody knew that. And everybody knew that there had been talk of boycotting by the blacks. But the deal was, you can’t boycott a team unless you’re on a team. First you have to make the team, and making that team was like robbing Fort Knox. It was tough. You had to set world records out there to get on that team.”

Records Fall, Hearts Drop

While the thin air of Echo Summit slowed the distance runners and impacted some athletes negatively—Simmons remembers hurdler Russ Rogers passing out and hitting his head after a race, while endurance specialist (and future U.S. Congressman) Jim Ryun struggled with the elevation throughout the trials—many of the sprinters and jumpers excelled.

Seagren cleared 17 feet, 9 inches to set a world record in the pole vault, and Geoff Vanderstock set a world record in the 400-meter hurdles with a time of 48.8.

Evans and Larry James, meanwhile, both posted world-record times in the anticipated 400-meter dash final, Evans with a mark of 44 seconds flat and James in 44.19. Both marks eclipsed the record set by teammate Vince Matthews earlier that summer at Echo Summit.

James was awarded the win and world record, however, while Evans’ time was disallowed because he wore Puma “brush spikes,” which consisted of 68 small needle spikes. International rules allowed only eight spikes. Evans, this time wearing legal spikes, upped the bar again in Mexico City, setting a new world record at 43.86 with a gold-medal performance.

Carlos wore the same illegal brush spikes in his winning 200-meter final. As a result, his world record time of 19.7 seconds was removed from the record books. Carlos believes that his outspokenness prompted officials to deny his record.

“Oh, without a doubt. I smashed the record and I believe that based on my political views, I never got credit for it,” Carlos says. “But I’m satisfied. I know I did it, God knows I did it, and I can live with it.”

For all those who went on to compete in the Mexico City Games, more than a few Olympic hopefuls left Echo Summit in heartbreak.

The Echo Summit trials were actually the second trials held that summer, the first of which took place in Los Angeles in late June. Because there were two separate trials, qualifying criteria was unclear. It wasn’t until the Echo Summit trials that the athletes learned that only results from Echo Summit would be used.

“They originally thought the trials were in L.A., so certain guys thought they had already made it,” says Bob Burns, a history buff on the 1968 trials and author of several articles about the event. “Right before Echo Summit, they (the USOC) said, ‘This is it.’ There were a number of guys who were pretty pissed off about it.”

Smith suspects the USOC added the extra trials competition in an attempt to weed out “the troublemakers.”

“If the USOC was trying to get some of us disqualified by having an extra meet, it didn’t work. In fact, it worked in the reverse,” he says. “It made us stronger and made us more competitive.”

The second trials may have benefitted some, but not Dave Patrick or John Hartfield.

Patrick thought he secured a spot on the Olympic squad after winning the 1,500-meter run at the semifinal trials in L.A. He placed fourth at Echo Summit and did not make the team.

Hartfield led the high jump after clearing 7 feet, 2 inches on his first attempt. The next three jumpers, Fosbury, Ed Caruthers and Reynaldo Brown, all cleared 7-3 for the first times in their careers, and Hartfield failed on all three attempts to finish fourth, one spot away from an Olympic berth. Boston remembers Hartfield disappearing into the forest crying, his pregnant wife chasing after him.

“You had the cream of the crop, and it was like a war out there. It was cutthroat,” says Simmons. “And when your final came up and you didn’t make it in that top three, they sent your butt home the next day. They’d give you your plane ticket, drive you down to Reno, and you were out of there.”

History in the Making

Echo Summit was only a preview of the history that would be made in Mexico City in October 1968—both on the track and podium.

The U.S. men’s track and field team carried its competitive edge into the Games, setting another six world records and earning 24 medals, 12 of them gold. Combined with the U.S. women’s team, whose high-elevation training was held in New Mexico and its trials in Walnut, California, the U.S. track team won 28 medals, including 15 golds.

Beamon, who won the long jump at Echo Summit with a leap of 27 feet, 6 inches (Boston was second at 27-01), shocked the world with a monstrous jump in Mexico City. He demolished the previous record—of 27 feet, 4 ¾ inches, held by both Boston and Soviet jumper Igor Ter-Ovanesyan—by almost 2 feet, soaring 29 feet, 2 ½ inches.

