01 Dec Tahoe’s Olympic Hat in the Ring

The pros and cons of a future Reno–Tahoe Winter Games

It’s a local myth that Tahoe’s development boom of the 1960s and ’70s—which radically reshaped the area landscape, endangered The Lake’s clarity and led to the creation of the Tahoe Regional Planning Agency—was due to the 1960 Winter Olympics at Squaw Valley.

Of course, some building can be traced to the Games. There was a mini boom in North Shore hotel accommodations and Squaw transformed from an undeveloped ski resort with one chairlift and two rope pulls into a modern facility capable of holding the greatest international sporting event on earth.

But, according to David Antonucci, author of Snowball’s Chance, the thoroughly researched account of how Squaw Valley founder Alex Cushing attracted the Games to a remote valley in the Northern Sierra, Tahoe’s enormous growth in the 1960s and ’70s was more attributable to the post-war boom in the economy rather than the Olympics putting Tahoe “on the map.”

What the Squaw Olympics did do was catalyze the western ski industry; locally, resorts like Squaw, Sugar Bowl and Heavenly expanded, while most of the other area resorts currently in operation opened not long after the Games.

Thanks to the 1960 Olympic influence, Tahoe is now a winter sports mecca. But is it one that should be shared with the world in future Games?

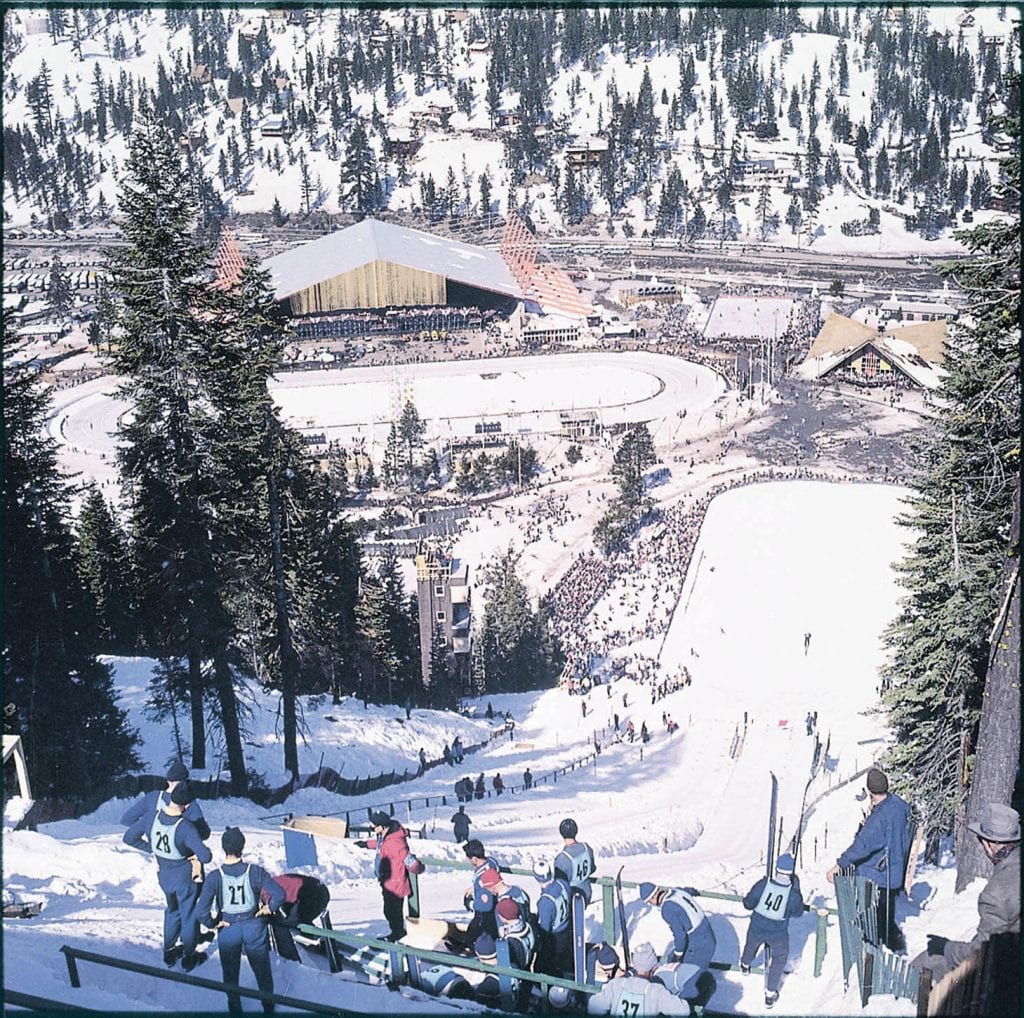

The ski jumping hill at the Squaw Valley Winter Games overlooked Blyth Arena and the speed skating venue, photo by Bill Briner, courtesy Squaw Valley

