01 Dec A Legacy Set in Stone

Nearly four decades after Jake Smith perished in the 1982 Alpine Meadows avalanche, an iconic Tahoe peak carries on his story

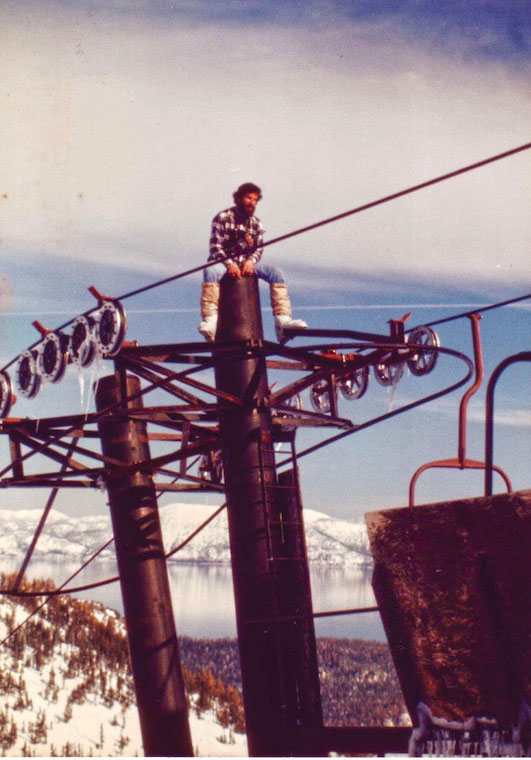

Jake Smith, sporting white ski boots and blue jeans, sits atop a lift tower at Alpine Meadows, photo by Billy Davis

In the winter of 1973, Jake Smith left his job-with-a-future and drove his flat-land car through a storm to Tahoe. Alpine Meadows was hiring for the spring. Lodge maintenance was a toehold in the mountains. He found a small cabin to rent on the West Shore, bought his first pair of Sorels, and started saving for snow tires. He missed nothing of the city.

Jake had a quick humor that made light of the cleaning and pounding of his new job. He made friends easily. Although he was not yet a good skier, his attitude of reckless abandonment forced him to learn quickly. He had not been in Tahoe long before he knew with certainty that these mountains were his place.

Spring ended, the snow melted and Jake found a summer job as a carpenter. When the snow fell again, Alpine hired him as a lift operator, then made him “heater man”—in charge of keeping the lift-shack propane heaters lit and running. These were literal “shacks” at the time, snow blowing through cracks in the walls. Yet, heater man was a coveted scam. Jake was adept at the job’s minimal requirements, like stuffing the cracks with magazine pages, which bought him plenty of time to find fresh powder, whether by skis or snowmobile, between every maintenance stop.

But his bosses liked him. They tried to make Jake assistant lift foreman, but he wasn’t interested in becoming management. Once, when Mountain Manager Bernie Kingery bawled him out in a meeting for not being efficient, Jake replied, “Oh, I thought you said I should ‘be a fishin’.”

Ski areas in those days were not the corporate-owned entities of today. Most were owned by a single, strong personality and run like tiny fiefdoms. At some resorts, it was the founder in charge, the guy who literally moved first dirt, like Mammoth Mountain’s Dave McCoy. At most resorts, it was the phase-two investor who bought out the founder (or in the case of Heavenly Valley, the lawyer who created a series of limited partnerships to force out resort founder Chris Kuraisa). But all these men—the ski industry was probably 90 percent men at the time— shared a motivation for being involved: a passion for skiing down mountains. All except one: Alpine Meadows’ owner, Nick Badami.

“I bought Alpine Meadows because of my son’s love for skiing, not mine,” Badami was fond of saying in the decades that followed, “but then I fell in love with the ski industry.”

A former board chairman of BVD Corporation (underwear worn by every American G.I. during World War II), Badami later bought Park City ski resort and became “one of the most influential leaders in the history of the U.S. Ski Team” (as stated in his 2008 obit). He was “the smartest guy in the room,” but he ran Alpine Meadows, hands-on, like a benevolent Italian godfather (his middle name was Dante). Alpine was full of talent, but there was also room in the family for an iconoclast like Jake.

Instead of management, Jake landed on trail crew—a haven for those capable of responsibility but without necessarily a hankering for it. Soon he was put on year-round duty.

