22 Jun Dropping in on a Desert Oasis

Scratching a summer itch to shred at Nevada’s Sand Mountain Recreation Area

It’s mid-August, there’s not a snowflake in sight, but once again, we’re strapping in. Wishful thinking about snowboarding just isn’t enough for freaks like us.

Driving east from Fallon on lonely U.S. Highway 50, you can’t miss the glowing contours of Nevada’s Sand Mountain. The 600-foot-tall sand dune appears out of nowhere like a ghostly apparition of the desert. Its shape shifting, wind-sculpted ridges glimmer against the otherwise dark and rocky Great Basin landscape like an oasis scene stolen from the Sahara.

The 600-foot-tall Sand Mountain stands out against the otherwise dark and rocky Great Basin landscape off U.S. Highway 50, photo by Seth Lightcap

Turns out Sand Mountain’s supernatural vibes are not just surface deep. Wild native folklore and wondrous natural history tell the story of this unique geological phenomenon.

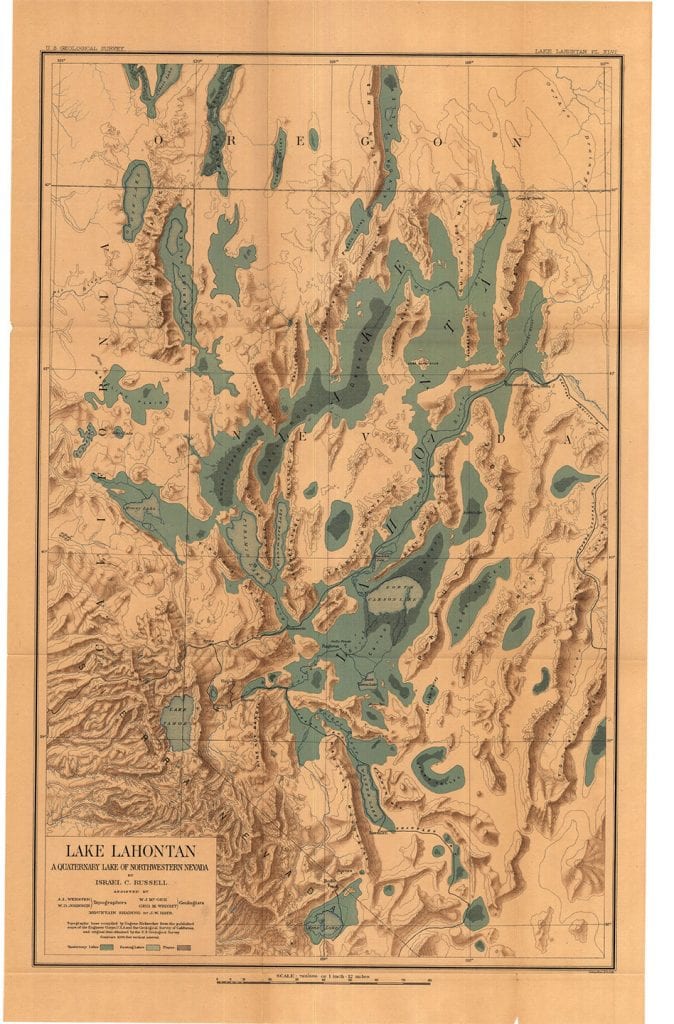

Sand Mountain was formed 9,000 years ago as the ancient Lake Lahontan dried up. Lake Lahontan was an 8,500-square-mile body of water that stretched across the northwest corner of Nevada, connecting Walker Lake with Pyramid Lake and extending north past Winnemucca. Lake Lahontan was one of the largest lakes in North America at that time, and was the native home of the famed Lahontan cutthroat trout.

Map of the ancient Lake Lahontan (1883), courtesy Mary B. Ansari Map Library, University of Nevada, Reno

Scientists speculate the lake level dropped at the end of the Pleistocene Epoch, leaving behind only Walker and Pyramid lakes. The majority of the former lake basin became arid, open playa like the Black Rock Desert. As the deserts grew, blowing sand began collecting ever so elegantly in a protected basin in the surrounding Stillwater Mountains. One perfect grain of silica at a time, the deposited sand slowly formed the rolling dunescape that is Sand Mountain.