The ski jumping hill at the Squaw Valley Winter Games overlooked Blyth Arena and the speed skating venue, photo by Bill Briner, courtesy Squaw Valley

Possible Return to Tahoe

In September, United States Olympic Committee (USOC) officials expressed interest in bringing a Winter Games back to the country, specifically mentioning the Reno–Tahoe area along with Salt Lake City and Denver.

“We are definitely interested in hosting the Winter Games in the United States at some point and time,” says USOC chairman Larry Probst. “Our board needs to meet and talk about whether that’s 2026 or whether that’s 2030.”

However, area stakeholders, including the region’s business representatives, ski industry magnates, environmentalists and Olympic athletes, express a deep ambiguity over whether Tahoe is an appropriate candidate as a host city.

“I can say from our company’s perspective, our primary interest in hosting a Winter Games would be an opportunity to enhance transportation infrastructure,” says Andy Wirth, president and CEO of Squaw Valley Ski Holdings. “It has little to do with publicity.”

Wirth’s comments are echoed by many Tahoe officials, who assert that if the Olympics were to draw large public and private investment capable of transforming aspects of Tahoe’s infrastructure, it may be a worthwhile enterprise.

“If the Olympics brought a train from San Francisco to Squaw Valley and other lines from Reno to Truckee, I would be for it,” says Jeremy Jones, a professional big-mountain snowboarder and Truckee resident. “But it would have to futurize our transportation network. If it’s just additional highway lanes, I would be against it.”

Others fret that the influx of crowds and traffic would adversely impact The Lake.

“We love the Olympics and we honor our Olympic heritage here at Tahoe, but there is a big disconnect between the prospects of again hosting the Winter Games and the reality of life in Tahoe,” says Tom Mooers, executive director of the conservation group Sierra Watch.

Mooers doesn’t believe something like a light rail system would truly solve transportation problems in the Tahoe Basin.

“I think this idea that we can build our way out of the problems we have here is wishful thinking,” he says. “Look, Sochi saw $50 billion in investment and what does it have to show for it? Massive environmental degradation and a ghost town.”

Several environmental organizations expressed concern about the potential impacts the Olympics—and additional people, cars and emissions—could cause The Lake. While the 1960 Squaw Valley Olympics hosted 665 athletes, recent Winter Games have witnessed four times as many.

Those Olympics saw fierce construction, much of it not conducted in an environmentally sensitive manner.

“They did some things that by today’s standards would not be acceptable,” Antonucci says, noting that construction diverted Squaw Creek, which used to flow through what is now Squaw’s parking lot. Likewise, cross-country ski trails were cut through forests on the West Shore and left to languish, causing persistent erosion problems.

While updated environmental regulations in the Tahoe Basin would likely prevent similar mistakes, any Olympic commitment would entail significant construction projects, like building a ski jump, bobsled and luge runs, and necessary infrastructure.

South Lake Tahoe Chamber of Commerce CEO Steve Teshara says public and private investment in the region is an enticing prospect. But, he says, “Any investment connected with the Olympics might bring as many challenges as benefits.”

Some proponents of the Olympics point that the event might prompt many of the owners of some of the more derelict commercial properties, both on the North Shore and South Shore, to concentrate on reinvestment or even sell to developers willing to undertake it themselves.

But Teshara says that is already happening on the South Shore.

“We are enjoying revitalization and a fair amount of investment right now,” Teshara says, pointing to refurbishment projects at the Knights Inn, Bijou Marketplace and the new Lodge at Edgewood Tahoe, among others.

There is activity on the North Shore as well, with development and redevelopment projects slated for Kings Beach, Tahoe City, Truckee and Incline Village.

A packed crowd filled Blyth Arena for the figure skating event at the 1960 Squaw Valley Winter Games. Blyth Arena collapsed under the weight of snow in 1983, photo by Bill Briner, courtesy Squaw Valley

Olympic Allure

Despite the numerous reservations, many feel the idea of a Tahoe Olympics is accompanied by an undeniable excitement .