“Well, I surprised myself,” Beamon says. “I jump to win, not to break any records—just whatever it took to win. But I didn’t expect that.”

Sprinter Jim Hines, also notched a World Record for the Americans in the 100 Meter Dash, becoming the first man to ever break the 10-second barrier, a feat once deemed impossible.

Smith and Carlos were set up for a showdown in the 200-meter finals. And while Carlos had his day at Echo Summit, Smith had his in Mexico City. He raced to victory in world record time, crossing the line in 19.83 seconds.

What most did not know, however, is that Smith accomplished the feat with a pulled groin muscle suffered while slowing after his semifinal heat. A student of the human anatomy, he adjusted his gait in the final heat to compensate for the injury.

“I was in fourth place mid turn. I was in bad shape,” Smith recalls. “By the end of the turn, I was in third place. Once we got on the straightaway, I knew that I would be okay as long as I could keep the knees up, keep the toes in and keep the stride about the same length, but using the right leg more than the left, and using the left leg more as a support leg than a power leg. It was the first time I ran with a Bob Hayes–type stride. Bob Hayes kind of ran with a surge in his stride. The last 40 meters, that’s how I ran.”

Still 10 meters from the finish, Smith raised both arms in celebration and broke into a smile as he crossed the line. Australian Peter Norman took silver (20.06) and Carlos bronze (20.10).

As thrilling as the race was, it was the medal ceremony that proved memorable.

The podium finishes by Smith and Carlos provided them the grandest forum of all to express their message. They had been told by the USOC not to bring a political issue into the Olympic Games. They ignored the warning.