Disaster in the Making

The late 1970s included some of the worst drought winters in Tahoe history. But as the ’80s rolled around, it started to snow again. Hard. Historic.

On March 27, 1982, a tightly packed series of cold storms hit Tahoe. Snowfall soon averaged over an inch an hour around the clock. By morning on March 31, over 8 feet had fallen at the Alpine Meadows base lodge, with who knows how much more on the high peaks. Resort staff deserted the place due to the danger. Bob Moore of the U.S. Forest Service snowmobiled in and trained the resort’s 75mm howitzer gun on the slide paths above the resort, lobbing exploding shell after shell. Alpine ski patrol was given access by neighboring Squaw Valley to the ridgeline between the resorts, throwing bombs down on the avalanche routes they could access above the road and base area. But in the swirl of the 100-plus-mile-per-hour winds, no one could see for sure whether the bombs were sluffing off snow in “controlled” slides, or if 10 feet of snow or more was accumulating.

Midday on the 31st, ski patrol was again set to attack the high ridges. Mountain Manager Kingery directed operations from his office in the Summit Terminal Building. Jake Smith, volunteering for road closure and spotting duties, was at his side. The resort should have been otherwise evacuated, but lift operator Anna Conrad and her boyfriend, Frank Yeatman, hiked in from her nearby condo to get something from her locker. A group staying nearby decided to fight cabin fever and attempt a walk-swim through the 8 feet of fresh powder in the resort’s lower parking lot.

No one could have known that the avalanche charges and howitzer shots exploding on the ridges above the base area had no effect. Snow piled there with the entire four days of depth, packed into drifts by hurricane-force winds.

Jake knew the danger. Two months earlier, he had climbed and skied in a fresh avalanche path that had roared down a then-unnamed peak north of Emerald Bay, killing a camper and uprooting a 100-year-old forest in a half-mile-wide swath. Now, with the patrolmen moving toward the ridge, Jake walked out into the blizzard and revved his snowmobile toward the entrance of the parking lot. Once there, he sat for only a minute or two, looking up into a universe of white—snowflakes making fleeting imprints on his goggle lens—before out of the blur he saw it.

“Here she comes,” he yelled into his walkie-talkie and spun his snowmobile toward the bridge.

“What is it?” replied Kingery in the instant before the avalanche exploded through the building, blowing him and the walls out 40 yards before burying him.

Jake bent over the snowmobile at full throttle, life pumped through every artery, and made it to the bridge halfway across the valley before the slide took him down in a cold embrace.

The Summit Terminal Building after the 1982 Alpine Meadows avalanche, photo by Chaco Mohler

Seeking a Fitting Tribute

The snow melted. The seven dead were buried. The buildings were rebuilt. But some looked for more meaning. Jake’s older brother, Dennis, thought of that unnamed peak where the earlier avalanche had swept across Highway 89.

The Summit Terminal Building looking northwest after the avalanche. Rescuers would later find Anna Conrad alive under all the snow and wreckage, photo by Chaco Mohler

Soon a petition made its rounds to have the mountain named “Jake’s Peak.” Dennis and his wife at the time, Celest Fournier, a ski patroller, proposed that a display be built off Highway 89 near the slide path, educating on avalanche danger and other backcountry topics. Over 5,000 residents signed the petition. Dennis and Celest began traveling the bureaucratic channels of the four county, state and national agencies that have a say in what tower of rock gets what name on our maps.

Some questioned the naming of a peak for a “ski bum.” Nearby peaks have Native American-inspired names, or those of early settlers, prominent bankers and parts of a woman’s anatomy. Dennis argued that it was appropriate to name a peak after one of the many who help make these mountains safe and enjoyable for the rest of us.

In April of 1986, Dennis and Celest traveled to Washington D.C. and spoke in front of the seven-person National Board of Geographic Names panel. Jake’s Peak fits every necessary criteria, Celest argued, including educational purpose: “It will create a monument for avalanche awareness.”

“Everything I did was guided by thinking of what Jake would have wanted,” says his brother, “a way to warn others of the danger.” The board approved. Nick Badami offered to pay 100 percent of the costs of a roadside pullout and educational kiosk. Instead, the project ran into bureaucratic issues with regulatory agencies (not uncommon in that era) and died a slow death despite the enthusiastic support of Badami and others.

