01 Jul Lost in a Rugged Land

An experienced Tahoe hiker goes missing deep in the Sierra backcountry, prompting a search and rescue while leaving loved ones anxiously awaiting his safe return

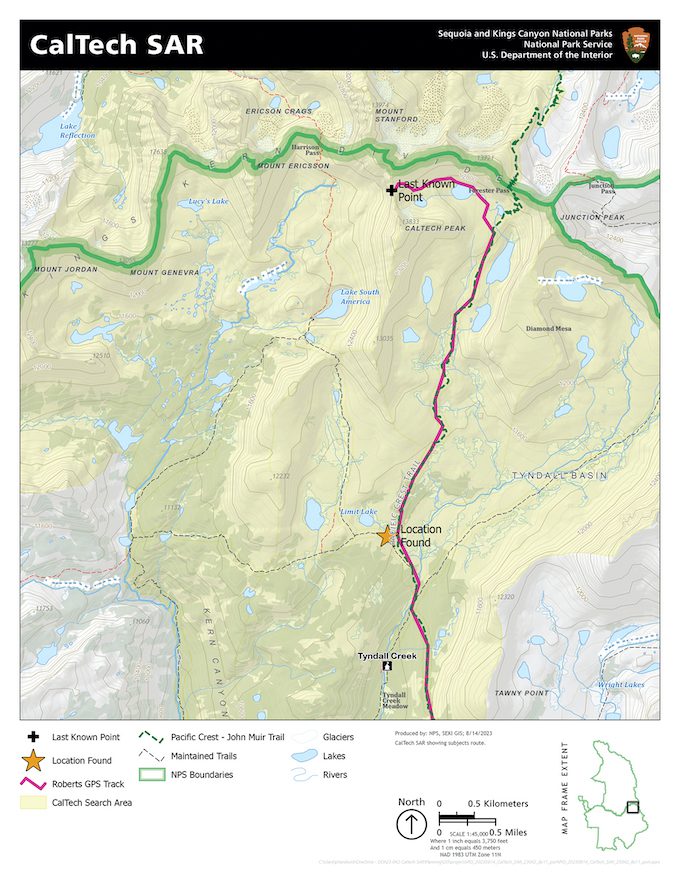

In August 2023, social media lit up with news that one of North Tahoe’s own, 76-year-old longtime local Bill Roberts, was lost in the rocky wilderness off the John Muir Trail. His Garmin GPS went dead near Forester Pass, the highest point on the trail at 13,153 feet, and he had not arrived at a designated meeting spot with his daughter.

Roberts’ wife Helen dropped him off at the trailhead in Cottonwood Canyon, south of Mount Whitney, on Tuesday, August 8. She took a picture of him smiling at the trailhead. Five days later that photo was emblazoned all over the Internet as the “please help find this guy” image.

Looking southwest from Kearsarge Pass. Bill Roberts’ daughter reported him missing after he did not arrive at their meeting point near Kearsarge Lake, where she was supposed to resupply him for his next leg to Muir Trail Ranch, photo by Sylas Wright

“We were camping at Kearsarge Lake, waiting for Dad to get there,” says Roberts’ daughter Meggie Inouye, who was to resupply her father for the next leg of his 20-day hike to Muir Trail Ranch. “We hiked in on Friday, August 11, and were supposed to meet him at the junction around noon on the 12th. I was running a bit late, but he wasn’t there.”

She asked all the northbound hikers if they’d seen him. Nobody had. But they told her conditions were challenging because of all the snow from the mega winter of 2023, which perhaps slowed Roberts down.

“I was getting pretty freaked out,” says Inouye. “My Dad had his tracker. We noticed on Friday before we got on the trail that he was on top of a ridge. He likes to do challenging stuff. I sent him a message: ‘What are you doing on top of the ridge?’”

There was no response.

Inouye ran into a wilderness park ranger, who radioed a front-country ranger. They contacted Roberts’ wife, who confirmed that the tracker hadn’t moved for 24 hours. The National Park Service then initiated a search while Inouye and her family returned to Kearsarge Lake to spend the night.

“It was awful. There was thunder and lightning all night long and we were worried,” says Inouye.

The next morning the ranger recommended they hike back out to Big Pine, the nearest town, to await word on the search.

