24 Jun Magnificent and Overlooked

In the grand natural arboretum of the Sierra Nevada, one of its hardiest and most underrated specimens stands as an enduring testament of time

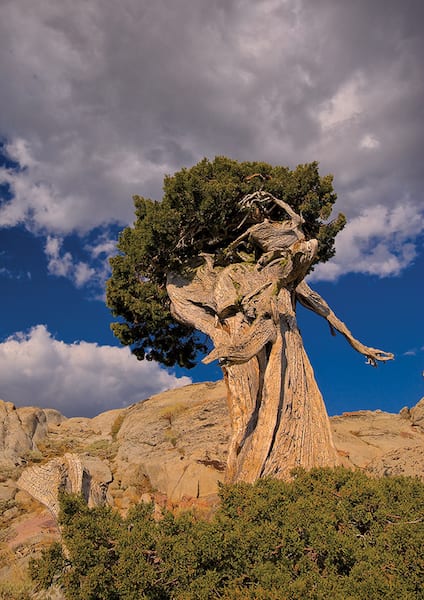

A twisted Sierra juniper on Carson Pass, photo by Tom Knudson

What I remember most about that hike near Carson Pass is not the tinseled sparkle of snowmelt streams or the icy dip in a mountain lake. It is what I found growing on a swale of granite that appeared to hold a thimble of soil: old-growth trees.

Stocky, sinewy and statuesque, those conifers were more than magnificent. They were works of art. Centuries of wind and snow had pruned and sculpted them into fantastic shapes and forms. Some twisted and turned like ballet dancers; others crept over rocks like boa constrictors. Even their bark was stunning. Cinnamon-brown, it clung to the trees in thick, ribbon-like strands that, in the stained glass light of late afternoon, almost seemed to glow.

Four hundred and thirty miles long and 70 or so miles wide, the Sierra Nevada has long been known for the diversity and grandeur of its trees. “I cannot pretend to account for the extreme magnificence of the Sierra forest,” Asa Gray, the distinguished nineteenth-century botanist, said in a lecture at Harvard in 1878. “Evidently, there is something wonderfully favorable to the development of trees, especially coniferous trees. And it is not easy to determine what it can be.”

A juniper near Cascade Falls above Emerald Bay, photo by Martin Gollery

But among the many species that grow in the range, the conifers I saw near Carson Pass—Sierra junipers—are often overlooked. They don’t tower over the forest canopy like giant sequoias and sugar pines. They’re old but not as old as giant sequoias or bristlecone pines—the world’s oldest tree—in the nearby White Mountains. Even John Muir, who raved about the wonder and beauty of the Sierra forest, said little about junipers. And what he did say wasn’t always complimentary: a singularly dull and taciturn tree… Silent, cold and rigid, like a column of ice.

Muir was right about many things, from the glacial origins of Yosemite Valley to the importance of protecting wild places. He was a conservation icon, a prophet and high priest of wild nature. But I believe he misjudged junipers.

To me, they’re wonderful trees, as worthy of praise as the stateliest sugar pine, the most regal sequoia. But it’s more than their gnarled and majestic presence I find impressive. It’s how they survive in places other trees would perish, not like monks walled off from the world, but as part of a wider ecological community. They get by with a little help from their friends.

A weathered juniper on Donner Peak has undoubtedly endured many storms over the centuries, photo by Bill Stevenson

You don’t have to go far to find Sierra junipers. They are scattered across the Sierra Nevada, mostly on the east side, including the Lake Tahoe region.

Some extraordinary junipers cling to the rocks around Donner Summit. This summer, I suggest you go have a look. “The Sierra junipers of Donner Summit are amazing,” says a publication of the Donner Summit Historical Society. “They have been sitting for millennia in the harshest conditions. They are our own bristlecone pines…”

Other places to find Sierra junipers (which are closely related to the more widely distributed western juniper) include Desolation Wilderness west of Emerald Bay, the Western States Trail as it climbs out of Squaw Valley and Sardine Peak north of Truckee.

Not long ago, my wife and I and two friends hiked through a grove of stunning Sierra junipers near Sardine Peak. There was one gnarled old tree after another. Two of us could not get our arms around the largest one; we estimated its circumference at 17 feet. I felt like a parishioner in a church. It was like walking through a temple of trees.

“There’s something about these handsome rock-dwelling relatives of cypress that give me pause at each and every encounter—I have never frowned on a juniper,” wrote Joe Medeiros, professor emeritus of biological sciences at Sierra College, about Sierra junipers in an essay in The Illuminated Landscape, A Sierra Nevada Anthology.

