22 Jun From Daydreams To Wooden Reality

One local’s quest to reinvent surfing, skiing, soaring and history

Craig Beck doesn’t dabble in hobbies.

When the longtime Tahoe local gets into something, he tends to go all in.

Whether he’s flying homemade hang gliders or working on his latest project—Tahoe Native Surfboards—Beck is passionate about finding harmony between art, design and the natural world. His most recent creations are perhaps the natural evolution of Beck’s interests throughout the years, combining form and function unlike any other surfboards on the market.

Whereas most modern surf and wakesurf boards are made out of a combination of fiberglass, carbon fiber and other high-tech materials, Tahoe Native boards—with their striking solid-wood construction—hark back to a time when classic Chris-Craft and Gar Wood ski boats circled Tahoe’s waters. And while Beck’s handmade creations look worthy of hanging in a museum, riding one will have its user reevaluating the need for all those high-tech materials used by other surfboard manufacturers.

Hand-built by Beck in either his Carnelian Bay or Bear River workshops, Tahoe Native boards are all crafted from 100 percent vertical-grain Douglas fir personally selected from local lumberyards for quality and beauty.

“Every piece of wood has a different grain. So depending on how you combine those, each board comes out differently,” Beck says from his Carnelian Bay workshop. “I love that process and that you can take this really pretty piece of art and ride it… It’s really cool.”

Beck’s son, Dave, wakesurfs on Lake Tahoe on a Tahoe Native board, photo by Ryan Salm

Beck’s son, Dave, wakesurfs on Lake Tahoe on a Tahoe Native board, photo by Ryan Salm

Learning to Ski at the Olympics

Those who know Beck are not surprised that he taught himself how to make surfboards out of natural materials. Beck has long been inspired by the natural world and has made a name for himself as an innovator with a keen eye for history.

The son of an Air Force pilot, Beck and his family lived all over the world while he was young—from Southern California to Japan, England, Germany and Ohio, before landing in the Lake Tahoe region in 1959, just in time for Beck to enter Truckee High School as a freshman.

That winter, at the urging of a school friend, Beck took a job as a ski messenger transporting film for the news crews covering the 1960 Squaw Valley Olympics—despite the fact that he didn’t know how to ski.

“My first run was right up on top of the Palisades,” Beck recalls. “I had never skied before. Everyone else heading up there were athletes—really big guys—and here I was this little skinny 14-year-old, and I was just really frightened.”

Beck’s first assignment: Bring film from the start of the men’s downhill to the base of the resort, where photos would be sent out via news wires to media outlets around the world. And so, by emulating the turns he saw other skiers making down the mountain, Beck made it down his first run, and a lifelong passion was born.

Beck dove into the ski lifestyle, becoming an expert skier and a regular among the small scene of diehard powder hounds hanging around Squaw Valley and Alpine Meadows. And, in perhaps his first major innovation, he became a pioneer in Tahoe ski filmmaking with the 1975 release of Daydreams—one of the first films in the world to showcase the budding extreme ski culture nurtured in the Lake Tahoe region.

Mark Rivard front flips off the Palisades at Squaw Valley in a scene from Daydreams in 1974. Beck says Rivard broke both legs upon landing the roughly 120-foot drop, courtesy photo

“He really did reinvent skiing and ski movies back in the day,” says his son, Dave Beck. “Warren Miller was around back then, but he wasn’t doing what my dad was doing. There were no movies like Daydreams at the time. He put the skiing to music in an artistic way and took a lot of the talking out… And he was featuring guys who weren’t getting paid to do it. They were rebels and it was all just for the love of the sport.”

A self-taught videographer and editor, Beck took a childhood interest in cameras and photography, combined it with as much information as he could glean from reading books on moviemaking, and self-produced Daydreams in his living room, mastering the tricky process of multi-track editing before digital technology was available.

Former professional skier and longtime local ski cinematographer Tom Day sees many of the seeds of today’s action sports movies in Beck’s film.