“It was just anxiety-provoking the whole time. I was there with my kids and my husband, so I had to keep a level head,” says Inouye, who tried to console herself with the knowledge that her dad—who was embarking on his first solo backpacking trip—was an experienced mountain hiker. “He knows how to take care of himself well. He knows how to be in the woods. The JMT (John Muir Trail) is pretty mild. We have done a lot of big mountaineering trips. He has been hiking since I’ve been able to walk and has hiked around the world, including all the 14,000-foot peaks in California.”

Why, then, had he seemingly vanished from the trail?

Bill’s Adventure

Hiking north from Cottonwood Pass, Roberts reached the ascent up Forester Pass on his fourth day, August 11.

“All went smoothly until 9:30, when I lost the trail about a mile and 600 vertical feet from the pass,” says Roberts. “I traveled the snow-free rocky areas just west of the trail. Just ahead stood a rock face referred to as ‘The Wall.’ The cliff is normally climbed via switchbacked ledges, but these were blanketed by snow, so I made a direct ascent to the east side on snow, using my micro-spikes for grip.”

Due to the big 2023 winter, the John Muir Trail near Forester Pass was buried under sun-cupped snow, courtesy photo

Roberts followed the steep ridgeline, looking for a path across the wall, and located a rocky notch that he thought would do the trick. But when he arrived, he discovered a cliff on the other side, so he kept going, eventually locating another potential crossing, following a deer track that he would later learn was just north of Caltech Peak, at 13,500 feet.

The faint trail was walkable for about 50 feet, then turned into “barely manageable scree, which led to an unmanageable 12-foot vertical drop,” says Roberts, who worked his way around and climbed down the Class 4 rock. “While down-climbing, I placed my hiking poles on a ledge to free up my hands. Unfortunately, the poles fell about 20 feet into a crack.”

Realizing how important poles were in his situation, he gently dropped his pack off the rock ledge so he could retrieve them. But the pack landed on a slope and rolled down the chute about 400 yards, “shedding my water bottle and sleeping pad fairly close to the start of its rolling descent,” Roberts says.

Before heading down to pick up his pack, he went back to extricate the poles but “was unsuccessful in doing anything but pushing them back down into the slope below, from where they continued down the same path as the pack, and I never saw them again,” says Roberts.

It was about this time that it started to rain.

Surely wondering when his luck would improve, Roberts worked his way down over shaky talus and found his pack. But his Garmin was in a pocket that ripped apart as the pack somersaulted down the hill, and he couldn’t find it.

After donning his damaged pack, Roberts slid on scree and glissaded on snow down to about 12,400 feet, where he ate lunch and filled his water. He then worked his way back up to the ridge but discovered there was no easy way to get back to the trail.

It was now windy and raining hard, so he backtracked to the bottom of the bowl and pitched his tent for the night.

“The wind and rain continued until about midnight. I spent some wakeful hours with some self-incrimination, map study and, finally, prayer,” says Roberts. “My prayers gave me no answers but renewed my confidence that God would be with me, whatever the next day brought. I knew very well that I was lucky to have found my pack. I was dry and warm and fed and was finally able to sleep for a couple of hours.”

Lost and Confused

The next morning, August 12, dawned warm and dry, and Roberts contemplated his next step.

“I trusted that I would be found or would find my way out, but I was painfully conscious of all the suffering and worry that I would be causing my family and my friends as soon as I was known to be missing,” he says. “My focus over the next two days was to find a way to let them know that I was OK as quickly as possible.”

The view from a search-and-rescue helicopter shows the location where Bill Roberts lost his GPS near Forester Pass, courtesy photo

The tricky part about being lost, however, is that while Roberts knew he had lost his way, he still felt he knew where he was, only to find out several times over the next few days that he actually did not.

Reviewing maps and looking at the terrain, he saw the nearest labeled northbound trail was 3 miles cross-country to his west. By 1:30 that afternoon he had made his way to a trail junction sign indicating the JMT was just 2.4 miles away. He followed the path before realizing it was heading directly south, when he believed he wanted to be heading north. He hiked for over two hours from the signpost before encountering a swift, waist-deep stream—treacherous in any conditions, but even more so with his poles lost somewhere near Forester Pass.

He traveled upstream looking for an easier crossing, but with 20-foot cliffs, all options looked dangerous. So he turned around and returned to the same JMT post he reached hours earlier.

