02 Dec Creating a Forest for the Future

For decades forest restoration projects have addressed small areas, but now land managers are thinking much bigger

Problems in Lake Tahoe’s forests have been growing for a long time. Now, those involved in solving them are thinking big.

A project that’s the first of its kind for the Tahoe Basin is now being pursued by a broad-based coalition of scientists, land managers and private interests, preparing the forest for the future amid the challenges of a warming climate, drought, attacking insects and the threat of catastrophic wildfires.

“The scale of the problem is too big to approach in a piecemeal way,” says Sarah Di Vittorio, Northern California program manager for the National Forest Foundation. The nonprofit organization is the project manager and facilitator for the Lake Tahoe West Restoration Partnership.

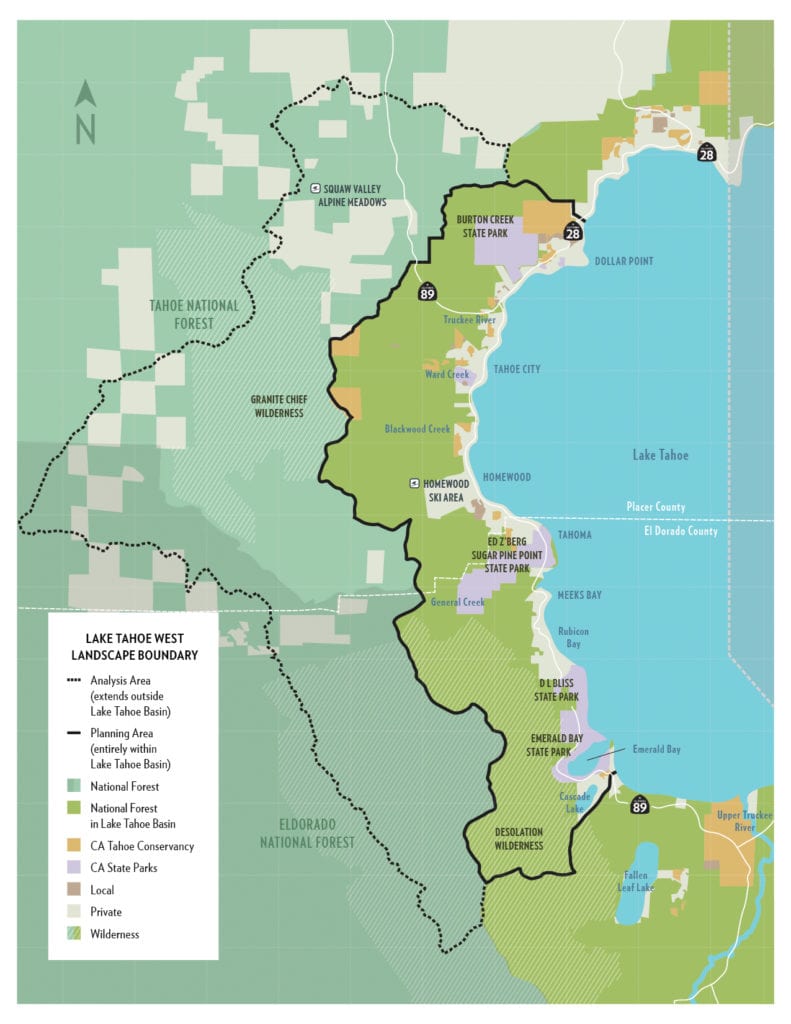

The project encompasses a huge swath of forested terrain from the shore of Emerald Bay north to Dollar Point and Squaw Valley, which the partners intend to restore by thinning over-thick forests, controlled burning and other measures. The majority of this 60,000-acre area is National Forest land managed by the U.S. Forest Service as the Lake Tahoe Basin Management Unit and Desolation Wilderness. It also includes several state parks, private lands and numerous parcels managed by the California Tahoe Conservancy.

In the first phase of the project, experts assessed current conditions not only within the 60,000 acres, but also adjoining forests west of the Basin.

In all, they studied more than 153,000 acres—nearly 240 square miles.

The idea is to look at forest health restoration on a landscape scale, not in plots of a few hundred or a few thousand acres, as has been the practice of the past.