“I can still put Daydreams on and get inspired,” Day says. “I think Craig was ahead of his time when he made that film. As far as the skiing went, he really captured the extreme exploits here at Squaw Valley… What people are doing today all kind of stems from how Craig really fired it up in Daydreams.”

A young Craig Beck flies a hang glider he built in his living room, courtesy photo

From Ski Films to Soaring

After a successful film tour throughout the western United States, Japan and France, one might think Beck would cash in and try to repeat a winning formula a couple more times. But Beck’s drive for do-it-yourself innovation had already pushed him to his next adventure—flying.

“He always seems like he has a project, something he’s really into,” says longtime friend Alex English. “His dad was a pilot and flew experimental airplanes and things like that, so it probably just runs in the family… Tinkering, making things work better, and building things you can’t find.”

Hang gliding, which Beck first got hooked on by building a glider in his living room, had him once again reading everything he could get his hands on about a subject—this time aeronautics and wing forms.

“It was a terrible glider that crashed so many times,” Beck says of his homebuilt prototype, “but it flew.”

In typical Beck style, years of tinkering with designs ultimately led to handmade gliders that performed as well as anything else on the market; Beck built them for friends and other glider pilots when he wasn’t selling homes as a local real estate broker or building them as a general contractor.

Beck stands with his homemade “Whitehawk” glider, courtesy photo

Back to the Slopes

Beck’s next passion—reviving the longboard ski races of the 1800s—was fueled by his love of ski history and tales of legendary Tahoe mountain man Snowshoe Thompson. At the urging of 93-year-old Bill Barry—then the oldest living journalist in Nevada—Beck began organizing traditional longboard races.

Back in the Gold Rush days, racers strapped 10- to 15-foot-long wooden skis with no metal edges to their boots with leather straps for bindings, and—fueled by a mixture of whiskey and determination—reached speeds of over 90 miles per hour down a straight course. These true historical tales had Beck’s mind buzzing with possibilities.

“When I had my first race up in Johnsville [California, in Plumas-Eureka State Park], a couple of guys brought these museum skis to the races and they ended up smashing them at the bottom and ruined these skis,” Beck says. “So I said, ‘Hey guys, you’ve got to start building your own skis.’”

