22 Jun Tracking Tahoe’s Lone Wolverine

Nearly a decade after his discovery, Buddy the wolverine remains an unsolved mystery

On a cold February day in 2008, then-graduate student Katie Moriarty was scanning through images from her 20 remote cameras set up throughout Sagehen Experimental Forest near Tahoe when something caught her eye.

“I think my initial reaction was shock and awe,” says Moriarty, an Oregon State University grad who is now doing post-graduate work at the U.S. Forest Service Pacific Northwest Research Station.

Studying martens, a small relative of weasels that typically move about in trees, Moriarty found herself staring at a picture of a much larger member of the Mustelidae family, one that hadn’t been seen in the Sierra Nevada—or California—since 1922.

It was a wolverine—a stocky predator weighing between 25 and 55 pounds famous for its ornery disposition.

“We first heard it through the grapevine, because Katie wanted someone to validate the identification before she would say anything,” says Jeff Brown, station director at the UC Berkeley Sagehen Field Station, located about 8 miles north of Truckee off Highway 89. “But just about every biologist in the U.S. knew within a day that this photo had shown up at Sagehen.”

Soon after, a large coordinated network of people and resources descended on the region. They set up more cameras, nailed chicken to trees to help collect DNA samples, gathered fur and scat, and looked for any explanation as to how the creature suddenly appeared in the Sierra for the first time in 86 years.

The news made national headlines, and because of the extreme distances to other known wolverine habitats—hundreds of miles for the closest—the discovery incited a wide range of speculation, explanations and even conspiracy theories.

In the ensuing years, the animal continued to show up on remote cameras, racking up thousands of photos and videos and capturing the imagination and concern of the public. He was even given a name, Buddy, and featured in two children’s books—Buddy The Wayward Wolverine and Buddy And The Magic Chicken Tree.

The animal was seen on a Sierra Pacific Industries camera as recently as March 17 of this year.

In spite of all the questions raised and scientific brainpower exerted, however, experts say Buddy, who is now nearing the end of a wolverine’s typical 10-year lifespan, will likely go down in the history books as an unsolved mystery, an oddity that will continue to defy explanation.

But he’s already left his impact on the region, and may have sparked interest that could ultimately lead to more wolverines in the Sierra in the future.

Photo taken of Buddy with a remote camera on December 26, 2014, courtesy Sierra Pacific Industries

Photo taken of Buddy with a remote camera on December 26, 2014, courtesy Sierra Pacific Industries

Scientific Study and Public Reaction

After Buddy’s discovery, the scientific community immediately began trying to figure out where he came from.

DNA results from collected fur indicated that he was likely from the Northern Rockies, with the Sawtooth Range of Idaho—600 miles away—being the closest genetic population to the Northern Sierra.

The research team contacted an expert on isotopes from UC Berkeley named Todd Dawson to try and learn more about the wolverine’s origins and how it may have arrived in Northern California.

“Todd was really curious about hair,” Brown says. “He told his wife when they were heading on vacation, ‘Shave my hair, put it in a zippy [Ziplock bag], and label it Berkeley.’ He did that every time they’d leave a place on vacation, and then he processed his hair. He found he could tell where he had been based on the isotopic signature in his hair.”

Some of Buddy’s hair was sent to Dawson, and it showed that he had been in the Sawtooths of Idaho in his lifetime.

But the question remained: How did he get here?

Elsewhere, wolverines with transmitters have been tracked walking 60 to 80 miles in a day, sometimes traveling up and over large mountains in the middle of winter, with home ranges greater than 500 miles. One GPS-tracked wolverine made a similar-distance trek from the Grand Teton area in Wyoming to the Rocky Mountains of Colorado, Moriarty says.

Some people found the timing of Buddy’s arrival suspicious, linking to the fact that wolverines were being considered for listing under the Endangered Species Act (wolverines were already classified as a California Endangered Species).

