28 Dec The Forgotten Miracle

It was Saturday, February 27, 1960—the second to last day of the Squaw Valley Winter Olympics—and the recently built Blyth Arena was packed to the rafters.

The seething throng of spectators were gathered to watch the U.S. hockey team vie with the heavily vaunted squad from the Soviet Union for the right to play in the gold medal game. California Governor Pat Brown, along with about 10,000 others, was part of the standing-room-only crowd.

Against the backdrop of the Cold War, the Americans got off to a rough start.

“We took some penalties in the first [period],” says U.S. goalkeeper Jack McCartan. “And they got out to a 2-0 lead.”

The Soviets were heavy favorites, but the Americans scratched out a goal in the beginning of the second period.

“I personally felt the Russians were the team to fear, based on what they did in 1956,” says John Mayasich, a center with the 1960 U.S. team. “They won the gold medal in ’56 and they only got better.”

Mayasich was on the 1956 U.S. Olympic hockey team, which lost to the Russians in the gold medal game in Cortina d’Ampezzo, Italy. The smart from the 4-0 defeat lingered.

“Listen, the Russians trained 11 months out of the year,” says McCartan. “We’d never beat them before. If I told you I knew we were going to beat the Russians that day, I’d be lying.”

Veterans littered the Soviet roster—the oldest player, Nikolay Soogubov, was 35 and a World War II soldier. Several of the players were seasoned by a healthy slate of international play.

“I wouldn’t have bet my house that we would beat them,” says U.S. coach Jack Riley.

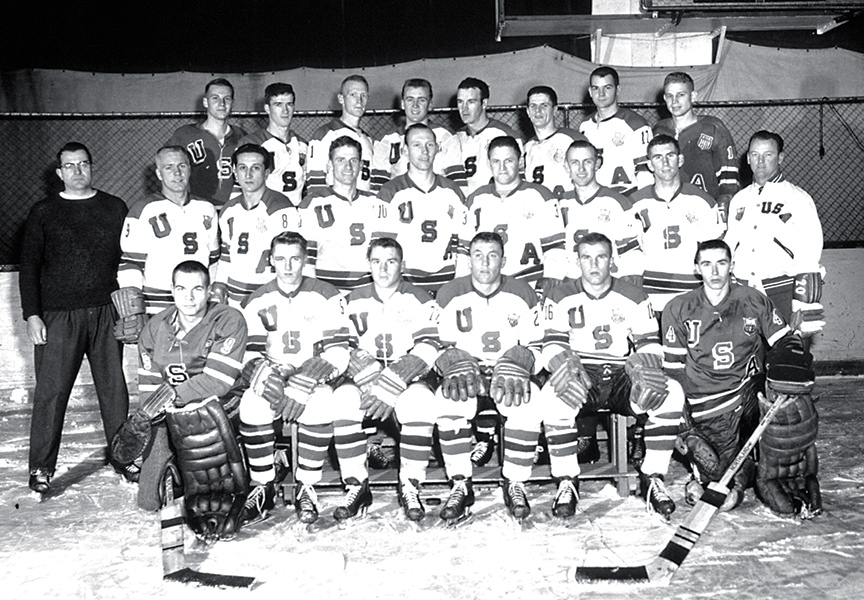

The 1960 U.S. Olympic hockey team, photo courtesy U.S. Hockey

By contrast, the Americans were a rag-tag crew of amateurs and college seniors. Center Tom Williams was only 19. They hadn’t coalesced after a year of grueling practices. Far from it. Two of their leading scorers didn’t even start skating with the other players until ten days before the torch was lit and the first puck was dropped.

But the one thing they had on their side was the crowd.

“That crowd was wild,” Mayasich recalls. “We were playing well against them and we started to just feel we had a chance.”

About 11 minutes into the second period, Bill Christian received a puck from his brother Roger in the offensive zone and took advantage of the Russian goaltender Nikolai Puchkov’s uncharacteristic mistake, punching the tying goal in the net and sending the crowd into a frenzy.

After Bill Christian’s equalizer, the teams battled furiously back and forth with the teeming fans increasingly on tenterhooks as time waned.

With five minutes left in the game, the United States inched closer to a miracle.

Tommy Williams navigated the puck to Roger Christian, who took a searing attempt on goal that was blocked by Puchkov. The ricochet found Roger’s brother Bill in front of the net.

