25 Jun Legends of the Fall

Aaron Fleenor flips off a bridge over the Yuba River, photo by Ryan Salm

Aaron Fleenor flips off a bridge over the Yuba River, photo by Ryan Salm

In Tahoe and beyond, the adrenaline-inducing sport of cliff jumping is gaining steam

A granite cliff as high as a 10-story building falls away beneath my feet to the shimmering blue of Lake Tahoe. My backpack scrapes against the rock as I descend to a precarious notch in this vertical landscape. The bulky camera gear adds difficulty to each maneuver, and I’m wishing I left it behind. But it’s the reason I’m here—to capture the mind-bending display of athleticism and acrobatics that I’m about to witness.

Freestyle cliff jumper Brandon Beck of Kings Beach, donning a wetsuit under a T-shirt and board shorts, casually pops over and offers to carry my bag. Though I decline, I do pass it across an exposed section before leaping over.

Beck continues his scramble to the launch point—a small natural platform protruding from the cliff face—when suddenly, a startled outburst pierces the morning calm. Beck curses under his breath and laughs. A large goose tucked in a rocky nook had snapped at him, nearly causing him to lose his grip. He shakes off the close encounter and proceeds upward.

In the world of a cliff jumper, there’s no telling where danger may lurk.

Brandon Beck of Kings Beach jumps from a rock during a morning session on Tahoe’s West Shore, photo by Ryan Salm

Brandon Beck of Kings Beach jumps from a rock during a morning session on Tahoe’s West Shore, photo by Ryan Salm

Underground Movement

Cliff jumping, or cliff diving, is separated into two distinct styles.

The competitive side of the sport can be seen in the Red Bull Cliff Diving series, where athletes jump off platforms up to 27 meters high (nearly 90 feet) in some of the most exotic places on earth. It follows the traditional high diving format mixed with rules from the Red Bull Diving Sportive Committee. At the culmination of the season, the top-ranked divers are awarded the King Kahekili Trophy, named in honor of the man believed to have created the sport.

The second is dubbed “underground” by those involved in the scene. The underground side removes the competitive element and adds a mixture of adventure, location scouting, free climbing and uneven takeoffs.

Like the cliff diving sites used by the pros, the underground venues are often spectacular locations, overlooking gorgeous bodies of water in dramatic mountain settings. And while some underground jumpers may not have a background in diving or gymnastics, they have created their own unique flair by integrating ski- and snowboard-style grabs and tricks.

Tahoe, given its abundance of talented, adrenaline-seeking skiers and snowboarders—and towering cliffs over water—has become a West Coast epicenter for this burgeoning sport.

“It’s Northern California as a whole that brings people here to jump, and it’s Tahoe’s ski areas that influence the vast amount of style,” says Beck. “The ski culture and the attitude around here seems to bring out this new summertime scene of cliff jumping. Tahoe’s alpine paradise is a one-of-a-kind place that has attracted extreme athletes for generations.”

Brandon Beck with his 6-year-old son Carter, photo by Ryan Salm

Brandon Beck with his 6-year-old son Carter, photo by Ryan Salm

But while Tahoe is increasingly becoming a hub for cliff jumpers, the shockwaves of this awe-inspiring sport are rippling across the country.

“There are scenes all over America popping in up in all corners,” Mike Wilson, a former Tahoe resident and cliff jumping extraordinaire, says in a cellphone interview from Alaska, where he’s taking a Wilderness EMT course. “Through YouTube, all these crews are intermingling and feed off one another.”

A professional-level skier, Wilson is perhaps best known for his viral Internet edits, which document his hair-raising, acrobatic jumps off lofty cliffs and rope swings. In one video, Wilson repeatedly launches quadruple backflips from a rope some 100 feet above Tahoe’s West Shore. In another, he performs textbook triple backflips off a similar setup high above the Truckee River, drawing oohs and aahs from weekenders floating by on rubber rafts.

Although Wilson makes these crowd-pleasing feats look easy, he’s quick to warn that they’re not—and that anyone thinking of trying their hand at the sport should start small.

“I try to inspire people to do fun things and do them well, but I am not out to promote craziness. What I do is calculated,” says Wilson, who now resides in Bermuda. “It’s not about the rush. The rush means I am not prepared and qualified to jump off that cliff. It’s about approaching things sensibly. The key is to get into it through baby steps and work your way up through those steps. The key is to be smart and be prepared.”

Colton Shaff brings his own style to D.L. Bliss State Park as Travis Sims watches comfortably in his bathrobe, photo by Ryan Salm

Colton Shaff brings his own style to D.L. Bliss State Park as Travis Sims watches comfortably in his bathrobe, photo by Ryan Salm

Jumping Bliss

We began our hike into D.L. Bliss State Park just after 5 a.m.—Beck, his 6-year-old son Carter and Colton Shaff, a 20-year-old UNR student and ripping Squaw Valley skier. The goal was to get shots of Shaff and Beck hucking their bodies off various cliffs into Tahoe’s chilly May waters.