“We feel the grove’s energy—unexplainable but unmistakable,” Medeiros continued, describing his favorite stand of junipers high above the Lyell Fork of the Merced River in Yosemite. “It feels different sitting there than when in camp. Something calls us to stay here longer—and saddens us when we bid farewell. It’s more than simply a warming feeling; it’s an almost indescribable sensation of strength, truth, acceptance, welcome and understanding. It’s the palpable presence of wildness that I think Thoreau was trying to explain.”

The Bennett Juniper in the Stanislaus National Forest is believed to be the largest and oldest Sierra juniper, photo by Dave Bunnell / Under Earth Images

What’s believed to be the largest and oldest Sierra juniper grows in the Stanislaus National Forest: the Bennett Juniper. I’ve not seen it. But at 13 feet in diameter and more than 80 feet tall, it must be spectacular. “Even today, the Bennett Juniper sports a deep, luxuriant crown supported upon a full-barked, tapering trunk that is surmounted by only a negligible amount of dead wood,” wrote Ronald Lanner in Conifers of California.

Even more striking is the tree’s estimated age: 3,000 years. You read that right: three-thousand years, not 300. The Bennett tree was old when the Declaration of Independence was signed in 1776. It is older than the United Kingdom, older even than the Roman Empire.

Just imagine the weather old junipers have endured—the punishing snow, pummeling wind, arctic cold. The prolonged droughts of the Medieval Warm Period (950–1250 A.D.) didn’t faze them. Nor did the Little Ice Age (1300–1870 A.D.), which caused glaciers to advance across North America. As one of my hiking friends put it: “That was a mild winter to them.”

They’re hardy trees. Still, I worry about the future. Global warming is stirring change in the Sierra. As temperatures rise, cold-dependent species such as alpine chipmunks and bristlecone pines are expanding their ranges upward. But there is only so far they can go. It’s obvious Sierra junipers can withstand extremely harsh winters. What about warmer ones?

For now, they seem to be doing fine. That’s good news, not just for junipers but the mountain world around them.

Whether they cling like gargoyles to rocky eaves overlooking river valleys or grow in scattered clusters in middle-elevation forests, junipers are not as aloof and isolated as they appear. Spend time with them and you’ll see mountain bluebirds, Townsend’s solitaires and other birds land on their gray-green branches and feast on rich, bluish berries.

A juniper near Jackson Reservoir north of Truckee wears a fresh coat of snow, photo by Timothy Erskine

Those birds are not just bulking up on berries. They are doing the trees a favor by scattering the seeds in those berries in their droppings across the Sierra. They are planting junipers, some of which may live for a thousand years or more.

“The erratic distribution of western (Sierra) juniper in the Sierra, with individual trees sometimes a mile or more from the nearest seed source, emphasizes the role of birds and other animals in disseminating juniper seed,” wrote Stephen Arno in Discovering Sierra Trees. “Experiments have shown that much juniper seed will not germinate unless it has passed through the alimentary tract of some bird or mammal.”

That’s not all. Bluebirds, chipmunks, squirrels, deer mice and other creatures also weave the thick, ribbon-like bark of Sierra junipers into their nest linings. They need the trees. The trees need them.

A juniper on Carson Pass, photo by Tom Knudson

On the trails I frequent around Truckee and Lake Tahoe, Sierra junipers are tattered and battered, bent and twisted but sturdy and strong. For that, I’m grateful. With nature under siege on so many fronts, we need Sierra junipers and the wild places they inhabit more than ever. They are reservoirs of hope, antidotes to despair.

Tom Knudson is a Pulitzer Prize–winning journalist and former environmental reporter for the Sacramento Bee.

Heidi Perryman

Posted at 07:06h, 26 JuneThe sierra Juniper is a favorite site, gnarled or stately. I call it the “Tree of difficult things”.

https://customcollegeessays.com/blog/world-war-1-essay/

Posted at 03:34h, 13 AugustThese landscapes showed me how many amazing places on our planet are worth visiting to enjoy this splendor.

Inga Waite

Posted at 15:36h, 21 MarchImagine building an off -road mountain bike trail right through desolate wind swept family of these ancient sentinels. This is just what our National Forest Service has done at Lily Lake near Fallen Leaf Lake in the Tahoe basin. Portions of this newly minted Lily Lake Trail – which boasts “slick rock and boulder traverses” – go right over the exposed gnarled roots of stunted, ancient trees, clinging to those same boulders, trees that have survived for centuries if not millennia. Now the USFS is proposing adding electric bike access as well. Really? The comment period is still open, as of this writing, by visiting the Basin Wide Trail Analysis project on the fs.usda.gov web site. Leave your bikes and cars in the parking lot, take a walk, and feel the “palpable presence of wilderness” Medeiros describes, before it is sadly too late.