“We have to think about moving beyond that to a much larger scale,” says Brian Garrett, urban forest program manager for the U.S. Forest Service’s Lake Tahoe unit. The Forest Service, which manages the vast majority of land being studied under the project, hopes to pick up the pace and scale of needed forest treatment across the country.

“I think we’re on the right path,” Garrett says of the local strategy. “This puts us in a good position to start looking at that larger landscape.”

Paying for the Past

Problems in Tahoe’s forests date back well over a century. In the 1850s during the Comstock era, as armies of prospectors pulled riches in silver and gold from Nevada’s Virginia Range, Tahoe’s healthy, diverse forests were clear-cut to provide lumber to shore up mines.

What grew back was an unhealthy, even-aged forest that is hugely susceptible to fires, drought and attack by bark beetles. The situation was worsened by a century of active suppression of any fires that did start, resulting in increasingly unhealthy conditions in the woods.

“Most of our West Shore forest has way too many trees,” Garrett says. “What we have is an overstocked, very dense forest landscape.”

Experts have long been concerned about the situation. In 1997, during the first Lake Tahoe Summit, restoring health to Tahoe’s forests was made a top priority and federal funds began flowing to the area to help make that happen.

And much has been accomplished. Over the last 20 years, some 75,000 acres of forests were thinned to reduce the risk posed by fires to vulnerable neighborhoods. Needed thinning along the so-called wildland-urban interface is expected to be completed in a few years.

But experts recognize the need to look deeper into the forest, addressing not only fire danger but broader forest health, wildlife habitat, water quality and other issues linked to that larger landscape.

The Lake Tahoe West project seeks to prevent the massive die-offs that have decimated forests south of Tahoe, photo by Sylas Wright

Collaborative Action

Discussions regarding the Lake Tahoe West Restoration Partnership started in 2016, with participants including the National Forest Foundation, the Forest Service, Tahoe Regional Planning Agency, California water quality officials, the California Tahoe Conservancy, California State Parks and Homewood Mountain Resort, among others.

“What we’re trying to do is to plan a project that goes across all the different jurisdictions,” says Christina Restaino, forest health program manager for the Tahoe Regional Planning Agency. “We’re really taking a very collaborative approach with this. We have all the different players at the table and that’s a real key part of this.”

Bringing everyone together, Restaino says, not only streamlines the planning and permitting process, it also helps avoid legal conflicts that might come with multiple smaller projects in the same region.