“We got accused of planting him here. It was right around the time U.S. Fish and Wildlife was considering listing them,” Brown says.

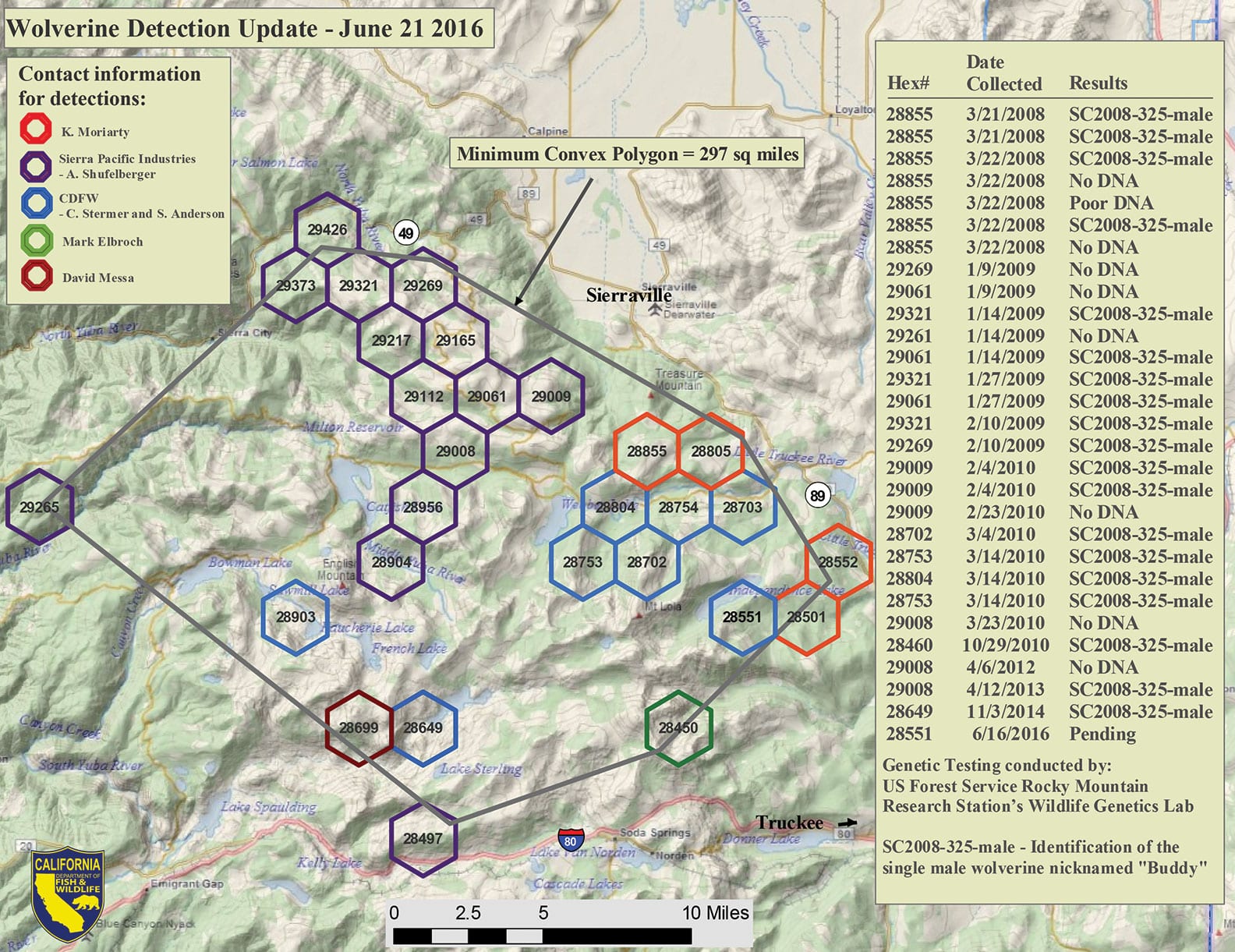

Monitoring wolverine occurrence north of Truckee, map courtesy Chris Stermer, California Department of Fish and Wildlife

Monitoring wolverine occurrence north of Truckee, map courtesy Chris Stermer, California Department of Fish and Wildlife

Unable to definitively determine how the wolverine got to the area, researchers started setting up cameras with bait to get more pictures.

