24 Sep Mental Matters

The benefits of training the mind extend beyond professional sports and into the recreational arena of skiing

“To achieve maximum send, you must first find maximum Zen.” This sage advice came from a skier no older than 12, on a chairlift at Squaw Valley. He was being coached by a friend of mine, and I had joined their team on the lift.

I chuckled, then reflected on the depth of that nice little rhyme. Being more than 20 years older than this fellow, I was intrigued by the connection he made between executing something difficult and getting one’s mind in the right place. He seemed an astute disciple of the art of mental training.

Mental training falls into the field of sport psychology, which is defined in the book Foundations of Sport and Exercise Psychology as “The scientific study of people and their behaviors in sport and exercise contexts and the practical application of that knowledge.”

Elisa Chapman, a certified mental performance consultant and founder of The Mobilized Mind in Tahoe City, believes that mental training for athletes basically ties into the second half of that definition: the practical application of that knowledge.

Truckee skier Daron Rahlves, center, and Jérémie Heitz prepare for the Race the Face, an unprecedented giant slalom on the 50-degree Hohberghorn face near Zermatt, Switzerland. Rahlves, a former alpine racer and Olympian, used mental training throughout his career and still does to this day, photo by Mika Merikanto, courtesy Red Bull Content Pool

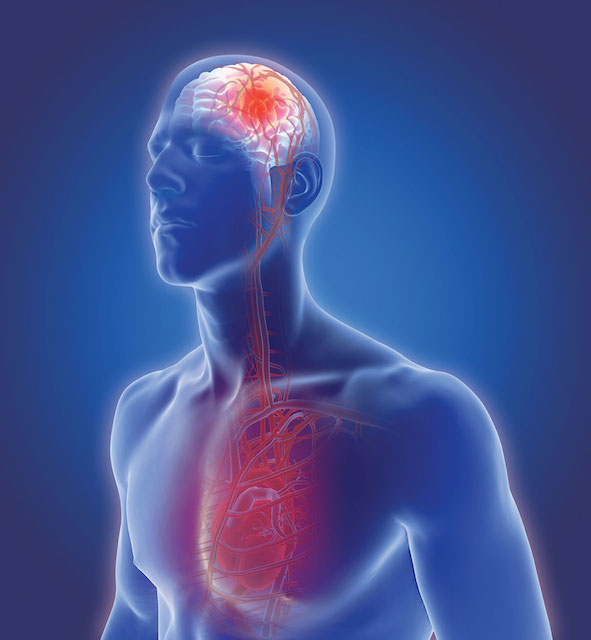

While not all snow-lovers are out to achieve “maximum send” in the sense of taking big, sketchy airs, who doesn’t want to perform optimally? With another ski season around the corner, many will look to the gym or buying new gear as a main path to prepare. Both can be beneficial, but another piece of the puzzle is dedicating specific time and energy to the 3-pound lump of gray matter between your ears. Yes, the brain! The reams of scientific literature support the power of tapping into the mind as a training tool.

Some of the most common, and tangible, examples of mental training practiced by professionals include positive self-talk, mental imagery, breathing, focus and goal-setting, although there are many more.

While training these skills has traditionally been reserved for high-level competitive athletes, or sports like golf, baseball and ski racing, it is shifting into a wider realm of sports, and even into the recreational arena. In other words, it has the potential to benefit everyone who wants to improve.

“Mental training can help everyone, and it has a place for all. It helps relax you, fires you up and gets the most out of what you want to accomplish,” says Daron Rahlves, a Truckee resident and retired alpine ski racer with a dozen World Cup victories and three Olympics to his name. Although his racing career ended in 2006, he still applies the lessons from his formal mental training years to the slopes today.

“To this day I use affirmation and cue words, a positive mindset and positive mental imagery in all physical efforts. It helps in many situations,” Rahlves says.

A Little Help from the Brain

But, some will ask, “Why bother? Can’t I just go skiing and have fun? I seem to be doing just fine.”