The Paiute-Shoshone Native American tribe views Sand Mountain as a sacred site. Their beliefs focus on Sand Mountain’s unique designation as a “singing dune.” When the wind blows against Sand Mountain’s especially fine and uniform sand grains, a loud humming or booming can be heard. Sand Mountain is one of 35 singing dunes in the world. The Paiute-Shoshone believe the singing is the hissing of Kwansee, an ancient serpent that was believed to have lived with their people in the Stillwater range. When Kwansee’s wife died, he was so distraught that he entombed himself in the sand, where he remains to this day, mourning and moaning for his mate.

Now, Sand Mountain is best known as a mecca for desert motorsports. The dunes provide epic terrain for motocross bikes, sand rails and dune buggies, with upwards of 50,000 visitors twisting a throttle at the Sand Mountain Recreational Area each year.

The first time I drove past Sand Mountain, however, it was dawn on a stormy winter morning and there was no sign the peak was such a playground for off-highway vehicles (OHVs). Multiple days of heavy wind and rain had reset every inch of the dune surface to a clean canvas. Without the typical tire tracks, Sand Mountain’s summit ridge looked like a snowy powder face bisected with clean spine lines. As I blazed by on the highway en route to my backcountry snowboarding destination, I mind-surfed the sand spines, thinking how cool it would be to someday slash tracks down that mountain face. But not moto tracks. I wanted to ride the lines on a snowboard, or better yet, a sand board.

A couple years later, on an unseasonably cold Tuesday in August, an overwhelming desire to snowboard brought Sand Mountain back to the center of my attention. It felt like fate when a Google search revealed that Tuesday and Wednesday were free-entrance days. Normal cost is $40 for one to four days, or $90 for an annual pass to the Sand Mountain Recreation Area, which is run by the Bureau of Land Management.

Within two hours of leaving our house in Truckee, my wife, Allison, and I stood at the base of Sand Mountain, beat-up snowboards in hand, fired up to shred some backcountry sand. We hiked to the top of the dune in about 45 minutes. At first we hiked in our snowboard boots, but soon we found that hiking barefoot was blissful with the fine sand swishing between our toes. A couple dune buggy drivers cruised by to say hello. Thankfully, they were some of the only OHVs on the mountain that day.

Just like a winter powder day, Allison Lightcap finds a fresh line on the south face of Sand Mountain, photo by Seth Lightcap

Just like a winter powder day, Allison Lightcap finds a fresh line on the south face of Sand Mountain, photo by Seth Lightcap

Sand Mountain’s summit ridge varies from sidewalk to footprint width. Walking along the ridgeline gives you the feeling of traversing a narrow snow crest, but without the exposure. Broad side ridges intersect the summit ridge at a few spots and the sand surface shows signs of the minor aspect changes, just as snow would. On the northern lee side, the sand was dry and loose. On the windward south side, it was densely packed and still moist. For our first run, we chose the steepest north-facing panel with the hope that the dry sand would be faster and less sticky than the wet sand.

Dropping in delivered equal parts thrill, satisfaction and realization. The thrill came first as our boards lurched into the fall line, gradually picking up enough speed to begin making turns. Until then, we didn’t know if an old snowboard with a standard P-Tex base would even glide on sand. Commercially produced sand boards are made with dense formica, plastic or wood bases for less friction. Satisfaction washed over as our hunch paid off. A beat-up snowboard can shred sand, at least well enough to feather a few turns and feel the wind in your face.

Halfway down the dune, the joyride was mostly over as the slope kicked back and the clumpy sand in the OHV tracks started grabbing at our board edges. This was when the realization hit: Sand boarding is plenty fun, but it doesn’t quite match the thrill of snowboarding—unless one is accustomed to snowboarding in sticky, hot pow. It feels like your board wants to give into gravity and keep gaining momentum, but there’s a tenuous battle between glide and grip that your board only momentarily wins.

Allison Lightcap hikes up for another hot lap down to the dunes, photo by Seth Lightcap

Allison Lightcap hikes up for another hot lap down to the dunes, photo by Seth Lightcap

Despite the intermittent struggle for speed, there was no shortage of new terrain to keep us engaged. We spent the afternoon yo-yoing the ridgeline, laying tracks in every bowl as if we were backcountry snowboarding. The occasional face-plant had us picking sand out of our teeth and blowing gritty snot rockets when we finally strapped in for the last run to the car.

Sand Mountain’s dunes were spectacular, and we most definitely scratched our summer itch to shred.

Seth Lightcap is a Truckee-based writer, photographer, snowboarder and mountain biker. Find more of his work here.

No Comments