“We had a meeting about a year later,” Brown says. “Do we catch him, tag him? The consensus was it would be awesome to track him, but the risk of accidentally harming him outweighed the benefit.

Brown says his team made the decision to cut back on the amount of chicken they were nailing to trees. “The question was, how much are we modifying his natural behavior if he just has to walk from camera to camera eating chicken?” he says.

As a result, the scientific work wound down and sightings decreased, but public interest continued to grow.

“We had hunters getting in touch wanting to come and kill him; we had people driving up to our gate wanting to see him when we hadn’t even seen him ourselves,” Brown says.

Despite some conspiracy theories and interest in hunting him, most of the public feedback has been positive, says Amanda Shufelberger, a wildlife biologist with the Tahoe District for Sierra Pacific Industries—a timber company with the largest private property holdings in the Sierra Nevada.

“I still get calls regularly from people who want to find out if he’s still alive, if he has a girlfriend, and if they can set up a GoFundMe [a crowdfunding website] to get him a girlfriend,” Shufelberger says. “He still makes the news, and people are still so interested in him.”

Shufelberger, monitoring cameras from Plumas to Placer counties in the Northern Sierra, has amassed thousands of photos and video clips of Buddy.

“We also get a lot of reported sightings, only one of which has been verified so far. Most of the time it’s a badger, a pig, a dog or a yellow-bellied marmot,” she says.

The one confirmed in-person sighting came from a hiker in the Fordyce Lake area near Donner Summit, she says.

Along with Shufelberger, Chris Stermer, senior environmental scientist with the California Department of Fish and Wildlife, has consistently tracked Buddy since his discovery.

“With our cameras we were able to estimate a home range of about 295 square miles, bordered by Highway 49 to the north, Interstate 80 to the south, 89 to the east and the Bowman Lake area to the west,” Stermer says.

Male wolverines typically make long treks to find a mate. So with no known females in the area, another question arose as the years went by: Why is Buddy still here?

“My hope is there’s a really camera-shy female here that made him stay, but there’s no genetics or pictures to support that,” Shufelberger says.

With no tracking, no mate and no major changes in behavior, Buddy started to seem like a dead end from a scientific point of view. But Stermer found a new use for the regular observations—using Buddy to figure out the best way to spot a wolverine, and transferring it to other places where there have been unconfirmed sightings.

Kevin and Kelsey from California Department of Fish and Wildlife mount a wildlife camera trap, photo

courtesy Faerthen Felix, UC Berkeley Sagehen Creek Field Station

Wolverines in California

By fine-tuning his camera system year after year, seeing how many shots of Buddy he got, and then calculating the probability of getting him in a picture with a given setup, Stermer was able to create a protocol that he figures nets him an 80 percent chance of spotting a wolverine if it exists in a given area.

Following up on numerous reports of a wolverine in the Hope Valley/Carson Pass region south of South Lake Tahoe, Stermer used the same protocol to place cameras with the best chances of spotting a wolverine.

“This past winter was the first winter I had 12 cameras in the Hope Valley/Carson Pass area, but I’ve been surveying there since 2014,” Stermer says. “It’s hard to be sure, but… I’d say there’s an 80 percent chance there aren’t wolverines in the area.”

California once was home to an estimated 50 to 100 wolverines—a species that doesn’t create dense populations and sticks to high, harsh, alpine climates, Stermer says, probably favoring the Southern Cascades around Shasta and the higher reaches of the Sierra Nevada.

Killed off in the early 1900s, largely by poisoned carrion as part of depredation efforts meant to protect livestock, wolverine populations were greatly diminished across the lower 48 states, Stermer says.