Fair enough, but perhaps there is a happy place where the practice of mental training sits in the Venn diagram for skiers who want to be a bit better, and methods that won’t require hours on end each day. And while the mind undoubtedly is an important tool for optimal performance, few have a routine to train it specifically.

©istock.com/LarsNeumann

“As humans, there are only three things that we can train: our craft, our body and our mind,” says Dr. Michael Gervais on his performance psychology podcast Finding Mastery. “We spend ridiculous amounts of time training our craft and our body.”

When it comes to skiing and snowboarding, most people’s brains could use a little help. Who hasn’t felt the range from nervous to downright terrified at the top of a challenging run? And, who wouldn’t like to be able to manage these thoughts and emotions to achieve a desired outcome?

“There’s no doubt that skiing is very psychological,” says Dr. Jim Taylor, who has worked with many Olympic and professional athletes as an internationally known authority on sport psychology. “Whether it’s KT-22 or wherever, confidence is an issue, fear is an issue, the ability to focus is an issue. So, certainly there are a lot of mental tools that recreational skiers can use to ski better.”

Dylan Tomlin, head coach at the Auburn Ski Club on Donner Summit—which trains 200 athletes of various levels, from weekend casuals to Olympic hopefuls—has seen his athletes benefit significantly from mind training and believes that mental work is applicable to a more mainstream crowd as well.

“The mental side of training is valuable for everyone. Competitive kids may notice the benefits sooner. But the benefits themselves are the same on the recreational side,” says Tomlin.

However, the training is work, requiring structure, focus and practice. An introductory time commitment may be similar to that of meditation, around 10 to 20 minutes.

“To start, 10 minutes of a day is a significant investment in mental training,” says Gervais on his podcast.

Consider how this stacks up against the standard 40-plus-hour work week, plus five hours or so per week in the gym. Again, like the gym, you get out what you put in.

“Everyone’s going to follow it [mental training] on a different point on the spectrum,” Chapman says. “Just like professional athletes, some don’t do it at all, and some do it a ton, and some have one foot in the door. So, the same thing is likely to happen at a recreational level.”

A Modernized Approach

The concept of mental training may become more familiar when the label is removed. Most were exposed to it in youth sports, although likely in a rougher form—a coach, perhaps in a loud, aggressive and somewhat frightening voice, yelling, “Focus!” or, “Get your head in the game!” While it may have been well-intentioned advice, such instruction falls quite short on specifics.

Yani Dickens, sport psychologist and director of training at the University of Nevada, Reno, explains how certain well-intentioned phrases from coaches and peers can backfire. For example, telling athletes “not to worry about it.”

“The problem is that, by telling someone not to worry, you’ve identified that worrying is a problem, which isn’t always the case. And, it reminds the athlete that trying to ‘not worry about it’ hasn’t worked so far, so why’s it going to work now, when a coach tells me?” Dickens says. “They need more than that.”

Therefore, perhaps the upcoming ski season is an opportunity to take the mental game a few notches past memories of an angry soccer coach screaming with something of a hardened terror in his or her eyes, and toward something a little more elevated.

“As a competitive athlete, you’re told to focus, you’re told to be confident, you’re told to use visualization—you’re told a number of these things. But there’s a disconnect,” Chapman says. “There’s the ‘how’ piece. I think what I have, in my work, is the opportunity to expose my kids to how they can actually do these things that everyone’s telling them to do.”

The Power of Imagery

“Imagery is the most powerful mental tool there is,” says Taylor, who, as an aspiring teen, turned an unspectacular ski racing career into making the U.S. Ski Team after he was introduced to a structured imagery practice.

Mental imagery, like it sounds, involves athletes imagining themselves performing a specific activity, using all of their senses, with great detail. It goes far beyond that, however, and there are a few steps and techniques to get the most out of it.

Tahoe native and Olympian Bryce Bennett envisions a training run, photo by Max Hall, courtesy U.S. Ski Team

The idea is to mindfully and methodically run through the act of an intended performance over and over again in the mind. Rahlves used imagery throughout his career, after first working with a U.S. Ski Team sports psychologist at the age of 23.