Says Dennis, “The location Caltrans had chosen for it was right in the middle of the avalanche path, so maybe it was best it was never built… ‘If it’s snowing and you’re reading this, run!’”

But Dennis believes the initial dream of the educational kiosk—located in a safer spot—might eventually be realized through the efforts of his and Celest’s two sons.

Searching the wreckage of the Summit Terminal Building blown out by the avalanche, approximately where the body of Alpine Meadows Mountain Manager Bernie Kingery was found days later, photo by Chaco Mohler

Homage to a Life Lost

During the five years that it took to name Jake’s Peak—which was officially adopted in 1986—Dennis would lead dawn climbs and ski descents of the mountain, each a celebration of Jake’s life, but also a moment to reflect on other lives lost, and our own going forward. An hour of climbing up a mountain, moving from dark to first light, each deep breath matching each steep step, has a purifying effect on the soul (even when that soul starts with a hangover and dead flashlight battery). At sunrise at the summit, it doesn’t matter in what state you start, the veil thins between this and other worlds.

Atop a Tahoe summit, one questions why we, in our vanity, believe we can put permanent names to these peaks. Their massive crowns will certainly be here long after we two-legged creatures end our reign.

But if we must label and name, why not recognize a Tahoe “common man” who was anything but common? You know the cliché: Your Tahoe bartender and carpenter both have advanced degrees. But an essential lifeblood of our communities is also made up of men and women who “match our mountains,” the ski resort workers, backcountry rangers and others who put themselves in danger and discomfort for our safety.

On one of those long-ago spring dawns, Dennis stood next to a small plaque that read “Jake’s Peak,” which he had placed in the rocks at the summit. “His soul hangs out here,” he said. Around him stood ski patrollers, trail crew and others who had decided to forgo the modern combat for “success” and measure their lives against the seasons of the high country. Few were churchgoers, but atop this immensity of rock there existed a reverence to match any religious service.

We stood mostly quiet while the snow softened. Someone finally said, “Well?” The last beer was shared, can crushed and put in a pack. One by one we pushed off to dance down the mountainside, skis pointed toward our lives below, leaning forward in our boots.

Chaco Mohler is former publisher of Tahoe Quarterly and the magazine’s first editor-in-chief. This piece is adapted from his 1985 feature in Powder magazine.

Susie Whitcomb

Posted at 21:35h, 12 DecemberThanks for bringing this story back! I never tire of those memories. I had no idea Dennis and Celeste had fought so hard for such a great cause!

Barbara Kuvet

Posted at 22:25h, 12 DecemberWow!! This story!! A tribute and time in history and for some reason I don’t remember that tragedy. I arrived to Northern California in 1976 by way of the Gray Rabbit, an underground coast to coast hippie bus service from NY to SF. I was young and had my head in the clouds. I found Nevada City in 1977, spent spring & summer of ’78 introducing myself to the backcountry of the Tahoe National Forest and in 1980 I permanently planted my feet in the red dirt of Nevada County. New to the Sierra, with roots to Lake Placid and the Adirondacks, I knew that finding Alpine I had found my mountain. Back then the word on the street was that Alpine was known as the friendly mountain, unlike the vibe of it’s neighbor. Around 1985 the husband worked for the Forest Service in fire and got to attend the Howitzer training at Alpine. He introduced my brother to working in fire. The next thing my brother knew he was living that life… Hotshot by summer and bopping chairs at Alpine by winter. Seemed lots of Forest Service folk lived this lifestyle. Your story stirred up lots of memories. Thanks for sharing the history, the tragedy and honoring those hearty passionate folks who pioneered the big mountain ski scene in this neck of the woods.

Tom

Posted at 08:17h, 13 DecemberThanks for this Chaco!

Julie Vignolo

Posted at 11:06h, 17 DecemberWhat a beautiful tribute to my Uncle Jake ❤️ He will always be a legend in our family (his great nephew “Jake” was named after him!) and it is so wonderful to read a story from the perspective of others. I hope his legacy lives on and the story of that terrible continues to be shared. His soul is most certainly free atop that mountain peak. Thank you again for your beautiful words.