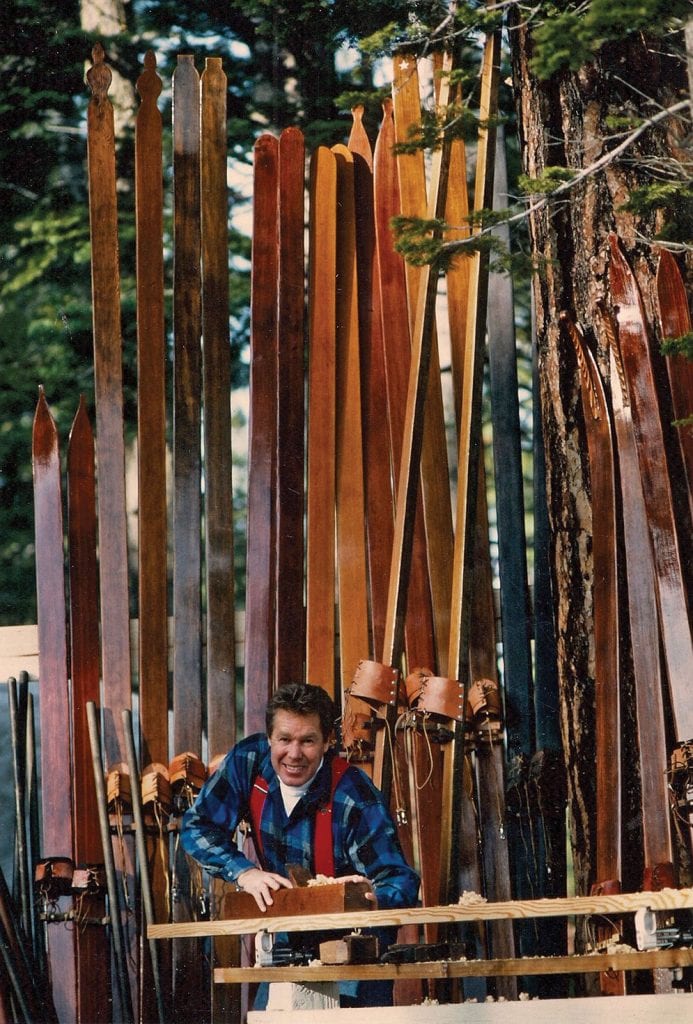

One of Beck’s passions over the years was building longboard skis like the ones used for racing in the 1800s, courtesy photo

In true Beck style, he took it upon himself and ended up building 40 to 50 pairs of authentic longboard-style skis—using the same vertical-grain Douglas fir that would later go into Tahoe Native Surfboards—and went on to teach local speed skiers and pros how to race on them at national championship events held around the Tahoe region, as well as the World Championship Longboard Races held at the Plumas-Eureka Ski Bowl in Johnsville.

“He started making those wooden skis and we’d go out and race those in the mid to late 1990s,” English says. “We’d go up to Johnsville Ski Area and race, or up to some of the resorts on Donner Summit to race. It was a hoot. People would show up in their old-timey clothes and everybody had their own secret wax.”

Beck’s son remembers being carted around to the longboard races as a child along with a cadre of world-class athletes and numerous pairs of handmade wooden skis his dad had built in his workshop.

“I grew up skiing and was just a little rug rat following my dad everywhere,” Dave Beck says. “He’d put on these [longboard] events and I didn’t think much of it, but he’d take me along and it was really cool.”

Beck’s willingness to almost singlehandedly resurrect this lost sport garnered the Beck family an invitation to put on a longboard demonstration at the 2002 Salt Lake City Olympics, and revived interest in this original Lake Tahoe “extreme” ski competition.

Beck tests his longboard skis at 60 miles per hour, courtesy photo

Hawaiian inspiration

Building surfboards out of wood is by no means a new idea. Beck was inspired by images he saw of the early Hawaiian surfers, riding waves on 15- to 18-foot longboards. But what Beck learned through his research was that it was mostly Hawaiian royalty and other bigwigs who were allowed to surf those huge boards.

What Beck saw was something different—a smaller wooden board called an “alaia.”

“I saw this article with a picture of these old Hawaiian guys surfing on these little boards,” Beck says. “So I did a little research on them, found some example designs, toured a few museums in Hawaii, and figured it would be pretty cool to make one of these things, just for historical purposes.”

And thus, the latest seed was planted in Beck’s mind, resulting in a familiar pattern of tinkering in his workshop—gluing, shaping and playing with different wooden forms for surf and wakesurf boards.

Living in Carnelian Bay, it was only natural for Beck to try out his wooden designs behind a boat on Lake Tahoe rather than drive four hours to an ocean surf break. In 2011, Beck and his crew of riders first tested a board he called the “Claybo,” which featured a concave bottom and wooden runners along the underside of the rails.

“We got on that one and it was just like a new sport,” Beck says.

Beck works on his Tahoe Native Surfboards in his Carnelian Bay shop, photo by Ryan Salm

Beck works on his Tahoe Native Surfboards in his Carnelian Bay shop, photo by Ryan Salm

Innovations came quickly, with new features such as sidecut (borrowed from ski design), reverse hydrofoil (to float the nose of the board), a definite edge along the rails (to allow more of a snowboard-like carving ability on water), fins in different patterns, and interesting flex patterns (something only a wooden board can do).

“We’re breaking all the rules of surfing, and we’re going with the laws of physics,” Dave Beck says of his father’s designs—noting that the handmade nature of the boards and natural materials used were the inspiration for wrapping them under the umbrella of the Tahoe Native brand, which Dave and his wife, Camille, started as a way of celebrating the local culture in the Lake Tahoe region.