In the weeks prior, I found myself on a group text with the subject line “Tahoe Cliff Jumpers.” There were about nine random numbers, no names on my end, and a bunch of back-and-forth messages about going jumping near Mt. Shasta; being worried about cliff jumping the morning after Cinco de Mayo; some profanity; a photo of someone at a party; and at least one comment about a recent injury caused by a backflip off a table, which cast doubt over one guy’s ability to jump that week.

Beck pointed out the now renowned rope swing that Wilson installed a couple years prior. Meticulously assembled high above Tahoe’s rocky shoreline, Beck and others have also used the swing to showcase their aerial skills to the masses through online videos. Those involved in Tahoe’s cliff jumping scene hold Wilson in high regard for his contributions.

As we discussed the shot plan, another cliff jumper and Kings Beach resident, Travis Sims, arrived. At first sight, he was an anomaly. While the others wore wetsuits and boards shorts, Sims arrived in a bathrobe and no wetsuit. Not only that, he climbed effortlessly down the rocks in flip-flops.

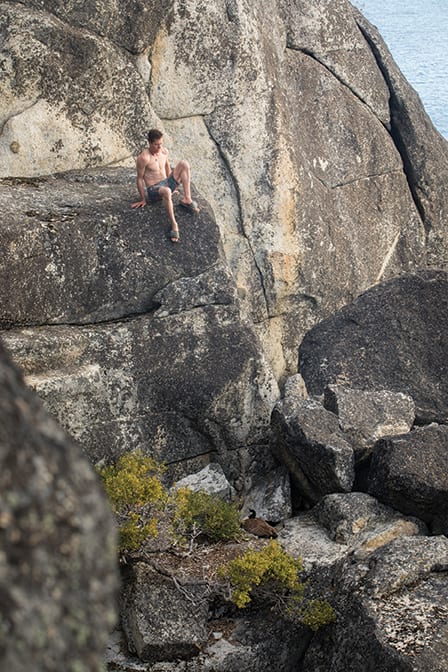

Travis Sims down climbs above an angry goose, photo by Ryan Salm

The morning sun lit up the granite cliffs as the trio climbed into position and readied for takeoff. I could see Shaff running through a checklist in his head. It was his first time jumping this spot. Beck gave the countdown and dove straight off head first. About three quarters of the way down he tucked his head, flipped over and landed feet first. Shaff followed with a massive gainer.

Last up was Sims. As he dove from the high perch—arms gracefully splayed out, feet together, toes pointed—I thought I was watching a professional diver. I wasn’t far off. Simms dove for the Metro State University (Denver) and Colorado Mesa University dive teams. His life is currently centered around the sport.

“I love cliff jumping because it’s the ultimate escape from reality and stress,” he explains. “It’s the most wild feeling in the world being able to trust yourself to land safely from such tall heights. My goals are to push the limits of how high I am able to go. So far my highest is 130 feet, and I am planning to go bigger.”

In this underground scene, all styles are welcome, as long as you make it your own.

Travis Sims, a former college diver, demonstrates his form over Lake Tahoe, photo by Ryan Salm

Travis Sims, a former college diver, demonstrates his form over Lake Tahoe, photo by Ryan Salm

Cliff Jumping Origins

Cliff jumping is arguably the world’s oldest extreme sport, with origins dating back to 1770.

As legend goes, Hawaiian ruler King Kahekili challenged his warriors to jump off a ledge on the southern coast of the island of Lanai into crashing waves and shallow depths. This initiation rite was a way to demonstrate loyalty and bravado to the king, who was known himself for his skillful execution of “lele kawa”—which roughly translates to “leaping feet first from high cliffs and entering the water without a splash.”

The daring jumps evolved into a Hawaiian competition under King Kamehameha a generation later and spread to other parts of the world in the following centuries.

The sport gained considerable popularity in the twentieth century.

High diving, then called “fancy diving,” debuted at the Olympics in 1904, while modern cliff diving is said to have started in 1934 when 13-year-old Enrique Apac Rios jumped from La Quebrada in Acapulco, Mexico. The site is now among the most famous in the world for cliff jumping, with divers jumping into shallow, breaking surf from heights exceeding 145 feet.

Area local Aaron Fleenor backflips from a bridge near Nevada City, photo by Ryan Salm

Area local Aaron Fleenor backflips from a bridge near Nevada City, photo by Ryan Salm

Hunting for Cliffs

I carpooled to various jump sites over the course of the week on the Yuba River, Frenchman Lake and at home in Tahoe. I met a bunch of the Tahoe crew.

One afternoon, I jumped in the car with Sims, Hope Lane and local backflipping specialist Zach Steele en route to the Nevada City area. Known for his big-air antics on skis, Steele made a name for himself in the cliff jumping community when he threw a double cork 1260 an unbelievable 125 feet off Havasupai Falls in Arizona. But on this day, he would be shooting video while recovering from a knee injury.

It’s one thing to walk down to the river, drink beers and have a picnic. It’s a totally different vibe to roll up to a spot with the intention of jumping off a bridge. Needless to say, the sunbathers were dumbfounded that anyone would consider jumping into this narrow drop zone.