“Positive mental imagery has helped me learn new skills and get me hyper-focused,” he says. “My advice would be to try a few different routines, write down what you did and how it helped or not… You will notice the benefit in how much more confident you are in yourself.”

The power lies in the real benefits of the imagined act.

“There’s a ton of research that you can actually get better technically by just doing imagery,” Taylor says. “The mind and the body don’t know the difference between an imagined run of skiing and an actual run of skiing. There’s great research that shows that when you imagine yourself skiing it actually triggers your muscles and triggers your motor programs.”

Plus, it’s not an enormous time commitment. Taking 10 minutes off the morning Instagram/phone habit will free up more than enough time. Taylor recommends about five minutes a day, three to four days a week. Gervais recommends six to eight minutes per session.

For elite athletes, the imagery goal might be based around doing something never done before, like an Olympic world record. But it need not be anything so daunting for the recreational athlete. The goal might be skiing a new steep zone, landing a small cliff or basic trick, or just arching a smooth turn on some cleanly cut corduroy. If a few minutes a day can translate to even a tiny improvement, it could be worth considering.

The Mental Aspect of Breathing

Chapman has a fundamentals training program she uses with clients—comprised of breathing, imagery and self-talk—but she starts with breathing. “Because it’s with you all the time, you can’t forget it,” she says. “You can’t leave it at home by mistake.”

But what does breathing have to do with the mind? In fact, the two are intricately intertwined.

“Breathing, while a physical act, falls into the category of a tool that can help produce a more optimal mental state,” says Chapman.

Slowing down the breath overall, having targets for the length of each inhale and exhale, and breathing through the nose are some tangible examples of what it means to “work on breathing.” Research shows this can reduce anxiety, increase relaxation and more.

Rapid inhales can rev us up and turn on our stress systems, as the inhale acts on our sympathetic nervous system. Conversely, long exhales can help us slow down our heartrate and relax, as the exhale acts on our parasympathetic nervous system (both the sympathetic and parasympathetic systems are part of the autonomic nervous system, which regulates a variety of body processes that can take place without conscious effort).

Getting revved up and calming down can be beneficial at different times, but to return to skiing, a sport rife with challenge and danger, relaxation is likely the direction most people want to go more of the time. This can have applications in standing atop a chute that is icier than anticipated, or simply trying to find a parking spot on a pow day at 9:30 a.m.

Chapman recommends a target of six breaths per minute, 10 seconds per cycle, with four seconds on the inhale, and six on the exhale. This timeframe and ratio is not a cookie-cutter fit for everyone, as different recommendations on times have been made by experts, and thus personal tweaks may be needed.

There are uber-simple apps (Kardia is one example) that allow users to program the intended inhale/exhale and total time for the session, and thus provide a straightforward avenue to get started.

“By practicing at home, you learn how to create balance in your nervous system,” Chapman says. “You can control how you breath and it’s about focusing on what you can control.”

While improved skiing might be the specific desired outcome, the benefits of mental training extend into the overall well-being and health of an individual as well. Plus, the more training we log, the sharper our mental tools will be on that sweet, sweet day when the lifts spin, in all their glory.

Tahoe City-based writer Dave Zook has become fascinated with the mental side of sports and performance via firsthand experience getting nice and terrified on the slopes, listening to podcasts, and reading books and articles. He hopes to continue the learning process throughout all of life.

LEARN MORE

• The Outside Podcast: Interview with Dr. Michael Gervais (step-by-step imagery discussion starts at 18:30)

• Tedx Talks: The Secret Imagination of Elite Performers/Charlie Unwin (available on YouTube)

• Tedx Talks: Breath to Heal/Max Storm (available on YouTube)

• Breath: The New Science of a Lost Art: 2020 Book by James Nestor

• Dr. Jim Taylor: Website, www.drjimtaylor.com

No Comments