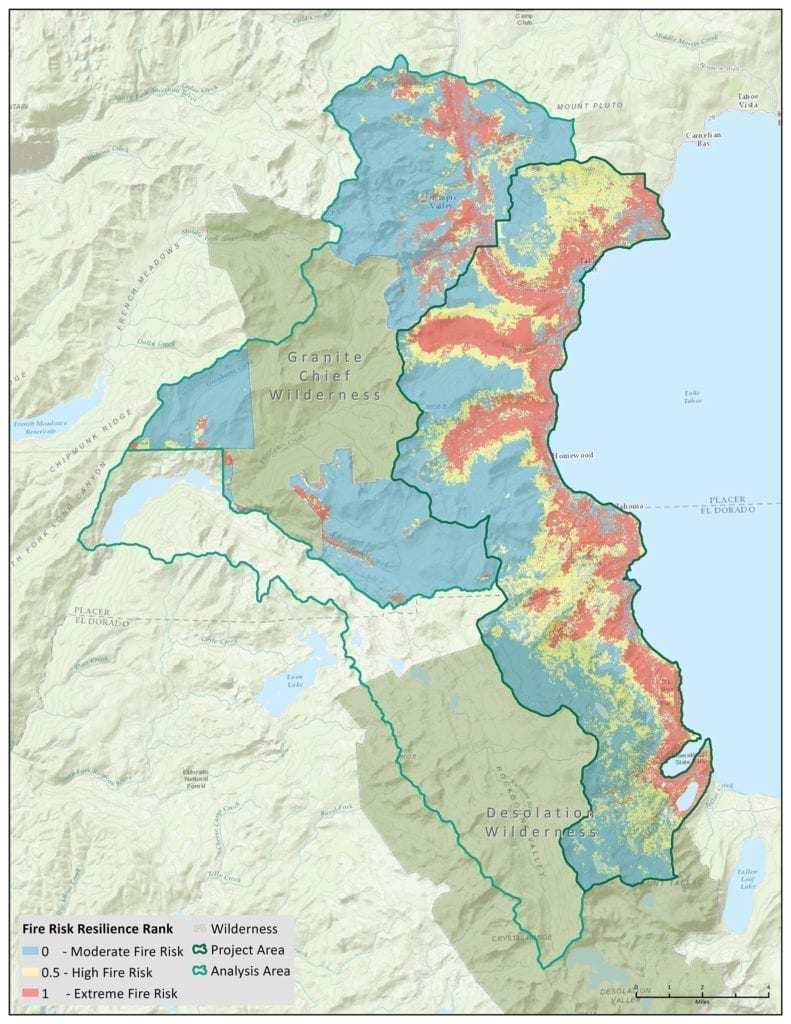

These combined efforts reached a milestone in December 2017 when the partnership completed a “Landscape Resilience Assessment”—a report that identified existing conditions within the targeted area of Tahoe’s West Shore. Findings were not surprising.

“It’s definitely at risk of catastrophic fire,” Restaino says.

Partners are now developing a strategy to restore the landscape. Working with scientists, they are modeling the effects of different potential management approaches to identify what types of restoration are needed now to produce a resilient forest. The strategy, expected to be released in March 2019, will also evaluate economic costs and benefits and community health and safety. Treatments have already begun in some areas, particularly those near homes.

Thousands of acres will likely be targeted for tree thinning. Prescribed fire may be recommended for places where it can be conducted safety, returning fire’s natural role to an ecosystem where it has been excluded for a century. Meadows and streams will be recommended for restoration, with a high priority placed on the health of wildlife habitat and the protection of water quality.

A Biomass Breakthrough?

The sheer scale of Lake Tahoe West could also help remove one of the major obstacles faced by forest restoration projects in recent years at Tahoe and across the Sierra—what to do with the small trees and woody “biomass” that must be removed from treated terrain.

Over the last several decades, lumber mills across the Sierra have closed, making the transport of trees removed during restoration work economically unfeasible. Small trees and brush associated with such projects only compound the issue.

But with Lake Tahoe West expected to produce a steady stream of small-mass material, the increased supply to the market could provide a much-needed boost to the Sierra’s lacking biomass industry, Restaino says.

“By increasing scale, we are encouraging improving the economics for this,” agrees Forest Schafer, forest science and management coordinator for the California Tahoe Conservancy.

One encouraging development, Schafer says, comes with the recent acquisition by American Renewable Power of a shuttered biomass plant and sawmill in Loyalton, north of Truckee. The facility was retrofitted into a modern co-generation plant that converts biomass to energy and is now operating.

That co-generation plant offers a “real promising location” when it comes to potential solutions for biomass produced from forest restoration work like that envisioned in the Lake Tahoe West project, Schafer says.

The need to treat the Sierra’s ailing forests to avoid devastating wildfires has become so obvious that changes in how biomass is handled are plainly necessary, Schafer says.

“It’s still challenging to have an economically feasible way to utilize all this small material, but I do feel we are at a point that it’s close because the need is so clear,” Schafer says. “We seem to be at a tipping point.”

Restoring Resilience

Lake Tahoe West is one of many such large-scale forest restoration projects being pursued across the country, with climate change adding urgency to the need for such work. As the climate warms, forests will increasingly be impacted by fire, drought, bark beetle infestation and resulting tree mortality.

“The goal is to restore the resilience of the landscape to disturbance,” says the National Forest Foundation’s Di Vittorio. “We know there are going to be larger impacts in the future. The forest can either respond or it can’t. The goal is to put the landscape on a trajectory to a functioning, healthy state.”

Participants in the project agree that Tahoe’s West Shore is just one area of Lake Tahoe that could significantly benefit from landscape-scale restoration. Other projects could occur to the north, south and east of the lake.

Says Di Vittorio: “The buzz phrase is after Lake Tahoe West, let’s do Lake Tahoe rest.”

Jeff DeLong is a freelance writer based in Incline Village.

No Comments