Dennis W Smith

Posted at 15:06h, 17 DecemberThanks Chaco, just a note to add , I am so proud all of the avalanche forcasters and all of you whom support them in their work.The idea behind the nameing of Jake’s Peak was and still is ,avalanche and mountain survival awareness . Please help support our future effort ,to create a small trail head (and parking area) near the north flank of the base of Jakes.this may become a proposal soon Stay safe Dennis Smith

Ron Blickle

Posted at 11:21h, 05 JanuaryWhat ever happened to Anna Conrad who was found several days later alive in that warming shack? As I recall she had severe frostbite and lost a leg and some other extremities. Another tragic story with a better ending.

Tahoe Quarterly

Posted at 11:29h, 05 JanuaryAnna Conrad’s story is remarkable indeed, Ron. She now lives in Mammoth Lakes: https://www.sacbee.com/sports/outdoors/article64135517.html

Rico Cruz

Posted at 17:13h, 05 JanuaryThe book, A Wall of White, is an amazing account of Anna Conrad’s ordeal. A great read

Paul Zarubin

Posted at 07:55h, 06 JanuaryThanks Chaco, this article also stirred up memories from that day. I was a volunteer with Donner Summit Fire and we were transporting a patient from Donner Summit when the Alpine slide happened. We were asked to stand by Tahoe Forest to assist if needed. I’ll never forget when the first survivor arrived to the hospital. I helped him out of the ambulance but was shocked when it turned out to be my cousin Jeff Skover. His story still gives me chicken skin. He was standing in the same room with Bernie when he heard the radio transmission from Jake. His last memory was hearing the roar of wind and flying through the air wondering how he was going to go through the wall. The rescuers found Jeff right away because he was only partially buried, in fact he was found directly above where they eventually found Bernie. His only injury was a head laceration and loss of consciousness. I had no idea that Jeff was working at Alpine that winter, like so many others he took a security job so he could be a ski bum for a winter. Great story, thank you.

Kathe Foster

Posted at 08:52h, 06 JanuaryHi Chaco – Jake was my brother . . . I am Denny and Jake’s Big Sister, Kathe. You have described Jake perfectly- your tribute felt like a visit with him . . . who I miss every day. Jake has 2 nephews named after him ~ our son born 11 months before the avalanche (so Jake met him!), and our grandson now 13 who learns more about him from us, and now you! Thank you so much for this wonderful article~

Joe Pettit

Posted at 15:09h, 06 JanuaryChaco, thank you for writing that story. Living in Tahoe (north and south shores) for 30 years, I knew Jake’s Peak, but nothing about the story or person for whom it was namesaked. I even named my son Jake with some influence from that peak. Your reference to some of the old guard of resort owners flashed back memories of my time working in marketing for Northstar and Kirkwood in the late 80s and 90s. A bygone era I was fortunate to experience the tail end of…before it all became so corporate. I’ll hoist an IPA and toast Jake Smith, who I never knew personally, but from your poignant description, I knew his kind. Thanks again Chaco! Joe Pettit

Chaco Mohler

Posted at 12:11h, 08 JanuaryThank you to all who responded with kind words and more information about Jake and the Alpine Avalanche. Be well!

Thom Orsi

Posted at 14:59h, 09 JanuaryThanks Chaco !! You nailed it, my friend. I still think of Jake and the great times we had together. That day is forever etched into my life and my soul.

Bob Ward (Charbonneau)

Posted at 19:13h, 09 JanuaryHearing what he replied to Bernie, reminds me of when we were building the commercial building behind clementines we were in the bar and the bartender sat a plate of onion rings in front of Jake we ate em, then the bartender went to charge us Jake said we did not order them he thought they were free the bartender said no we had ordered them, Jake said we didn’t order onion rings he had asked how Paul Bunyan sings, have quite a few more even a couple of Bill Patterson’s on the same project!!!!!!

Chaco Mohler

Posted at 17:58h, 10 JanuaryLove it!

Cheryl

Posted at 13:57h, 27 JanuaryI too love and respect our majestic mountains. Thank you for this story, which I have never heard. I love hearing and learning about the history of our beautiful community.

john moore

Posted at 18:14h, 12 FebruaryWell written tribute to a great character. Hard to believe almost forty years has passed.

Katherine Hayes Rodriguez

Posted at 13:04h, 18 OctoberNice summary of the truth. Thanks, Chaco!