We were greeted at the site by Aaron Fleenor, an area local who showed us the takeoff and landing and demonstrated it with precision. From an aesthetic perspective, the spot was spectacular—an old footbridge spanning the Yuba River. From my perspective, it was nerve-racking. The landing approximately 65 feet below was narrow and the river was moving.

As onlookers gathered and river-goers gazed up from their beach blankets, Fleenor and Sims climbed onto the railing and gracefully sprung into the canyon waters below.

Brandon Beck climbs a cliff over Frenchman Lake in Plumas County, photo by Ryan Salm

Brandon Beck climbs a cliff over Frenchman Lake in Plumas County, photo by Ryan Salm

Two days later, I found myself rolling north into Plumas County past cows, farms and large swaths of forest. I couldn’t help but think that cliff jumping sure takes you to some beautiful landscapes. The sun was sinking toward the horizon and I was racing to meet Beck and Alex Shirley for a sunset session.

Before long the three of us, along with Lane and Beck’s girlfriend, Sydney Lloyd, were standing atop a spectacular cliff band of lichen-covered volcanic rock on Frenchman Lake. The rocks shone with an amber hue as the sun mixed with the yellows and oranges.

The wind was blowing, casting texture on the water’s surface. Both Shirley and Beck agreed that texture is much preferred over glassy water, as it helps to gauge the distance. With confidence on their side, Beck and Shirley proceeded to launch from various heights in the waning sunlight.

Cliff jumpers are calculated in their craft. Here, Alex Shirley measures the distance from launch point to water during an evening session on Frenchman Lake, photo by Ryan Salm

Cliff jumpers are calculated in their craft. Here, Alex Shirley measures the distance from launch point to water during an evening session on Frenchman Lake, photo by Ryan Salm

Staying Safe

It’s easy to look at these guys and their videos, click “Like” and then say they’re nuts. After observing them in their element, however, it’s clear that what they do is calculated. They take the necessary precautions to keep themselves safe and alive. Yet even the most skilled jumpers are susceptible to injury.

“I know of a few broken backs, big hematomas, collapsed lungs and other injuries,” Wilson says.

Wilson has had one accident. He was jumping 65 feet into a shadowy landing. When he jumped out, his body moved into an area of glaring sunlight. He planned to throw a double front flip 180, but the sunlight blinded him. He lost sight of his landing, opted to tuck into a ball, over-rotated and landed on his back.

“People are gonna make mistakes. That is the risk of this game,” he says.

To lessen the impact from such great distances—a person jumping from 90 feet will hit the water at more than 50 miles per hour—cliff jumpers often seek out waterfalls. This is because the falling water breaks up the surface tension, making the impact less abrupt. In their recent documentary, Flow State, Beck, Nick Coulter and others can be seen jumping off waterfalls.

“Low surface tension and less dense water means you can jump from higher,” Wilson explains. “Any water that is aerated will have less density and typically will have more air bubbles; that’s what makes waterfalls so good. As long as you know that the aeration in the water won’t put you all the way through the water and into the rocks below.”

For these athletes, it’s not a simple process of walking up to a cliff, looking over the edge and jumping into the arms of fate. There is a process. When they come to a new jump site, they often swim with masks and snorkels and gauge the landing sites. Beck, who comes from a legacy of extreme athletes—including his dad Greg Beck, who aired 117 feet off the nose of Squaw Valley’s Palisades in 1975—has been jumping off cliffs since he was 13.

Every spot we went, there was one thing in common between everyone who jumped: the rocks. Before anyone jumped, they stood at the edge with about three rocks, which were tossed one at a time into the water below to judge hang time and trajectory. Also part of the pre-jump routine, most take the time to go over the tricks in their heads in an attempt to visualize themselves doing it.

Alex Shirley executes a gainer with precision over Frenchman Lake, photo by Ryan Salm

Alex Shirley executes a gainer with precision over Frenchman Lake, photo by Ryan Salm

On our trip to Frenchman Lake, Shirley seemed reluctant to jump. After a conversation he opened up and spoke about a recent mishap. A week prior, he was overconfident on a jump, bypassed his normal ritual and took a 75-footer to the ribs. The result—immediate pain followed by days of coughing up blood, difficulty breathing and a small case of second-guessing himself. He was a bit rattled and needed to get back into his groove again.

After carefully examining the jump and going through his routine—even pulling out a tape measure to pinpoint the distance—Shirley executed a giant gainer to perfection, restoring his confidence.

Cliff jumping has never been more popular in its 250-year history. Crews are springing up nationwide, while viral videos, YouTube channels and even feature-length documentaries are readily available for public consumption. East versus West cliff jumping extravaganzas are in the making as what was once a daredevil activity has now morphed into a full-fledged sport.

So if you find yourself in proximity to high perches above water, don’t be surprised if an aerial showcase ensues.

Ryan Salm is a Tahoe City–based photographer and writer.

Eric Lamberts

Posted at 08:35h, 27 JuneNo mention of Angora lakes?