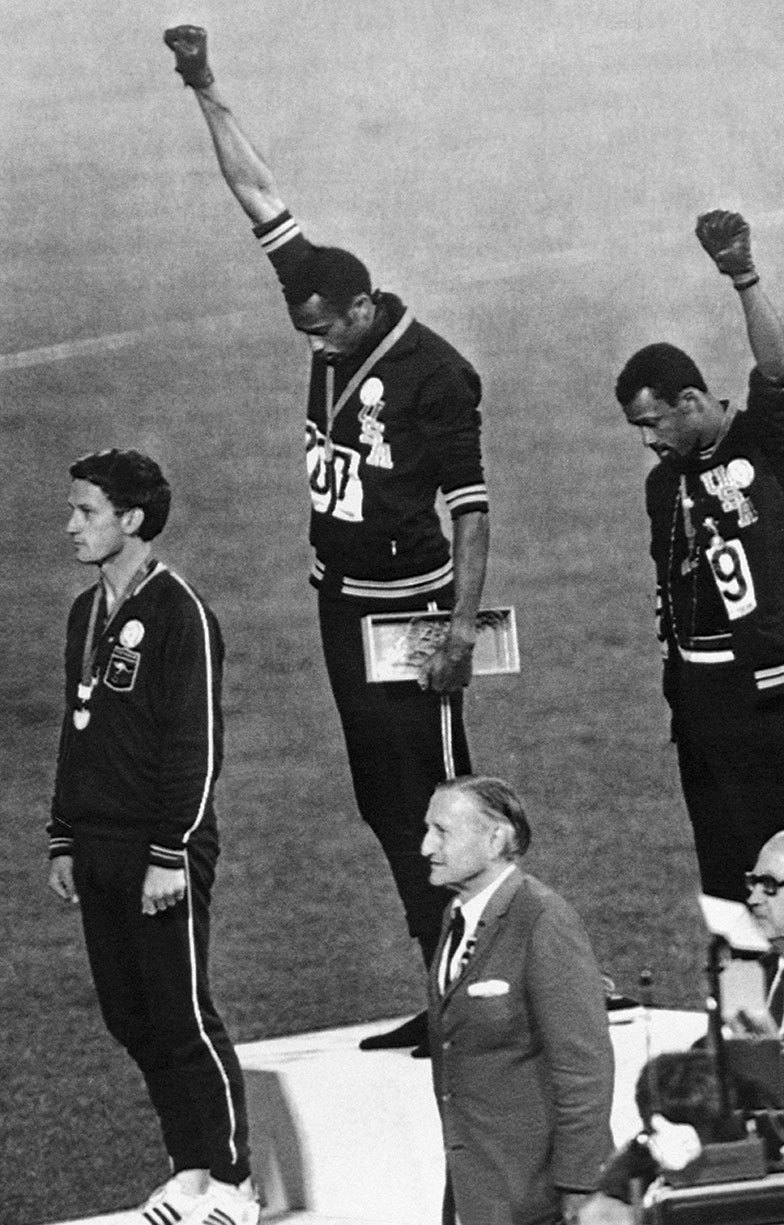

Tommie Smith (center) and John Carlos (right) won gold and bronze in Mexico City, and raised their fists in

solidarity with oppressed African Americans in the U.S., photo courtesy International Olympic Committee

During the ceremony, Smith and Carlos each raised a black-gloved fist—a symbol of Black Power—and bowed their heads as they turned to face the American flag for the playing of the Star Spangled Banner. Each wore only black socks to the podium to represent black poverty, while Smith, Carlos and Norman all wore Olympic Project for Human Rights badges.

They were booed as they left the podium.

“I had made up my mind a long time ago based on incidences in my life that there were very serious social problems that we needed to try and deal with, and the only way to do that is to bring attention to it,” Carlos says. “And in my estimation, there was no greater arena than the Olympic Games to bring attention to it. I’m glad I had the opportunity to go to the Olympics, because to me it was a stepping-stone to bring attention to the social issues we had to deal with.”

At the urging of International Olympic Committee president Avery Brundage, the USOC suspended Smith and Carlos from the team and banned them from the Olympic Village. They were also barred from international competition, essentially ending their track careers. Both went on to play briefly in the National Football League.

“That was the most monumental sacrifice and poignant moment in the Civil Rights Movement,” says Burke. “I think for the entire world, that was the keystone moment in civil rights and the fight for more fairness in sports. They gave more than I think they even had any idea.”

Carlos says the USOC threatened to strip both his and Carlos’s medals, but never did.

“What they did was they came to us and tried to intimidate us, saying they were going to take our medals. I told them it was absurd what they were talking about. So what they did was they actually backed away, but they told the world for 46 years that they had taken our medals away. They told the world that to intimidate any young individuals. It was a total lie.”

Timeless Track

Back at Echo Summit, the portable Tartan track was peeled off that fall, rolled into sections and stored over the winter. The next summer, it was hauled down the mountain to South Lake Tahoe, where it was installed at the middle school.

It remained at the school for nearly 40 years before the weathered surface was replaced.

“We had it down there for years and years, and we had the best track in the state of California,” Wright says. “It was an original Tartan surface. I considered that my track. I was possessive and made sure everyone took care of it.”

As for the 1968 U.S. Olympic men’s track team, Burke says the members convened for a 30-year reunion in New Orleans in 1998. It was then, he says, that the team truly came together.

“Steve Simmons arranged the reunion, and there, all of us, black and white and all in between, sat in a room and had cola and beer, and sat on the floor and the beds and talked about those times,” Burke says. “I think that was the true team-building—there was a bonding, but it took time. We lived through something that was huge. It bound us. But it didn’t bind us at the moment.”

Intrigued by the history, Burns, who attended the Echo Summit trials for one day as an 11-year-old, spearheaded an effort to designate the site as a California Historic Landmark. He received support from the U.S. Forest Service, Eldorado National Forest and California Parks Department. Plans are in the works for a June 27 dedication ceremony.

The Echo Summit site is now a sledding area, called Adventure Mountain Lake Tahoe.

“I’m happy to see all the people realize the greatness of that location,” says Carlos. “I’m glad it’s going to be a historical landmark. It really deserves that title.”

Sylas Wright is a Truckee-based writer and sports editor. Bob Burns contributed to this story.

No Comments