“I think it would be incredible to have something like that here,” says Truckee’s Daron Rahlves, a former Olympic and World Cup alpine ski racer. “We have a heritage of producing a lot of Olympians from this area. There’s good bloodline here. So it’s something that would be really cool.”

Wirth says that even thinking pragmatically, it’s hard not to get swept up in the emotion of an event that showcases the prowess and ambition of athletes around the globe. “Look, it’s called the Olympic spirit and it’s a true spirit,” Wirth says.

Jon Killoran is CEO of the Reno Tahoe Winter Games Coalition and he knows more than anyone about both the ambiguities in public opinion regarding the issue and the logistics required to host the Games. He worked closely with Tahoe officials and members of the USOC several years ago, when the committee was considering putting in a bid for hosting the Winter Games in either 2018 or 2022.

“We did some polling in 2010 and 2012 and we found there was majority support throughout the entire region—the three counties on the Nevada side and the three counties on the California side,” Killoran says. “In Tahoe, there is a lasting heritage of Olympic spirit.”

Killoran says that nearby cities would play a major factor in hosting different events and accommodating scores of visitors.

“The whole idea would be to have Lake Tahoe at the epicenter and both Sacramento and Reno playing key roles,” Wirth says.

Area support would lift the burden off Tahoe to build infrastructure sufficient to host opening and closing ceremonies, figure skating, hockey, speed skating and other events that would require stadium-style capacity. Instead, Tahoe could focus on hosting most of the major mountain events, like skiing and snowboarding.

Killoran says the construction necessary for those events could be done in a manner consistent with Lake Tahoe’s values of environmental stewardship. “I am confident that we can put forward a bid that is economically, socially and environmentally sound,” he says.

While other countries may have struggled balancing those three factors, he points to the Games in Salt Lake City as an example of how environmental stewardship, economic development and even the creation of affordable housing can intersect and be a net positive for a community.

“This could be a catalyst for a positive environmental situation,” he says.

The slalom ski race at the 1960 Squaw Valley Olympics was held on Exhibition, photo by Bill Briner, courtesy Squaw Valley

The slalom ski race at the 1960 Squaw Valley Olympics was held on Exhibition, photo by Bill Briner, courtesy Squaw Valley

Logistical Realities

Environmental factors aside, Tahoe would encounter some logistics problems, not the least of which is that many critics say area ski resorts lack the vertical feet necessary to host a men’s downhill ski race.

“That would be the hardest thing,” Rahlves says. “Where are you going to put a downhill?”

In 1960, Squaw hosted the men’s downhill, but the track does not fit current International Olympic Committee (IOC) specifications.

“Squaw is not sustained,” Rahlves says. “It doesn’t have the vertical; there’s just too much flat. Olympic Lady and KT, if they had a little more open terrain and vertical, they could do it there, but it wouldn’t pass as a men’s downhill.”

But Killoran says his office commissioned a study in 2010 that identified four to five different sites throughout the Basin capable of holding the men and women’s downhill. Separately, Wirth says his committee consulted a resort planner, who also found multiple options to install a downhill course. Both Wirth and Killoran declined to give specifics in regard to potential routes.

American World Cup skier and Squaw Valley product Travis Ganong, however, is a proponent of bringing the Games back to Tahoe. He says he met with a development group out of Park City Utah, and they mapped out at least three routes at Squaw Valley.

“There are amazing options for a downhill here,” says Ganong, who is expected to be among the top contenders in the event at the PyeongChang Winter Games this February. “It’s a little tricky with the vertical; it’s the minimum vertical to have a downhill. But it works.”

Ganong even worked with the development group to craft a world-class route.

“The one I designed is similar to Wengen [Switzerland], the classic Lauberhorn downhill, which is really long and has some flatter sections, but then also really steep, unique features too,” Ganong says. “To do it, it would take a lot of snowmaking and fencing and some earth work. But it would be a classic downhill.”

Alpine events are not the only consideration. Olympic specifications state that cross-country events must not be held at above 5,900 feet in elevation. Currently, Truckee-Tahoe’s extensive network of cross-country trails are all above that threshold, but Wirth says officials have likewise identified at least two areas capable of hosting that event.

Lastly, Killoran says similar studies have identified several places throughout the region capable of facilitating the construction of a sliding center that would host all the sledding events like the bobsled, the luge and the skeleton.