At that point, says Roberts, “I revised my goal of traveling north to rejoin the JMT to get back to the JMT anywhere.” He hiked uphill from the signpost for about 20 minutes, lost it in a swampy area, then resumed climbing off trail. After regaining the path, he decided to hunker down to spend a second night lost in the wilderness.

“I ate a good meal and slept pretty well that night, knowing that I had a trail to follow the next morning,” says Roberts.

About 10 p.m., a thunderstorm hit, pounding his tent with soaking rain until early in the morning.

‘SOS’

Roberts emerged from his tent to bright sunshine, a new day and new hope. He followed a trail to the top of the ridge, then lost it.

“At that point I was so confused by the signs and the terrain that I thought it best to stay in place and wait for help,” Roberts says.

He made his way to a large open area, wrote “SOS” in the sand and waited. A search-and-rescue helicopter passed by in the distance.

“On its return trip, it traveled directly over me,” says Roberts. “I waved the tent fly and my arms—I was wearing a red poncho—but was disappointed to see it continue west.”

He figured if a helicopter could fly overhead and miss him, he needed to find a way out himself. So he set out again, scampering up steep terrain and stark granite and snow up to 12,800 feet before getting discouraged again and returning to the spot where he signaled the helicopter. After waiting an hour, the helicopter made another pass, and he made yet another valiant attempt to signal it, without success.

Roberts then headed down into a valley, where he encountered the same sign he’d seen 20 hours earlier. He realized he had hiked a complete counterclockwise circle over challenging and exhausting terrain.

To add insult to injury, it began raining again, so Roberts tucked himself into the tent for another night.

Luck at Last

In the morning Roberts was able to successfully follow a trail for a mile to the south before climbing on sketchy terrain around South America Lake.

It was then that his luck finally improved in a big way: He spotted fresh footprints. At 11:30, he looked up to see two women on the trail.

A map illustrates where Roberts was eventually found, only a 10-minute walk from the trail, courtesy photo

“I frantically waved and shouted,” says Roberts. “I briefly told my story and the tears came up as I told them how desperately I needed to talk to my family. Renee and Jeannie were the very best people I could have encountered. Renee had an inReach (Garmin device), so she messaged Helen and Meggie and the SAR. Jeannie fed me while they both reassured me that everything I did made perfect sense and was totally understandable.”

They found him about 5 miles south of Forester Pass, just a 10-minute walk from the John Muir Trail.

Roberts, who was in good condition, “just very tired,” says it wasn’t until he debriefed with the rescue team after his helicopter flight to Bishop that he regained his bearings and realized where he had been.

“I was still under the false notion that I had traveled over the Kings/Kern divide and was in the basin northwest of Forester,” he says. “Because of that, I gave them a lot of incorrect information. I spent many hours over about two weeks reviewing maps and Google Earth photos with Chris (Inouye’s husband) and finally determined that I had gone over Caltech Pass into the basin just north of South America Lake.”

Home Front

Undeterred, Bill Roberts returned to the John Muir Trail just 10 days later to complete the northern section of the trail with friends Jackie and Bernard Clark, courtesy photo

Helen Roberts admits that when her husband’s tracker stopped sending messages, and he failed to reach the meeting point at Kearsarge Lake, she was genuinely concerned for his safety.

“I’m generally a worry-about-it-when-it-happens person, but this one was tough,” she says. “It was a lot of waiting, worrying and hoping.”

When she got the call from the two women who found Roberts, “It was emotional and very, very relieving,” says Helen. “He was talking about continuing to hike, and the rescue people and Meggie said, ‘You shouldn’t do it.’ While he didn’t want to helicopter out because of the cost, Meggie said, ‘You are getting on a helicopter!’

“There have been a lot of people that said I should be so angry with him. But that is who he is,” Helen adds. “I would never stop him from going out.”

Ten days later, Roberts returned to hike the northern quarter of the JMT—this time with a couple of friends.

An avid backpacker himself, Tim Hauserman was impressed with the sense of calm that his friend Bill Roberts displayed during his wanderings amid the steep, confusing configuration of talus and sun-cupped snow in the High Sierra.

David Roberts

Posted at 06:27h, 25 JulyI’m Bill’s brother_ it’s hard to not get emotional reading this account-this was a serious situation, the “Wall” on his east kept gradually curving till he was hiking west not north- ending up iat CAltech peak- the helicopter picture of CalTech peak shows unbelievable terrain my brother had to navigate. Thankk god he made it. Great article– Dave Roberts