Now that researchers are gaining understanding of the importance of predators—watching the ecosystem-wide effects as wolves repopulate the West—work has begun to study the possibility of reintroducing wolverines to the Sierra Nevada.

And while such an effort is at least four or five years away, making it too late for Buddy, the lonely wolverine had a big hand in making it happen, Stermer says.

“Buddy has had a huge influence on reintroduction discussions. He sparked interest both in the public and in our department,” Stermer says. “Prior to Buddy, I didn’t hear much at all about wolverines.”

Buddy has also served as something of a test pilot.

“Sticking around for almost 10 years, he’s shown there’s still habitat there,” says Noah Greenwald, endangered species director for the Center for Biological Diversity.

Stermer says wolverines largely rely on carrion—large dead animals like deer, elk or moose—often digging up dead animals buried by avalanches under 10 or more feet of snow to sustain them through the winter.

Gun-cleaning bristles to catch fur for DNA and isotope analysis, photo courtesy Faerthen Felix, UC Berkeley Sagehen Creek Field Station

While Buddy has appeared healthy in all his photos, the fact that most deer in the area migrate to lower elevations in the winter means there may not be enough food in the Northern Sierra for more than one wolverine, Stermer says. Instead, the Central and Southern Sierra between Yosemite National Park and Sequoia National Park are the more likely candidates.

Likewise, female wolverines require a cold late-spring snowpack to den and have pups, Greenwald says, an increasingly rare resource in lower-elevation portions of the Sierra as climate continues to change.

A meeting on wolverine reintroduction across the lower 48 states is scheduled for July of this year, Stermer says, but studies are needed before wolverines could be reintroduced to the area.

Ensuring proper habitat, considering impacts on other endangered or threatened species, like the Sierra Nevada bighorn sheep and Sierra Nevada red fox, and potential interactions with people will all come into play, he says.

“The good news is they stay away from people. Through the eight-plus years [Buddy] has been here, there have been no negative reports of this wolverine interacting with people or pets,” Stermer says.

Politics will also come into play, as the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service is reconsidering listing the wolverine as endangered, Greenwald says, a decision his organization sued the department to achieve.

“We’ll see what the Trump administration does, but the science is clear that their habitat is at risk and there’s a small number of animals,” Greenwald says. “We’re definitely at risk of losing them in the lower 48.”

With all those challenges, why bother? Stermer says it’s a matter of making ecosystems healthier.

“What we’re really after in California is restoring that predator-prey relationship,” Stermer says. “When you try to bring back apex and smaller predators, it brings the whole system back into balance.”

As far as the likelihood of wolverines once again roaming the Sierra Nevada, Stermer remains optimistic.

“Public interest can really drive these types of efforts,” he says. “I do think there is a lot of talk about studying reintroduction.”

Greyson Howard is a Truckee-based writer. Find more of his work here.

Aaron Jensen

Posted at 00:20h, 20 AprilDriving on interstate 80 east bound in the Star Fire burn before Lakes Valley Road exit, a wolverine ran across the freeway. Three of us saw him. All of us are familiar with the wildlife in the area. He looked to be around 50 pounds, long reddish brown hair. Too big and fast for a marmot. Longer than a bear cub. Definitely didn’t run like a fox.

thomas gnauden

Posted at 21:03h, 17 AugustBack in the summer of 1989 I was camping at glacier lake up on Black Buttes in Tahoe National Forest. I had risen early before the sun came up, when the morning has that blue grey light, and on the other side of the lake (really a pond) there was a wolverine walking on the rock rubble at the base of the buttes. It’s a distinctive looking animal and I was surprised to see it. However, I had no idea they were rare. Being at 6000 feet elevation and roaming around before sunup I don’t imagine many people would see them.

Tahoe Quarterly

Posted at 07:52h, 18 AugustVery cool! Thanks for sharing, Thomas.