“We’ve done the inventorying of what is available and what is not available as part of the work when we were preparing for the 2018 or 2022 bid,” Killoran says, without pinpointing exact construction locales. “For us, at this point, there are multiple options.”

The Red Dog run at Squaw Valley was the site of the women’s giant slalom course for the 2013 and 2014 U.S. Alpine Championships, as well as a 2017 World Cup slalom event, photo by Sarah Brunson, courtesy USSA

The Red Dog run at Squaw Valley was the site of the women’s giant slalom course for the 2013 and 2014 U.S. Alpine Championships, as well as a 2017 World Cup slalom event, photo by Sarah Brunson, courtesy USSA

Costs of the Games

Antonucci says that if the Olympics were to return to Tahoe, the region must do a better job of post-Games maintenance of facilities like the ice rink and sledding center than the first time around.

“What happened after the [1960 Winter Games] was the real tragedy of the Olympics,” Antonucci says.

In the late 1950s, in the run-up to the Squaw Valley Olympics, the influx of investment cash allowed Cushing to build a world-class ski jump and the famous Blyth Arena, which hosted the opening and closing ceremonies, the hockey tournament and many of the skating events.

Afterward, California State Parks let those facilities languish; the ski jump was eventually dismantled and Blyth Arena collapsed under the weight of snow in March 1983. Antonucci believes those facilities could have been used to attract more economic activity to the region had the upkeep been adequate.

The IOC has been taking steps to make the Olympics a better deal for host cities ever since a December 2014 session in Monaco when, under the new leadership of president Thomas Bach, an enormous reforms package was passed.

Part of those reforms was an emphasis on reducing the cost of bidding, encouraging host cities to build facilities with an eye toward sustainability and allowing those cities greater flexibility in the use of already existing facilities.

The fact that Salt Lake City still maintains the majority of the Olympic facilities it built for the 2002 Winter Olympics could give it a leg up over Denver and Reno–Tahoe in the bidding process as situated in the context of the more sustainability-minded IOC.

The IOC reforms may be especially important in the wake of reports that Rio de Janeiro expended more than $20 billion to build the necessary infrastructure to host the 2016 Summer Olympics. Questions linger about whether that country will ever see an adequate return on investment, while social costs of the Olympics saw low-income residents displaced by construction of facilities that spawned protests and political unrest in Brazil.

In fact, most countries see steep economic costs due to the Games.

According to a 2016 study conducted by the New York City–based Council of Foreign Relations called “The Economics of Hosting the Olympic Games,” Los Angeles, which hosted in 1984, is the only city in the modern era to make a profit hosting the Games.

Greece’s billions in debt connected to hosting the 2004 Summer Olympics literally bankrupted the country. The Sochi Games held in Russia will cost that country’s taxpayers about $1 billion annually for the foreseeable future.

According to the study, the 2010 Vancouver Winter Games cost $7.6 billion to produce, while only generating $2.8 billion; the London 2012 Summer Games generated $5.2 billion compared with $18 billion in costs.

These numbers don’t even reflect the large-scale facilities that are built and subsequently abandoned, sometimes falling into disrepair. For example, Beijing’s famed Bird’s Nest stadium cost $460 million to construct, has a $10 million annual price tag in maintenance and sits unused.

Wirth and others think Tahoe can learn from these cautionary tales and ensure the building is responsible and that new facilities are versatile enough to be used even after the Games are over.

“There are examples of how to do it right,” Wirth says. “In Salt Lake City and Park City, there are venues that are still actively used.”

For Antonucci, his support for future Games is dependent on several factors. One is community support. “You’re never going to get 100 percent consensus but there has to be broad support,” he says. “Not just the business community, but at the grassroots level.”

He also, as other local leaders have mentioned, would want to see Olympic investment leave the region better off than it began, with transit and redevelopment dollars helping economic, social and environmental outcomes.

Finally, there needs to be a lasting commitment to not only the construction but upkeep of facilities like the ski jump and sledding center, which Antonucci believes could function as tourist magnets and economic drivers if properly built and looked after.

“It’s possible,” he says.

For the present, that’s all it is—a possibility. The USOC wants a Winter Games for the United States, but the athletic organization is currently preparing for more pressing matters. Furthermore, should the USOC select Tahoe, the region would have to compete with global winter havens like Innsbruck, Austria and Calgary, Canada. Still, for better or worse, Tahoe’s hat is in the ring.

Matthew Renda is a Santa Cruz–based writer. Tahoe Quarterly editor Sylas Wright contributed to this article.

No Comments