Bill Christian delivered, catapulting the Americans into the lead.

The boisterous crowd surged as the Americans held the USSR in check for the final minutes, securing the most improbable victory in the history of the U.S. hockey program and sending the team to the gold medal game.

It was the first time the United States had ever beaten Russia in hockey, but it would not be the last.

A Cross-Section of Miracles

Some sports enthusiasts of a certain age remember exactly where they were on February 22, 1980, when Al Michaels, the iconic sports broadcaster, cried out: “Morrow, up to Silk. Five seconds left in the game. Do you believe in miracles?! YES!”

“The miracle [in 1980] transcends hockey,” says Dave Fischer, a communications director for USA Hockey. “It was just a time in our country where there was so much going on.”

Akin to the 1960 Olympics Games, the political connotations of international sporting events—especially the tilts between the Soviets and the U.S.—were fraught with ponderous freights of national pride exerting considerable pressure on the coaches and athletes representing the dignity of their country.

It’s perhaps why the 1980 semifinal match, when the U.S. beat the Soviets, is often cited as the greatest moment in twentieth century athletics.

Yet, the 1980 team had a considerably easier road to gold medal glory than the 1960 national team.

“The ’80 team never beat Canada, they didn’t even play them, and they tied Sweden,” says Riley. “We beat everybody.”

The difference in media landscapes renders the latter-day miracle so salient in the minds of the greater public, while the earlier run toward goal recedes toward the fringes of athletic lore, Fischer says. In 1960, most of the Olympic hockey games were not televised. While those in attendance likely never forgot the intensity of the contests, and the players retain a staggering level of recall clarity, they are the sole witnesses.

The gold medal ceremony was barely attended by any members of the public, Riley says. After the Games, the team disbanded without pomp, the players returning to their studies at various universities or their 9-to-5 jobs.

No endorsement contracts, no ascension to the professional ranks with the concomitant financial security. The players vanished back into the obscurity of normalcy, void of the clamor, the acclaim and the adulation that greets today’s successful athletes, who vie for victory and fame in a world of media saturation.

Assembling the 1960 Team

Another difference between the two miracles is that the 1980 incarnation boiled down to a single game, with the Americans beating a Soviet team that was widely accepted as significantly superior.

In 1960, the U.S. squad was considered to be the fourth-best team in the tournament.

Czechoslovakia, Canada and the Soviet Union were all rated better, with many pundits actually dubbing Canada, not Russia, as the favorite to top the podium.

“Very few teams beat Canada or the Russians,” Riley says. “I never really thought we would beat them.”

The fact that Riley made a controversial decision just a few weeks before the commencement of the tournament didn’t foster optimism regarding the Americans’ chances.

At the end of January 1960, Riley informed his team he would be adding the Cleary brothers from Boston to the squad.

Bill Cleary was a Harvard man, and scored copious goals for the collegiate team in his brilliant career. So, there wasn’t much protest in adding a prolific scorer to the team, Riley says.

But it riled many that Bill laid down an ultimatum: He wouldn’t come unless his brother was allowed to join.

“Bill didn’t want to take time off his insurance business unless his brother Bob could go,” says goalie Jack McCartan. “It must have been about ten days before the tournament.”

McCartan and others in the locker room took exception to the eleventh hour move, some even hinting at a mutiny against Riley.

“We knew Bob could score,” McCartan says. “But we had guys that were playing with the team for the last year that just got let go. That was a topic of concern.”

In a staggering twist of fate, the last hockey player cut from the 1960 team was Herb Brooks, who would go on to coach the 1980 team and inspire a miracle of his own.

“(Brooks) was a good hockey player,” McCartan says. “But he was a better coach.”

Another late but less controversial move was the addition of Mayasich, widely considered to be the best hockey player in the United States at the time.

Mayasich was a center forward in college, but he switched when he realized he could get more time on the ice as a defenseman.

“He was the premier guy in the U.S.,” McCartan says. “He was one of those natural players and his skills were really unbelievable.”

John Mariucci, who coached Mayasich at the University of Minnesota, once said: “John brought college hockey to a new plateau. He was the Wayne Gretzky of his time. And today, if he were playing pro hockey, he would simply be a bigger, stronger, back-checking Gretzky.”