And while the chance to forge ahead with new conceptions of a historically significant design satisfied Beck’s need to create, it was the ease with which everyone was able to surf the boards that gave the father and son the idea of building a business around them.

“From day one, everybody got up the very first time on one of these boards,” says Beck, who also builds Tahoe Native skateboards.

Dave—who also serves as lead test rider—is more effusive with his praise: “He’s reinventing the surfboard. It’s like a parabolic ski versus a straight ski. It’s like night and day.

“For my mom and my family, it’s kind of a joke. He’s been carving these things for about 10 years. And I finally talked him into getting them out into the world. He likes to keep things for himself; he’s a true artist. He likes to build it and then keep it in his garage.”

Beck, his son and their close-knit group of test riders who’ve gotten to experience Tahoe Native Surfboards on Tahoe or in the ocean are excited to continue pushing new boundaries.

Dave has plans to ship boards over to Hawaii to let some big-wave surfers try them out at the legendary Jaws surf break of the north shore of Maui, and English is hoping to convince Beck to allow him to experiment with new ways of riding a hydrofoil board that Beck built out of old hang glider parts.

One thing everybody in the crew expects to see soon is more Tahoe Native boards out on Lake Tahoe as word gets out that Beck is actually selling them.

“Everybody loves them,” English says. “We’ll go walking down the docks to get on the boat and people stop us to look at the boards as we’re walking. It’s pretty universal, because they’re so different. The combination of a pure, custom, handmade wooden board with beautiful artwork on there… Who wouldn’t want to have one?”

One of Beck’s favorite things about his latest passion is that the Tahoe Native brand is truly a family affair: Craig splits his time between his Carnelian Bay and Bear River workshops, building custom boards for customers he gets mostly by word of mouth.

Dave Beck and his wife are working on a complimentary swimwear and apparel line that emphasizes the same local-first ethos that makes the surfboards so distinctive.

And Craig’s wife, Cindy, is working behind the scenes keeping everything together.

Beck’s ultimate goal for Tahoe Native Surfboards? To reinvent the surfboard.

“The first goal is to make the most eco-friendly surfboard out there; and working with wood, I can do that,” he says. “I also want to build a really high-performance surfboard that sets a new standard in the industry.”

Beck builds his Tahoe Native Surfboards from high-quality Douglas fir selected from local lumberyards. After hand-shaping the boards, the artwork is carefully painted on before eight to 10 coats of varnish are applied, photo by Ryan Salm

Beck builds his Tahoe Native Surfboards from high-quality Douglas fir selected from local lumberyards. After hand-shaping the boards, the artwork is carefully painted on before eight to 10 coats of varnish are applied, photo by Ryan Salm

The Tahoe Native Surfboard construction process

• First, a customer picks out the shape and artwork he or she would like on the board.

• Next, Beck visits local lumberyards, looking for six to eight pieces of the best vertical-grain Douglas fir available.

• The wood is glued together into a large plank, with a second layer of wood added for rails and reverse hydrofoils on the tail. At this point the board weighs around 25 pounds.

• Beck then draws on the shape and cuts it out roughly with a jigsaw. Then the hand-shaping process begins—several hours of hand-planing and sanding until the board is perfect.

• Finally, the artwork is carefully painted on before eight to 10 coats of varnish are applied, with 24 hours of drying time needed in between coats.

• Two or three weeks after the order is placed, a brand-new Tahoe Native Surfboard is ready to be ridden or hung on a wall as a functional piece of art. Beck hopes it will be ridden.

Learn more about Tahoe Native Surfboards.

Paul Raymore is a Truckee-based writer who feels lucky to be able to live, play and raise a family in the Tahoe area. He hopes to someday have a quarter of the crazy stories that Craig Beck has to tell.

Phil Rafton

Posted at 21:35h, 04 FebruaryCreative genius, that’s how I remember Craig. No matter what he is doing, he his going to take it to a new level. Many fun times with him a long time ago. Hope he and Cindy are doing well.