While Mayasich, who was instrumental in developing the slapshot, a move he tinkered with while in college, was welcomed by the team, the addition of the Cleary brothers still rankled some members in the days and hours leading up to the first face-off.

In the end, cooler heads prevailed after the players saw the Cleary brothers in action. Bill Cleary went on to lead the team in points for the tournament, garnering seven goals and seven assists.

The Tournament

The Americans sailed through the first round, beating Czechoslovakia 7-5 and routing Australia easily by a score of 12-1.

The schedule was relentless.

“We only had one day off the whole tournament,” Mayasich recalls.

The first round led into the medal round, where the U.S. calmly dispatched Sweden 6–3 to set up a highly anticipated match with the Canadians.

The Canadians were led by Bobby Rousseau, who would go onto a superlative hockey career, scoring 245 NHL goals and winning four Stanley Cups as a member of the Montreal Canadiens.

With the game underway, Bill Cleary proved his mettle by notching the first goal. But the next goal was a shock.

“Everybody came to me before the game and said, ‘don’t play [Paul] Johnson, the guy is the worst defensive player in the country’,” Riley says. “Well, before the game I say, ‘What the hell, I’m gonna play him.’”

In the second period, with the Americans cleaving to a one-goal lead, Johnson intercepted a pass at center ice and began skating toward the Canadian goal. He got to the blue line and launched a shot that miraculously beat the goalie for a 2-0 lead.

“I asked him what the hell we was doing and he said, ‘I saw an opening and I knew I could put it in,’” Riley says. “It was a helluva shot. It’s the shot that won the game.”

Indeed, Johnson’s extraordinary goal proved the difference as the Americans triumphed over Canada by a final score of 2-1. But McCartan, the goalie, was hailed as the true hero of the game after compiling 38 saves, 20 in the second period alone, causing some of his teammates to wonder if he used radar to block shots.

“He was unbelievable,” Riley says.

“McCartan was special that day,” Mayasich agrees.

For his part, McCartan is borderline dismissive of his contributions. “Hey, I made a few saves, and a few of their shots hit the post,” he says casually.

When pressed, McCartan admits he entered some kind of zone that athletes talk about, a kinetic feeling of anticipation that overtakes a contender for a few brief moments over the course of a career. “Yeah, it was one of the best games I ever played,” McCartan says. “But you don’t do that by yourself; I had a lot of guys blocking shots.”

McCartan, who was on loan from the U.S. Army for the tournament, was named Best Goalkeeper by the Olympic committee and is credited by many of the players and Coach Riley as the biggest factor in achieving the 1960 miracle.

American Gold

Squaw Valley, CA, Feb. 25, 1960—Pandemonium reigns as the members of the U.S. hockey team scramble on the ice for the puck a moment after they beat the highly favored Canada team 2-1 in the Winter Olympics. Right in the middle of the pile, his skateless feet in contrast to those of his players, is the American coach, Jack Riley, photo courtesy USA Hockey

After upsetting the Canadians and then beating the Russians in subsequent days, the Americans beat a solid Czechoslovakian team in the gold medal game to emerge from the grueling tournament as unequivocal champions.

Down 4-3 after two periods, the Americans rode Roger Christian, who scored a hat trick in the final period, and Bill Cleary to a 9-4 win, putting a punctuation mark on one of the greatest underdog runs in American athletics.

“It just worked out right for us,” Riley says. “I mean, we were lucky and we had a great goalie and that’s what you need. Everything worked.”

McCartan says his superlative performance highlights an athletic career laden with success—his team won the 1956 NCAA baseball championship with McCartan manning third base and hitting .349.

“It was the biggest thrill because it was so unexpected,” Mayasich says. “It’s just unforgettable.”

Meanwhile, Herb Brooks, back in Minnesota after being cut just days before the puck was dropped at center ice, watched his erstwhile teammates put the finishing touches on their magical run.

Brooks died in a single-car accident near Forest Lake, Minnesota, on August 11, 2003. There’s no telling whether being cut motivated the rest of his sterling career, or if his omission from the 1960 team had any bearing on American hockey’s second and more famous miracle.

But now a matter of legend, when the final seconds were ticking with the U.S. up 9-4 on Czechoslovakia, Herb Brooks’ father looked at his son and said: “It looks like the coach made the right decision.”

Matthew Renda is a Santa Cruz–based writer.

No Comments